A man was killed after threatening Biden. It's not just him: Threats are on rise across US

Last week, Abigail Jo Shry, 43, of Alvin, Texas, was arrested by federal agents and charged with threatening to kill the federal judge overseeing the prosecution of former President Donald Trump.

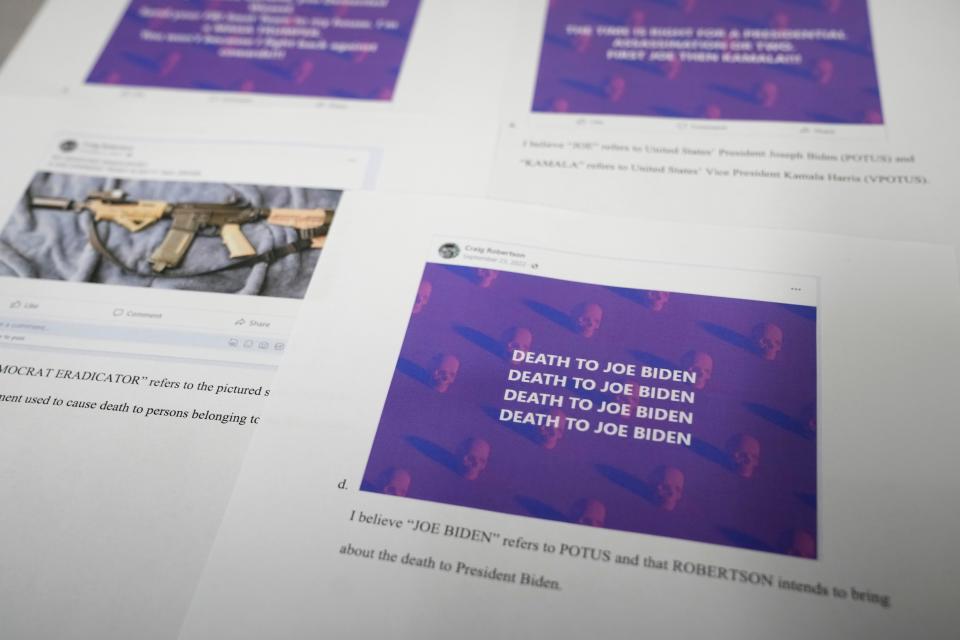

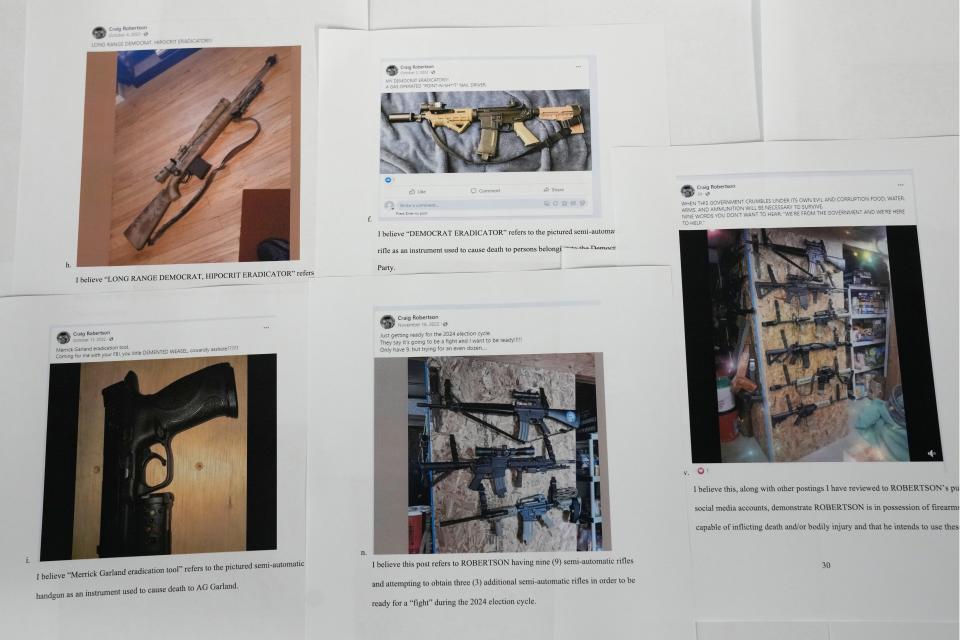

A week earlier, Craig Robertson, 75, of Provo, Utah, was shot and killed by FBI agents who were trying to arrest him on charges of making social media threats against President Joe Biden and the Manhattan district attorney who has brought charges against Trump.

A month before that, Adam Bies, 47, of Mercer, Pennsylvania, pleaded guilty to 14 counts of making threats online against federal officers. Bies was arrested after an armed standoff with FBI agents at his home last August; he faces 10 years in prison.

The flood of news stories about people being arrested, jailed or killed over threats does not come by chance. The number of people being federally prosecuted for threats has skyrocketed in recent years.

Last year, federal officials charged more people over public threats – against elected officials, law enforcement and judicial officials, educators and health care workers – than in any of the previous 10 years, according to research from the National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education Center at the University of Nebraska, Omaha.

This year the trend has continued, said Seamus Hughes, a senior researcher on the team.

“We're on track to meet, if not surpass, the number of federal arrests when it comes to communicating threats against public officials this year,” Hughes said. “Trend lines are going up – violent rhetoric is on the rise, ? and is unfortunately becoming normalized, and that's concerning.”

A year ago this month, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security issued a joint warning about rising threats against law enforcement officials. The warning came days after FBI agents searched Trump’s Florida club and residence, Mar-a-Lago, looking for the classified documents over which Trump has since been indicted.

Trump, who is seeking the GOP nomination to run again in 2024, also faces another federal indictment in Washington, D.C., and local indictments in New York and Georgia. After the Georgia indictment, material circulated on right-wing sites purporting to be photos or home addresses of the grand jurors in the case, along with discussions of threats against them.

In this charged political environment – where a presidential front-runner may also be on trial – experts warn, threatening rhetoric is only likely to increase.

The University of Nebraska data is a snapshot of a broader trend; it captures only prosecutions by the federal government. Many more threats are investigated each year by local law enforcement, and even more are never reported, said Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

“All sorts of agencies have reported increases in threats,” Pitcavage said. “There are a lot of people out there using language to get people angry.”

Once that anger kindles a threat, it can lead to encounters with law enforcement. By that time, no matter whether the original threat seemed realistic, danger often becomes a reality.

From Georgia: Trump may be indicted. But 2020 still casts a shadow over this state's elections

A range of threats

Federal law contains provisions that outlaw threats in various forms: against federal officials or their families, federal employees, federal agencies, witnesses and voters.

The law also broadly prohibits any communication containing a threat if it crosses state or country lines in any way – a scenario that often applies to communication on a phone network or the internet.

Threats, on their own, may not always seem equally likely to lead to violence.

Shry, the Texas woman charged with threatening a federal judge and Sheila Jackson Lee, a U.S. representative from Houston, had been charged locally over earlier threats. In the federal criminal complaint against her, investigators note that they interviewed her at her home and found she “had no plans to travel to Washington DC or Houston to carry out anything she stated.” Yet, agents concluded, Shry without question transmitted an interstate threat.

Other threats rapidly escalate to violence.

When Ricky Shiffer, a man in southern Ohio, opened an account on Truth Social last year, he began posting a litany of far-right extremist conspiracy theories fueled by outrage over the federal search of Mar-a-Lago. Just nine days later, he drove to an FBI office in Cincinnati with a rifle and a nail gun and tried to blast his way in. After a car chase and a standoff, he was shot and killed.

Sometimes, the mere investigation of the threat turns deadly, as it did in Provo, Utah.

Residents told local media they saw Robertson as a harmless older neighbor. But five years earlier, Robertson had confronted utility workers with a gun.

And court documents in the federal case against him show him making detailed threats about execution-style shootings, citing a specific location and weapon. As agents moved in Aug. 9, he was shot and killed; the FBI said an internal investigation is ongoing.

Threats not protected by the First Amendment

People often act under the assumption that their speech is always protected by the First Amendment, Hughes said. But not all speech is protected, and the more specific the threat that is made, the more likely it is for prosecutors to take action, he said.

“For a prosecutor, the ideal case is as direct as humanly possible,” Hughes said. “Someone announces: ‘I will kill someone on this day at this time at this location using this type of weapon.’ That's the ideal situation for a prosecutor.”

Michael German, a former FBI special agent and a fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program at New York University, agreed. At the FBI, German said, he often had to look closely at communications to see whether they constituted a legitimate threat or were protected political speech.

But legitimate threats can’t be ignored, German said. The recipients are victims. They often feel fear and harassment. And it’s incumbent on law enforcement to investigate, because threats can lead to real-life acts of violence, he said.

“There is a pretty stark line between somebody saying something very mean and nasty about what bad things that should happen to you and a true threat,” German said.

Threats increasing

The team at the University of Nebraska tallied how many federal prosecutions have been filed over threats in each year from 2013 to 2022.

Over that decade, the number of such cases almost doubled, from 38 in 2013 to 74 in 2022, the researchers found.

In a new analysis provided exclusively to USA TODAY, the team found 44 such prosecutions this year.

The cases include threats against elected officials and law enforcement but also a few instances of threats against election workers and health care workers, including two cases in which Planned Parenthood was the alleged target.

Hughes noted that the number of prosecutions is increasing not just because more people are making threats but also because the federal government has prioritized cases such as these. In the past, he said, the FBI and the Department of Justice would often pass such cases to local prosecutors rather than bringing them themselves.

‘A dangerous situation’

Pitcavage, Hughes and other experts are quick to point out that not all threats against public officials come from the far right or from Trump supporters.

Just this month, Tracy Marie Fiorenza, of Plainfield, Illinois, was charged by federal prosecutors after allegedly sending emails to the headmaster of a school in Palm Beach, Florida, threatening to kill Trump and his younger son, Barron.

But the majority of the threats being prosecuted by the federal government are coming from the far right, Hughes said.

Rachel Carroll Rivas, deputy director of research, reporting and analysis at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, which has monitored the extreme right and antigovernment groups for decades, said her team has recently observed “a marked increase in the advocacy for violence against public officials, elected officials and candidates.”

Carroll Rivas noted that recent polling from the law center shows that 41% of Republicans and 34% of Democrats believe “some violence might be necessary to protect the country from radical extremists.”

By continuing to post disinformation on his social media account about the 2020 election and continuing to label his prosecution as an unfair and dangerous “witch hunt,” Trump and his allies are only fanning the flames of the anger felt by his base, Carroll Rivas said.

“When you mix significant acceptance of violence with conspiracy propaganda about the fairness and trustworthiness of our elections, it makes for a dangerous situation,” she told USA TODAY.

Pitcavage said the increase seems likely to continue. “All sorts of people and institutions are going to continue to be getting a lot of threats,” including scenarios we haven’t yet predicted, Pitcavage said. “It's sort of like there's a gas leak in the country, and any match might set it off ? but you don't necessarily know who's got that match.”

Investigation: The military ordered big steps to stop extremism. Two years later, it shows no results

Bart Jansen of USA TODAY contributed.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Threats on rise in US: More legal cases in threats of all types