For the love of the brain: One mother's fight for CTE awareness

Produced by Samantha Feltus and Gaby Levesque

Karen Kinzle Zegel spends her days working on the Patrick Risha CTE Awareness Foundation website, fielding questions and giving out information on a disease she barely knew existed five years ago – until it took the life of her son, for whom the foundation is named. She and her husband Doug Zegel, Patrick’s stepfather, share their story of losing him to suicide to everyone they meet.

“We didn’t choose this, it chose us,” Doug tells Yahoo News.

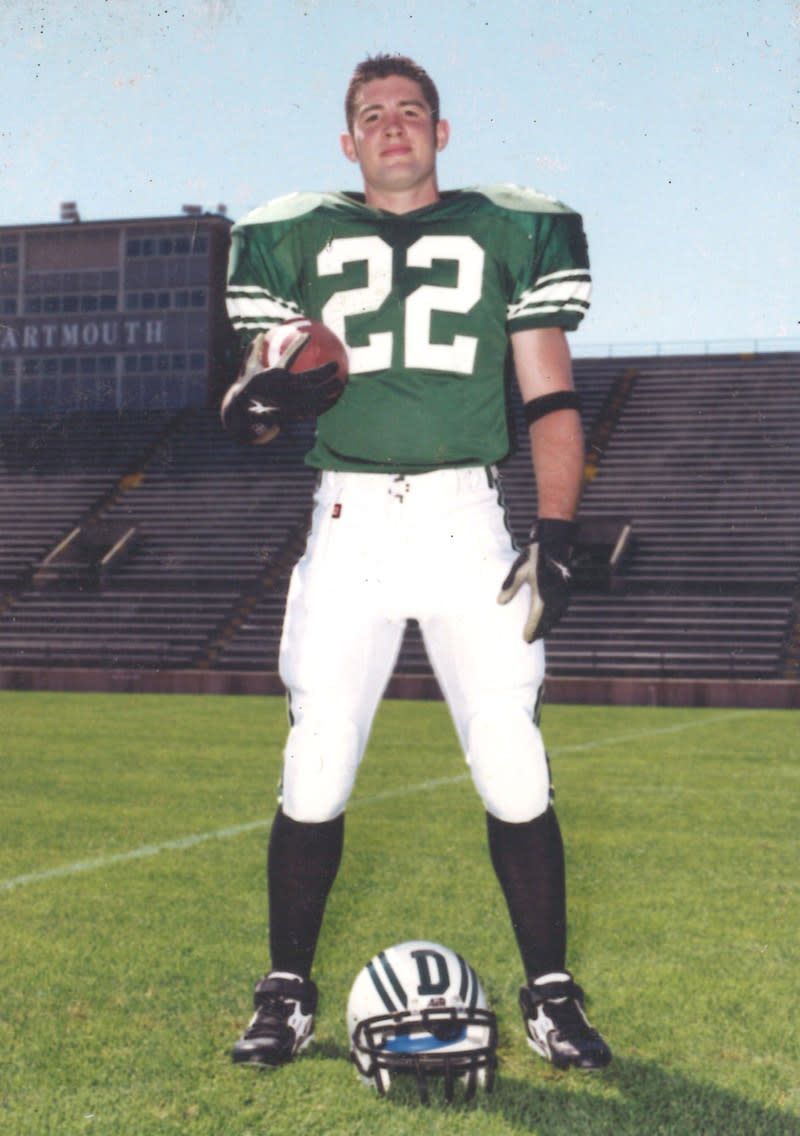

By all accounts, Patrick Risha had a typical middle-class suburban upbringing in Pennsylvania. He was a protective big brother to his sister Amanda, enjoyed being the funny man of the family, and loved to play sports, especially football. He played the game as a child, into high school and was a running back during his time at Dartmouth College.

Karen remembers, “We were a football family, his dad was a coach, I would cheer and yell and you know, do all the things the football mom does. I was really into it. But there was always that fear that maybe there would be something orthopedic or maybe he could get paralyzed, and that would scare me. But I never dreamed it could be a brain injury.”

In the years leading up to Patrick’s suicide in 2014, Karen tried everything she could to help her son cope with debilitating mental and emotional distress. At the time, she was unaware of CTE – chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head – and the role it was playing in Patrick’s life. His bouts of anger, confusion and frustration puzzled the family, and his struggle with drugs and alcohol further exacerbated his instability.

Randi Patterson, the mother of Patrick’s son, Peyton, recalls: “The best thing about Patrick was that he always made sure I was OK, no matter what. … But as the disease progressed, he couldn’t play with him [Peyton]. He really couldn’t do anything at all with him. So it was sad to watch, and again, not knowing that it was a disease, I thought it was a choice that he made to just not want to be there.”

It wasn’t until after Patrick’s suicide that the family learned he had been suffering from CTE. A family friend had suggested it as the cause of Patrick’s symptoms, but it can only be diagnosed by examining the brain after death. Currently, there is no test to identify the disease in the living.

“I would not know about CTE if it weren’t for Ann McKee,” Karen tells Yahoo News. Dr. Ann McKee is the chief of neuropathology at the Boston VA and the director of the CTE Center at Boston University. She has dedicated her career to develop treatments and, ultimately, a cure.

“CTE is triggered by repetitive brain trauma. That can be repetitive impacts like concussions and subconcussive hits. Once it’s started, once it’s triggered and it’s taken hold in your brain, it’s going to get gradually worse the longer you live.” says McKee.

The majority of hits to the head experienced by athletes in sports like football, soccer and ice hockey usually affect the frontal lobe. This area of the brain controls functions including impulse control, decision making and emotion regulation. “Things like depression become worse with frontal lesions,” says McKee.

The correlation between CTE and its potential to increase the risk of suicide still needs further research. Dr. McKee explains, “There’s so many factors that go into suicide that have nothing to do with CTE. But is it more likely that you’re suicidal if you have CTE? Our suspicion is that’s true.” She notes that there is evidence that even mild trauma like concussion increases the risk of suicide.

“Trying to get through that we need to act on this now so we lessen the problem, so we take care of our athletes as they’re growing up,” is one of the biggest obstacles McKee says she and her team face in finding a cure.

Taking care of his players and ensuring they will have success beyond their athletic careers is a top priority for Dartmouth’s head football coach, Buddy Teevens. In 2005, Teevens returned to Dartmouth as head coach after Patrick was no longer playing for the team. Their paths never crossed and Teevens never had the opportunity to coach Risha. As alarm grew about CTE among NFL players, Teevens spoke with the St. Louis Ram’s then-coach, Jeff Fisher, during the team’s practice. Teevens asked what the Rams were doing to make practice safer, and learned the team didn’t do tackle drills, ever. Fisher explained, “Too many guys get hurt.”

Teevens returned to Dartmouth and announced to his staff that tackling would no longer be allowed during practice. While the response was anything but enthusiastic, the decision had been made. Tackling pads and dummies proved to be helpful, but Teevens was frustrated by his inability to replicate a moving target for his players. He reached out to John Currier at Dartmouth’s graduate school of engineering to see what could be done. With the collaboration of engineering students at the school the Mobile Virtual Player (MVP) was created, the first of its kind.

The proof was in the results, as injuries declined and missed tackles decreased by 50 percent. Teevens says, “If I’d stopped tackling and we went 0 and 10, you wouldn’t be talking to me right now. [But] we stopped tackling and we had success.” In 2016, Teevens inspired Ivy League coaches to eliminate full-contact hitting in practice. Dartmouth went on to multiple wins, including ending a 14-year losing streak against Harvard in 2018.

When asked about Karen Kinzle Zegel and her mission to educate the public about the risks of CTE, Teevens was supportive, “You have people like Karen that are willing to give of their time and support research, tell their personal story. That impacts me as well.”

Encouraging the prevention of CTE, along with supporting research to find a cure, is what Karen and her family hope to accomplish. Today, Jan. 30, is CTE Awareness Day. Karen shares on her website, “This is a day to reflect on those lost to CTE, how to help those suffering with the disease, and most important, how to stop the disease.”

Karen says, “I still have friends that let their kids play hockey and let their kids play football and they share it on Facebook as well. And I go, ‘What am I missing?’ So, we still have work to do.”