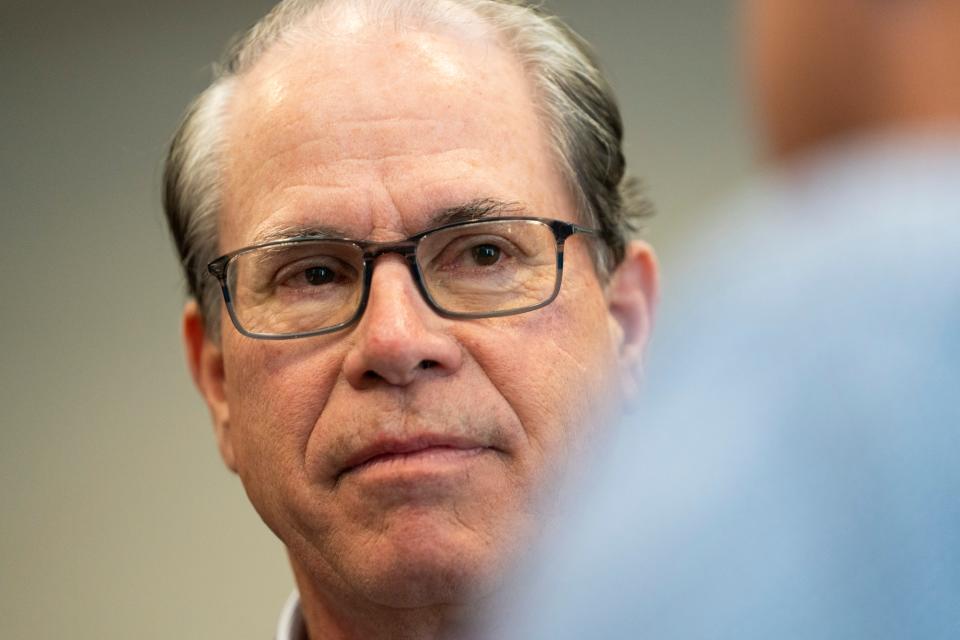

Mike Braun is leading the race for governor. But is his record a liability or benefit?

Editor's note: This is the first in a series of profiles on each of the six Republican candidates for governor.

Read our profiles on Brad Chambers, Suzanne Crouch, Eric Doden, Curtis Hill and Jamie Reitenour.

Naysayers pin Indiana's Republican frontrunner for governor, U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, as a career politician who "gave up" on the Senate after one term ― he was too impatient to make his mark there, they say, so he's giving the state's top job a try instead.

It's true that Braun can be restless. Here's a man who went to Wabash College intending to be a doctor, but, facing down the eight-to-ten-year educational sentence that entails, opted for political science. When the inevitable law-degree trajectory also seemed too long, he switched again, to economics ― two years at Harvard Business School seemed "about right," he said. "Doable."

But this is also a man who, having married his high school sweetheart, waited years to find the perfect piece of property ― a hundred acres of open space in the "country" but still within the Jasper public school district ― and then, because it was landlocked, needed to build a new road to connect it to the nearest access point. (Part of the reason he bought such a cumbersome homestead feeds into another Braun-ism: It was cheap.)

The same man spent 37 years building, pivoting and growing Meyer Distributing from 15 employees to 1,500 before leaving his job as CEO, and a brief stint in the Indiana Statehouse, to go to Congress.

"I was patient in two things that were most important: raising a family and building a business," a suited-up Braun said, moments before mounting a platform with his opponents to make their pitches to an arguably Braun crowd: independent business owners. "In politics, why would you want people lingering a long time?"

In an astoundingly crowded field of six Republican candidates for governor, Braun is arguably the most high-profile, and with that status comes a record that his opponents can easily pick apart ― which they certainly have. He's made numerous political missteps in the Senate, yet he retains a commanding double-digit lead ahead of his competition, owing to his statewide name recognition and the enviable endorsement from former President Donald Trump.

On the campaign trail, Braun isn't just waving the Trump flag; he's focusing too on the kinds of issues he hopes appeals to a broader base, including independents and Democrats: education through a workforce lens, and perhaps more prominently, fixing out-of-control health care costs.

The National Federation of Independent Business members in this small ballroom in Fishers don't need an introduction to Braun. Meyer is still a member of the organization, a fact Braun mentions to most who approach him to shake his hand. Mini conversations broach education, workforce training, the challenge of building entry-level housing.

Then the eight candidates for governor ― including the lone Democrat and Libertarian ― ascend the stage.

Braun does what he usually does. He plays the unflappable, seemingly unconcerned candidate whose race it is to lose (though he says, off stage, that he doesn't take anything for granted). He casts doubt on candidates who haven't "signed the front of a paycheck." He tells the oft-told story about how he decided to self-insure his company, saving his employees from premium increases over the last 16 years and, as he puts it, solving the health care cost crisis in a microcosm.

"I’m the only one they’re coming after, because they know I'm gonna do it, and I’ve already done it in my own business," he says on stage. Cue the smirk from former Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers sitting next to him, for whom a large hospital CEO has rallied support in a last-ditch effort to cut down on Braun's lead.

Braun wants to extrapolate the Meyer health insurance model ― a common model among large businesses, but a gamble for smaller ones ― to state employees and more businesses statewide. Health care cost transparency has been a consistent theme throughout his political career, though he hasn't made many significant legislative achievements in this area. But it is a priority he would have in common with the Indiana General Assembly.

"I don’t mind it," Braun says about challenging the powerful hospital lobby, taking a slow Saturday stroll in more comfortable garb ― jeans and his son's Patagonia jacket ― through Meyer's first major warehouse, located in his hometown of Jasper.

"You can see," he says, gesturing toward the original 25,000 square-foot space, "I’m not afraid to take on big projects."

A businessman takes on politics

The call to run for Jasper school board came in for Braun's wife, Maureen, in 2004. Both were successful business owners. Maureen Braun had had hers, a gift shop on Main Street called Finishing Touches, longer.

In a rural township like theirs, saying yes to a request like this means you're on the school board. These were the days before COVID and Critical-Race-Theory-backlash, when the most excitement might be a disciplinary issue or one rowdy gadfly.

Maureen Braun had been fending off the requests. So Mike Braun filled in instead.

The next opportunity came from another phone call in 2014: from his Republican state representative, Mark Messmer, who was going to vacate his seat and run for state Senate.

Braun's ensuing three-year Statehouse career can be summed up rather quickly. He wrote a few health care transparency bills that went nowhere. He coauthored the signature legislation of the 2017 session, a gas tax increase that Republicans supported because it meant shoring up critical infrastructure funding. And he worked with Messmer on a law establishing a new method of financing regional infrastructure projects, like the now-underway Mid-States Corridor in southern Indiana.

Meanwhile, the Trump effect was taking the country by storm and upending the party establishment reign. Braun fashioned himself a Hoosier version of Trump, the business outsider, and he not only defeated two sitting congressmen in the 2018 Republican primary for Senate but then unseated incumbent Democrat Joe Donnelly.

While the Trump affiliation probably got him elected, his home base in Jasper mainly sees a level-headed business and family man they trust.

Margaret Vaught, owner of party-supply store Occasions of Jasper, said she's known Braun to make decisions based on facts and not "on a whimsy." Her husband, Martin, who worked alongside Braun in his pre-politics days when INDOT brought business owners together to discuss infrastructure in southern Indiana, agrees.

"I haven't seen emotion-driven decisions," Martin Vaught said. "His approach was a very, let's look at the books, what works, what makes sense."

'Most effective freshman Senator'?

Braun has been one of Trump's most reliable supporters in the Senate, having voted twice against impeachment charges and against the creation of the Jan. 6 commission ― though on that actual day of violence, he reneged on his pledge to object to the election results.

Nonetheless, Trump has rewarded him with an endorsement in the governor's race, something that goes a long way with Republican primary voters in a state where Trump won by 16 percentage points in 2020. Braun's television ads frequently feature footage of him shaking the former president's hand.

The other drumbeat he thumps consistently: sharp criticism of the skyrocketing federal deficit. In addition to floor speeches, he's used his vote to protest the trillion-dollar problem, voting against every continuing resolution except the CARES Act during the pandemic.

More: Indiana governor candidate Q&A: U.S. Sen. Mike Braun on the issues

"I’m really disappointed that he’s leaving the Senate because there’s a handful of us who really focus on the budget, and he’s one of them," said Florida's Republican Sen. Rick Scott. "He’s willing to stick his neck out. There’s a lot of pressure not to do that up here."

Braun also seems more concerned than the average Republican office holder about climate change, said Kyle Kondik, managing editor of an elections newsletter by the University of Virginia Center for Politics. Braun cochairs a bipartisan Senate climate caucus and authored a bill in 2021 to reduce barriers for farmers and forest landowners ― among whom Braun should be counted ― to enter carbon credit programs. Language from this bill was included in the 2023 spending bill that Biden signed into law at the end of 2022.

There isn't a landmark legislative achievement Braun can point to, unlike his counterpart in the Senate, Todd Young, who spearheaded the CHIPS act. Many chalk that up to the reality of being a freshman senator, particularly in the minority party.

"It’s the ultimate good ol' boys' club," said Mike McDaniel, executive director of governmental affairs for the Krieg DeVault law firm in Indianapolis and a former Republican state party chair. "If you’re the new guy, it’s like, 'Wait your turn, kid.'"

What Braun does point to is his favorable ranking from the Center for Effective Lawmaking, a project of Vanderbilt University and the University of Virginia. Braun was the most junior among the Center's top-10 most effective Republican Senators for the 117th Congress, which spanned 2021 and 2022.

Here, "effective" means how successful a lawmaker is at moving their own bills through the legislative process. Bills that are commemorative in nature, like the renaming of a post office, weigh far less heavily into the calculation than bills that are considered "substantive and significant," which are controversial or make major changes to code, such as health care reform.

In Braun's case, sheer volume is on his side: He wrote about 80 bills during the 117th Congress, and six became law, which is more than the average senator's 54 bills introduced and four becoming law, according to co-director Alan Wiseman's data.

The Center only tabulated one of those bills as "substantive and significant": the aforementioned 2021 climate change bill.

Sticking his neck out ― to a fault

Braun talks a lot about taking measured risks. It's important to escape the clutches of mediocrity, he says ― turning Meyer from a parts-installer to a parts-distributor, for example, and growing the business even through an early 80s farm crisis and a 2008 financial crisis.

But he found out in his first congressional session that risk can cut both ways.

"You gotta get out there more, and you gotta be careful there, 'cause if you’re off on anything, they can make a commercial out of it and use it against you in your next election," he said.

Braun's 2020 bill to reform qualified immunity, the protection police can claim from lawsuits alleging misconduct, has been the subject of multiple attack ads from his opponents this election. In June 2020, as the country was reeling from the racial justice protests spurred by the murder of George Floyd, Democrats were seeking to eliminate qualified immunity altogether. Braun, calling the current interpretation of the standard "overly broad," proposed limiting qualified immunity only to cases where the officer's conduct is already allowed by law or a previous court ruling.

But he did so without the endorsement of police groups. They considered it an affront to their profession.

Nearly four years later, Braun seems to have regained some ground. The Indiana State Police Alliance, one of those vocally critical groups in 2020, endorsed Braun last week. William Owensby, president of the Indiana State Fraternal Order of Police, said Braun has met with him personally multiple times over the years. As a result of those conversations, Braun has coauthored legislation to eliminate provisions in the law that prevent civil servants who have a municipal pension from also collecting Social Security benefits.

"He’s made a gallant effort to make amends," Owensby said. "He’s not done anything other than support us and listen to us."

Owensby chalks up Braun's previous stance on qualified immunity to a bad decision, caught up in the moment of that summer. But he still thinks it's fair game for Braun's opponents to drag him on it.

"Any misstep you make is subject to be on someone else’s ad," Owensby said.

There have been other missteps Braun has had to explain. He attributed his back-tracking on Jan. 6 to the ugliness of that day's violence. As the Supreme Court was weighing whether to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022, Braun said issues like abortion and interracial marriage should be left to the states; he later said he misunderstood the question.

His recent absence from a critical spending vote also provided fodder for his opponents, who see him as a senator who hasn't lived up to his promises. Rather than partake in what his campaign said was an unexpected 2 a.m. vote on legislation to end the brief government shutdown, Braun was at home in Indiana. Hours earlier he attended a campaign fundraiser.

"Sleeping on the job is a fireable offense for hardworking Hoosiers," Chambers' senior strategist Marty Obst said in a press release, "and it should be for career politicians like U.S. Senator Mike Braun, too.”

Why he's leaving the Senate

Tom Action, a fraternity brother of Braun's at Wabash College, said he'd have never pictured Braun getting into high-profile politics.

Braun was more studious than his brothers, and went home to Jasper most weekends to be with Maureen, Acton said. And then he spent so many years laser-focused on his business.

"As a business person, I said many times, I would never be a politician because I’d go crazy having to jump through so many hoops to get anything done," he said. "That would frustrate me so much, and I think every successful businessman or woman would say the same thing."

Braun said from the get-go he only planned to serve two terms at most. His decision to try going from senator to governor, rather than from governor to senator, is an exceedingly rare one. Braun learned quickly how slow the cogs of Congress move, and just how much seniority, rather than skill, can matter.

"The longer you’re there, regardless of what you produce, you prosper more," he said. "I mean, what job, other than that, would you get a paycheck for continuously?"

He shies away from calling himself "frustrated." Sen. Rick Scott, however, doesn't.

"I think if you’re not, then you might as well sit in a nursing home," he said. "Because it’s a frustrating place. It’s very difficult to move things along here. If you actually want change, it’s a very frustrating job."

Another six years, Braun calculates, might produce only marginal progress on issues he cares most about ― the solvency of the Social Security system, for example. As governor, he feels he can set an agenda and check off accomplishments at a pace he prefers.

After all, Acton said, the job is to be the chief executive of the biggest business in Indiana: the state of Indiana.

Braun would, however, have to work alongside the pace of the supermajority Republican state legislature, which in recent years has morphed into the main agenda-setter in state government, McDaniel said.

"He’s used to saying, 'I want this done, it’ll get done,' in his business life," McDaniel said of Braun. "He’s gonna find out in a hurry that it’s not always that way when you’re governor. That’ll be a learning curve for him."

That said, Braun's priorities ― adding transparency to the health care market and reforming education to include more career and technical training ― are already in lockstep with those of this legislature.

And it if doesn't work out the way he planned, he'd be more than happy to come back to where he's most comfortable, he said: Running the family business.

"If you wanna make the case this is some type of navigation through a career in politics, I'd say you’re just reading it wrong," he said. "I think there’s better opportunity here to do more for Hoosiers. Some may say you’re job hopping. Well, that’s because they generally don’t like me anyway."

About Mike Braun

Age: 70

Home: Jasper, Indiana

Education: Wabash College, economics; Harvard Business School, MBA

Family: Wife Maureen, four children.

Previous experience: Indiana U.S. Senator 2019-24; Indiana state representative 2015-17; former president and CEO of Meyer Distributing.

Support from outside groups: Braun has endorsements from Trump, Club For Growth, Americans for Prosperity, National Troopers Coalition, Indiana State Police Alliance

Contact IndyStar state government and politics reporter Kayla Dwyer at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @kayla_dwyer17.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Career politician or business outsider? Why Mike Braun wants to be Indiana governor