Melania’s fire and fury has deep roots

Melania Trump’s unprecedented public feud with a senior White House official took many by surprise. On Tuesday, after a dispute between the first lady and Mira Ricardel, the deputy national security advisor, Melania Trump’s spokesperson called for the latter’s ouster, saying Ricardel “no longer deserves the honor of serving in this White House.”

This week’s sudden emergence of Donald Trump’s “supermodel” as a source of power in the White House shouldn’t be that shocking. And yet, to most of us, it is.

Researching my book on the Trump family women, I went to Slovenia and interviewed many friends and acquaintances there. I also interviewed sources here in New York and in Europe, where she had a fledgling modeling career before encountering the pageant impresario, ranker of female hotness and soon-to-be reality TV star destined to be her husband.

The picture that these interviews painted was of an incurious girl mainly interested in doodling fashions and scanning the Ljubljana piazza for cute boys on Vespas. Her preternatural beauty landed her early on a career path to which she, an introvert, was not suited — exhibiting herself in and out of clothes for photographers. That she seemed out of place and ill-equipped for a role on the world stage was obvious; that she was married to a bully even more so.

But throughout the research, I also encountered an undercurrent of fear. It was apparent in the terrified villagers in Sevnica, who dared not speak of her or her family. It was in the reports from Slovenian journalists of being shut out for researching even the most innocuous hagiographies, and of being car-chased through the village by a stout, furious, red-faced man speeding in a Mercedes — for the offense of taking a picture of his house. That was Melania’s father.

It was in the chilly smile of the Slovenian lawyer handling the first lady’s case against a magazine and journalist who had reported unsavory things about her past, and who was guarding the perimeters of her privacy and use of her name. And it was in the stack of money — $3 million — the Daily Mail had delivered to her for the same offense, handed over to the same American lawyer, Charles Harder, who had brought down Gawker Media.

To try to understand Melania and what she really wants, then, is to tiptoe into a minefield of litigation and terror where the people who know the way are already hiding from very real threats, both personal and in court. I did that, and managed to fish up a few nuggets that together, I believe, help us understand the mind and motives of a woman from a Slovenian factory town who will never give up her gains and who has always been more interested in security than power, and who, finding herself on a global stage, instinctively acts for a very small audience — her husband, her stepchildren and now, the White House staff.

She prefers a small audience because her past is filled with guarded secrets.

During the 2016 campaign, a reporter named Julia Ioffe revealed one of them — and paid a nasty price. Ioffe went to Slovenia following a tip that Melania Trump’s father, Viktor Knaus, had fathered a son — now an adult — out of wedlock before he married Amalija. After first denying the story, then claiming never to have heard it, Melania conceded the truth when the man himself was found, along with papers proving Knavs had gone to court to fight the mother. Marija Cigelnjak gave birth to a son, Denis, in 1965, and although a court-ordered paternity test proved Knavs was the father, he fought the order to pay all the way to Slovenia’s highest appellate court, Ioffe found. Eventually Melania told Ioffe, “I’ve known about this for years,” and then asked the reporter to respect her father’s privacy.

For that journalistic discovery, published in GQ magazine in the spring of 2016, Ioffe earned an onslaught of vile, anti-Semitic emails and tweets, among the earliest — but not the last — public evidence of the real sentiments in Trump’s base of nationalist “anti-globalists.”

Another old Knavs family friend in Sevnica told Slovenian television that Melanija “married her father” in Trump. The two men are only a few years apart in age, and look alike — both are rotund, given to bellicosity and otherwise all business. Melania’s lawyer threatened her with legal action for talking to the media.

Melania herself has commented on the similarities between Viktor and Donald, though. “They’re both hardworking. They’re both very smart and very capable,” she said. “They grew up in totally different environments, but they have the same tradition. I myself am similar to my husband. Do you understand what I mean? So is my dad. He is a family man, he has tradition, he was hardworking. So is my husband.”

Both men appear to share a habit of attracting legal cases and scrutiny. Besides fighting the child-support order in the courts for years, Viktor reportedly “aroused suspicion for illicit trade and tax evasion” while working as a salesman for a state-owned car company in the 1970s, when Melania was a child. Journalist Ioffe reported that the record was expunged after the statute of limitations expired, and I was not able to find them. When Ioffe asked Melania about the reports, the future first lady replied, “He was never under any investigation; he was never in trouble. We have a clean past. I don’t have nothing [sic] to hide.”

The Knavses have, in any event, been a fairly secretive little clan. Melania apparently stopped communicating with her Slovenian friends after she moved to Milan. A few months before she became first lady, she hired a lawyer there — who now monitors the use of her name and keeps track of inquiries by local and foreign journalists, and old friends who would talk to the media about her past. A close family friend was afraid to communicate with journalists after appearing in a POP TV documentary in 2017, and backed out of an appointment with me minutes before our planned meeting. Another source went away after unspecified threats.

The prohibition against using of Melania’s name on products stings Slovenians the most. It’s one thing for her to refuse all requests to speak to Slovenian television, but to forbid her little country the use of her name seems churlish. Slovenians have got around it by using “First Lady,” a moniker Melania can’t claim to own. The Sevnica tourist office on the little main street sells “First Lady honey,” made by local bees, and First Lady wine (red), made of local grapes. A few uses of Melania’s name have slipped in. The Julia patisserie on the shopping strip does a good business selling a white confection of almonds and white chocolate called the “Melania torte,” displayed beside the apple strudel. A “Donald Burger” can be had at the nearby pub. Other than the cake, though, the lawyer has clamped down hard. When an English-language school in Croatia put up billboards advertising its services with a picture of Melania, the first lady’s lawyer had it taken down with a single call.

The other Knavs family members — Amalija, Viktor and Ines — now divide their time between Trump apartments in New York and possibly a lodging in suburban Maryland, near Barron’s school. Viktor still owns a house in Sevnica on one of the terraced streets just up the hillside from the main strip. The white split-level home has cameras affixed to the roof and a mailbox printed with the words “US Mail.” Viktor is the only family member regularly seen there. He has been known to chase journalists away on foot and in his Mercedes cars.

On Melania’s 16th birthday, a terrible accident occurred that arguably helped bring down the Soviet Union and damaged a vast swath of the Eurasian environment. The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, melted down in the world’s worst nuclear disaster. Chernobyl is nearly a thousand miles from Ljubljana, but the meltdown spewed radiation all over Europe. The catastrophe hastened the breakup of the Soviet Union, a geopolitical cataclysm that would alter the lives of everyone, including beautiful and ambitious women in Eastern Europe.

Uninterested in world events, half-engaged in high school, doodling fashions and checking out cute guys on Vespas in the Ljubljana main square, Melania experienced her 16th birthday as personally significant for another reason. She was tall and skinny, with striking aquamarine feline eyes and black hair, and in January 1987, she caught the attention of a photographer who produced her first modeling portfolio. Stane Jerko was not just any guy with a camera, but Slovenia’s premier fashion shooter. He spotted the teen lounging by a gate outside a fashion show in Ljubljana, where Melania and Ines had been living for two years.

Ljubljana is a charming miniature of classic Italo-Slavic cities. It’s so sweet that it feels like a toy town. The main square is anchored by a pink church with white pillars and adorned by the words “Ave, Gratia Plena!” (Full of Grace). Small cafés line the walk, crisscrossed with a triangle of three little white bridges, along the Ljubljanica River. The snowy peaks of the Alps shimmer in the distance, and sunsets can be spectacular. The food is Italian enough to be good, people bicycle everywhere Scandinavia-style, and the remnants of the socialist system mean there’s not a lot of poverty. In short, it’s a charming place, and in the 1980s, it was safe enough that the Knavs parents felt comfortable sending their girls there to live alone in an apartment while attending high school.

The sisters attended the city’s high school for design and photography, while Amalija held down her clothing factory job on weekdays and visited on weekends. Sometimes Viktor, on work travels, checked in on them, but the sisters were basically on their own. The girls were disciplined and responsible enough to cook for themselves, take the bus for the six-minute ride to get to school on time, and do their homework every evening.

Friends recall them as extremely close, with Ines more reticent and in the habit of wearing “long black clothes,” while Melania, also more a homebody than a party girl, was dressed à la mode and went everywhere perfectly made up, with subtle amounts of foundation and eye makeup. Every morning at 10, the girls would leave school, go to the same store, and buy yogurt and bread for a snack, and return to class. Melania’s social life consisted of hanging with a few friends, sitting in front of the school, and watching cute boys ride up on Vespas. Her first boyfriend would be one of the guys on the Vespas, an athletic guy a little older who would eventually become a male model. Remembered high school pal Petra Sedej: “She always liked good-looking guys.”

But she was no partier. Her life was calm, uneventful and low-key. The sisters spent evenings in their apartment with a few friends, drinking juice. Neither girl showed much curiosity about or aptitude for languages, history, science or current events (although Melania would much later say she learned about the world watching CNN International). They lived for fashion and drawing.

The girls were more well-traveled than the average Slovenian in the 1980s. Ines and Melania had gone on vacations beyond the borders, and were still visiting Italy fairly often with their mother during high school. But teenaged Melania wasn’t yet interested in living abroad. She and Petra went on double dates with their boyfriends and spent their downtime looking at fashion magazines.

“She drew fashions all the time, and was really into looking at English or Italian Vogue,” Petra recalled. “Everything she wore was designed and made by her mother or her sister. I still remember the pink swimsuit she wore to our graduation trip to the beach in Dubrovnik, homemade by her mother: a two-piece, pink with a little white elastic.”

During high school, Melania started taking modeling lessons. Her friends remember watching her practice her catwalk strut. She wasn’t a natural on camera. Photographer Jerko recalled her first photo shoot with him. She turned up with a basket of her mom’s homemade designs. She was nervous and stiff. But Jerko thought she had the basic elements of a successful fashion model. He eventually produced a portfolio for her. “She was never euphoric. She was quiet, kind, hardworking, did not complain, which is why she did not attract attention,” he recalled later. “But I recognized a potential in her that is difficult to describe. It was clear there was something about her, some energy that she has.”

A source of her energy lay primarily in her unusual coloring — black hair and vivid blue eyes. “She was a special kind of beauty, not the classic type,” a former friend from Ljubljana has said. “She had eyes that were kind of psychedelic. You look in those eyes and it was like looking in the eyes of an animal.” Although she had some training and the portfolio, Melania didn’t head straight to to the catwalks of Milan after high school. She still regarded modeling as a side gig, not her vocation, and after she graduated from school with a specialization in industrial — not fashion — drawing, she took the entrance exam and got accepted to the University of Ljubljana, entering the school for architecture and design after graduating from high school in 1988.

An older architecture student and former teaching assistant assigned to proctor one of Melania’s earliest architecture exams recalls what happened next: “I was working at the university. I had been there for four years. And I remember her because she was a bomb. The other girls were average-looking girls — there were no good-looking girls applying for architectural studies! And when she came in — wow. She was wearing jeans from Italy or Paris, cut so you could see the meat, with chains, and sunglasses on top of her head. Nothing wrong, just stylish and nice.”

Her first year’s first architecture exams were divided into different segments. In the morning, the students were tested together as a group, asked to draw perspectives, which they had studied. The afternoon session was individualized; it assessed creativity and imagination. Students came in one at a time, were handed a sheet of paper, and were asked to draw, on the spot, a rendering of the buildings and features of the town where they came from.

“The question was, just try to put on paper how you would present this place where you lived and studied,” recalled the proctor, now a Slovenian architect. “If you are going to be an architect, you would put in this river, this church, the castle — and do it with some energy.”

The proctor gave Melania the assignment and waited, but quickly became alarmed. “Oh my God — after about fifteen minutes, there was nothing on the paper. It was still completely white, and she was standing there, with all her beauty, against the wall — just shaking and shaking; trembling, nervous. Knowing, I think, that she couldn’t pass the exam. She was sad. She didn’t talk with any energy. It was almost like depression.”

After that, he says, “She was not at the school. She vanished.”

Before the Republican National Convention in 2016, Melania’s website stated that she had graduated with a degree in architecture “at University in Slovenia.” But reporters who looked into it found no “University in Slovenia” or a “University of Slovenia.” And the University of Ljubljana had no record of Melania graduating with a degree in architecture.

Nine days after the election, the new President-elect Trump’s website contained a new account of Melania’s college years. The official government website bio stated that Melania “paused her studies to advance her modeling career in Milan and Paris.”

It did not say whether she graduated.

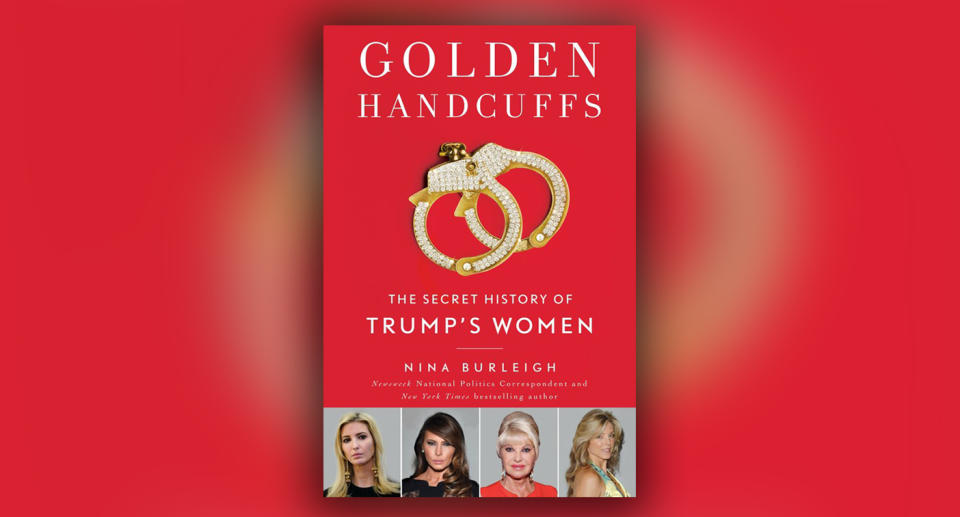

—Adapted from the book “Golden Handcuffs: The Secret History of Trump’s Women,” by Nina Burleigh. Published by Gallery Books, a division of Simon & Schuster.

Nina Burleigh is national politics correspondent at Newsweek

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The CIA’s communications suffered a catastrophic compromise. It started in Iran.

Ending the Qatar blockade might be the price Saudi Arabia pays for Khashoggi’s murder

How Robert Mercer’s hedge fund profits from Trump’s hard-line immigration stance

Trump’s target audience for migrant caravan scare tactics: Women

Photos: Heartbreak in Northern and Southern California areas ravaged by wildfires