The Main Character

From the Boiling Frogs on The Dispatch

This must be the first presidential campaign in which both candidates have the same strategy.

For one it’s a matter of deliberation and for the other it’s a symptom of narcissism, but they end up in the same place: Each wants the race to be a referendum on Donald Trump.

Trump’s advisers surely would prefer to make it a referendum on Joe Biden. The president has a job approval of 40.3 percent, an age problem that gets worse every day, and an albatross in the form of persistent inflation that he can’t shed. All Republicans need to do to win is clam up, lie low, and let political gravity do what political gravity does.

But that would require personal discipline from their nominee. And, well, you know.

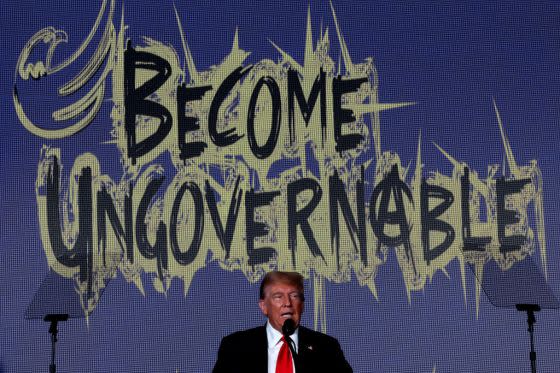

In the last week alone, Trump has attacked the Hispanic judge in his criminal trial by calling attention to “where he comes from”; appeared onstage at a rally with two men charged with conspiracy to commit murder; seemed to discourage Russia from freeing Evan Gershkovich, the imprisoned Wall Street Journal reporter, unless and until he’s reelected; and celebrated Memorial Day by blaming his troubles on “the Human Scum that is working so hard to destroy our Once Great Country.”

Meanwhile, his effort to convince Americans that the election will be illegitimate if he loses is way, way ahead of the pace he set in the 2016 and 2020 cycles. To reassure wary swing voters, he should be doing everything he can to demonstrate that he’s no longer the maniac they remember from his final weeks in office. Instead, he’s done the opposite.

All of this is both exactly what the Biden campaign expected and hoped would happen when Trump became the Republican nominee. The president can’t win an election in which the core question is “Are you happy with Joe Biden’s first term?” But he might be able to win an election in which the core question is “Do you really want to see what a coup-plotting lunatic does for an encore?”

That explains why Biden agreed to a surprisingly early debate with Trump next month. It also explains the spectacle outside the courthouse in lower Manhattan on Tuesday morning in which Robert De Niro and a few of the hero cops from January 6 showed up to address the swarm of media on Team Biden’s behalf. Democrats are desperate for ways to call voters’ attention to Trump’s deviancy—and Trump himself, bless his heart, is doing everything he can to accommodate them.

And … Trump’s still winning anyway. In fact, he hasn’t trailed in the RealClearPolitics national polling average for so much as a day since early September of last year.

Liberals are coping with this by vacillating between panicking that Biden’s weaknesses are insurmountable and sweaty self-persuasion that the public will eventually reawaken to Trump’s insanity. “Voters do not realize, or have not fully grappled with the reality, that Trump will be on the ballot in November,” New York Times reporter Jason Zengerle wrote on Tuesday, summarizing the White House’s view. “Once they do, the Biden team appears convinced, they’ll remember all the reasons they sent Trump packing four years ago.”

I’m less convinced than they are that this election will ever be “about” Trump enough for voters to rescue Biden. As much as both candidates want him to be the main character in the story of 2024, that story will be a hard one for Democrats to tell.

One answer to the question of why Trump’s unfitness doesn’t matter to voters is that it does matter. Just not enough.

In the history of Gallup polling, no president has had a worse approval rating at this stage of his first term than Biden has. The second-worst belonged to George H.W. Bush, who still managed to crack 40 percent during the 1992 recession en route to a resounding defeat that fall. Biden averaged just 38.7 percent in the last quarter by comparison, which should make him unelectable.

But he isn’t. Because his opponent is grossly unfit for office, the president trails in national polling by only a point or so and is running nearly 6 full points ahead of his job approval. In the three Rust Belt battleground states that can guarantee his reelection, he’s behind by only 2.3 points or less. Public anxiety about giving Trump a second chance is single-handedly keeping Democrats in the game. A more generic Republican nominee would probably be waltzing to victory.

A guilty verdict this week in Trump’s criminal trial might help Biden fans sleep easier at night, as might next month’s debate if the president performs well (unlikely) or Trump behaves obnoxiously (inevitable). Biden and his party can find cause for hope in that.

But it feels strange and ungood that we’re five months out from a Trump restoration and still debating when (and whether) a critical mass of Americans will feel alarmed enough about it to hand the incumbent a lead in the polls.

One uncomfortable possible answer: Never. Biden might never be able to reach the voters he needs to make up the difference between him and Trump.

If you’d told someone 20 years ago that the internet would make it harder for politicians to reach persuadable voters, they’d have given you the same confused head tilt that a dog does when you hide its toy. Digital communication is all but costless, and new platforms arise every day, so modern candidates have many more “lanes” they can travel to deliver information to the average undecided voter. That should make it easier.

It doesn’t. The problem, as we’re frequently reminded in this newsletter, is that having more “lanes” means news consumers can be more selective about the information they allow through while still making a pretense of being informed. That’s how we ended up last week with populists hyperventilating about an FBI assassination plot against Trump. They can block off every lane to the left of Fox and still not want for, ahem, “news.”

An undecided voter won’t have the same information filter as a MAGA fanatic, of course, but they will have filters. Some will end up blocking off “lanes” having to do with the election out of sheer disgust with their choices this year. And insofar as either candidate does manage to puncture their bubble, a candidate like Trump with an enthusiastic fan base might have more success than an enervated alternative like the Biden operation will.

Another barrier for the White House in moving undecided voters is the nature of Trump’s candidacy. He’s not just a party nominee, he’s a former president. Voters observed him closely for four years and arrived at a judgment about him before the last election. Nothing that he’s said or done since then has given them a reason to change their opinion about him: For Trump boosters and Trump haters alike, the craziness is baked in. Even his boorish Memorial Day greeting is par for the course by now.

He had his reckoning with voters four years ago. Biden hasn’t had that same reckoning yet, which is why he’s probably destined to be the main character in this election despite his and Trump’s best efforts to make it about the Republican. Skim Gallup’s data on public opinion about the two candidates’ respective presidential qualities and you’ll find that views of Trump have barely budged since 2020. All of the movement in the numbers comes from declining esteem for Biden’s capabilities.

Maybe it just isn’t possible for an incumbent to make his reelection bid a referendum on his opponent rather than on himself, especially when that opponent is someone about whom every American voter formed an unshakeable opinion long ago.

That would explain why the media isn’t covering Trump’s daily bursts of civic depravity as page-one news the way some of his critics would like. It’s not just a matter of the country being broadly and shamefully desensitized to it by now (although it is partly that). It’s a matter of it arguably not qualifying as “news” insofar as it no longer moves opinion at all. How many voters out there are willing to let Trump slide on a coup plot but draw the line at him tweeting about “human scum” on Memorial Day?

It might even be the case that Trump seems less radical to swing voters than he did four years ago despite the considerable news coverage of his illiberal designs for a second term. Political consultant Sarah Longwell speculated on a Bulwark podcast last week that Trump might be benefiting from a contrast with fringy Republican candidates down-ballot like Mark Robinson and Royce White insofar as his moderate positions on certain cultural issues make him seem “reasonable” by comparison. The MAGA-dominated GOP is now so wacky in some of its attitudes relative to its nominee, in other words, that that wackiness might be inadvertently insulating Trump from Democratic attacks that he’s some special threat to the constitutional order.

If that’s true, Biden’s going to have an even harder time convincing voters that he’s clearly the lesser of two evils in this election.

But even if he solved that problem and the others I’ve mentioned, there’s a structural problem lurking. Namely, the voters who look poised to decide the election might not be reachable by anyone.

A few days ago, Nate Cohn flagged an important finding in the New York Times’ polling on the election. Among Americans who voted in 2020, Biden still leads Trump by 2 points. That’s down a bit from his 5-point margin of victory four years ago, but only a little.

The sea change has come among those who didn’t vote in 2020 but might vote in 2024. Trump leads that cohort by no less than … 14 points. They’re the difference between victory and defeat.

Those “disengaged voters” aren’t white rural conservatives whom you might expect to prefer Republicans, either. Per Cohn, “these disengaged low-turnout voters are often from predominantly Democratic constituencies” like young adults and nonwhites. And winning them back will be more complicated for the White House than babbling on about traditional liberal causes like “canceling” student loans or raising the minimum wage:

Less engaged Democratic-leaning voters have distinct political views, and they get their political information from different sources. Even if the Biden campaign can reach these voters, it is not a given that they will return to the Democratic fold.

In the battleground states, Democratic-leaning irregular voters are far less likely to identify as liberal. They’re much less likely to say abortion and democracy are the most important issues, and instead they’re far likelier to cite the economy. They overwhelmingly say the economy is “poor” or “only fair,” even if they’re still loyal to Mr. Biden, while a majority of high-turnout Democratic-leaning voters say the economy is “good” or “excellent.”

By definition, disengaged voters are harder to reach than engaged voters because they don’t pay as much attention to politics. And to the extent that they are paying attention, Cohn points out that these voters tend to get more of their “news” from social media than most Democratic-leaning voters do. Here again, Team Biden will need to somehow puncture the information bubble that disengaged voters have created for themselves and will need to do so more effectively than the Trump campaign will.

You can understand why the campaign enlisted a celebrity like De Niro for its messaging purposes on Tuesday, then, and why it chose to have him speak outside the courthouse where Trump is being tried. It’s desperate for ways to reach disengaged voters and celebrities are more likely to do that than politicians are. Ditto for the coming verdict: If Trump is found guilty, that headline will make its way to people who normally avoid political news.

Let’s assume that the campaign’s message successfully reaches them, though. How do they get those voters to care?

The most striking detail from Cohn’s analysis is that disengaged voters prioritize the economy more than most Democrats do, and they’re relentlessly gloomy about it—which makes sense. Younger and nonwhite voters are less likely to be wealthy, so they’re apt to have felt the bite from inflation more acutely than higher-earning liberals have. You can picture them staring at this chart while the president lectures them about democracy and abortion and his words slowly morph into the gibberish spoken by Charlie Brown’s teacher.

Perhaps that’s why Biden is inescapably the main character in this election. When inflation is at a 40-year high, too many Americans don’t have the luxury of making the campaign “about” anything else. “If the frame of this race is, ‘What was better, the 3.5 years under Biden or four years under Trump,’ we lose that every day of the week and twice on Sunday,” one Democratic strategist told Politico.

Which raises a new dilemma for the president and his party. If they do figure out a way to reach disengaged Democratic voters, might they be better off letting sleeping dogs lie?

Imagine if they invest $200 million into a robust turnout effort designed to get low-propensity young and nonwhite voters to the polls on Election Day. Maybe those voters will be swayed by Biden’s outreach and vote for him—or maybe they’ll vote for Trump, as many are currently inclined to do, aborting their plans to skip the election this year after Democrats made it easy for them to register and get to the polls.

If that happened, a left-wing get-out-the-vote effort will have inadvertently delivered a second term to a man whom Democrats impeached. Twice.

That Catch-22 will haunt Biden for the rest of the campaign, I think. Every time his team figures out a way to raise awareness about the election among disengaged voters, they’ll be left to wonder if they’re doing themselves more harm than good. If the election is “about” inflation and there’s no way plausibly to make it about anything else, Democrats should want low turnout in November. The less interest in voting among the public, the better off they are.

The bottom line is that Trump could end up winning reelection with one of the strangest coalitions in American political history. His movement is driven by rabid right-wing cultists who are prepared to tolerate all manner of dubious power grabs in the name of crushing the left. Yet the bloc that’s poised to put him over the top is a group of traditionally Democratic working-class voters who care mainly about getting prices under control.

Fanatic ideologues and kitchen-table pragmatists: He’s the candidate of disaffection in all its forms, and he’ll take full advantage. A dark part of me thinks it would be funny if young, left-leaning voters crossed over to support him in the belief that he’ll solve inflation and ended up getting a lot more than they bargained for.

As for pundits’ hand-wringing that Team Biden should be doing more to make Trump the main character in the race, it feels to me like cope.

It’s comforting to believe that, on some level, Americans still don’t know who Trump truly is rather than that they’re prepared to choose him knowingly and willingly. There are a lot of ignoramuses out there, admittedly, but we’re less than four years removed from a coup attempt he orchestrated that played out in full public view. To blame Trump’s strong polling on a failure of “messaging” by Democrats is to ask why, at this point, voters in a supposedly respectable country need the arguments against him “messaged” in the first place.

The fact that Biden is unpopular is no answer. If the president had opted against running for election and Democrats had nominated Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer instead, say, what do we think the polls would look like right now? Whitmer by 3 maybe? “This isn’t, ‘Oh my God, Mitt Romney might become president.’ It’s ‘Oh my God, the democracy might end,’” one Democratic operative said to Politico about panic on the left over Biden’s weakness. But, realistically, there’s no nominee the party might have chosen who would have enjoyed an easy victory over Trump.

Roughly half the country simply has no real problem with anything Trump has done and will support him over any Democrat, no matter how young and centrist that person might be. The only good thing about Trump winning this fall will be that it forces Americans who have lived in denial until now to confront what their country has become.