Martin Luther King's unfinished legacy is visible in desperately poor Selma

Fifty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., who preached nonviolent resistance to oppression and war, was shot to death in Memphis. He was 39. He left behind a wife and four children and a nation still riven by the divisions he had devoted his life to healing. Yahoo News takes a look back at his life and his legacy in this special report. Jonathan Darman assesses King as a man who, though not without flaws, had a passion for justice and a conviction that grace can still be found among us sinners on earth. Senior Editor Jerry Adler looks back on the fateful last year of King’s life, beginning with his electrifying and controversial Riverside Church address against the war in Vietnam. National Correspondent Holly Bailey visits Selma, Ala., whose poverty moved King to increasingly turn his focus to economic justice, and finds that not much has changed. Reporter Michael Walsh examines how King almost died in an attack a decade earlier, and how the knowledge of his mortality shaped his ministry and message. Gabriel Noble’s video explains how a new generation of activists draws inspiration from King’s message.

SELMA, Ala. — Joanne Bland was just 11 years old in 1965 when she joined some 600 men and women in a march for voting rights across the Edmund Pettus Bridge here. She was among those who were beaten when state troopers acting on orders from Gov. George Wallace charged the group, attacking them with cattle prods, billy clubs and tear gas.

She was already a veteran activist. Her grandmother had been taking her to civil rights meetings since she was 8, and her church, Brown Chapel AME, was the headquarters for activists fighting for social justice. Though she was not even out of middle school, Bland had already been arrested at least 13 times, taken to jail alongside adults and other children during mass protests over the town’s treatment of black residents.

Fifty-three years later, Bland vividly remembers the screams of terror she heard that day, the squeals of charging police horses, the blood spilling onto the bridge roadway. With her eyes stinging from tear gas, she stepped over people lying so still she thought they were dead. She remembers being knocked down and hitting her head on the pavement, feeling something wet on her face. She thought it was her older sister’s tears, but it was her sister’s blood, dripping from a gaping head wound.

“I thought they were going to kill us all,” Bland recalled.

The nightmarish images of Bloody Sunday, as that dreadful March afternoon came to be known, were broadcast around the world and proved to be a turning point in the fight for civil rights.

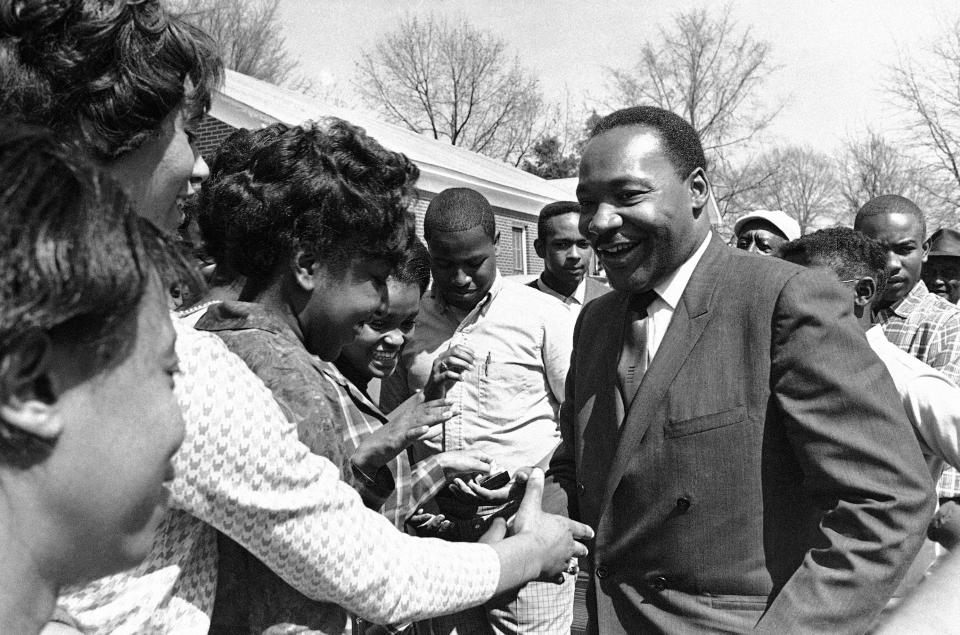

Two weeks later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who had skipped the Bloody Sunday march amid threats on his life, would lead roughly 3,200 people on a historic four-day march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights, culminating in a rally of nearly 25,000 people in front of the state Capitol. That summer, with King at his side, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act, a landmark bill that prohibited racial discrimination in voting, continuing the progress initiated by the Civil Rights Act a year earlier.

Back in Selma, Bland and others rejoiced, thrilled by what the new law could mean for them and their town. They imagined a more diverse political landscape for their city, which back then was almost equally divided between blacks and whites. They foresaw a city government that included black elected officials and believed other positive changes would follow, like more economic opportunity for African-Americans to own homes or start their own businesses. They finally saw their own path to the American dream. “We had just had this major victory,” Bland recalled. “We were so high.”

Five decades later, Bland, who is now 64, looks at her hometown and sees a city that once made history but has seemingly been left behind by it. As she sees it, “Selma is dying,” suffering a slow, agonizing decline that has been heartbreaking and frustrating for people like her who have fought so hard to keep it alive.

While Selma finally has the black representation that many here dreamt of in the 1960s — including a black mayor, a majority black city council and a black congresswoman — the town has struggled amid white flight, a sinking economy, high unemployment, rising crime and troubled schools.

The once bustling storefronts along Broad Street in downtown Selma, where she and fellow activists made history, are now mostly empty and still. The old department store is gone, many restaurants too. The city’s oldest neighborhoods, with their quaint old cottages and 19th-century mansions framed by towering live oak trees, are interspersed with burned-out houses and vacant lots full of tall weeds and trash.

Slideshow: The marchers are long gone from Selma, Ala. The poverty persists. >>>

On the streets near Bland’s neighborhood, countless homes are boarded up — but they aren’t necessarily empty. Here in a city that ranks as one of the most impoverished communities in the nation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, many people are so poor that even homes that would be considered uninhabitable in other towns are still in use by families who have nowhere else to go.

Bland tries hard not to feel bitter when she looks around Selma, a town that spilled its own blood for the civil rights movement but has seemingly gotten little in return. Winning the right to vote wasn’t enough to spare Selma from the social and economic ills that have driven the community and others like it across small-town America into desperation. It’s a downturn largely driven by the loss of industry and jobs, but a struggle that has been felt more acutely in Selma and in other towns along the so-called Black Belt of the Deep South, which has long been one of the poorest regions in the nation and never felt the economic upswing when the rest of the country was booming.

“Selma gave so much to the world, and nothing has been given back,” Bland said. “We have the history, and that’s all.”

And part of that history is the unfulfilled promise of Dr. King, who turned his focus to the plight of small towns like Selma in the final months of his life. In February 1968, three years after Bloody Sunday, King returned to Selma, taking the pulpit at the Tabernacle Baptist Church on Broad Street, where he had pushed those who led the march for civil rights to embrace an even more ambitious “era of revolution.”

Ending segregation and earning the right to vote was just one part of the battle toward equality, King told the crowd. The next step was to take up the plight of America’s poor and reverse economic injustice that was keeping people from having a better life, including there in Selma. “Believe in your heart you are God’s children,” King told the congregation. “And if you are a child of God, you aren’t supposed to live in any shack.”

King called his revolution the Poor People’s Campaign, and he envisioned a movement of poor people from all races coming together to demand a living wage and better access to education and health care. He also wanted to pressure state and federal leaders into doing more to encourage economic development in rural America — not just by creating jobs but also by making sure communities had access to basic amenities like grocery stores and hospitals.

While King took his campaign to big cities like Detroit, New York, Los Angeles and Washington, the civil rights leader spent most of the final weeks of his life traveling across the rural South, where he believed his campaign would have the most impact. It was also where King still had a base of supporters, a crucial detail amid criticism by some in the civil rights movement over his decision to wade into more politically treacherous debates. In April 1967, he had come out against the Vietnam War — a move that was frowned upon by some of his allies, who thought it was diverting attention from the fight for civil rights. His campaign for economic justice was also viewed with suspicion by those who thought it was shining a light on a problem for which there was no easy solution.

King envisioned a rally in Washington that would rival the 1963 civil rights march on the nation’s capital, where he said poor people would camp until federal lawmakers did something about poverty. In the spring of 1968, he visited some of the poorest places in America to rally support for the march, making trips to Selma and remote rural parts of Alabama. He also traveled through the Mississippi Delta, making stops in places like Batesville, Greenwood and Marks — a tiny town in the heart of the state’s cotton belt where many families were so poor they could not afford to buy their children food to eat. In an earlier visit, in 1966, King had broken down in tears after he watched a teacher at a daycare center cut an apple into sections to feed her desperately hungry students, realizing it was all they had to eat.

As he planned his Poor People’s Campaign, King resolved that his march to Washington would begin in Marks, which was then the poorest town in the poorest county in the poorest state in the country. The marchers would travel to D.C. in a caravan of mule-drawn wagons, a potent symbol of the poor black farmers in the South. But King did not live to see it happen.

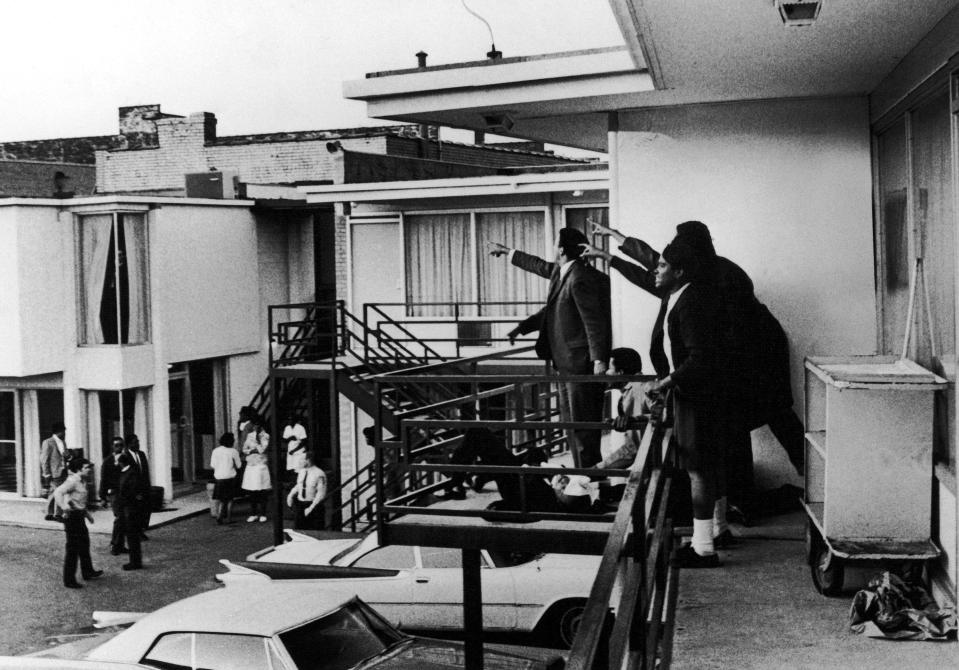

On April 4, 1968, he was killed by an assassin at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. While supporters ultimately did converge on Washington that June, occupying a settlement they called Resurrection City, the Poor People’s March and King’s dreams of transforming the lives of impoverished people, especially in the Deep South, largely faded away.

It’s hard to know what ultimately would have happened with King’s war on poverty had he lived, or what he would make of the state of the nation today, where the divide between the rich and the poor is even more extreme, and where the places he tried to champion face even more dire conditions than they did 50 years ago.

Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in Selma, where the town is smaller, more segregated and poorer than it was during King’s day. Its population of roughly 28,000 in 1960 was down to less than 19,000 in 2016, according to U.S. Census estimates. While the town was roughly split between blacks and whites during the civil rights era, Selma is now about 80 percent black. That divide is more extreme in the public schools, where 99 percent of the student population is black.

The average income in 2016 was $23,283, roughly half of Alabama’s median household income. More than 41 percent of the town lives below the poverty level, according to the U.S. Census, more than three times the national average and one of the highest rates of poverty in the country. Among children under 18, the percentage living in poverty is nearly 60 percent.

In the past 50 years, the town has lost hundreds of jobs, as textile and other manufacturing plants have closed and the agricultural sector has declined. One of the biggest blows came in 1977, when nearby Craig Air Force Base, a pilot training facility and airport that once had a population of nearly 5,000 and contributed millions to the local economy, closed its doors.

Like other small towns, Selma has suffered under state and federal spending cuts, including in agriculture, education and health care. It has been forced to try to do more with less. And with much of the population living below the poverty level, local tax dollars haven’t been there to help the city invest in and improve conditions that might help it attract new industry.

“Black Selmians have fought so hard to try and create economic opportunities, to make the most of the vote, to really improve things for themselves, but they keep fighting with a dwindling pool of resources. It just gets smaller and smaller and smaller,” said Karlyn Forner, a Duke University historian specializing in civil rights who wrote a book about the city’s plight, “Why the Vote Wasn’t Enough for Selma.” “The economic abandonment has been so deep for so long, it’s just an impossible task to be able to solve it [without outside help].”

Outside of downtown, area shopping centers are full of vacancies, including the old J.C. Penney, which closed four years ago. Many buildings sit in empty decay — monuments to a more prosperous time. One of the biggest employers, besides an International Paper plant on the east side of town, is the local Walmart.

While the unemployment rate in Selma has dropped to 8 percent — down from 13 percent in 2015 — few credit the number to people actually getting jobs. They believe many people have simply given up looking.

“To see our town go from the way it was to the way it is now, it’s ridiculous. Boarded-up houses, no jobs. I don’t care what you say, poverty is a form of violence, and people are hurting,” Bland said. “You tell a child that he needs to get a job, that he shouldn’t be waiting for a handout. But there are no jobs to be had. How do you justify that?”

But there is a new push to call attention to the struggle of Selma and the towns that King once championed. On a recent Friday night around the corner from where the Bloody Sunday march began 53 years ago, a few hundred people packed the pews of the First Baptist Church in Selma as a group of activists plotted the revival of the Poor People’s Campaign to try to force the nation to address the tricky question of poverty, just as King had so many decades ago.

The group was led by Dr. William J. Barber II, a black minister and civil rights leader from North Carolina, and Dr. Liz Theoharis, a Presbyterian minister originally from Milwaukee who has spent years working with the poor. Also onstage were other well- known civil rights leaders, including Rainbow Coalition founder Jesse Jackson. Jackson had worked on the original Poor People’s Campaign and was in Memphis with King when he was assassinated.

Collectively, they spoke of initiating a “moral revival” in the nation, with an agenda that includes living wages, health care, criminal justice reform and clean water and air. The campaign also criticizes the nation’s “war economy,” in which the U.S. spends more money on military action overseas than rebuilding communities at home — an issue that even Donald Trump flicked at during his 2016 bid for the White House but has largely ignored as president.

Earlier in the day, Barber and Theoharis had toured some of the poorest areas around Selma, including a rural community in neighboring Lowndes County not far from the historic route of the 1965 voting rights march. They visited homes occupied by the poorest of the poor in the region, where many homes lack sewage systems, leading raw waste to openly flow into yards and often back into the drinking water. That has led to an outbreak of E. coli and hookworm, an intestinal parasite and disease of extreme poverty that is more typically found in developing areas of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

A United Nations official visiting the region last December as part of a forthcoming study on extreme poverty told a local reporter that conditions in Lowndes County and other parts of Alabama’s Black Belt were among the worst he had ever seen in the developed world.

“And this plays out in many communities across the country, but especially the rural South,” Theoharis said later. “This kind of disease and a lack of public health and desperate poverty connected to it… And this is America.”

Two days after the meeting in the First Baptist Church, Barber and Theoharis gathered a couple of blocks away on the steps of the Brown Chapel AME, where hundreds of people had converged to mark the 53rd anniversary of the Bloody Sunday march. An annual event, the Selma Jubiliee, as it is known, includes the re-creation of the march from the church to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. President Barack Obama participated in the march in 2015, and this year the group included nearly 100 members of Congress. Among them were Sen. Kamala Harris of California, who is often rumored as a possible future presidential candidate, and Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, the storied civil rights leader who was beaten on Bloody Sunday.

This year, organizers for the new Poor People’s Campaign were determined to use the annual march to call attention to poverty and other problems facing Selma that have long been ignored by the politicians who descend on the city every year to mark the town’s civil rights history. They fanned out with big yellow signs and handed out fliers, which advertised a planned 40 days of activism beginning in May and leading to a June 23 march in Washington, D.C., modeled after the original Poor People’s Campaign.

But in a series of speeches by civil rights leaders and politicians before the march, the issue of poverty was all but ignored — until Barber took the microphone. He recounted the extreme poverty he had seen among local residents in recent days and criticized politicians who seemed unwilling to even try to tackle the subject, even as they came to march on Selma’s hallowed ground.

“What would Dr. King think?” he said.

In the crowd that day was Joanne Bland, who spends most of her days giving tours to outsiders who come to Selma to learn about the civil rights history that happened here. She loads the visitors up in a van and takes them to the Brown Chapel AME and then drives them to the Edmund Pettus Bridge and then to the other side, where the marchers were first attacked.

But Bland also shows outsiders “the ugly” parts of Selma, the crumbling factories east of downtown that ceased operations long ago, the surrounding neighborhoods with burned-out houses and vacant lots where people deal drugs in the middle of the day and where there has been open warfare among local gangs. She wants them to see what has become of her city.

“I’m not ashamed to show it to them, ’cause sometimes you have to play on the guilt,” she said. “You have to make people feel guilty. We gave you so much. Now look at us. Help us.”

The reactions are often the same, she said — how Selma shouldn’t be like this, how a city that played such an important role in civil rights should be lit up and thriving, how a city that paved the way for politicians like Obama and Harris and Cory Booker shouldn’t be so forlorn. But then they leave, and nothing happens.

In some ways, Bland followed a similar path. After graduating from high school, she moved to New York for college and later joined the Army and was stationed in Germany. Returning to the U.S. in 1989, it was her intention to live in New York — “the big city,” she says — but a visit back to Selma changed her mind. She was troubled by the decline of her hometown and felt drawn to try to do something.

In addition to local activism, she helped found the National Voting Rights Museum and organized the first Selma Jubilee to re-create and commemorate the Bloody Sunday march, building on the city’s historical tourism. But the city continued its long decline.

She still has hope of things turning around. And like Dr. King she has a dream — that one of the many visitors she talks to returns to Selma, buys a house or starts business and does something for the community. Then their friends would follow, and a city could be reborn. That’s why she keeps telling the story of Selma again and again, working day and night to call attention to what she calls a “blight on America.”

“To me social movements are like jigsaw puzzles — everybody has a piece,” she said. “My piece is teaching young people where we’ve been as a nation so they can improve upon what we already did.” But for Selma to survive, she said, “it’s going to take so much more than just me talking about it.”

_____

Read more of our coverage of: