Nationwide sweep to rename schools that honor Confederate leaders reveals some districts' racist pasts

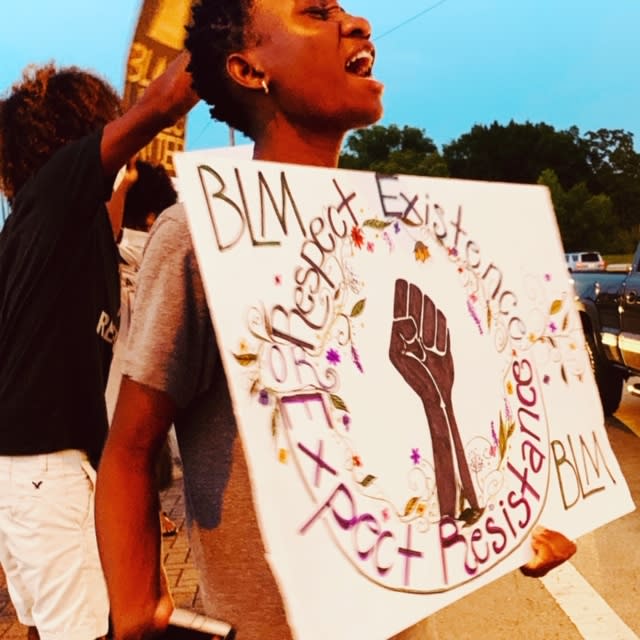

Rising pressure from students, community members and the national Black Lives Matters movement is pushing school boards across the country to rename schools that honor Confederate soldiers and slave owners. There have been efforts for years to remove Confederate names from schools, but the death of George Floyd may be a tipping point.

“After the murder lynching of George Floyd, people seemed to put together for themselves what were the symbols or underpinnings or infrastructure of white supremacy,” says Lecia Brooks, chief of staff at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The Southern Poverty Law Center has compiled a census of Confederate symbols in public spaces across America and estimates that there are 103 public K-12 schools and three colleges named for the Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis and other Confederate icons.

Brooks says school name changes have happened more quickly since 2016, when the SPLC released its initial report following the Charleston, S.C., church shooting. Initially, Brooks says, the SPLC identified 147 schools with Confederate names, and 46 have been renamed.

The changes have taken place with greater frequency in Northern states since some Southern states have laws that restrict the renaming of public schools and monuments that named for Confederate leaders.

“I think that there is, in fact, a feeling on the part of some people, many of whom are white, that this is an attempt to ‘erase history’ or that they see it as an attack on Southern heritage,” says Ben Frazier, a civil rights activist in Jacksonville, Florida and founder of the community advocacy organization the Northside Coalition. “It is, in fact, an attack against Confederate heritage. And we do see that there is a definitive difference between the two.”

Brooks points to the Confederate iconography used by white nationalists during the 2017 Charlottesville rally as well as by white gunman Dylann Roof before he shot 9 Black churchgoers in Charleston in 2015.

“It really counters this whole narrative about ‘heritage not hate’ because these Neo-Confederates… always hold on to this Confederate flag as a symbol of white supremacy,” she says.

According to Edweek, most of the schools that honor Confederate leaders are in states below the Mason-Dixon line, which, prior to the Civil War was the dividing line between slave states and free states. It cites seven states with the highest concentration of Confederate-named schools: Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, Texas and Virginia.

But activists are pushing for change.

In Jacksonville, nearly 14,000 people have signed a petition to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School and five other schools in the district named after Confederate leaders.

In Virginia, the Fairfax County Public Schools board has agreed to rename a high school named after Robert. E. Lee, which will go into effect for the 2020 school year.

And in Tyler, Texas, students activists are asking the school board to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School – something they’ve been asking for since 1970, so far to no avail.

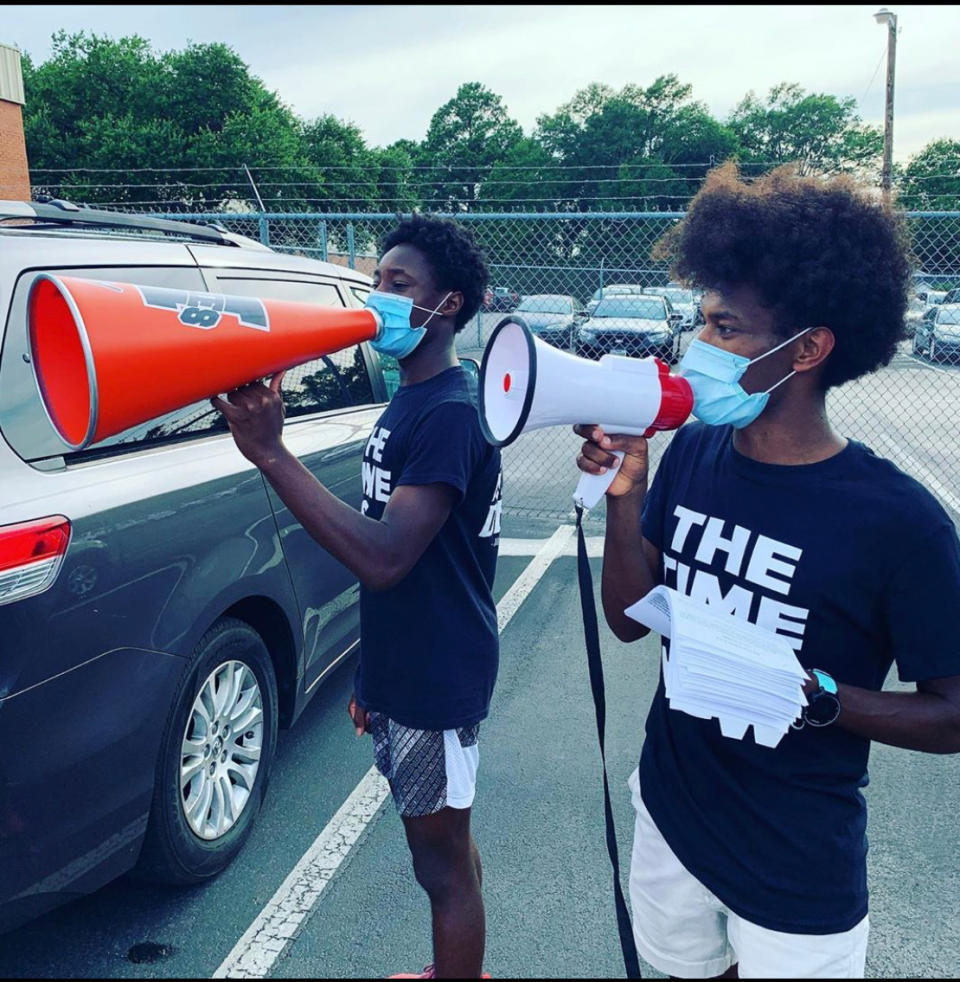

Nigusom Knight, who goes by the name Nick, is a senior at Robert E. Lee High School in Tyler and a co-leader in a student-led protest to change the name of the school – a school that he says is 78 percent Black, Asian and Hispanic.

“The death of George Floyd kind of sparked a whole protest around the whole country,” he says. “Seeing how Black people were really being treated, I think that influenced a lot of people to say, ‘Wow, we definitely need to change.’”

An incoming sophomore at Robert E. Lee High School, Trude Lamb made national headlines in June after writing a powerful letter to the school board telling them she would no longer wear the school’s cross country jersey, which has the name “Lee” written across the chest. She also takes issue with the school song, which glorifies the Confederate general: “Robert E. Lee, we raise our voice in praise of your name. May honor and glory e'er guide you to fame.”

“I want the name of the school to change because I don't want to be going to a school named after a person who was a slave owner and they didn’t want Black people to have rights,” she told Yahoo Life.

Students attempted to change the name in 2017 as well. In the wake of the August 2017 white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., students asked the school board to change the name of the high school. But the board declined to vote to change the name. The issue was abandoned until it was raised again this year, in the wake of the death of George Floyd.

This time around, students are optimistic that they will win.

More than 15,000 people have signed a petition to change the name of their high school. The board meets to discuss the issue on July 20. If the measure passes, it would mark almost exactly 50 years since July 1970, when Black residents first requested that the school board rename the high school.

Wade Washmon, the Tyler Independent School District Board of Trustees president, did not respond to Yahoo Life’s requests for comment.

Lee Hancock, a former investigative journalist for the Dallas Morning News, conducted extensive research into the racial history of Tyler, Texas, using historical archives, newspapers and public records, to piece together the town’s decades-long resistance to desegregation as well as the history of the naming of Robert E. Lee High School.

Her timeline chronicles a history of Tyler as a segregation battlefield. In 1954, when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools were unconstitutional, the Tyler Independent School District fought all attempts by the federal government to desegregate its schools. The town was at the center of legal battles taking place statewide to combat desegregation as well as to dismantle the NAACP in Texas.

In 1957, the Seventh Judicial District Court in Smith County, Texas, ruled that the NAACP could no longer engage in legal or political activities in Texas. That same year, the Tyler school board voted in favor of naming its new white high school after Robert E. Lee.

“It was only months after that case happened … that the school board voted to choose that name,” Hancock tells Yahoo Life. “And to many in the Black community, it seemed like a ... thumb in their eye. A victory lap, if you will.”

Brooks says naming schools and erecting monuments in honor of Confederate leaders was a common practice in the ‘50s and ‘60s in response to the civil rights movement.

“The two spikes in the creation of these monuments and statues happen to coincide with Blacks pushing for civil and human rights during the fifties and sixties and then prior to that, post-reconstruction when the same kind of thing [was happening,]” she says.

Tyler’s school district wasn’t declared to be integrated until 1972.

It’s worth noting that, Longview, Texas, 40 miles west of Tyler, wasn't declared officially integrated until 2018.

And students in Tyler say the shadows of that racial tension and even outright racism still exist today. Lamb and Knight, who are both Black, say that they have encountered racism by students and even faculty. They are asking for an outside consultant to assess the school and work with teachers and faculty on antibias training.

“The name of the school, like the history behind why it was named [Robert E. Lee] and just Tyler as a whole has a very racist history. So we’re trying to change that because it is still very much intact today,” says Knight.

In Jacksonville, Fla., the school board of Duval County Public Schools voted to consider changing the names of six schools named after Confederate leaders: Joseph Finegan Elementary, Stonewall Jackson Elementary, Jefferson Davis Middle School, Kirby-Smith Middle School, J.E.B. Stuart Middle School and Robert E. Lee High School.

Warren Jones, chairman of the Duval County school board, says the schools were named in the 1920s and the 1950s, four of which he told Yahoo Life, “were named in the ’50s after the Brown decision in 1954. So in all cases, they were direct ... retaliation.”

He says that all six of the schools were built while the school district was segregated, intended for white students only. But today, he says five of the six schools are comprised mostly of minority students.

Even now, Jones says those against renaming the schools are mostly students who graduated from Jacksonville schools in the ’60s.

At a school board meeting on Tuesday, Jones says he and fellow school board members read 70 emails addressing the name change — most of them opposing it. “In Jacksonville, Fla., schools did not integrate until 1971. So all students who graduated prior to 1971 graduated from a segregated school district,” he said.

Frazier, who also grew up in Jacksonville and says he remembers segregated bathrooms and water fountains, says it’s time to rename the schools because of what they represent: “People who fought to maintain and perpetuate that peculiar institution called slavery,” he said.

There is still an extensive process that needs to take place before the names can be changed in Jacksonville. Now that the school board has voted to consider changing the names, the superintendent must come up with a process to gather feedback from the community. The school advisory board will weigh in and then make a recommendation to the school’s superintendent. She will then submit a recommendation to the school board, which will cast the final vote.

Tracy Pierce, a Duval County Public Schools spokeswoman, said the superintendent has yet to come up with a process and there is no timeline for when the next vote will be.

Jones said he’s hopeful the name changes will be made before the end of the next school year. “I’m sure the principals have been briefed and they will start engaging the community and the process of changing the names after school has started,” he says.

“We think that the Duval County school board should stop beating around the bush and use its authority to do the right thing. The school board president is Black. The school superintendent is Black. We want to continue to push them to stand strong and courageous and bold in terms of their respective leadership, administrations and positions,” says Frazier.

Frazier believes the renewed impetus for the school name changes across the country stem from the protests surrounding the death of George Floyd, but also because of events going back to Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Mo.

“What we're seeing now is a renaissance,” he says. “It is multigenerational, it is multiracial and it is multicultural. What we're seeing now is something that has never happened in the United States. Certainly not to this extent. It is brand new. I suggest to you that what is happening right now is not a moment, but a movement. It is a revolution that is occurring before your very eyes.”

Video produced by Stacy Jackman.

Read more from Yahoo Life

Want daily lifestyle and wellness news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Life’s newsletter.