Michael Blakemore, theatre director who worked under Olivier and had hits across six decades – obituary

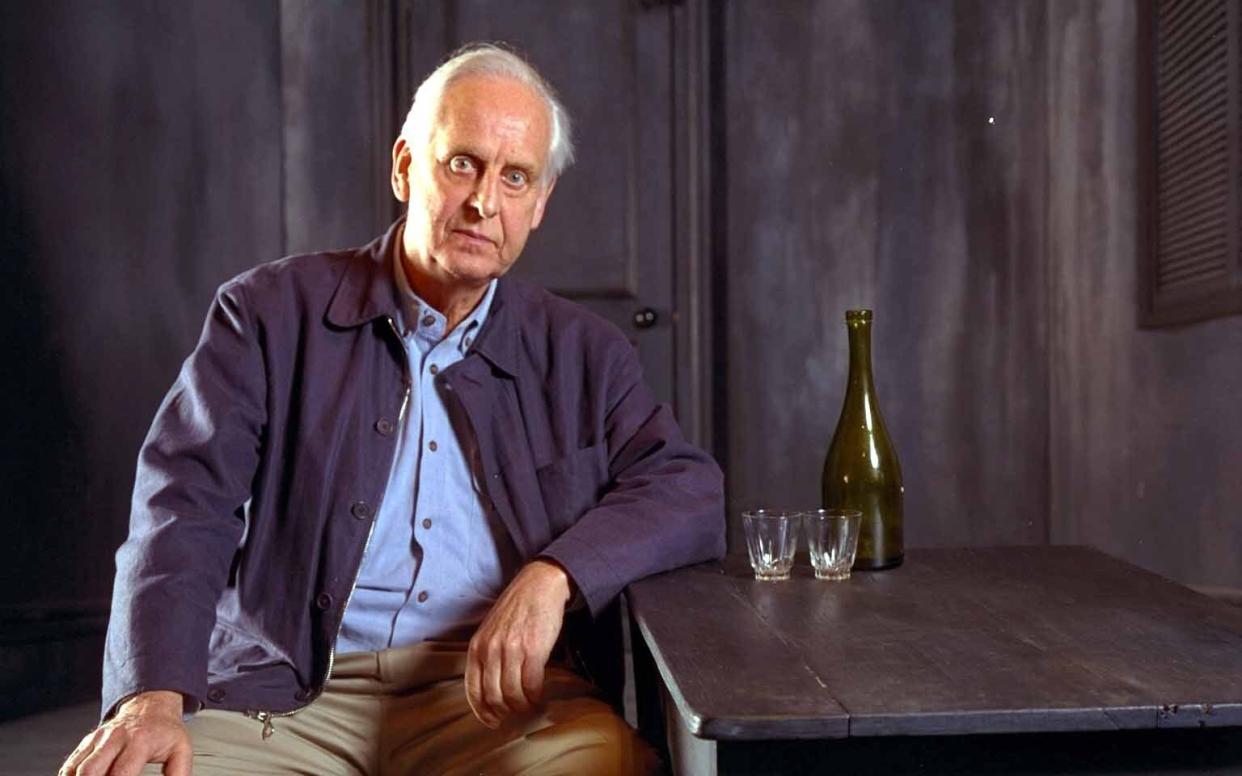

Michael Blakemore, the Australian-born director, who has died aged 95, made his name in London with his premieres of plays by Peter Nichols; he cemented his reputation by staging the majority of plays by Michael Frayn and – in a long-lived career that spanned half a century – became identified as a director with a meticulous eye, a potent feel for the theatrical and a sure touch in the commercial sector.

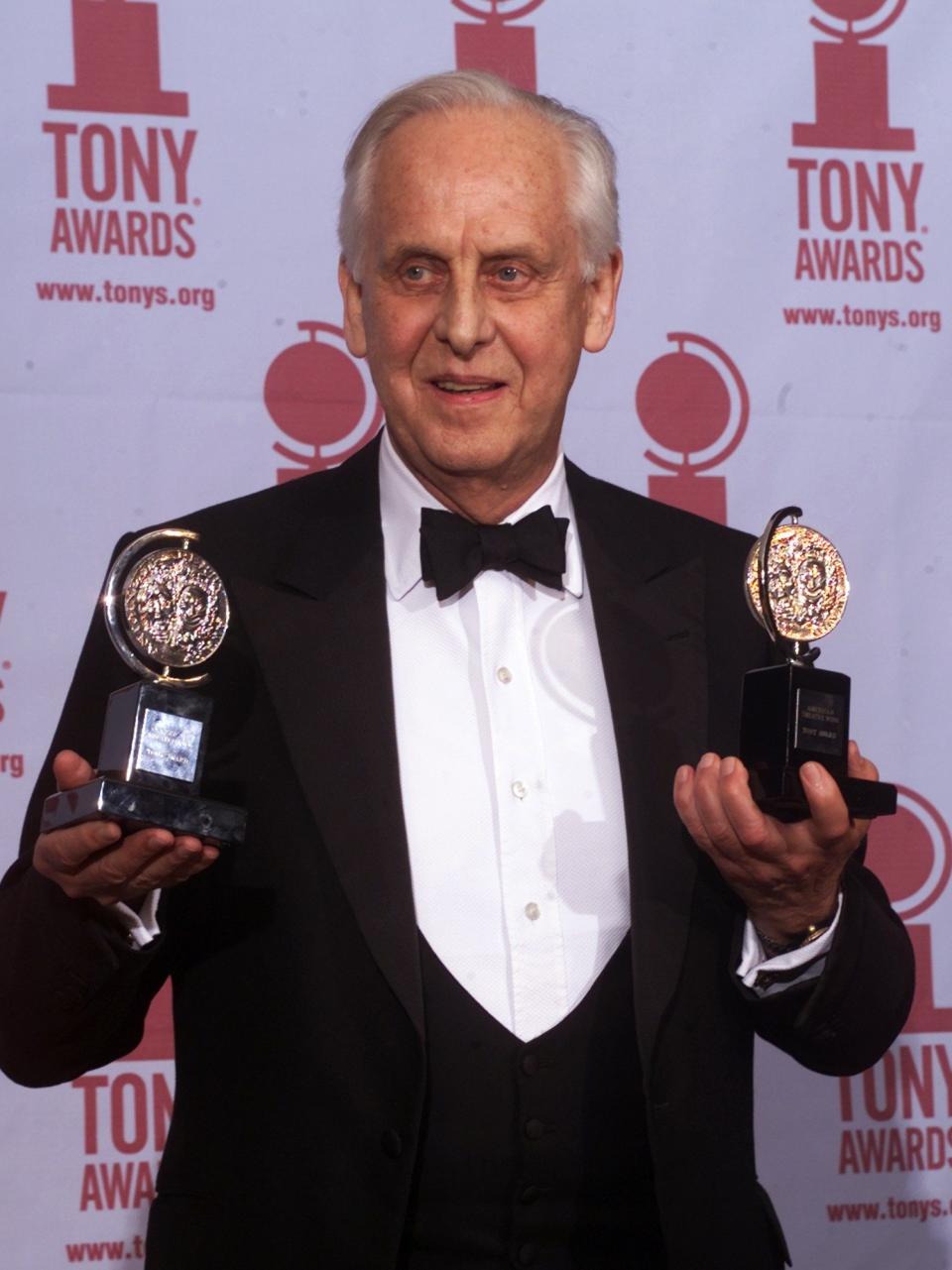

Successful in a number of transfers to New York, he remains the only director to have won Tony best director awards for play and musical in the same year, which he did in 2000 with Frayn’s Copenhagen and a revival production of Kiss Me, Kate.

While not a name as familiar to the wider public as, say, that of Trevor Nunn, he presided over a highly creditable number of hits. His success was notable for his having ascended the ranks having arrived in England originally, and with some success, to make his way as an actor.

He was a perspicacious onlooker, with a flair for writing, and the titles of his memoirs, Arguments with England (2004) and Stage Blood (2013), reflect his independence of spirit, and his battles with that post-war directorial titan Peter Hall at the National – detailed in the latter book – caused some controversy while focusing attention on the way the building was run after it opened on the South Bank.

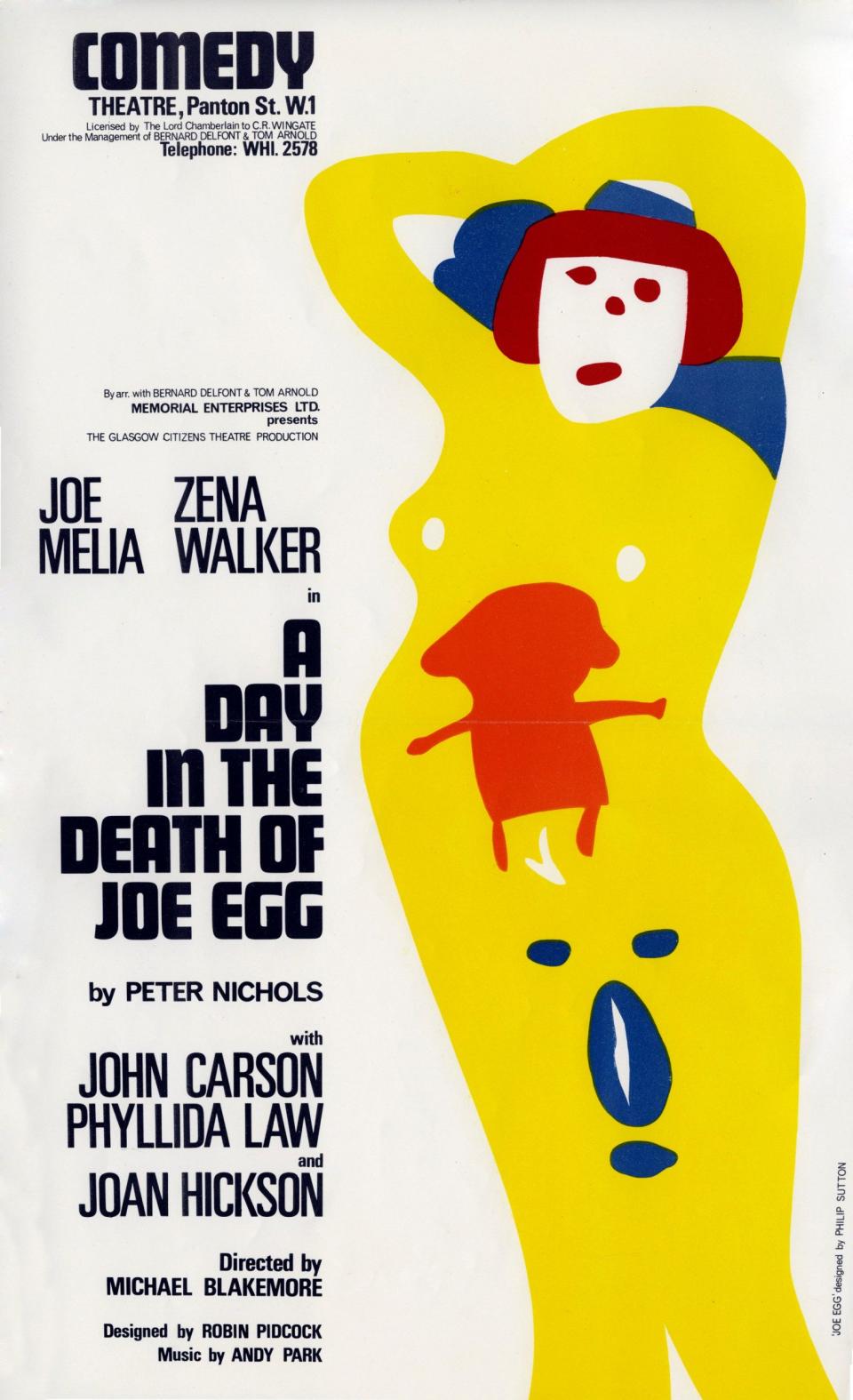

It was for his handling of Nichols’s plays – beginning with A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (1967), which used black comedy to show a married couple trying to care for a severely disabled daughter – that Blakemore first won acclaim. According to Nichols, his agent – the indomitable Peggy Ramsay – suggested that no serious producer would touch it; the BBC declined it. Blakemore, playing leads and sharing direction at the Glasgow Citizens, gave him his only offer of production. It was the making of them both.

He went on to work with a number of leading British dramatists: he was responsible for David Hare’s first West End play, Knuckle (Comedy, 1974), Anthony Minghella’s sex satire Made in Bangkok (Aldwych, 1986) and Peter Shaffer’s Lettice and Lovage (Globe, 1987, New York 1990).

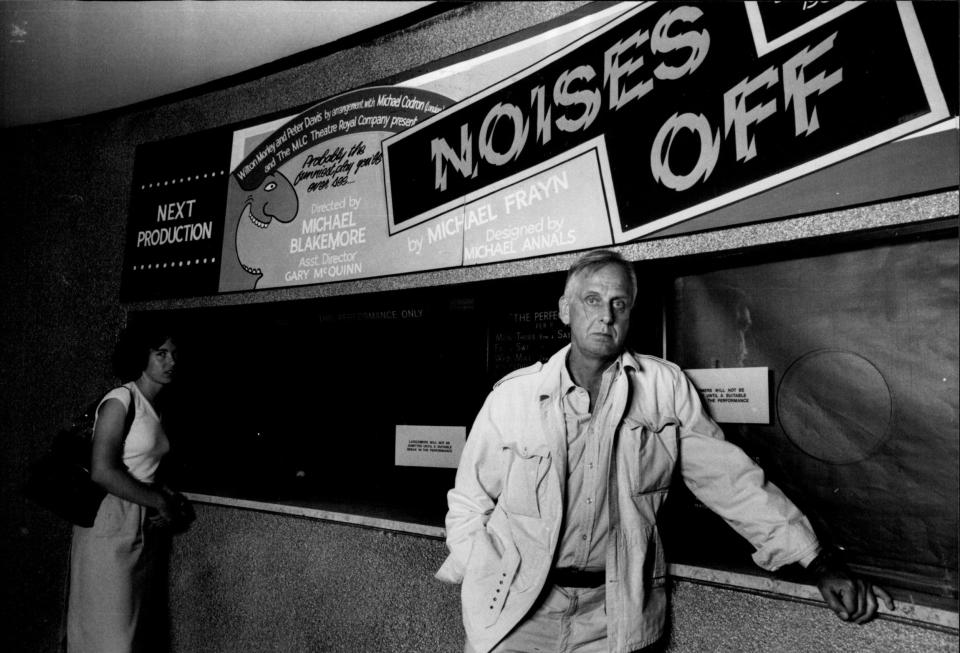

Yet it was his long-running creative relationship with Michael Frayn that yielded the most fruit: Blakemore directed the backstage farce Noises Off (1982), which ran for five years in the West End; in 1998 he scored another triumph with Copenhagen, about the ambiguity-laden meeting between the nuclear physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in war-riven 1941.

In 2003, he worked with Frayn again on his gripping Cold War political drama Democracy, about the true story of the West German chancellor Willy Brandt, whose secretary, Günter Guillaume, was spying for the GDR. Having turned to directing in the 1960s, he was still at work after he turned 90, reviving Copenhagen at Chichester.

Michael Howell Blakemore was born in Sydney, New South Wales, on June 18 1928, and was educated at the King’s School before studying medicine at Sydney University. On screen and on stage, Laurence Olivier made a huge impression in 1945 when touring in Richard III, School for Scandal and The Skin of Our Teeth.

“There had never been a tour of Australia quite like it, and probably there never will be,” Blakemore recalled at the start of his autobiography, Arguments with England. “I wanted even less to be a doctor like my father, even more to be a director, and, a new thought, maybe an actor as well... Somehow or other, I had to get to London!”

He got himself employed as a press agent for the English actor Robert Morley, who was touring Australia in his own play, Edward, My Son, in 1949. “It was a stressful job, and I sweated profusely as I knocked on important doors,” he wrote in Arguments with England. “You’ll have to develop a great deal more personality than you have at the moment if you want to be a director,” Morley advised. “Be an actor. There’s much more work available.”

Young Blakemore moved to London a year later to train at Rada. His first professional appearance came at the Theatre Royal, Huddersfield, playing the Doctor in Rudolf Besier’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1952), after which he entered rep in Birmingham, Bristol and Coventry. His first London appearance was as Jack Poyntz in a 1958 transfer from Birmingham Rep of a musical version of TW Robertson’s Victorian comedy, School (Prince’s, now Shaftesbury).

Tall, long-faced, clarion-voiced and grave-humoured, Blakemore had the makings of a first-rate dry, comic actor. He secured himself a handful of decent minor parts – and some good notices – at Stratford-on-Avon, appearing in a 1959 King Lear that starred Charles Laughton and the fabled Peter Hall-directed Coriolanus with Olivier, though his impressions of Hall as a director were not favourable.

It was a personal and professional antipathy that grew when it emerged that Vanessa Redgrave, then also a supporting actor and with whom he had a brief relationship, had turned her attentions to Hall, while the latter’s then wife, Leslie Caron, was in Hollywood filming.

“Vanessa’s lover was my enemy, the ultimate betrayal,” he declared in Arguments with England. Informed readers of his well-regarded 1969 novel about the life of a jobbing actor, Next Season, suspected that the character of director “Tom Chester” grew out of this resentment. Simon Callow argued that Blakemore revealed “the invisible processes by which the politician director, equipped with a few borrowed insights, a little oily charm and unlimited faith in his own indispensability, hijacks a complex craft from its true practitioners.”

Blakemore appeared at the Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park, in 1962-63, his roles including Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, Holofernes in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing and Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; in the 1963 West End Christmas show Toad of Toad Hall he stole the notices as Badger – “I dropped my voice and made him a cousin of the then prime minister, Harold Macmillan,” he wrote.

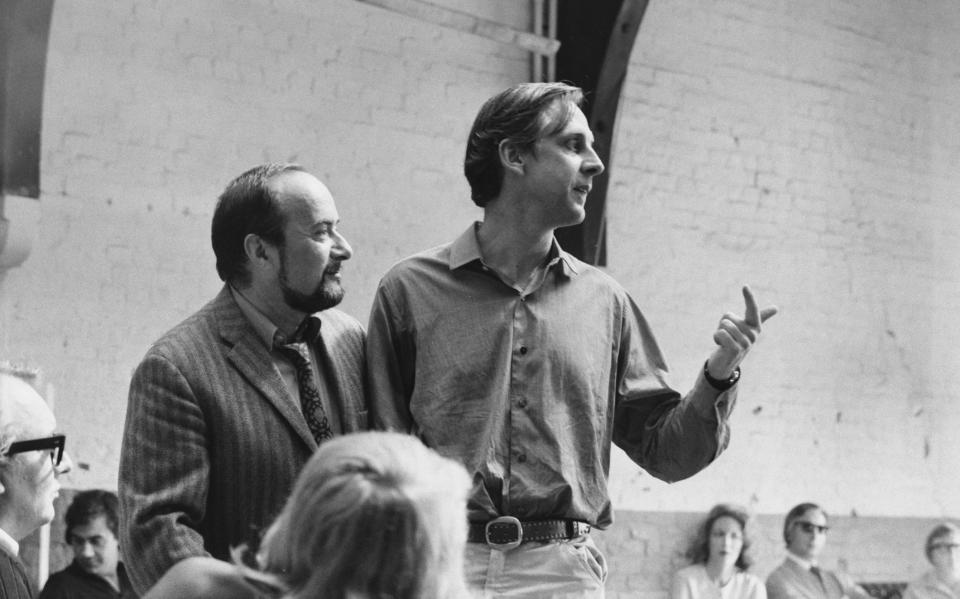

In 1966 he accepted David Williams’s invitation to work at Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre. While playing George in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Maitland in John Osborne’s Inadmissible Evidence, he began directing. Within a year he found himself with the script of one of the most original, if controversial, plays of the decade.

Turned down by other directors as unstageable, and requiring a battle with the Lord Chamberlain for approval, in its attempt to mix poignant suffering with gags, song and dance and music-hall asides, A Day in the Death of Joe Egg was a story of a married couple in their thirties whose 10-year-old daughter had a damaged cerebral cortex – a “human parsnip” her father called her.

What some playgoers saw as bitter courage, others saw as bad taste, especially when it became known that Nichols was the father of such a child, Abigail (1960-1971).

When it transferred to the Comedy in 1967, bringing its author and director fame, the Times critic Irving Wardle wrote “this is one of the rare occasions on which audiences can feel the earth moving under their feet”. Joe Egg transferred to Broadway, with Albert Finney taking the role as the father; Zena Walker, again playing the mother, won a Tony.

Blakemore returned to London in 1969 with another production from the Citizens, Glasgow (where he had been promoted to co artistic director), Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui starring Leonard Rossiter as the Hitler-like protagonist. “You try to imagine any other British actor in the part and realise that he has made it his own,” marvelled The Observer at the tour de force, and the performance remained a reference point for decades afterwards.

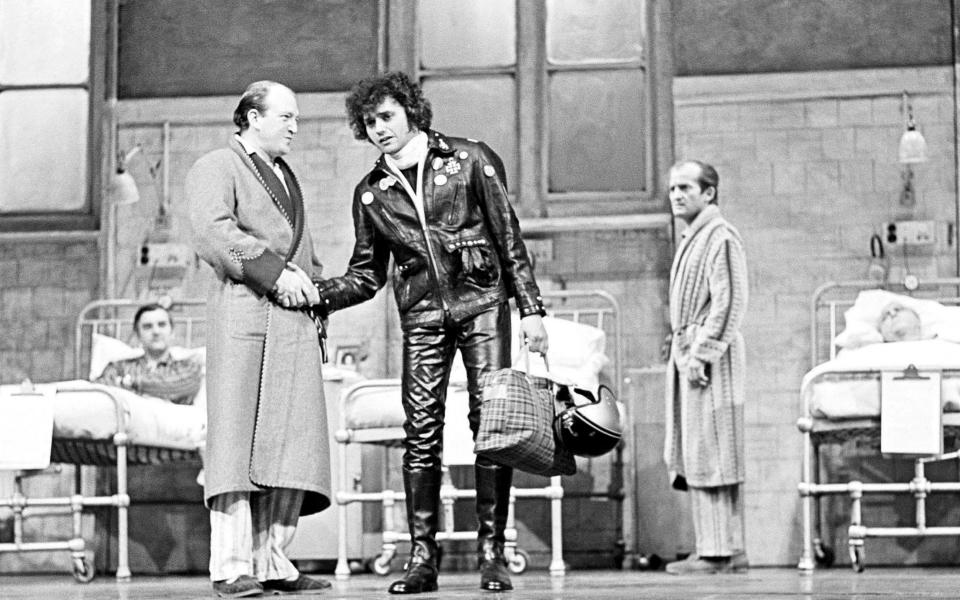

For the National Theatre (at the Old Vic) he had another hit with Nichols’s The National Health in 1969; the subject was the daily life of a ward full of patients in pain or dying while simultaneously on stage there was a rosy-tinted TV hospital soap. Nichols’ family saga Forget-Me-Not-Land was also well-received, at Greenwich (1971).

Blakemore was asked to join as an associate director at the National under Laurence Olivier, whom he directed as the ageing actor James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night. Reviewing the production in 1972, The Guardian’s Michael Billington observed: “Such is the quality of acting and direction, we seem to be not merely watching great drama but to be eavesdropping on life itself”.

He also had a hit with his revival of the American newspaper play, The Front Page (Old Vic, 1972), which brought him the critics’ prize as best director, and success, too, with Ben Travers’s Plunder (Old Vic and Lyttelton, 1976).

But after Peter Hall took over from Olivier at the National Theatre in 1973, Blakemore – whom Olivier had proposed as his successor – showed signs of resentment. By 1976, when the new theatres on the South Bank began to open, relations had deteriorated to a point where, at a meeting of associate directors in March, he distributed copies of an indictment of Hall, which he read out tensely to the assembly, complaining that associate directors only rubber-stamped Hall’s decisions. The purpose, he later argued, was “not to unseat Hall but to bring pressure on him to run the place in a more principled way”.

Hall, who had confided to his diaries at the start of the year that he found Blakemore “as open as a clam”, was upset, and further suspected that he was behind subsequent newspaper coverage of the affair. Blakemore resigned in May.

As a result, among some journalists and theatre grandees, he experienced, he said, “an uneasy relationship for a long time to come”. Yet a fruitful freelance career followed. At the RSC, Nichols’s Privates on Parade (Aldwych and Piccadilly, 1977) presented as a variety show the tragicomic adventures of a British army concert party in post-war Malaya during the “Emergency” (it was later filmed).

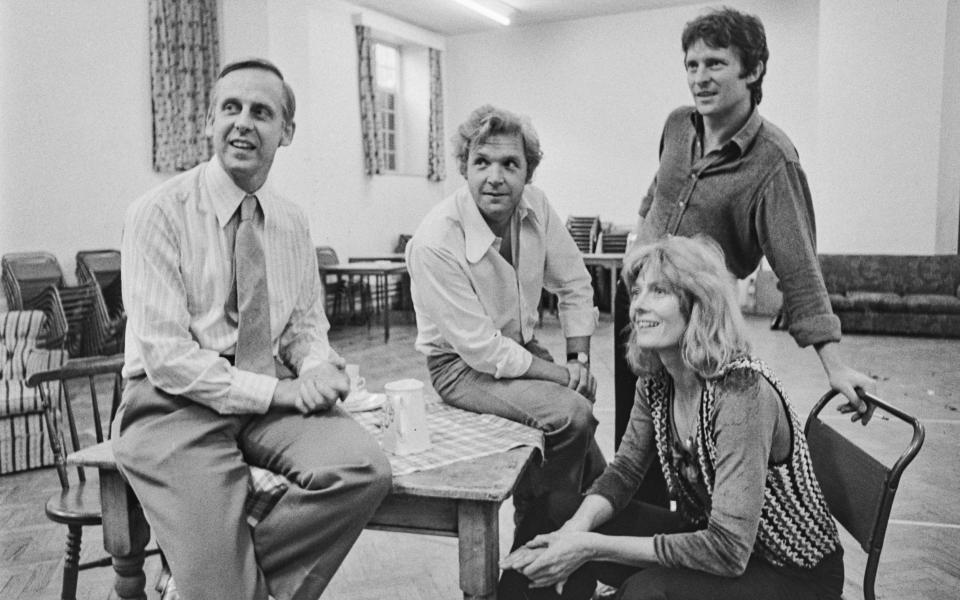

A friendship formed with Michael Frayn after The National Health bore fruit at the Lyric Hammersmith – which he joined as part of the directing team in 1980. Leonard Rossiter was recruited for Make and Break, about a driven businessman, which won the Evening Standard Award for Best Comedy.

Wild success then ensued with the backstage comedy Noises Off (1982), which started at the Lyric and was later described by the New York Times critic Frank Rich as “the single funniest play I ever saw on the job”; Frayn said his director persuaded him to rewrite “a large part of the play and provided a great many new ideas”.

The relationship continued with Benefactors (Vaudeville, 1984), and – after a triumphant, Atlantic-crossing premiere of Peter Shaffer’s Lettice and Lovage, starring Maggie Smith and Margaret Tyzack – a translation of Uncle Vanya (Vaudeville, 1988) led by Michael Gambon, and Frayn’s plays Here (Donmar Warehouse, 1993) and Now You Know (Hampstead, 1995).

Blakemore returned to the National for Copenhagen in 1998; this was followed by Alarms and Excursions (Gielgud, 1998), Democracy (National, 2003), and Afterlife (National, 2008), a rare Fraynian flop. In 1993 he had acted as best man at Frayn’s second marriage, to the biographer Claire Tomalin.

Other notable stage work included three plays by Arthur Miller, All My Sons (Wyndham’s, 1981), After the Fall (marking a return to the National Theatre in 1990) and The Ride Down Mt Morgan (Wyndham’s 1992); and he had success with other American work of quality. In 1989 he directed Cy Coleman’s Tony award-winning musical City of Angels before it was seen in London, and also, on Broadway, Coleman’s musical The Life (1997), about the low-lifes of Times Square.

Blakemore’s production of Is He Dead?, a comic play by Mark Twain, never previously produced, ran for more than 100 performances on Broadway from November 2007. In 2014 he directed a then 88-year-old Angela Lansbury as the comic clairvoyant Madame Arcati in a critically acclaimed revival of No?l Coward’s Blithe Spirit on the West End and Broadway. The Telegraph’s Charles Spencer hailed the production for mixing “the wit and underlying coldness” of the play.

Blakemore tended to gravitate to plays of ideas, ones which disobeyed the rules and often broke the fourth wall. Reflecting on what he and Nichols were after with Joe Egg, he said: “We embraced theatrical energy from whatever source we could find it, and the whole idea was to ambush an audience with the emotion they least expected.” For many decades after that premiere, his passion for theatrical energy was still palpable.

Blakemore retained a lifelong love of surfing from his youth and in 1981 he directed an autobiographical documentary, A Personal History of the Australian Surf. In 2003 he was appointed OBE and made an Officer of the Order of Australia.

He was twice married; first in 1960, to Shirley Bush, with whom he had a son; and secondly, in 1986, to Tanya McCallin, from whom he was separated, and with whom he had two daughters. She and his children survive him.

Michael Blakemore, born June 18 1928, died December 10 2023