The monuments controversy: Must heroes also be saints?

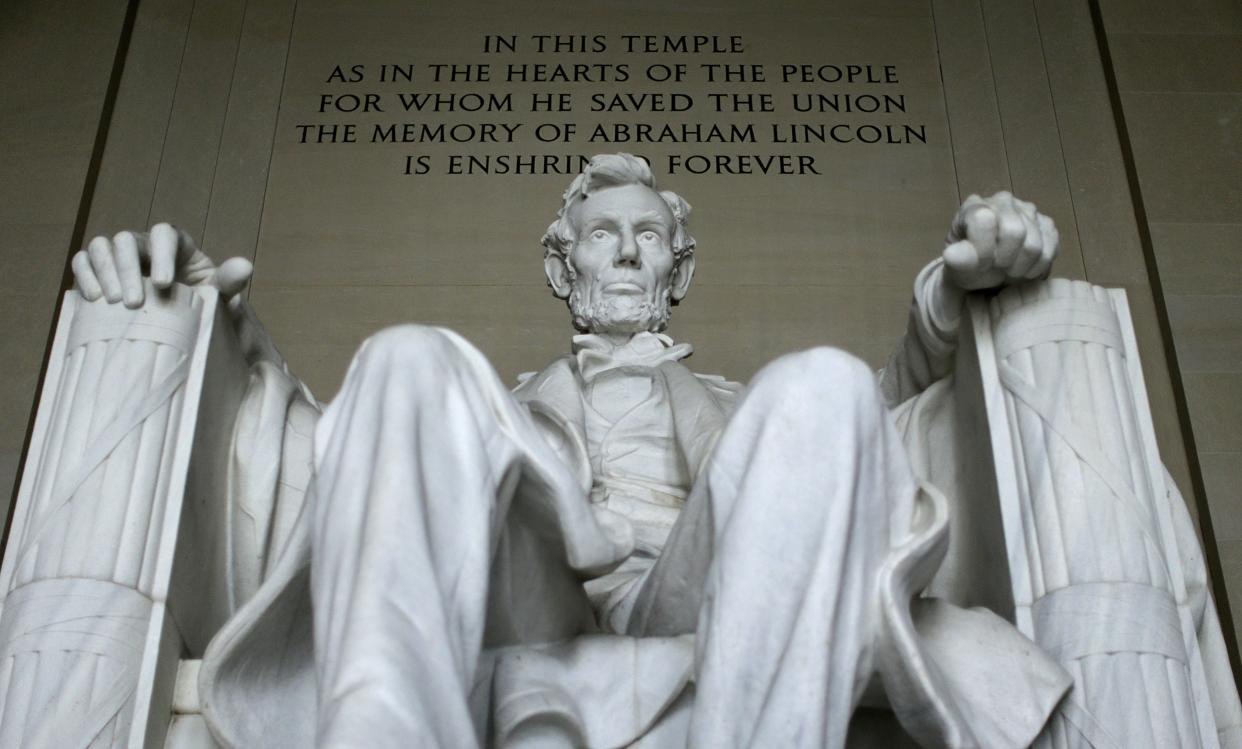

No one has ever counted them, but surely they exist by the thousands, in almost every state: statues, parks and buildings honoring a man who, in the years leading up to the Civil War, publicly proclaimed his belief that “there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.”

And who, as a white man, naturally expressed his sentiment “in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

The man was Abraham Lincoln.

This thought arises in the context of the debate over removing Confederate monuments in the South, and the warning, by President Trump and others, that this puts us on a slippery slope toward renouncing all the other heroes of American history who do not meet our current standards of political correctness.

Related slideshow: Here are the ‘beautiful’ Confederate monuments Trump wants to stay put >>>

Trump illustrated his point by reference to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who were slaveowners, but the principle can be extended almost indefinitely. New York, the world capital of reductio ad absurdum, will be a test case. Mayor Bill de Blasio has announced the creation of a task force to review the roster of historical figures honored in the city’s public spaces, with an eye to uprooting memorials that could be construed as “symbols of hate.”

Some of the candidates for history’s dustbin are already pretty obscure, including Horatio Seymour, a long-ago governor of New York whose portrait hangs near the mayor’s office in City Hall. Seymour ran for president, as a Democrat in 1868, with the unfortunate slogan: “This is a white man’s country.” A statue in Central Park honors the 19th century physician J. Marion Sims, the father of modern gynecology, who did his pioneering research on slave women, allegedly without their consent or the use of anesthesia. City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito has already called for the removal of the statue, which was defaced Friday night with spray paint. Few New Yorkers even know that a plaque in the sidewalk on lower Broadway honors the French general Philippe Petain, who received a ticker tape parade down the “Canyon of Heroes” for his exploits in the First World War but is remembered today primarily as a Nazi collaborator in the second.

But other monuments that may be up for review are among New York’s most famous civic symbols, including the statue of Christopher Columbus in Columbus Circle and Grant’s Tomb, honoring Civil War hero and President Ulysses S. Grant. Columbus, of course, has been a lightning rod for protest for years, partly for his treatment of the native people he encountered during his voyages, but also as a way of making a point about the centuries of exploitation that followed his discovery. Mark-Viverito has said she supports a review of the memorial to Grant, who is accused of anti-Semitism for an order he gave early in the war, which sought to curb black market trading in Southern cotton with the admittedly heavy-handed tactic of expelling Jews from several states under his army’s occupation.

And an online petition recently was posted seeking to return Roosevelt Island, in New York’s East River, to what is said to be its original Native American name of Minnehanonck. (The petition had only a couple of dozen supporters as of Sunday morning, but that was enough to warrant an article in the New York Post, which delights in tormenting political correctness.) The article notes that President Franklin Roosevelt, for whom the island was named in 1971, promulgated the infamous and inarguably racist order removing entire communities of legal immigrants and law-abiding American citizens of Japanese descent to internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

So how long will it be before the forces of iconoclasm turn their attention to that notorious racist Abe Lincoln — either sincerely or, more likely, as a way to subvert the campaign against Confederate monuments by carrying it to an illogical extreme?

In fact, there is a legitimate question here. When Trump made his point about Washington and Jefferson he was widely derided for missing the point, but in what way exactly? Most commentators pointed out that the two presidents were American heroes, while Robert E. Lee was a traitor to the United States. That distinction will do when the question is whether to honor Confederate generals, but not every case is going to break down as neatly. If the bright line is defined as broadly as “racism,” as currently understood, then, yes, Nebraska, we’re looking at you: Want to choose a new name for your capital city? What are we going to do with all the pennies (and nickels, dimes and quarters) in our pockets?

The answer must be this: to look at statues and other forms of civic honor in terms of their intent and overall message, not the biographical details of the life they commemorate. Washington, Jefferson and Grant — and for that matter Lincoln — held some views we now consider repugnant (and which, in the cases of Grant and Lincoln, were belied by their own subsequent deeds and words), but in the context of their own times they were heroes. If Washington and Jefferson lacked the moral vision to abjure slavery, it is a blot on their characters, but one they shared with most of their contemporaries. But by the time of the Civil War, you didn’t have to be a visionary to apprehend the monstrosity of enslavement. Upholding white supremacy was not just an incidental fact of Lee’s life, it was central to his place in American history, and the only reason there are statues to him at all. He isn’t being honored for what he did in the Mexican-American War.

This is not to say there won’t still be hard cases. You could, in principle, recognize Sims’ work in studying female anatomy while condemning his methods, but that would require an essay; a statue is a blunt statement, unsuited to convey nuance. If Sims hadn’t come up with a procedure to repair vaginal fistulas, someone else would have, and there’s a persuasive case that the cruelty of his methods outweighs his achievements. But it took Lincoln and Roosevelt, whatever their faults, to save the Union and preserve Western democracy. Saints, and statues of them, have their place. It’s called church.

Read more from Yahoo News: