What does Neil Gorsuch's book on suicide reveal about his philosophy?

Within hours of Judge Neil Gorsuch’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, a statement calling him a “threat to patient-centered health care for millions of Americans” went up on the website of Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group “working to improve care and expand options for the end of life.”

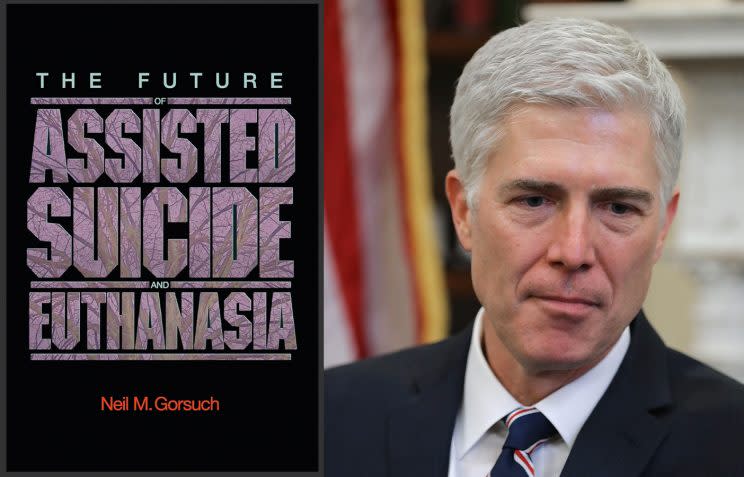

The “options” it wants to expand are for terminally ill patients to obtain a lethal dose of barbiturates to take if and when they decide to die. This is an issue on which Gorsuch is an expert, as the author of a book on the subject, an essay on constitutional law and moral philosophy titled “The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia.” To save time for the senators who will have to vote on his confirmation: He doesn’t care for the idea.

The issue may not have a lot of current salience at the Supreme Court; a 2006 ruling basically said the states can decide this question for themselves, upholding Oregon’s first-in-the-nation law on physician-assisted dying. Five other states — Washington, Montana, Vermont, California and Colorado — have passed similar laws, and there are bills pending in at least 16 others. In Vermont, a suit seeks a religious exemption for doctors from the requirement to inform terminally ill patients of their “end-of-life options.” Compassion & Choices is opposing the suit, although it is undoubtedly a long way from reaching the Supreme Court.

But C&C’s director of legal advocacy, Kevin Diaz, is already worried. Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion in the 2013 Hobby Lobby case, holding that businesses could refuse on religious grounds to pay for contraceptive care for their employees. “A judge who is willing to allow others, including corporations, to impose their religious beliefs on individuals making personal health care decisions at the end of life would be a dangerous addition to the nation’s highest court,” Diaz says.

The crux of Gorsuch’s argument, which he pursues through thousands of years of Western philosophy and centuries of American jurisprudence, is summed up pithily in his first chapter: the idea “that all human beings are intrinsically valuable and the intentional taking of life by private persons is always wrong.”

The phrase about “private persons” is crucial; it allows him to pursue his argument without grappling with the morality of the death penalty — or, for that matter, war. So is the word “intentional;” he allows that a doctor or family member may honor a terminally ill patient’s wishes to stop receiving treatment, as long as the intent was to stop suffering, and not to hasten death — even if death was the certain result. (In an aside that should reassure the National Rifle Association, he uses a similar line of reasoning to argue that “the gun shop owner who sells a gun is likewise absolved from being his brother’s keeper.”)

In fact, there’s more agreement here than perhaps meets the eye. Gorsuch’s title refers to “assisted suicide and euthanasia,” but those are mostly straw men in the context of the debate, at least in the United States. (European countries such as Holland and Belgium see things a little differently.) Euthanasia — killing someone without his or her conscious request and assent — is widely regarded as immoral and is illegal almost everywhere. Nor do states as a rule permit “assisted suicide” for people who just want to end their suffering, mental or physical.

Compassion & Choices is fighting for what it calls “medical aid in dying,” which means the provision of lethal drugs to people who are, in fact, dying, typically with a life expectancy of six months or less. Many — a third to a half, by some estimates — never even take the pills. Just having the pills in their possession provides comfort.

Gorsuch’s position here might seem like boilerplate conservative thinking; certainly it would resonate with the religious right, although Gorsuch himself is a mainstream Protestant Episcopalian. And his argument is directed, in part, against another well-known conservative judge who has appeared on many shortlists of potential Supreme Court nominations, Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit. Posner, whose political views tend toward the libertarian, has argued in favor of permitting some form of assisted suicide. But he has also, uncharacteristically for a judge originally appointed by President Ronald Reagan, upheld in some recent rulings a right to abortion.

Is there a correspondence between how a justice might view “medical aid in dying” and abortion? Last fall, in assessing President-elect Trump’s list of possible Supreme Court nominees, National Review approvingly quoted a blurb for Gorsuch’s book that said it “builds a nuanced, novel, and powerful moral and legal argument against legalization [of assisted suicide and euthanasia], one based on a principle that, surprisingly, has largely been overlooked in the debate — the idea that human life is intrinsically valuable and that intentional killing is always wrong.”

“Gee,” the magazine went on to speculate, “might that principle have any application to abortion?”