Lessons for the anti-Trump resistance from American history

As progressives search for the next step in a world where Republicans will control the White House, both chambers of Congress and the majority of statehouses and governor’s mansions, the nascent anti-Trump resistance movement has been doing civil disobedience outside Trump Tower, pushing for bipartisan congressional investigations into Russian election meddling and itching to expose his Cabinet nominees’ conflicts of interest with the hope of sinking one — or perhaps even two or three — of them. Green Party-led recount pushes in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin drew national attention but in the end had little impact, other than to recertify Trump’s win, and Democratic efforts to urge Republican electors to vote their conscience, not their party, similarly sputtered.

Still, the liberal resistance to Trumpism has only started to gear up for what will probably be a series of epic battles around touchstone issues of race, immigration, health care and authoritarianism itself. Trump is weighted down by a 43 percent approval rating, making him the least popular newly elected president in the past half century. As the liberal-left works to organize in this environment, it confronts a set of opportunities, as well as tough questions about the path forward: Who should be the leaders of this resistance? Which strategies and tactics should they employ? What organizations and institutions could prove to be the savviest and most influential in curbing Trump’s authoritarian tendencies?

The answers will have implications not just for politics but also for the entire country during the coming Trump era. And the paths forward are in part illustrated by America’s rich history of political resistance on the left and the right — a legacy that’s both fraught and inspiring, filled with blinking yellow lights and solid-green guideposts. The resistance leaders will have at least four modes of viable dissent as they seek to launch a robust movement that can block some of the most feared aspects of Trump’s agenda.

Direct action. Though conservatives typically decry antiwar and other street demonstrations as emblems of a time defined by left-wing excesses that contravened political norms and moral behavior, the nonviolent mass protests of the 1960s, 1970s and even 1980s offer clues to potent models of political and cultural dissent. Nonviolent marches helped pressure elected leaders to overturn segregation in the South and expand legal rights and social protections for women. Anti-Vietnam War demonstrations made it harder for policymakers to prosecute the war with the free hand they sought. President Ronald Reagan’s refusal to recognize the threat of HIV/AIDS as a public health crisis provoked mass protests, which pricked the country’s conscience and ultimately led to more funding for research and better treatments.

Trump continues to court ideas that could trigger a new wave of mass nonviolent protests. Asked for his reaction to the terrorist truck attack in Berlin last week, Trump told reporters that he has been “proven to be right” yet again, implying that his suspicion of Muslims was, essentially, justified all along. If Trump ultimately followed through with his campaign pledge to bar Muslims from entering the United States, if he opted to create a government registry to track Muslim-Americans in the United States, nonviolent protests could easily erupt. Policies that are widely seen as assaulting civil liberties and infringing on civil rights would probably trigger demonstrations that could hinder Trump’s agenda and consume his presidency. The women’s march the day after the inauguration could be just the start.

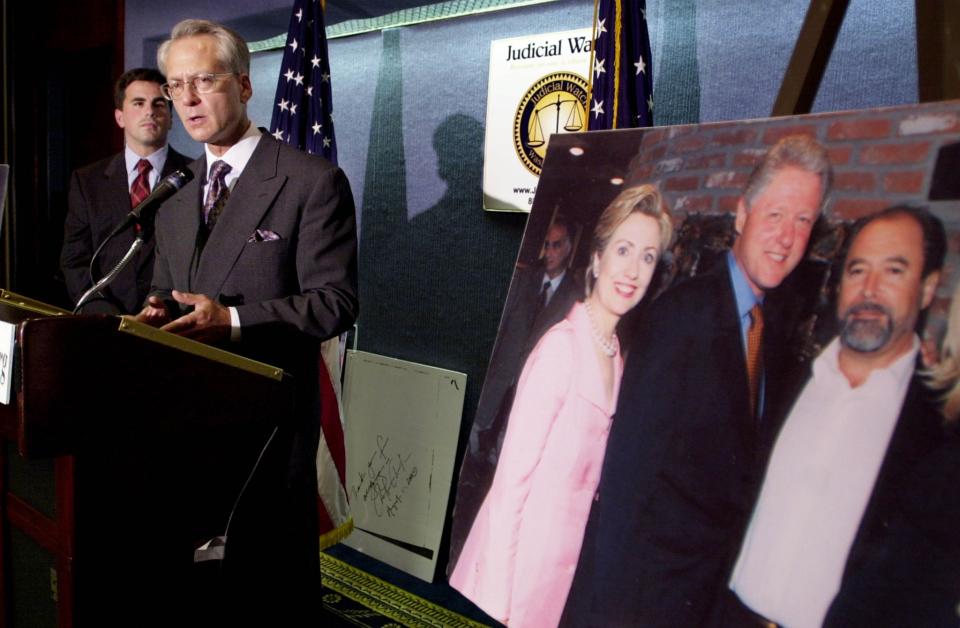

Lawsuits. Democrats and progressives can also take some solace in Larry Klayman’s use of lawsuits to inflict political damage on President Bill Clinton’s administration. Klayman led the well-funded right-wing Judicial Watch organization during the 1990s. Armed with a stable of lawyers and a bald partisan agenda, Judicial Watch filed more than 18 lawsuits against members of the administration.

Klayman forced Clinton aides to sit for depositions, forced the release of documents, generated news stories that depicted the Clintons in an unflattering light and tarred the administration with a taint of scandal. Although progressives lack an obvious candidate who can become Trump’s Klayman, they can take a page from Klayman’s strategy of using the courts as a tool that can paint Trump as a president with dubious ties to Russia, business interests around the world and a questionable commitment to constitutional principles.

Legislative obstruction. During Barack Obama’s presidency, Mitch McConnell’s stated goal was to make him a one-term president. By opposing virtually every major legislative item or executive initiative undertaken by Obama, McConnell adopted a “just say no” approach to resisting a White House at odds with his ideology.

Ten Democrats are facing reelection in red states won by Trump, and some of them will surely want to show that they are siding with a president who is popular in their home states. McConnell’s strategy is going to be hard for Democrats to ape.

But if incoming Minority Leader Chuck Schumer can’t count on his own party on every issue, he can seek to peel off votes on key issues from a handful of Republicans who remain skeptical of Trump’s agenda. On some of Trump’s more extreme plans and nominations — David Friedman as ambassador to Israel, for instance — congressional Democrats can unite around a single message, galvanizing partisans in hopes of achieving the occasional legislative victory. And with the GOP fractured by those who view Trump as a con artist scornful of conservative principles, Democrats may win support from senators such as John McCain, Jeff Flake or Marco Rubio on an issue like Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

Electoral mobilization. Lastly, progressives have a usable model in the right-wing tea party. Birthed in reaction to Obama’s first-term policies and bent on toppling Republicans who dared to negotiate with the president on almost any matter, the tea party succeeded in unseating House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Speaker John Boehner — and, most relevant to the anti-Trump movement, it energized conservatives around the electoral process. A tea party movement of the liberal-left, whatever form it ultimately takes, could inject a dose of momentum to a dispirited party and mobilize Trump’s foes to take their country back.

There are risks aplenty facing any anti-Trump resistance. One is that factions will emerge that mar any effort at unity, giving way to a sectarian, scattershot effort that scorns electoral politics and puts expressive protest ahead of strategic action.

The warning lights include the experience of Occupy Wall Street, the short-lived movement that protested the excesses of America’s financial titans. The movement never settled on a clear set of goals or a legislative or political strategy that could prove successful and sustain the change-making efforts. Artistic and propagandistic efforts, such as filmmaker Michael Moore’s 2004 “Fahrenheit 9/11” documentary, have other risks, even as they can gain widespread notice and acclaim. That movie at times dabbled in conspiracy theories and did not move opinion on George W. Bush enough to keep him — an incumbent wartime president working with a team of sophisticated electoral strategists — from winning a second term.

Other resistance efforts proved more destructive. During the late 1960s and early ’70s, the Weather Underground, a radical offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society, used violence in a vain, repellant attempt to topple the nation’s governing institutions.

But these are detours from the usable pathways for forging a cohesive resistance to Trump-era politics and policies: traditions left and right of mass mobilization and elite legal strategies, electoral politics and congressional tactics. In taking these known avenues, dissenters might just defy their reputation as soft and ineffectual — and stop some of their worst nightmares from being realized.

_____

Matthew Dallek, associate professor at George Washington’s Graduate School of Political Management, is author of Defenseless Under the Night: The Roosevelt Years and the Origins of Homeland Security.