Michael and his 3 parents: The first open adoption babies come of age

Although this is the first time she has ever been in this room, there are signs of her everywhere. It’s in the family crest on the wall — the one her ancestors brought from Mexico more than 100 years ago, the one she sent to the young man who is now showing her around, back when he started delving into his roots. It’s in the prescription bottles on the bedside table, medications to calm the racing thoughts they both experience. And it’s in the diploma from an elite private school, representing her dream for his education.

It’s a big room, larger than any bedroom she’s ever had. It’s in an elegant, airy house, filled with mid-20th-century furniture and carefully curated artwork, in a neighborhood of Providence, R.I., that he describes as “a very white place.”

His tour continues through the kitchen, where she takes in the spread of fruits, bagels, juices, coffees and a homemade French-toast soufflé with freshly whipped cream. “Everything here is so perfect,” she says. “I think your Mom is trying to be perfect to show me I made the right choice,” and he nods, although he knows this is just what Mom does for guests. Then into the living room where he shows off the sculptures he makes by pouring molten metal into a bucket of water, resulting in what look like wafers of shiny, frozen confetti.

She listens closely, praises enthusiastically, but soon her attention is drawn to the coffee table, where there’s a copy of the New York Times Magazine from 1998. Inside is a photo of her at 23, her expression somewhere between amused and defiant, her hair showing the wide orange streak she got as soon as her pregnancy was over and she could use hair dye again. “Now Taking Applications for My Baby,” reads the headline. Underneath, the caption says: “A new breed: Gina Bruystens, unlike previous generations of birth mothers, chose the adoptive parents of her unborn child.”

I wrote that article. I have sharp memories of the woman she was then, clearly recognizable in the woman now in her 40s. I recall the days I spent with her, and with the parents she chose to adopt her baby boy, with her own mother, with the head of the agency who facilitated his adoption, even her 5-year-old son who helped select a new family for his baby brother. (He liked the fact that the new parents had two dogs.) Everyone had something to say back then about this infant’s future, and I quoted them all — everyone, of course, but the newborn at the center of the tale.

Which is why we are all here together today.

“My name is Michael James Matt,” he had written in an email to me out of the blue a few months earlier. “19 years ago you wrote an article about me and my adoption. I would love to talk to you sometime about that article and how things have played out in the long run.”

News stories are snapshots. They capture what is true, or what seems most true, as the shutter clicks. They aim to stay out ahead, but almost the moment they enter the world they are literally yesterday’s news. Sometimes the very existence of an article changes the tale; often time and circumstance overtake it. Whatever the reason, the end of a news piece is really just the beginning of the story.

The yellowed magazine Gina holds in her hand is itself an example of journalism as a time capsule. The issue is focused on motherhood, each article a profile of a different “kind” of mother, together forming an album of what felt most important, and most new, about the role. There’s the single mother by choice, the breadwinner mother, the stay-at-home mother, the mother of multiples, all in a 100-page package (advertising was robust back then) titled “Mothers Can’t Win.”

Gina, on page 58, was “The Birth Mother,” an example of the shifting balance of power in adoption. The days when a baby just appeared in an agency worker’s arms to be handed to a waiting couple were long gone, but the era of the newly empowered biological mother and the varying degrees of open adoption she could demand were not quite yet the norm, the story posited.

My editors assigned this general subject because it was universal. (“She is typical of the 1990s birth mother,” I wrote, staking claim to the importance as a trend.) I chose this particular family because they were singular. A unique tale of a 23-year-old woman with bright orange hair and a precocious 5-year-old son, trying to do better for her second boy than she was able to do for her first. You wanted to find out what would happen to these people.

But I didn’t learn what would happen. Readers didn’t either.

Was I right about the norms of adoption? Was it at a turning point for the field? Has open adoption turned out as expected — better for the child, for the biological mother, for the adoptive parents? Or were there unintended consequences? Was Gina, in turn, right about her choice for her baby? Was his adoption in fact open, or did his first and second parents have different ideas about what that term should mean? Were the criteria she used in sorting through the applications the ones that he would have used? What does he think of her choice?

Adoptions like Michael’s are the subject of much more research now than 20 years ago. Harold Grotevant, the Rudd Family Foundation Chair of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, who, with his collaborator Ruth McRoy, runs the 30-year-long longitudinal study on openness in adoption, summarizes his three decades of research like this: “When we started, people were afraid of open adoption, they thought it would be confusing to children, would harm the bond with adoptive parents and would be bad for birth parents because it would not allow closure. We can now say definitively that none of those fears hold up. But we can also say that it’s complicated. Open adoption requires that families be flexible and good at communicating.”

It is a lesson with implications for all the kinds of new families being forged in America today. Relatively few parents now adopt an American-born infant at birth, as the Matts did; it’s now around 14,000 a year, compared with 50,000 older children who are adopted out of foster care. Beyond those are the children of gamete donors, and surrogates, and same-sex parents who ask friends to be donors; more stepfamilies, multicultural families and every other sort of family, navigating the changes in culture and technology that have added new layers to discovering who you are and where you came from.

“The story of the transition in American adoption is also the story of the transition of the American family,” says Adam Pertman, founder of the National Center on Adoption and Permanency. “Broadly speaking, the generation growing up right now has a different definition of family than any generation ever has.”

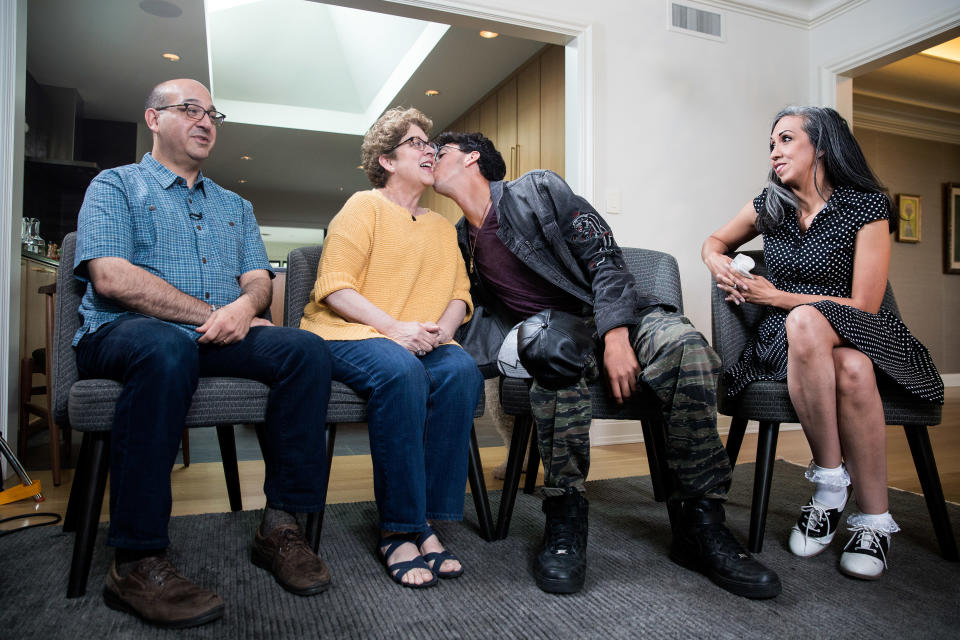

So we’ve gathered again in the Matt family home: Michael, his parents, his birth mother and I, to explore how this one family, representing one data point, has found its way. It is Gina’s first trip to this side of the country. Michael has visited where she lives in Cucamonga, Calif., several times over the years, and his half-siblings (there are now two more) have come to Providence to stay with him and his parents, Judy and Andy Matt. But this is the first time East for his birth mother, who wants to see his life firsthand. She is here because Michael reached out to me, and invited both of us here. He has things he wants to say.

“We didn’t want you to talk to us about Gina and then go talk to Gina about us,” says Judy. Like her husband, she is fair where Michael and Gina are dark, steady where they are impetuous, and deeply private where they are comfortable in the spotlight. They are descendants of European Jews; Gina’s heritage is Mexican Catholic. But they share a love for Michael.

“We don’t talk about each other, we talk to each other. We all did this together, created this family, this, this…” she scoops her hand in a circle that includes Andy, Michael and Gina.

“Well, you do talk about me,” Michael smirks, then adds: “This time, it’s my turn to talk.”

*****

Let’s begin at the end.

“‘You have your son now,'” I quoted Gina telling Judy and Andy in the final paragraph of my article. “I housed him for nine months. I took care of him as best I could. I had the easy part; now you guys have the hard part. You don’t need to check in with me anymore.”

Why did she do that? I ask now. If she wanted an open adoption, why did she begin by closing the door?

“I didn’t want to be that crazy mom,” she answers. “The one constantly calling to ask, ‘What’s he doing today?’ ‘Did you pack him a good lunch?’ ‘Is he eating enough vegetables?’ I didn’t know what the term ‘open adoption’ meant. I just knew I wanted to be some part of his life.”

And Judy and Andy — was this their idea of how things would work?

“I was a little relieved” by Gina’s approach, Judy admits. She was less interested in creating some sort of extended family with Gina than making it possible for Michael to access his medical information as he grew. “You are able to open that door as wide as you want, or just ajar, and that’s how we felt — at least let there be an open door, and we’ll open it as needed.”

While there is only one way to do a closed adoption, there are countless ways to do an open one. “One thing we know for sure is that one size does not fit all,” says Deborah Siegel, a Providence psychologist who has been studying several dozen adopted children at seven-year intervals for more than 25 years. “Is an adoption open because the original and the adopting parents exchange information with each other at the start but then drop contact? Is it exchanging cards with pictures at the holidays? Knowing that the child might look for you at age 18?”

And like biological parenting, like all parenting, “any one adoption changes tremendously over time,” she continues. “It can go wide open and then shut down. People can back off or lose touch, and maybe they find each other again. All adoptions are de facto open nowadays, because little-bitty kids who don’t even own a computer can find their birth parents from their friend’s house,” or, at least can give that search a try. “But how both sets of parents work things in that new norm is an evolution.”

All three of Michael’s parents see this now, but at the time, all Gina knew was that this new way gave her more of a say than the old way, while Judy and Andy believed that more information was always better, and because birth mothers liked this new way, if they were to get a baby, they would have to like it too.

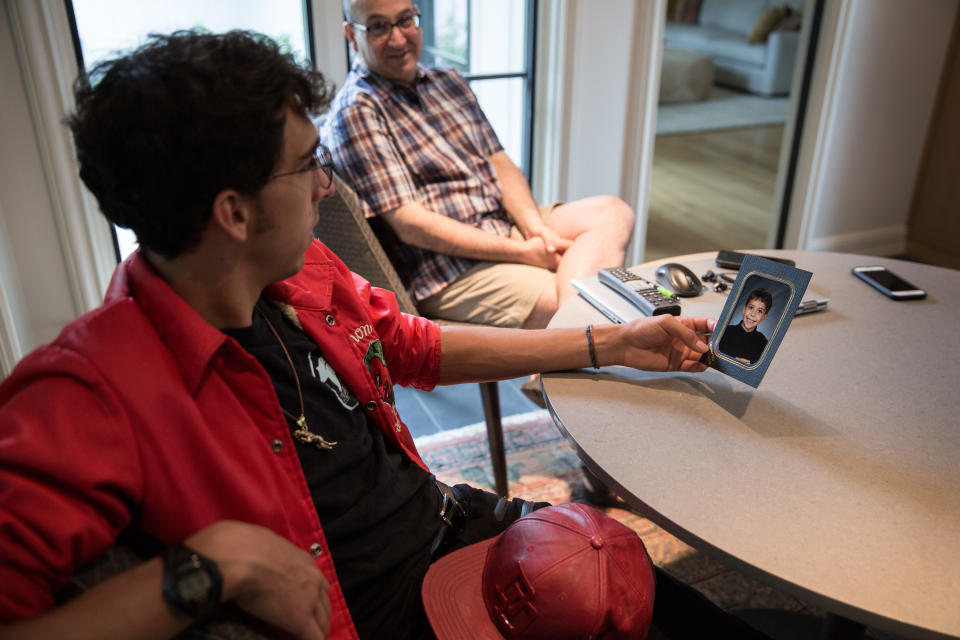

At first the Matts took Gina at her word, and didn’t call for a while. Instead they built a life with their son. Family albums, of which Judy kept an endless number, show a happy little boy with a bowl haircut standing in his crib with pictures of Peter Rabbit, riding on Andy’s shoulders in the local playground, curling up in the dog’s bed, visiting Hawaii, and Disneyland and Costa Rica, and loving grandparents.

Gina, meanwhile, realized that while she had changed Michael’s life, she hadn’t changed her own. Too many sick days early in her pregnancy meant she’d lost her job repairing arcade machines at the local Dave and Buster’s, and now she bounced from one hourly job to the next in Cucamonga — babysitting, exotic dancing, applying cosmetics to the deceased at a funeral home.

While trying to make her way in the world, she dropped the name (Bruystens, the name she used in the magazine piece) she’d taken during a brief early marriage and returned to using Aparicio, the surname she was born with and the one that she’d put on Michael’s original birth certificate until the adoption was complete.

The decade that followed was a jumble of fraught romances, imperfect work experiences and dark episodes of depression. By 2007, she was divorced and out of a job, raising not only her son Andrew but also a daughter from a second failed marriage.

As she went through all this, Gina began contacting Judy Matt. Ostensibly she would call for updates about Michael, but she was also coming to see Judy as stable touchstone, a reminder that while her own life was “a roller coaster in the dark” as she describes it, Michael’s wasn’t. She had spared him that.

“Each time I got into another relationship, I had hope and thought, ‘Let’s start a family,’” she says. “And then that one failed, and then, ‘Let’s start another one,’ and then that one failed. But I picked the perfect family for him, because they provided him stability. That is something that I could never do for my kids.”

In those early years, it was almost as if Judy was also parenting Gina. “The contact was much more between me and Judy than between me and Michael at first,” Gina says.

“Each time she started out on a high, and then there would be the call that it had fallen apart,” Judy says. “We got to know a lot about each other.”

As Michael grew, he became part of those calls. Not to talk about Gina’s love life, of course, but to get on the phone with the woman he knew as “my birth mother” from before he could talk, the woman who had carried and given birth to him because, he was told, “Mommy’s tummy was broken, so you grew in Gina’s tummy.”

“If I was talking to Gina and Michael came into the room, I would let him know that Gina was on the phone and tell him ‘Come say hi!’” Judy recalls. “Or I would say ‘It’s Gina’s birthday, let’s call and wish her a happy birthday.’”

“Adopted” is simply who he was, they agree. For as long as any of them remember, a family mantra was always “Mom has her side of the family, Dad has his side of the family, Michael has his side of the family. … And we’re a family!”

One memorable day, Gina called excitedly and told Judy “put Michael on the phone!” Judy did, and Gina told him, “You’re going to be a big brother!” — her way of announcing that she’d just learned she was pregnant with her daughter.

Michael hung up, confused. “Is that baby coming here too?” he asked.

Judy was none too pleased. “When there’s big important news like that, it might be best to pass it by Andy and I first,” she told Gina later that day, after explaining to Michael why some babies from Gina’s tummy stay with Gina while others live at their house.

Lesson learned. “I wasn’t thinking,” Gina says. “We’ve just been winging it for 20 years.”

*****

As Michael neared puberty and became more pensive and less reachable, the balance began to shift, and it was Judy who would turn more often to Gina for insight and support.

“There’s no book on open adoption,” Gina says. “There’s no directions on how to handle life situations with a mutual child. We would turn to each other a lot.”

From their first face-to-face visit, when Gina was four months along, she had told the Matts about her lifelong history of mental illness — the diagnosis of manic depression in her teens, the impulsive behavior, the anger issues, the despairing moods, the decades of start-and-stop treatment, the trazodone, lithium, Depakote, Wellbutrin, Celexa, Abilify, Risperdal, Prozac, Zyprexa, Seroquel, Lamictal (lamotrigine), Paxil. She assured them that she had not been on any medication during any part of her pregnancy.

They answered that they were prepared to parent a child who might inherit any or all of that.

“You can’t worry about it until it happens.” Andy said at the time. “Mostly, we were impressed that she told us. Our pediatrician said ‘You’re incredibly lucky, because a lot of birth mothers will just say that everything is fine.’” Knowing what was possible would help them look for signs and allow them to get help earlier, in the event that Michael developed similar symptoms.

But it wasn’t that simple. As Michael entered his teens and turned from charming moppet to sullen adolescent, his parents used Gina as their guide. “His mom would tell me that he had anger issues,” she remembers. “That he was rude, he was disrespectful. And I’m like, ‘That’s a typical kid.’ I wanted that to be true.”

Nearly every adoptive parent goes through this part, trying to sort adoption from adolescence. It is a rare child who gets through those years unscathed, and a rare parent who doesn’t wonder whether this is normal or a sign of something more. Most kids will find something to blame their parents for; adopted children don’t have to look very far to find a target for their anger. And now add a biological mother’s history of psychological struggles.

Adoption is a case study of nature vs. nurture. Michael says that for years he directed all his anger at the nurture. When he was unhappy, “I blamed where and how I was raised,” he says. When he was 6, his parents moved from Massachusetts to Rhode Island so he could attend the Wheeler School, a private academy they thought would be perfect for him. His parents were affluent; his mother, a marketing executive, left her job to volunteer at his school. (Judy spent so much time at the school that one of Michael’s friends assumed she worked there.)

“Wheeler was great. It taught tolerance and worked at diversity, but I was still one of the only Hispanic people in my grade,” he says. Nobody picked on him or called him names; instead, “People pretty much treated me as just another white boy, and I hated that more than anything.”

During his freshman year, he overheard one student say to another, “Oh, Michael? He’s not really a Mexican, he’s white,” he remembers. “And I wanted to kick his ass. Growing up a Mexican Jew is weird. It’s something I always felt was lost in the adoption was the Mexican part.”

Another source of distress — more guilt than anger, though sometimes they felt like the same thing — was his keen awareness of his life of privilege compared with the children Gina did not “give away.” Michael would visit Gina and her children every few years, or the Matts would host his older brother and younger sister at their home for weeks at a time, and, well, “Look at this damn house,” he says now.

“They would be barely making it with not a lot of money, and I felt so guilty that I could have all these things that they couldn’t,” he continues. When he raised the uncomfortable reality with his brother, “He promised me he wasn’t resentful,” Michael says. But on visits, he also said things like, “Wow, you don’t have to worry about prices!” or “You don’t have to ration your food.”

His parents knew Michael was struggling emotionally and did what they could to help, though always with an eye toward the delicate and shifting lines drawn in an adoption. They were generous with gifts toward Gina and her children, but they never offered direct financial support, even during the worst of her struggles. “It has been stressed to us by everyone from the very beginning that that could look like exchanging money for a baby, and you don’t ever want to blur those lines,” Judy says.

And while they encouraged Michael to refer to Gina’s children as his brother and sister, with no need to use the “half,” they did not see it as their place to make that official. In 2011, when Gina, in the process of ending yet another tumultuous relationship, found herself pregnant again, she asked the Matts if they would adopt this baby too.

“I said, ‘Hey, you did a great job [with] the first one. How about another one?’” she says. “They got back to me and said, ‘As much as we would love to, we can’t, we’re too old.’”

Gina was disappointed, but not surprised. “In a lot of ways we are all one family, but that only goes so far,” she says. “My choices, my problem, not theirs.” She kept the baby boy, split with the father and kept up her phone calls with Judy, giving and getting advice. Michael was learning Spanish (he would become fluent), joining Latino affinity groups, listening to Hispanic radio. Gina sent a family tree going back several generations and the family crest that hangs in his bedroom; Gina’s mother sent some Mexican recipes, including one for enchiladas that Judy followed as best she could when Michael wanted to bring it to the “Students Involved in Cultural Awareness” potluck at school.

Gina is aware of the irony. “Yeah, I don’t even speak Spanish,” she says. “I was raised on fish sticks and canned refried beans. But I gave wanted to give him culture closure, so I sent what I could.”

Still, he wanted more. For a while he took his frustration out on what he saw as a disconnect with his non-Hispanic name. “I was always unsatisfied with it — Michael Matt, Michael James Matt,” he says. He knew the story of how it came to be: Gina had decided to name him Michael Joseph before he was born, chosen to honor a manager and a security guard at Dave & Buster’s who had been particularly kind to her as she struggled to keep working during her pregnancy. That led 5-year-old Andrew to start calling him “Baby Michael” before he was born. Andy and Judy had planned to call their son James, but they didn’t want to confuse Andrew, so they went with Michael James.

In high school, “when I was young and a jerk,” he says now, he took to threatening to change his last name to Aparicio. He even tried it out on Facebook, where Gina discovered it and told his parents. He remembers them not understanding. They say they tried.

Eventually, they told him more about his mother’s psychiatric history. He was 16, the age Gina had been when she was diagnosed, and his initial thought was, That makes a lot of sense.

There were times he was all but paralyzed by anxiety, and a moment when he grabbed a kitchen knife and threatened to stab himself. His parents saw all that, but also a boy who was so much more: student body president, captain of the varsity cross-country team, president of Latino and adoption affinity groups, a peer-support counselor at school and an Eagle Scout who loved hiking in the wilderness.

He says he worked hard at keeping most of his struggles to himself. “It’s not on them that they didn’t know,” he says now. “I did a very good job of not letting them.”

But he would open up in his talks with Gina, and find solace there, because he didn’t have to explain his roller-coaster brain — she already knew.

As he neared his 18th birthday, he began talking with her more. He would call just to talk, with Judy’s encouragement, despite the occasional moments when she worried that her son might come to love Gina more. For Gina’s part, she was glad she could help her child, but came to the disquieting realization that she was the control in this nature/nurture experiment. Michael had inherited his volatility from her, he had a genetic makeup similar to his three half-siblings’ — but he was raised in a stable family, by parents who knew in advance what problems he might face and could provide him with resources and treatment. How would he turn out? How might her own life had been different with his advantages?

When she would tell him about her older son dropping out of school, or about the ongoing custody fight over her youngest son, with an ex who wanted to change the child’s name to his own, or her worries about her preteen daughter who was foundering at school, she would often add: “This is why I gave you away, so this wouldn’t be your life.”

Michael, too, saw the path-not-taken theme as his world diverged and intersected with Gina’s, and he hatched a plan. He had become increasingly close with his sister now that the girl was a young teenager, serving the role for her that Gina served for him. Two summers earlier, she came to visit for 10 days, the longest time they had spent together, and for the first time at his home rather than hers.

“We really got to know each other,” he says. “Before that, all she knew was the guy Gina put on a pedestal. Michael … he’s student body president. He’s a varsity athlete. But that’s not all of me. She got to know my demons. She got to know the real me, the flawed human being, her brother.”

He also learned more about her. “The school she was in — the teachers didn’t care,” he says. “And my education was so important in how I grew up. Something I valued endlessly. I wanted my kid sister to have that too.”

So he pitched an idea to his parents: “Would you be OK with housing my sister while she went to high school at Wheeler?” She could apply for a scholarship slot at the Wheeler School, then live in his old bedroom while he was away at college.

Pointing out that he was asking them to provide “parenting, not housing,” Matt and Judy agreed. Michael helped her with the application. If accepted, she would get a chance to live something like his life, with all its imperfections, blessings and complications.

*****

It was near the end of his freshman year at Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., that Michael first learned about the article in the New York Times. It was Gina who slipped up and inadvertently told him.

They had been in more regular touch now that he’d left home for school. “I would talk with my parents on the phone once a week,” he says, “and then I started calling Gina, maybe not once a week, but pretty often. No offense to my parents, obviously, but I get more personal with her.”

Gina welcomed the calls even as she worried about “stepping on anyone’s toes.” She was full of questions about his college life. After all, that was why she gave him up in the first place, she says, so that he would get the education that she hadn’t had and knew she wouldn’t be able to provide.

He tended to call late at night East Coast time, while he walked long loops around the campus in the dark. He would talk of his plans to major in theater, to become a director, of his love of writing and performing rap music, of how nearly everyone at Hamilton called him “Ricio,” the name he started using as a DJ at the school’s radio station. Short for Aparicio, but less threatening to his parents than changing his surname. They don’t mind; all three of his parents still call him “Michael.”

During one of these calls, Gina mentioned something about the long-ago magazine piece. Neither remembers exactly what she said, but they agree that Gina immediately apologized. “It was not my place to tell him,” she says. “That was up to his parents. He’s not legally my son. They’ve done a phenomenal job at molding him, and it’s not my place to provide that information.”

Andy and Judy had decided it wasn’t their place to tell him either. They would have preferred he never see the piece at all. They had participated reluctantly back then, only at Gina’s request, and they asked me to keep their family name out of the story. “Michael had no control over the situation, and we didn’t know how he would react to this article 20 years later, when he read it,” Andy says.

Once the piece came out, they were all the more concerned that Gina had revealed far too much to me. “There were items in that article that weren’t age-appropriate,” Judy says, specifically how Gina worked as a “couch dancer” at a strip club into her fourth month, going by the name of Ginger. “So we put it off, and we put it off, and then we forgot about it. And then Gina let the cat out of the bag.”

Were the Matts angry? “You take a deep breath and you say, ‘Everything is for a reason,’” Judy says. If she and Andy had ever given Michael the article, she fears he would have seen it as an implicit attack on Gina. But as it happened, “Gina shared this with him about herself. We didn’t have to do it.”

Gina had remembered the title, so back in his dorm room, he Googled “Now Accepting Applications for My Baby” and read it through more than once. The parts he found most surprising — and most distressing — were not the ones his parents had feared.

The greatest revelation was that he was almost given to another family. Sitting in her bedroom 20 years ago, looking for an application that met her requirements, Gina first settled on a couple from Southern California — a Hispanic man and a Caucasian woman, the same racial makeup as Michael. That couple backed out, however, largely because they felt Gina lived too close. Which is why she ended up pulling Judy and Andy from the pile.

Learning all this for the first time, Michael felt “conflicted. As you know, racial issues were a huge stress on me growing up. I thought, What would it have been like to be in a situation where I would have been the same race as my parents?”

His own response surprised him. “I got placed in the right spot,” he says. “I’m now sure about that. I’m a Rhode Islander right at my heart. I am a Mexican-American true to myself, and, although I don’t do much with it anymore, I’m Jewish. I’m who I am supposed to be.”

And there was another takeaway. Until he read her words from the past, he had not realized how empowered Gina had been by her choice, what a fresh start for both of them his adoption was meant to be.

“If she has learned anything over the past nine months,” I wrote in 1998, “it is that she is in control. …Time was when surrendering a child for adoption was a desperate choice made by young women, girls really, who were victims of circumstance. But there is nothing desperate or directionless about Gina. She could have chosen an abortion. She could have opted to keep her baby. Her decision was not desperate but deliberate. It was not about helplessness; it was about control.”

*****

Now, months after the fact, it all blurs together: the play, the suicide, the breakdown. But while they were a cascade, they were also discrete and separate pieces. And it was the play that came first.

As an assignment for a scriptwriting class, Michael received a small grant from Hamilton to produce a play he wrote titled “Forsaken: Narratives of Facing Adoption in America.” He was still writing and rewriting as he began his sophomore year, trying to capture a lifetime of feelings and turn them into art.

Then, on the afternoon of Sept. 26, 2017, one of his closest friends at school killed himself. “When Isaiah took his own life, that’s when everything hit the wall,” he says now. He took two weeks off, but stayed on campus. His grief was so raw and deep that his Hamilton friends made sure he was never alone.

Andy and Judy went to be with Michael within a few days. They found a changed person — grieving, but also eager to open up about everything he’d kept from them.

Seeing the pain caused by Isaiah’s suicide, he says, made him realize “I could never do that.” Growing up, he says, “I had a lot of moments where I thought I might end it. And there were times that I got close, but there was always someone that I called,” who reminded him “how much I mattered. After Isaiah’s death, I was like, ‘I can never do this, I couldn’t do that to my parents, I couldn’t do that to Gina, I couldn’t do that to my siblings, and I really can’t do that to my friends. If you can’t live for yourself, you have to live for other people.”

So he told Andy and Judy everything, more even than he had admitted to Gina. “I basically just opened it all up and was like, ‘This is really what I’ve been going through my entire life and I’ve kept this from you until now.’” He showed them the burn marks from lighted cigarettes and the scars on his hands that he’d blamed on sports injuries, but now admitted were the result of “punching things since I was a young kid” — concrete walls, trees, and, on one occasion, a tiled bathroom wall, which resulted in a trip to the emergency room.

His parents were relieved that he felt free to open up about these things, but shaken by the disclosures. That turned to shock a month later when they returned for the staging of his play. He had told them it was a mixture of memoir and fiction, but they weren’t prepared to hear a character named Michael say: “I’m not sure I’ve ever truly bonded with my mom. Like, I love her, but I don’t really like her, you know?” The boy in the play fights constantly with his mother, who says things like: “Gina may have given birth to you, but she’s not your mother. I raised you.”

The fictional adoptive mother is a never-married woman who is killed at the end of the play, meaning that Michael erases both parents from his life.

“Is that how he really feels?” Judy was thinking as the lights came up. “Why didn’t I catch it? Why didn’t I know this about you?”

Michael explained that the mother’s death was how the character came to the realization he had reached after the death of his friend. The fictional character loses his chance to tell his mother he appreciates all she has done for him. The play is Michael’s attempt to say the same to his actual adoptive parents.

“The point of the show is that no one is perfect,” he says. “It’s not putting the blame solely on me and it’s not putting the blame solely on them. It’s saying that this is a situation that none of us could have done perfectly. Life is about figuring it out as you go. As Gina has said my entire life, There is no book on what we do. And the show is a reflection of that.”

When he returned to school after Christmas break of 2017, Michael lasted just two weeks before returning home in a state of desperation and panic, waking with nightmares of ghosts pinning him to his bed by his wrists. He was diagnosed with depression and other disorders, though not the manic depression that had afflicted Gina. He spent the rest of the spring and summer as an outpatient, on medical leave from school. He got a job at a local nursery and spent his off-hours working on his metal sculptures. To his regret, his sister was not admitted to the school he’d hoped she go to. But mostly he focused on healing, and surprised himself by the true peace and comfort he felt living at home.

*****

Gina sits at the Matts’ kitchen table, mug of tea in hand, exhausted from her red-eye flight from California but still energetic and animated. She cuddles the two Labradoodles. (“My daughter, she wants one of these. I tell her, ‘I can barely feed you, you think I’m going to feed a giant dog?’”) And she fills Judy in on the latest in her life.

She is in love again, with a man she and her daughter rescued from the homeless life of an addict, seeing him through rehabilitation and rebuilding, recently moving into a place of their own. It took a while for her mother to trust Josh, she explains, but now they are close.

“Can I interject?” Judy asks. “Put yourself in your mom’s shoes. She’s got this adult daughter who brings home this homeless man. Give her a break here. That’s a lot to put on somebody’s plate.”

“I got my tubes tied a year ago yesterday,” Gina announces. It’s an apparent non sequitur until she adds: “But I want to give Josh a baby. That’s all I want.”

“Who kept saying: ‘Get your tubes tied’?” Judy says of the advice she had been giving Gina for years. “You don’t need any more children in this world,” she says.

“Yeah,” Gina agrees sadly. “But the thought of tying my tubes after finally meeting the man of my dreams broke my heart.”

She goes on to talk about her daughter, who is having serious mental health issues, including thoughts of suicide. Gina fought for the kind of treatment she didn’t realize was available until she watched Michael receive it.

“I got her into a program like the one Michael was in,” she says. “Part inpatient, part outpatient. It’s not the usual thing for our crappy low-income insurance, but I got her in.”

And in another iteration of their evolving family relationship, Michael, who spent this fall semester back at Hamilton, doing well emotionally and academically — has become a source of advice for both mother and daughter. Gina calls to ask how he felt, what interventions worked, whether the girl should be tested for his diagnoses of ADHD and executive-function disorder, whether she should take medication. He, in turn, calls his sister and can say, “Look, I’ve been there.”

“It’s definitely a milestone in our relationship as siblings,” he says. “I can speak to her like no one else because of this troubled state we’re both in.”

His life is also a blueprint for his youngest brother, the one Judy and Andy did not adopt. After years of arguing over custody, Gina gave in. “I gave him up to his father, so I could get him into a private Christian school that I could never afford,” she says. “He lives with his Dad full time and goes to a remarkable school that I absolutely love. I did it again. I gave up another kid so he could have an education.”

As she talks, she eyes Michael closely, touching him on the arm or shoulder once in a while. Later in the day, he will drive her around his neighborhood, visiting the school that is the center of their story, the barn where he creates his art, introducing her to his girlfriend, his high school buddies. And within a few days, Gina will be back in California, on medical leave from work while she cares for her daughter, who is home and apparently stable.

But before that, they will all sit down with me for the interview that Michael has asked for so he can say what he’s wanted to say since the day he first read about himself.

“My whole life happened after that article,” he says.

He wants to use his tiny bit of the spotlight to answer what he sees as the underlying question of my article: Can an adoption be too open? No, he answers. Absolutely not. Can a birth mother be too involved? Again, no.

I tell him I don’t think that was the question behind the article, but he says that was his takeaway. “By describing how what Gina did was new and different, you were basically asking whether it was good,” he says. The story, he argues, posits that adoption was in the midst of changing when he was born, and now what was the exception is now the norm. Gina was newsworthy back then because she was in the first stages of an experiment for which there are now results, he says, and he is one of those.

“You wrote how my parents adopted me from Gina,” he says. “But it turns out that we all adopted each other.”

Sitting to one side of him, Gina tears up. “I am so proud of the family that we have established together,” she says. “I feel that together, cohesively, all of us have helped mold who he is today through our own individual influences.”

Sitting on the other side, Judy’s eyes well, too. “It’s having an intimate relationship with someone you don’t have any history on,” she says. “We had to make it work. We did make it work. You do what you do for your kids. She did what she did for Michael. We’re doing what we’re doing for Michael.”

Reaching for a tissue, Gina says, “If I did one thing right in my life, it’s choosing these people.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Blackwater Beef anyone? Private security company’s founder now sells a different kind of muscle

Plea deal by Russian agent Maria Butina describes 2016 influence campaign

U.S. intelligence sounds the alarm on the quantum gap with China

Trump first wanted his attorney general pick William Barr for another job: Defense lawyer

Photos: French police kill suspect in Strasbourg Christmas market attack