Native people won the right to vote in 1948, but the road to the ballot box is still bumpy

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

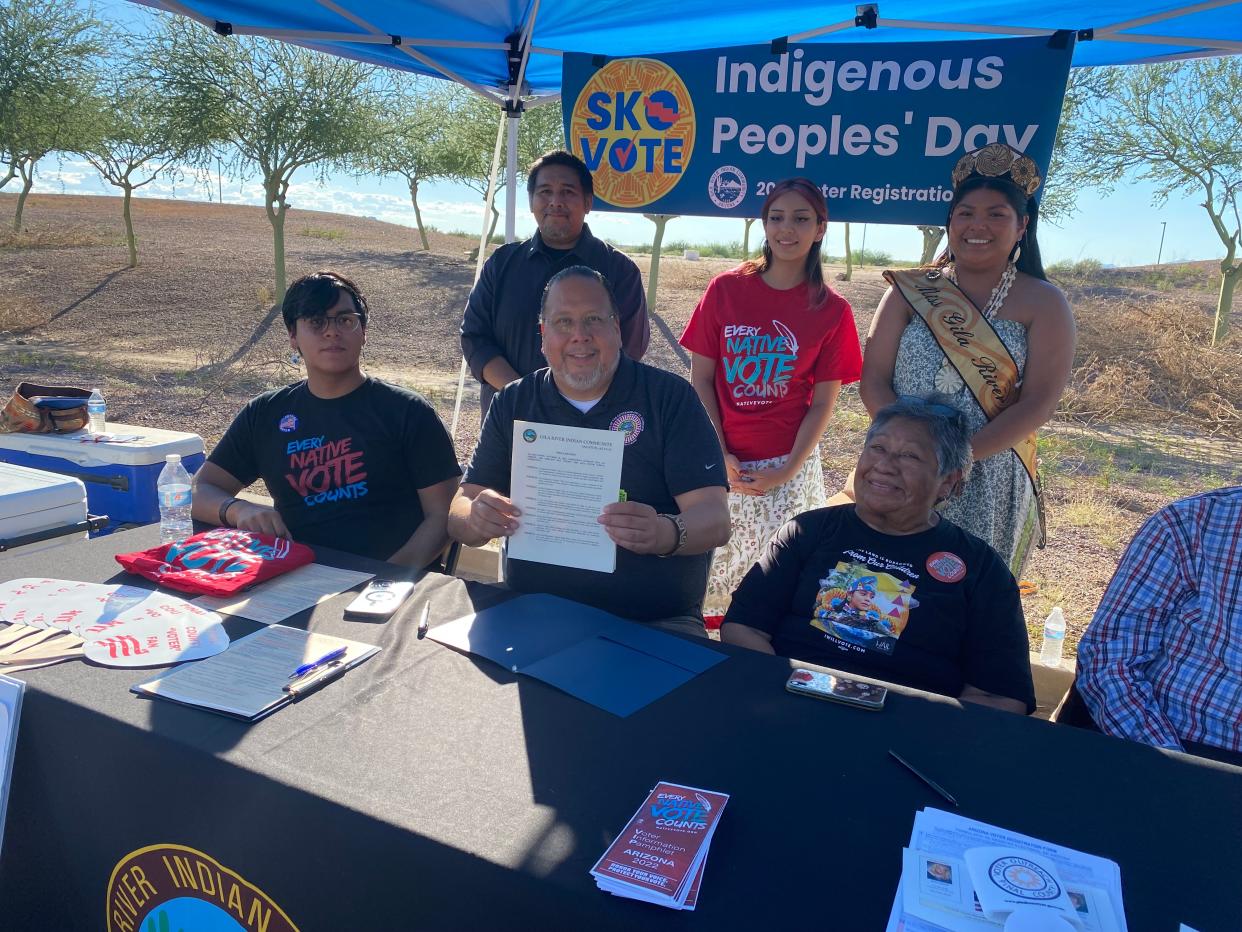

The Gila River Indian Community commemorated Indigenous Peoples' Day on Oct. 10 with a voter registration drive at its tribal administration building in Sacaton. Tribal members trickled in throughout a sultry late-summer afternoon to register or update their voter records at a Pinal County mobile voter outreach van.

The community helped with tribal elections and handed out information on where to vote and what to do if someone experiences attempts to suppress their vote.

At the event, Gila River Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis announced that Oct. 10, 2023, would be commemorated as "Peter Porter and Rudolf Johnson Day." Porter and Johnson were the first two Native people to use a nearly 100-year-old law extending U.S. citizenship to Native Americans to fight for the right of Indigenous people to vote in Arizona elections.

That fight, begun in 1924, failed at first. A second attempt in 1948 succeeded, yet it would be another 20 years before Native people had full voting rights.

Lewis' mention of Porter and Johnson and the decision to honor their work came at a time when many Native voting advocates fear that new barriers — including a ballot measure that would create new voter ID rules — are being erected to suppress the Indigenous vote.

Their history also underscores how Native Americans are still fighting for one of the basic American rights of citizenship: the right to vote.

Indian Citizenship Act paved the road to voting rights

Yavapai activist and intellectual leader Wassaja, also known as Carlos Montezuma, lay dying in a wikieup from tuberculosis in his home community at the Fort McDowell Indian Reservation in 1923, just as Congress was gearing up to finally extend U.S. citizenship to Native Americans.

One Indigenous history scholar said the efforts of Montezuma and other political and intellectual leaders paved the way for the passage of what became known as the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Until the passage of that law, American Indians were not considered U.S. citizens nor were they deemed eligible to vote, because the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the nation, excluded "Indians not taxed."

Through the writings and speeches of Montezuma and other members of the Red Progressives, a group of university-educated Native people who formed the Society of American Indians in 1911, the rest of the United States grew aware of the dire conditions Native people endured on and off reservations.

"It was those people who dedicated their lives to raising awareness across America that the reservation system under Indian Bureau management was not only a shambles, but it was violating the rights, the human rights, the citizenship rights of Indian people across the board," said David Martinez, professor of American Indian Studies at Arizona State University. "If not for people like Montezuma, America wouldn't know there was an Indian problem at all."

Martinez, who is of the Akimel O'odham and Hia Ced O'odham peoples and also has Mexican heritage, is the author of an upcoming book on Montezuma's importance in securing rights for Indigenous people, not only in Fort McDowell but throughout the nation.

Yet despite the success of those early activists, some states, including Arizona, continued to deny Native people the right to vote.

Tribal rights: Their pleas for water were long ignored. Now tribes are gaining a voice

Tribal members sue for their voting rights

The first attempt to rectify the injustice was in 1928, when Porter and Johnson, the two Gila River Indian Community members, filed an unsuccessful suit in the Arizona Supreme Court. They wanted the state to recognize voting rights for American Indians in Arizona, having been turned down when they attempted to register at the Pinal County Recorder's Office.

The tribe was the first to be recognized in Arizona in 1859, and had a history of doing business with the U.S. Army. Gila River was suffering through a decades-long period of dire poverty brought on by the loss of its water in the late 19th century.

The court ruled against Porter and Johnson because Indians were deemed to be under federal guardianship, which barred them from voting.

Twenty years later, two more Native men sued for their right to vote. Frank Harrison, a Fort McDowell Yavapai, was one of about 25,000 Native men and women who served in the U.S. military during World War II.

About 1,250 Indigenous people gave their lives during the conflict, but Harrison returned. He was hailed as a war hero, only to learn that his tribe was still mired in poverty. His elderly parents, denied Social Security and other elder benefits, worked hard just to survive and other tribal members lived in homes with no electricity or running water.

Harrison and Harry Austin, a fellow Fort McDowell Yavapai tribal member set their sights on casting their votes for leaders who would support their efforts to provide for their seniors and families.

The two went to Phoenix to register to vote, only to be turned away by Maricopa County Recorder Roger G. Laveen. From there, they went to the nearby courthouse and filed suit to overturn the 1928 decision.

On July 15, 1948, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled in the Yavapais' favor.

Arizona Supreme Court Justice Levi Udall wrote the opinion that affirmed Native people's right to vote.

“In a democracy suffrage is the most basic civil right, since its exercise is the chief means whereby other rights may be safeguarded," he said. "To deny the right to vote, where one is legally entitled to do so, is to do violence to the principles of freedom and equality.”

Language test put up new barriers

Despite the court's decision, Indigenous people continued to face barriers to casting their ballots. The state's next tactic was to impose English literacy tests on Native voters, according to a 2015 paper published in the Arizona State Law Journal written by ASU law professor Patty Ferguson-Bohnee.

Since only about 10 to 20% of Native voters were proficient in reading and writing their names in English, that rule eviscerated the Indigenous vote.

The restriction was not removed until 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a federal law enacted two years earlier that prohibited literacy tests.

By then, the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 had also strengthened tribal members' voting rights. The law bars election policies that deny or restrict voting because of race or membership in a minority language group.

A 2006 amendment to the voting act required the translation of election materials for people who have limited English proficiency. It also extended the Attorney General’s authority to send federal observers to monitor elections to prevent efforts to intimidate minority voters, Ferguson-Bohnee said.

In 2013, the provision of the Voting Rights Act that required the U.S. Department of Justice to "pre-clear" state voting laws and policies to avoid discriminating against voters of color was removed by the Supreme Court.

A 100-year-long struggle for Native voting access continues

Even after court decisions and legislation, tribal members in Arizona continue to hit roadblocks on the road to their polling places.

"I think people don't realize how much effort it takes for someone to participate in elections," said Ferguson-Bohnee, director of the Indian Legal Clinic at ASU's Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law and a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe.

Tribes have had to contend with newer challenges like a voter ID law, enacted in 2000, that has created the biggest challenge for Indian voters in the past decade.

Evidence of how the law suppresses Native voters was apparent when a Navajo weaver was turned away from a polling place in 2006. Agnes Laughter had no photo ID and no other documents to prove her residency. Born in a hogan, Laughter had no birth certificate, didn't drive, had no electric or water service at her home in the Navajo Nation and paid no property taxes.

Finally, Laughter was able to obtain a delayed birth certificate, but the Arizona Motor Vehicle Division rejected that. It wasn't until Ferguson-Bohnee went to the office and showed workers that the certificate was acceptable under the law that Laughter got her state ID and could once again vote.

Laughter later filed a lawsuit that proved pivotal in a larger action in 2008 that saw the Justice Department issue a directive that expanded what documents voters could use for identification.

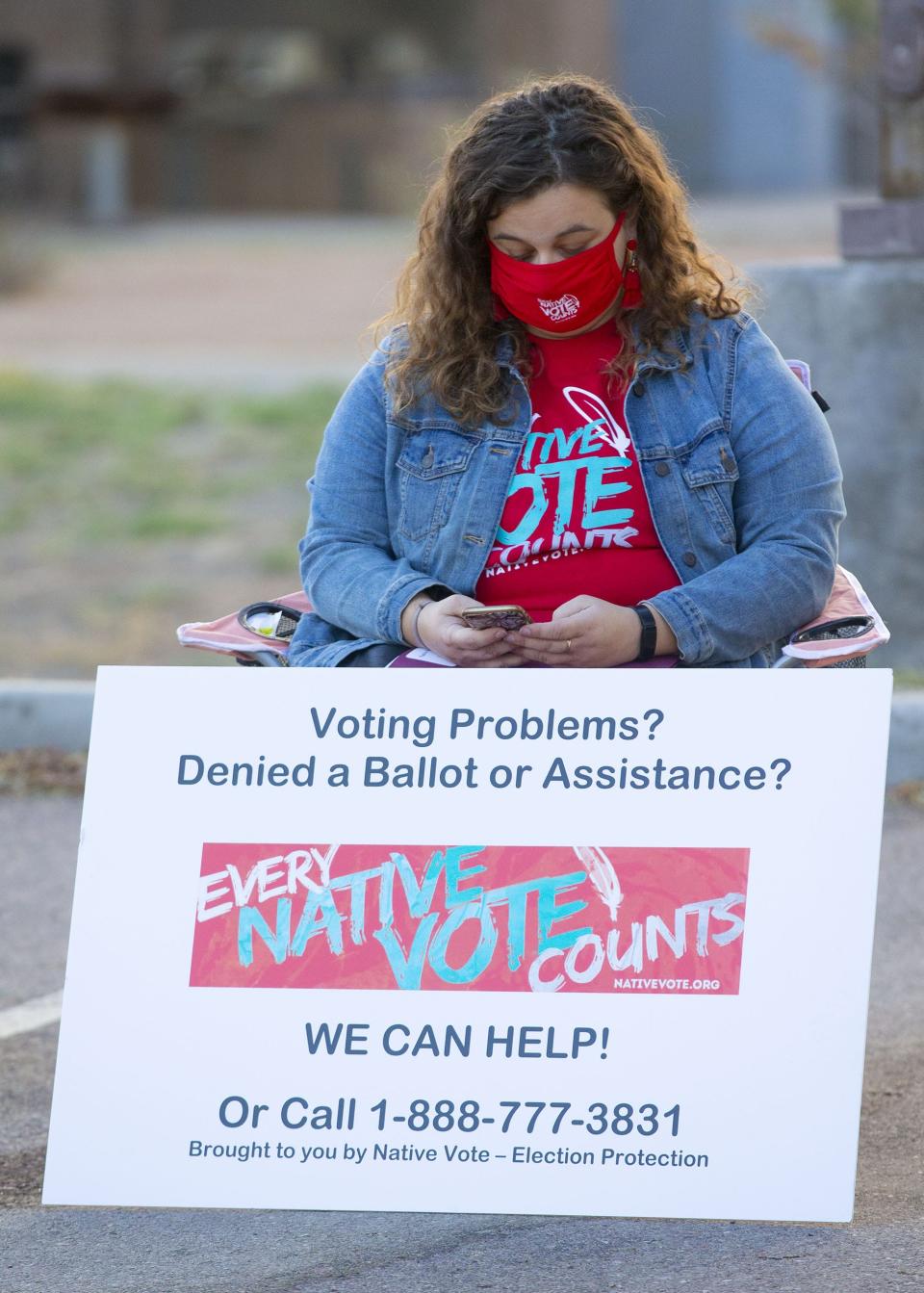

Ferguson-Bohnee now directs the Arizona Native Vote Election Protection Project organized by the Indian Legal Clinic. The project deals with issues ranging from voter registration, voter ID, provisional balloting, voters being turned away at the polls and voter intimidation.

Martinez, a member of the Gila River Indian Community, said obtaining rights such as voting was ultimately about the rights as people and tribes within the American political system.

"We got tired of being disparaged and ignored," he said.

Native people will always struggle to get their communities, nations or peoples recognized as part of the discussion, Martinez said. One big issue: the U.S.-Mexico border.

"Virtually everyone running for public office, certainly for governor and senator, they're expected to have something to say about the border and border security and immigration," Martinez said. "But not too many of them will realize, let alone have something meaningful to say about the fact that that border cuts across the Tohono O'odham Nation."

He asked why candidates are not talking about that issue: "Why do we all have to struggle to get their attention on important policy issues like this?"

'Our votes should be counted'

At least one Arizona lawmaker said he understands what Martinez is talking about.

"We want to make sure the voice of every American is heard because it's the foundation of our country," said Rep. Tom O'Halleran, D-Arizona, who is running in the newly created Congressional District 2. The district contains 14 of the 22 tribes in Arizona, two more than his current district. O'Halleran said he has visited every tribal community, including the Havasupai Tribe in the Grand Canyon, in his three terms in Congress and during the current election cycle.

"Each and every tribal member is a citizen of the United States," he said, "and it's not anything other than making sure people can participate and have their voice heard by their government and the people who represent them."

He also pointed to the House's passage of the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021.

O'Halleran's Republican opponent for the Congressional District 2 seat, Eli Crane, did not respond to a request by The Arizona Republic to discuss his stance on Native voting rights.

Some voting rights advocates said newer legislation and voter initiatives threaten to disenfranchise tribal members' votes after Native voters participated in large numbers during the 2020 election.

"Voter suppression has been happening forever really," said Allie Young, a Navajo Nation citizen who heads up the Indigenous education and advocacy group Protect the Sacred.

In addition to educating voters and advocating for better access for Indigenous communities, Protect the Sacred has led several rides through Monument Valley to raise awareness of how remote Navajo and other Native communities are, and why they work to get polling places and ballot drop boxes closer to where Native people live.

When Native people show up and vote, Young said, "we will elect leaders who will pay attention to this issue, who will change policies and enact solutions that will increase our opportunities."

The effort to suppress the Native vote has been ongoing, said Young, but, "as the first peoples of this land, our votes should be counted."

If you experience issues in casting your vote, visit the Arizona Native Vote Election Protect Project or call 1-888-777-3831.

Debra Krol reports on Indigenous communities at the confluence of climate, culture and commerce in Arizona and the Intermountain West. Reach Krol at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @debkrol.

Coverage of Indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and commerce is supported by the Catena Foundation.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: How Native people fought for the right to vote in Arizona elections