McCain's legacy: Principles tempered by political necessity

At first, John McCain couldn’t hear what some of his supporters were yelling. The roar of the crowd often made it too loud to hear anything, and he was already hard of hearing in his left ear, a condition that dated to his days as a Navy pilot and no doubt worsened because of the beatings he suffered during his 5? years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.

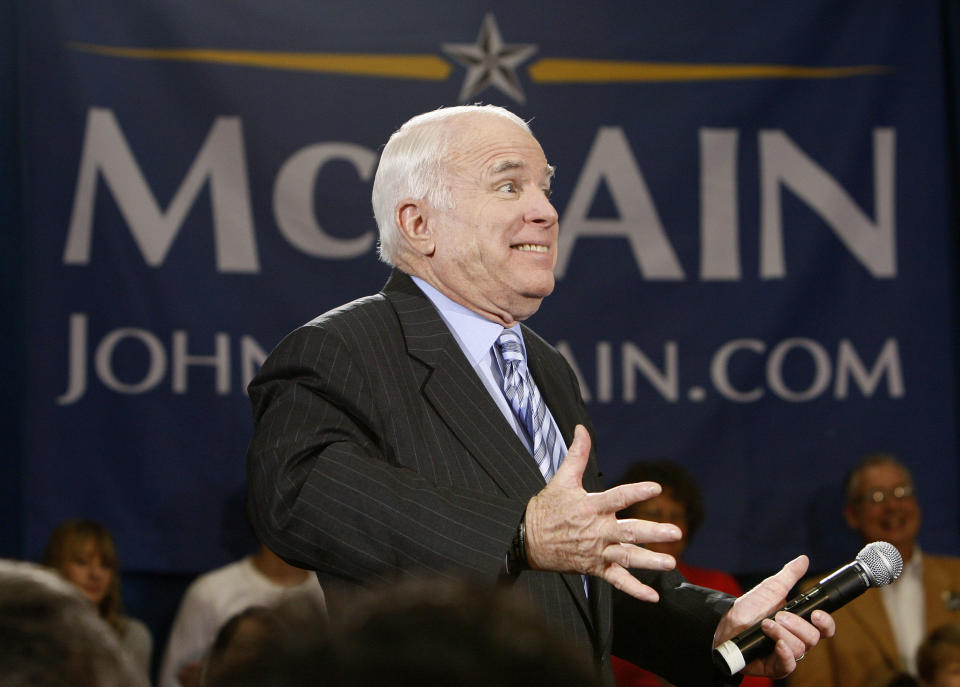

But in the fall of 2008, during his second bid for the presidency, the Arizona senator could tell that the crowds at his town halls were getting more rowdy — something he normally didn’t mind. The town hall was McCain’s preferred way to campaign; it was the format he felt allowed him to truly connect with voters, where people could see who he was, for better or worse. For months, McCain’s aides had been trying to talk him into holding more traditional events, such as scripted speeches, where he could avoid gaffes that could be seized upon by his opponents. But the candidate stubbornly refused.

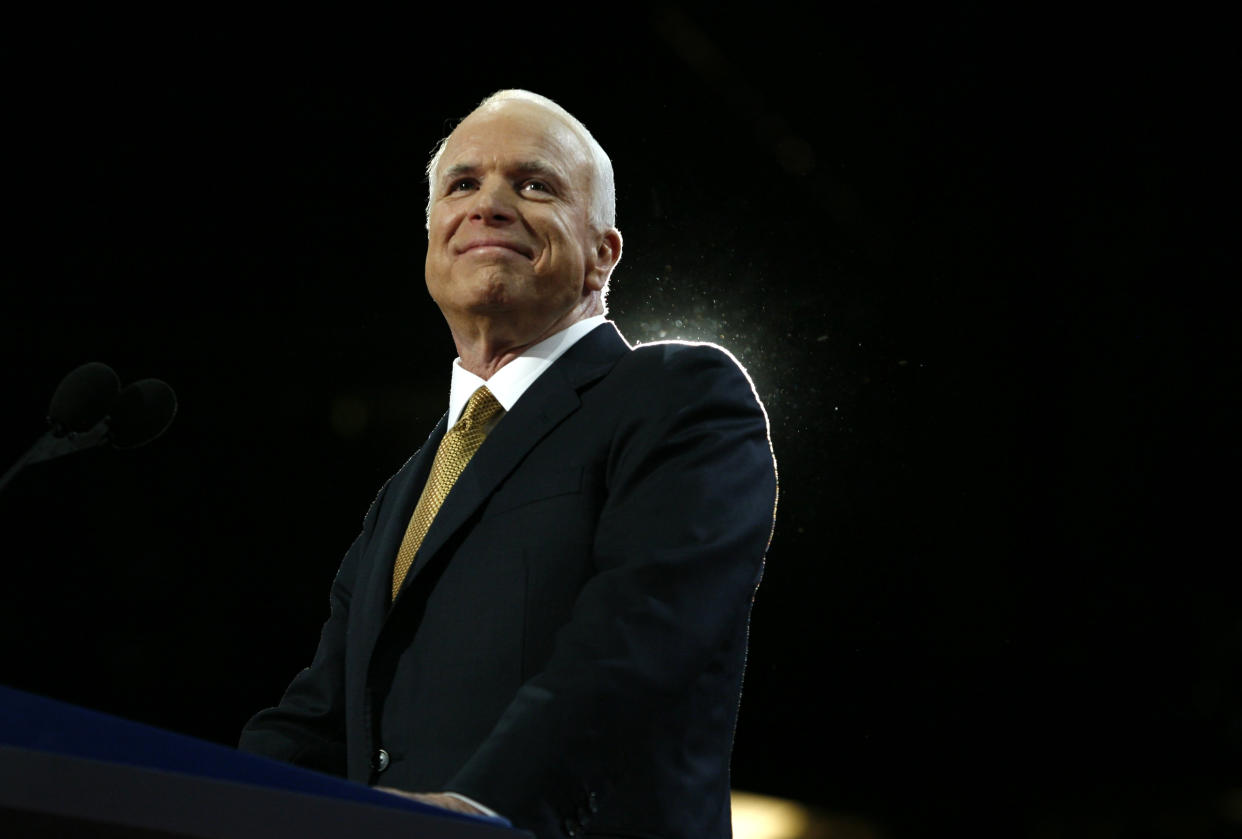

Speaking to a reporter in the back of his legendary Straight Talk Express a few months earlier, his suit jacket off and Ray-Bans on, McCain had scowled at the very mention of his aides’ advice. “I honestly don’t like giving speeches,” he said. He hated being behind a podium. He hated the teleprompter. He didn’t like adhering to a script. It was boring.

But about town halls, McCain said with a glint in his eye, “I love them. I love the back and forth. I love the unpredictability.” His staff worried about protesters, but McCain had already handled more than a few, including a man in New Hampshire who had assailed McCain for his support of the Iraq war. But McCain wasn’t worried. To be honest, the senator admitted with a chuckle, he kind of liked it when the crowds were “a little rowdy.” He enjoyed it when people yelled at him because he could argue back. “That’s democracy,” he explained.

What McCain did not sense, at least at that time, was how angry the electorate was and how toxic the 2008 race would eventually become — a shifting dynamic that would ultimately shape his own political trajectory for years to come. Bubbling beneath the surface that year was the kind of rage and anxiety that, in hindsight, provided some of the earliest hints of the voter turmoil and tribal politics that would later help propel Donald Trump into the White House. Ugly whispers about Barack Obama’s race, birthplace and religion that began during the Democratic primary erupted into full-scale conspiracy theories among some Republicans, including McCain’s supporters.

At a town hall in Ohio that September, just days after he had officially claimed the GOP nomination, McCain was on stage speaking about Obama when someone in the crowd yelled, referring to the Democratic nominee, “Terrorist!” A few weeks later, while McCain was campaigning with his running mate, then-Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, in Pennsylvania, rally-goers greeted mentions of Obama with calls of “Treason!” and “Off with his head!”

After a particularly raucous rally in New Mexico, McCain aides told the candidate about some of the slurs shouted by the audience, and the senator, who hadn’t heard them, was shocked. “Where is this crap coming from?” he asked an aide.

It all came to a head in October 2008, just weeks before Election Day, when McCain held a town hall in Lakeville, Minn., just outside the Twin Cities. By then, the senator was no longer the same press-friendly candidate he had been in the primary. His freewheeling press conferences on the bus had come to an abrupt halt that summer after a Los Angeles Times reporter had asked him whether he agreed with a campaign adviser’s statement that it was unfair that health insurance companies covered Viagra but not birth control. McCain’s long silence and struggle to answer the question were captured on camera and widely mocked by opponents.

Afterwards, the senator finally heeded his staff’s advice and barely spoke to reporters anymore, including his traveling press corps. The couch he had specifically requested to be installed near the front cabin of his campaign plane for his rolling news conferences sat behind privacy curtains that had been installed to hide the candidate from reporters. Though he agreed with aides who argued for a more controlled message, McCain looked miserable avoiding the media, whom he had once in jest referred to as “my base.” And he refused to give up the spontaneity of his town halls.

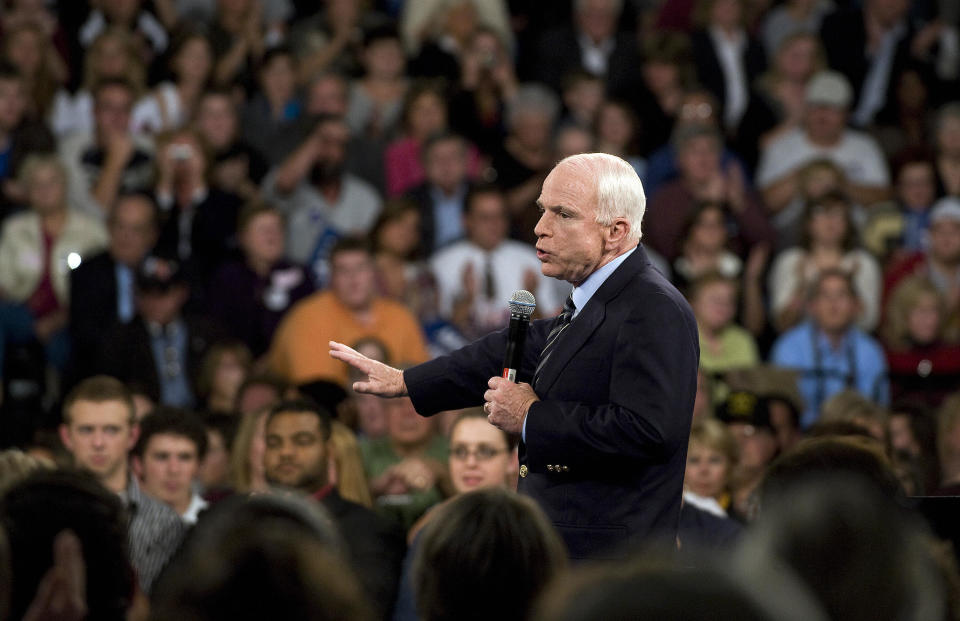

Down in the polls, McCain was in Minnesota looking for a lifeline among working-class voters in the upper Midwest, but what he found were anxious voters who turned their rage on him when he pushed back against attacks on Obama and defended his rival from what would now be described as “fake news.”

When a man stood up and told him he was “scared … to bring a child up” under an Obama presidency, McCain winced visibly. “I want to be president of the United States, and obviously, I do not want Sen. Obama to be, but I have to tell you … he is a decent person and a person that you do not have to be scared of as president,” McCain replied, prompting loud boos and cries of disapproval from the audience.

As he tried to calm the audience, the crowd only seemed to get more riled up. “We want to fight, and I will fight,” McCain said. “But I will be respectful. I admire Sen. Obama and his accomplishments, and I will respect him.”

The audience erupted in loud jeers, including shouts of “Liar!” “Come on, John!” a woman yelled.

“I don’t mean that has to reduce your ferocity,” McCain said, trying to speak over loud boos from his supporters. “I just mean to say you have to be respectful.”

A few minutes later, an elderly woman stood and told McCain she could not trust Obama because he was an “Arab.” McCain shook his head and took the microphone back, interrupting the woman mid-sentence, something he almost never did. “No, ma’am,” he said, correcting her. “He’s a decent family man, citizen, who I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign is about,” McCain said. This time, some in the crowd clapped, but the candidate looked aggrieved.

That town hall would ultimately become a defining moment for McCain, who was widely praised for standing up for Obama, a fellow senator and fierce rival whom he didn’t personally like and ultimately never grew close to. “It was the right thing to do,” McCain told his anguished staff afterwards, harkening back to the code of civility he had tried to follow even if he himself didn’t always execute it perfectly.

The moment previewed tension McCain would ultimately face throughout the rest of his career, especially in the era of Trump, where his personal mission to serve honorably and in benefit of a “cause greater than self-interest,” as he put it, was often pitted against his own desire for political survival. The growing political divide and a lurch toward tribal politics would repeatedly test the Arizona senator’s pledge to avoid the kind of “destructive hyper-partisanship” that he said was ruining the nation’s political discourse — the divisions that McCain, now stricken with terminal brain cancer in the twilight of his long career, is once again appealing to Americans to reject.

In a new memoir, “The Restless Wave,” and in an HBO documentary that will air on Memorial Day, McCain recounts his two presidential runs and time in the Senate, recalling his leading role in fights about campaign finance reform, immigration and foreign policy. He also uses what he readily acknowledges could be his final message to the nation to encourage Americans to rise above the political polarization that has divided the country to “recover our sense that we are more alike than different.”

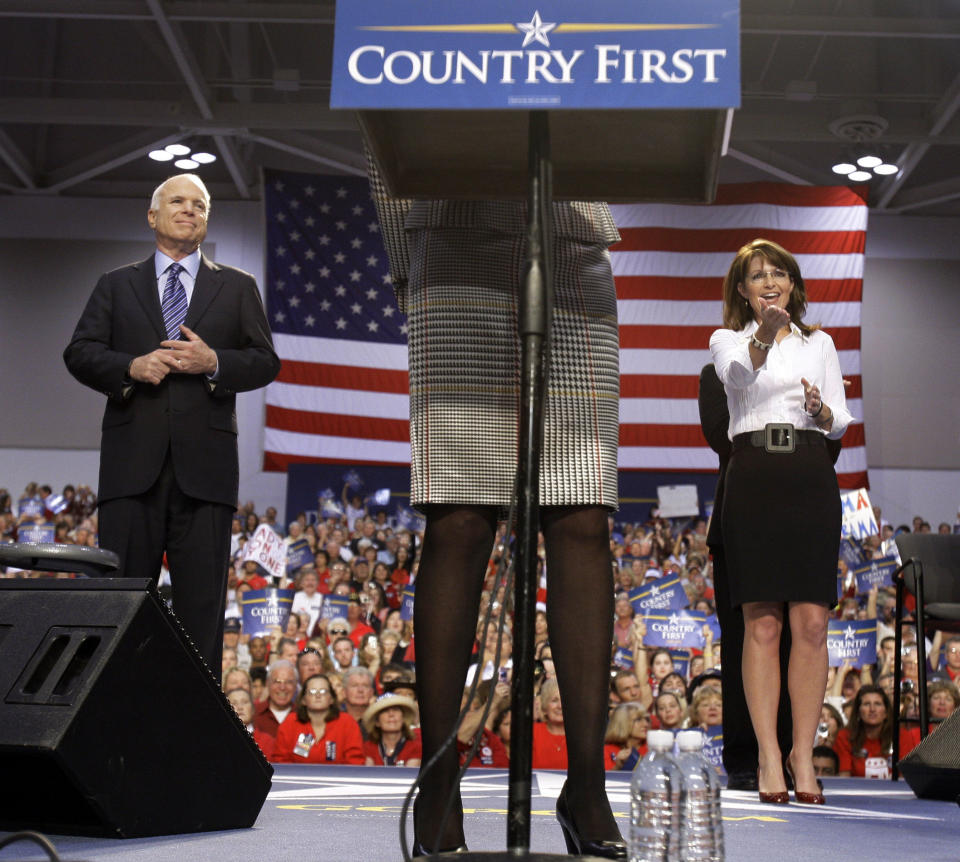

The Lakeville town hall gave public voice to a debate that had been raging behind the scenes at the time between McCain and some of his staff desperate to see him get tougher on Obama. It was a strategy already embraced by Palin, who had willingly and enthusiastically claimed her role as the campaign pit bull.

Plucked from near obscurity in what McCain aides described as the political equivalent of a Hail Mary in hopes of turning the race around, Palin brought new energy and crowds to the GOP ticket but also drama and concern that her fiery attacks and embrace of the resentment and fear many voters felt was diminishing McCain’s brand as a straight-talker who preferred the high road to the gutter.

Days earlier, Palin had accused Obama of “palling around with terrorists,” referring to Bill Ayers, the former Weather Underground radical who became friendly with Obama as a professor at the University of Chicago. She suggested that Obama didn’t care about America “the way you and I do.” Unlike McCain, Palin did not correct supporters who regularly slurred the man they called “Barack Hussein Obama,” yelling out in response to her attacks that Obama was a “terrorist” and guilty of “treason.” At a Palin rally in Pennsylvania, someone reportedly yelled, “Kill him!”

Palin’s tendency to dabble in conspiracy and play loosely with the facts would later set the stage for the arrival of Trump — who, like the governor, embraced and encouraged the increasing nativism and anti-establishment fervor within the GOP. Some Republicans argue that McCain, because he picked Palin, bears some responsibility for ushering in the Trump era —though those closest to him vigorously deny it.

McCain, for his part, is silent on the subject. While he praises Palin in his book and in the documentary, the senator also admits that one of the biggest mistakes in his political career was that he didn’t go with his gut and pick his close friend Joe Lieberman, then the senator from Connecticut, to join him on the ticket. McCain aides had argued that picking Lieberman, a Democrat who had switched his party affiliation to independent, would anger Republicans and doom his White House bid. “My gut told me to ignore it, and I wish I had,” McCain writes.

At the same time, Fred Davis, the campaign’s ad man, was among those pushing for McCain to air television spots attacking Obama for his relationship with the controversial pastor Jeremiah Wright, whose inflammatory sermons had caused drama during the Democratic primary. Another aide had suggested going after the candidate’s wife, Michelle Obama, raising questions about her politics and what policy role she might play in the White House. But McCain flatly refused, telling aides it would stir up racial sentiments he didn’t want to bring up in the campaign.

For McCain, the decision was more than just choosing to take the high road; it was personal. He had not forgotten the racial smear directed at his own family during the South Carolina primary in 2000, when supporters of Bush (their identities aren’t publicly known) papered cars outside churches and McCain events with nasty fliers. They suggested his adopted daughter, Bridget — then just 9 years old — was in fact his illegitimate child by a black prostitute. The McCains were sick about the impact this might have on Bridget and planned to wait until she was much older to tell her about it. But Bridget, who was 17 when her father became the GOP nominee, had discovered the slur in early 2008 when she Googled herself.

A day after the Minnesota town hall, McCain was deeply hurt when John Lewis, the Georgia congressman and legendary civil rights leader who was beaten during the 1965 Bloody Sunday protests in Selma, Ala., likened McCain-Palin rallies to the “atmosphere of hate” pushed by the pro-segregationist Gov. George Wallace of Alabama during the civil rights era. McCain deeply admired Lewis, introducing his kids to him and suggesting that if elected, he would tap the congressman as an adviser. He was anguished by the comparison to Wallace, which he described as an attack that “went beyond the pale.” In the book, McCain writes that he has never forgiven Lewis.

McCain continued to say no to the Rev. Jeremiah Wright attacks, even as one of his frustrated aides argued that simply playing some of the controversial pastor’s sermons on loop would help his struggling campaign. He spent the final weeks of the campaign crisscrossing the country and going through the motions even as he knew in his gut the race was lost. A candidate who was always unable to fake it when he was angry or unhappy, McCain barely made eye contact with reporters when he returned to his campaign plane to bid farewell to his traveling press corps. But that night, he took the stage at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix and graciously praised Obama, acknowledging his history-making election as the nation’s first black president and pledging to work with him.

“A century ago, President Theodore Roosevelt’s invitation of Booker T. Washington to visit — to dine at the White House — was taken as an outrage in many quarters. America today is a world away from the cruel and prideful bigotry of that time,” McCain said. “There is no better evidence of this than the election of an African-American to the presidency of the United States. Let there be no reason now for any American to fail to cherish their citizenship in this, the greatest nation on Earth.”

“Whatever our differences, we are fellow Americans,” he added. “And please believe me when I say no association has ever meant more to me than that.”

But McCain’s return to the Senate and to the campaign trail was complicated by the changing political climate around him. As Arizona turned more red, McCain followed, embracing more conservative positions and turning his back on his reputation as a maverick. He told Newsweek magazine in 2010 that he never liked the label anyway. The man who had once hammered out a bipartisan immigration bill with Sen. Ted Kennedy — which included a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants — ran an ad calling for enforcement of existing laws first. He argued for the construction of a fence along U.S. border with Mexico — even though he had once called the method “the least effective” way of curbing illegal immigration. “Complete the dang fence,” McCain declared in a 2010 reelection ad.

He publicly tangled with Obama about health care and on foreign policy, including the handling of Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, and later the White House’s reluctance to get involved in the civil war in Syria — which McCain has described as one of the most shameful episodes in American history. That led to speculation about lingering bitterness about the campaign, but those close to McCain insist it wasn’t personal. In the final year of his presidency, Obama invited his former rival to the White House, where he closed the door and the two spent a half hour yelling at each other over their differences, according to Mark Salter, one of McCain’s closest and longest-serving advisers. “And they both felt better afterwards,” Salter said. “He admired Obama’s talents.” The former president speaks glowingly of his former rival in the HBO documentary and has reportedly been asked to speak at McCain’s funeral, which the senator is already planning.

There were other moments when he rose above politics, including in 2012 when McCain went to the Senate floor to defend Huma Abedin, a Muslim and a longtime adviser to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Abedin had been accused by then-Rep. Michele Bachman of Minnesota and four other House Republicans of having ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. McCain rebuked Bachmann for perpetuating “sinister” accusations and called the charges “nothing less than an unwarranted and unfounded attack on an honorable woman, a dedicated American and a loyal public servant.”

Calling Abedin a friend, McCain said she represented “what is best about America: the daughter of immigrants, who has risen to the highest levels of our government on the basis of her substantial personal merit and her abiding commitment to the American ideals that she embodies.”

But his relationship with Trump has been trickier. McCain was one of the earliest targets of the former reality television star’s venom. In July 2015, weeks after he entered the race with a rant against illegal immigrants, Trump was publicly feuding with McCain, who had accused the real estate mogul firing up the “crazies” within the party with his inflammatory rhetoric. Speaking to a conservative group in Iowa, Trump fired back, suggesting McCain was “not a war hero.” “He’s a war hero because he was captured,” Trump said. “I like people who weren’t captured.”

McCain didn’t publicly respond. “He just laughed. He dismissed it,” Salter said. “He knew it would make Trump look like an idiot and him look like a war hero, which is exactly what happened.”

But even as he continued to criticize Trump, including about his apparent admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin, McCain — who was facing another challenger from the right in his bid for reelection eventually endorsed him for president. “You have to listen to people who have chosen the nominee of our Republican party,” McCain told CNN. But, he added, he continued to be disturbed by Trump’s rhetoric. “I have never seen the personalization of a campaign like this one where people’s integrity and character are questioned,” he said. “That bothers me a lot.”

McCain later rescinded his endorsement of Trump in October 2016 after the release of the “Access Hollywood” tape that captured Trump speaking in demeaning terms about women. Though McCain has backed some of Trump’s acts as president, including his retaliatory strike at Syria over the regime’s use of chemical weapons, the two have remained at odds. McCain, who was diagnosed with brain cancer last July, came out against a Trump-backed bill that would have repealed the Affordable Care Act — despite last-minute lobbying by Trump and other leading Republicans, including Vice President Mike Pence.

“I’m freer than colleagues who will face the voters again. I can speak my mind without fearing the consequences much. And I can vote my conscience without worry,” McCain writes in his book. “I don’t think I’m free to disregard my constituents’ wishes, far from it. I don’t feel excused from keeping pledges I made. Nor do I wish to harm my party’s prospects. But I do feel a pressing responsibility to give Americans my best judgment.”

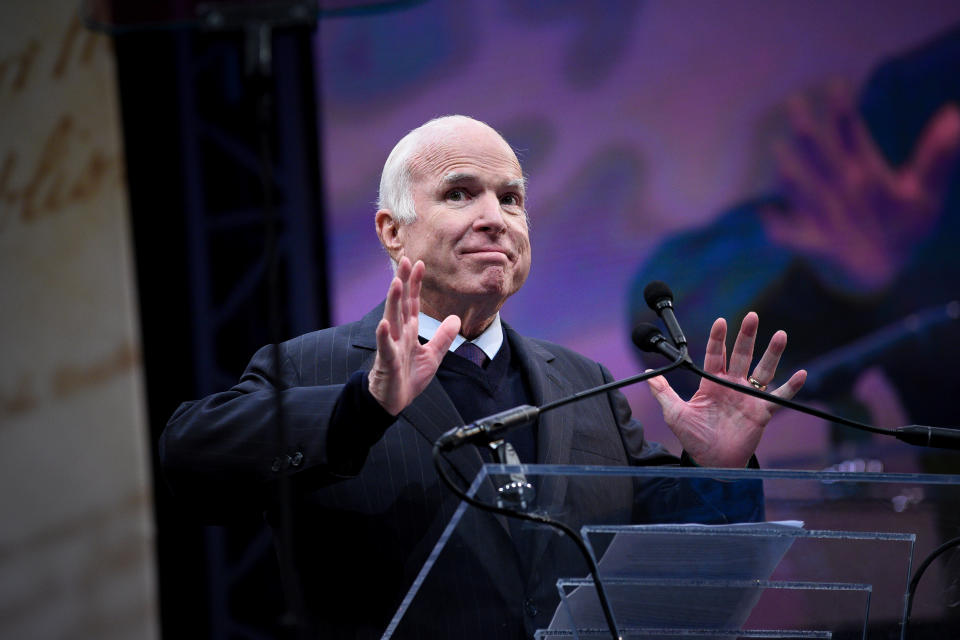

Conscious of his own mortality, McCain has spoken more forcefully against Trump’s divisive rhetoric in recent months. At the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia last fall, where he was awarded the Liberty Medal for his bipartisan work in the Senate, he offered a thinly veiled critique of Trump’s global leadership.

“To fear the world we have organized and led for three-quarters of a century, to abandon the ideals we have advanced around the globe, to refuse the obligations of international leadership and our duty to remain ‘the last best hope of Earth’ for the sake of some half-baked, spurious nationalism cooked up by people who would rather find scapegoats than solve problems is as unpatriotic as an attachment to any other tired dogma of the past that Americans consigned to the ash heap of history,” he declared.

In “The Restless Wave,” McCain takes the critique further, criticizing Trump’s “lack of empathy” for refugees, describing his comments about them “disturbing.” “The way he speaks about them is appalling, as if welfare or terrorism were the only purposes they could have in coming to our country,” the senator writes.

He also criticizes what he describes as Trump’s lack of interest in the “moral character of world leaders” and his embrace of tyrants like Putin. “The appearance of toughness or a reality show facsimile of toughness seems more important to him than any of our values,” McCain writes. “‘Leader of the free world’ is more than an honorific. It is a moral obligation more important than the person who possesses it.”

In his book, McCain writes of his dire prognosis, acknowledging he might not live to see its publication on May 22. Aside from a brief hospital stay last month, the senator has spent most of his time at his 15-acre ranch in a lush valley outside Sedona, Ariz., where he and his wife, Cindy, often sit underneath the towering cottonwood and sycamore trees on the banks of the bubbling Oak Creek. His closest friends have paid visits, including Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and former Vice President Joe Biden, whose son Beau died of brain cancer in 2015.

McCain writes about planning his funeral — which he reportedly has asked Trump not to attend — and his eventual burial at the U.S. Naval Academy in Maryland near his old Navy buddy Chuck Larson, who died in 2014. He speaks of the love he has for his wife and seven children, including three kids with his first wife, Carol Shepp. “Their love for me and mine for them is the last strength I have,” he writes.

In October, he told CNN’s Jake Tapper how he hoped Americans would remember him when he’s gone.

“He served his country,” McCain said. “And not always right. Made a lot of mistakes. Made a lot of errors. But served his country. And I hope you could add ‘honorably.’”

Read more from Yahoo News: