Mummified brains show cocaine arrived in Europe far earlier than we thought

Indigenous communities in South America’s western regions have ingested coca leaves for both medicinal and recreational purposes for thousands of years. However, it wasn’t until 19th century Western chemists developed cocaine hydrochloride that the plant became popular across Europe. But thanks to new forensic analysis, at least some people knew about (and embraced) the coca’s effects as much as 200 years earlier than originally believed.

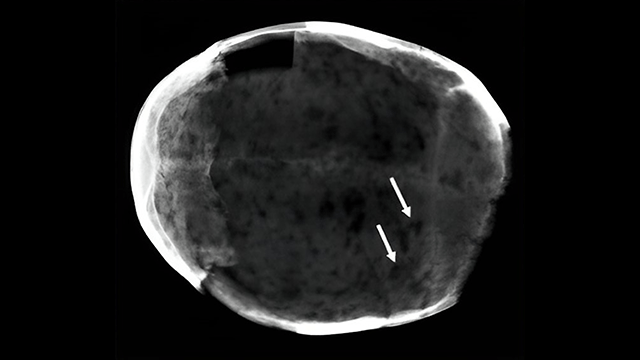

The evidence is detailed in a study published in the Journal of Archeological Science by medicinal and biomedical specialists at the University of Milan and Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda. According to the team, at least two preserved brains buried in a crypt near a 17th century hospital display evidence of the coca plant’s active components—cocaine, benzoylecgonine, and hygrine. These chemicals, particularly hygrine, indicates the pair of late Renaissance locals were either chewing on the leaves or ingesting a tea infused with coca shortly before their deaths and burials at Ospedale Maggiore.

[Related: Sharks are testing positive for cocaine.]

One of Italy’s most famous hospitals at the time, Ospedale Maggiore operated in Milan during nearly the entire 17th century. Almost a hundred years’ worth of medical care also meant plenty of deceased patients, requiring the construction and maintenance of an increasingly large crypt close to the medical facility. As the study authors explain, this ultimately resulted in an archeological trove that now contains an estimated 2.9 million bones from around 10,000 people.

The recovery and study of these remains continues to further experts’ understanding of the late Renaissance and early Modern eras. In 2023, for example, mummified brain and bone samples tested positive opium usage through the presence of Papaver somniferum (poppy seeds), as well as cannabis—the latter of which was previously undocumented for the time.

Coca was yet another plant once thought unknown to Italy until the 19th century, when pharmacists first began synthesizing cocaine hydrochloride salts. After an examination of the mummified brain matter from two people entombed at the Ca’ Granda, however, that narrative requires some alterations.

“[W]e present, to the best of our knowledge, the first hard evidence regarding the use of the coca plant in Europe through archaeotoxicological analyses on human remains in the extraordinary context of the Ca’ Granda crypt, hence backdating its use in Europe to the 1600’s,” the authors write in their paper’s conclusion.

This realization isn’t completely out of the blue. As the researchers note in their study, historical written evidence shows Spanish sailors were at least aware of the coca plant’s effects after arriving in South America. At the same time, Europeans soon grew increasingly interested in “exotic plants… in the New World” as knowledge spread throughout the continent. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, sea trade expanded between South America and Milan, then under Spanish rule. According to researchers, this demonstrates “a direct connection between the Italian city and the continent of origin of the plant.” That “direct connection” is now traced directly to the 17th century Ca’ Granda crypt—even though local pharmacological archives don’t report coca or cocaine for another 200 years.

Beyond the chemical trail, the study authors don’t currently know much more about how popular coca leaves were at the time, or if they used more for medicine or recreation. Given both the place and method of burial, however, experts believe the two bodies belonged to poorer people. Knowing this, it’s also possible that struggling, hungry residents may have turned to coca leaves for its appetite suppressing side effects. If so, the team hypothesizes coca leaves may not have only been present in Milan two centuries earlier than once thought—the plant may have been cheap, popular, and widespread, too.