The neo-Nazi has no clothes: In search of Matt Heimbach's bogus 'white ethnostate'

LANCASTER, Ohio — Matt Heimbach, the 26-year-old founder and head of the grandly named Traditionalist Worker Party, has been called, in a headline in the Washington Post, “the next David Duke.” He is a key figure in the new white nationalist movement that has riveted media attention over the past year, but unlike the former Ku Klux Klan leader, whose appeal was concentrated in the South, Heimbach is planting the seeds of his movement along the back roads of the rural Midwest, in the small cities that have been left behind by deindustrialization and devastated by opioids.

Unlike many of his comrades on the so-called alt-right, who generally prefer to advocate for white nationalism from behind the protective shields of computer screens and fake names, Heimbach understands the value of media optics. His ability to articulate even his most abhorrent and offensive views in a disarmingly benign-sounding way has attracted the attention of the national media and drawn warnings from groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Huffington Post, among others, named him as one of the key figures behind the inscrutable movement of racists supporting President Trump, and someone whose larger political ambitions should not go unnoticed.

During the 2016 presidential primaries, Heimbach was caught on video shoving a black woman at a campaign rally for Trump in Louisville, Ky. Similar stories surfaced a couple of months later, after a Sacramento, Calif., rally held by members of the TWP and their California-based affiliates the Golden State Skinheads erupted in violence, leaving 10 people injured. Though Heimbach wasn’t at the event, national news outlets such as NBC News seized the opportunity to spotlight “the white nationalist behind violent California rally,” broadcasting Heimbach’s own claim that “he is not racist, but is merely calling for America to pay more attention to poor and working-class whites.”

As head of a white nationalist political party that is aligned with other neo-Nazi and separatist groups, Heimbach has shown a remarkable ability to win media attention for his program of organizing working-class youth to bring about his dream of a white ethnostate in the heart of the United States.

Taking notice of his ambitions is one thing; the question I sought to answer is how seriously to take them. “The next David Duke” sounds scary until you realize that Duke’s own political career peaked when he won a special election to the Louisiana state House of Representatives in 1989.

Among the most glaring problems plaguing this population — and perhaps the ripest for exploitation — is the deadly opioid epidemic.

“If our people die, it doesn’t matter if we have a heritage if they don’t have a future,” Heimbach said, describing a plan to attract broader support by tackling the opioid crisis at both the corporate and the personal level, calling for criminal charges against businesses that distribute OxyContin and similar drugs, and by helping individual addicts. “One of the things we want to be able to do is to get people who have suffered from addiction. We will not be silent as our people suffer and as our people die.”

It’s part of an ambitious program of job training, prison outreach and environmental activism that he describes in glowing, sweeping terms, a catalogue of social improvements he wants to bring to the downtrodden members of the working class — at least the white ones — to enlist them in his grand scheme of building a new nation founded on white identity.

I spent several months last year pursuing Heimbach, trying to learn more about his program for community outreach and see it in action. But it turned out to be far easier to get him to talk about plans than to actually demonstrate them. Heimbach is hoping to translate the online fervor that has fueled the recent rise in white nationalism into a real-life political movement, but I never met more than 10 followers at one time. And with each meeting that was changed, moved or canceled, I became more and more convinced that their activities amounted to little more than political “LARPing,” a gamer term frequently used by Heimbach that stands for “live-action role-playing.”

Heimbach repeatedly insisted that he’d be happy to introduce me to members of the Indiana chapter who’ve been struggling with opioid addiction, or let me tag along on a door-knocking excursion, like the one he said the group had recently conducted in Beattyville, Ky. — the country’s poorest majority-white town — to assess local needs for a winter coat drive. And yet, opportunities to actually witness the TWP’s outreach seemed to keep getting postponed or sidelined as Heimbach crisscrossed the country by car in pursuit of more public demonstrations.

One early attempt to observe their outreach back in September fell through when Heimbach instead offered an “exclusive” on his upcoming meeting with the leader of the Russian imperialist movement in Washington, D.C.

After I explained that my priority was to cover the grassroots organizing efforts, Heimbach told me about the TWP’s plans for a week of organizing in Tennessee during the first week of November in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Heimbach’s politics aren’t easy to fit into the usual left-right spectrum; he is a self-proclaimed revolutionary and a socialist in the National Socialist — i.e., Nazi — mode.

I could come a day or two early to meet with some of the regional coordinators, Heimbach told me, tag along as they went door to door and talk to some local residents of the communities they were hoping to recruit. He promised to inform me as soon as an exact date and location had been confirmed, and that was the last I heard about any activity in Tennessee until I came across a tweet from the TWP’s account in late October promoting two back-to-back White Lives Matter rallies in the towns of Shelbyville and Murfreesboro that coming weekend (Halloween). The rallies were being held by several white nationalist organizations, including the Traditionalist Worker Party.

Was this part of the week of organizing he had mentioned? I asked Heimbach. “Yep!” he replied. “We’re doing a sustained investment in the region.”

If there were any plans for community engagement beyond those rallies, they were either abandoned or kept under wraps.

After hours of standing in the cold while police waved each individual rallygoer through a metal detector at the event in Shelbyville — where the standard white nationalist fodder was barely audible over speakers blaring Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech from the counterprotesters across the street — I drove 40 or so miles to Murfreesboro to find that no one from the TWP nor any of the other groups in attendance had even bothered to show up at the second event.

Heimbach was back on the road the following day, heading home to Indiana before flying off to Europe to speak to a nationalist group in the Czech Republic.

Heimbach takes an expansive view of his place on the world stage. He’s established ties to nationalist groups from other countries, like the Russian Imperial Movement, the Czech Workers’ Party, and Greece’s far-right nationalist party Golden Dawn. In 2015, he was personally banned from entering the United Kingdom for promoting neo-Nazi and segregationist views. He seems eager to attend any and all events that promote his ideology, from the annual Stormfront summit in Tennessee; to a meeting of the Aryan Terror Brigade, a small, racist skinhead group; to picketing outside the W--hite House alongside Richard Spencer.

In 2016, Heimbach teamed up with Jeff Schoep, commander of the neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement, to form the Nationalist Front, a coalition of white nationalist groups. Members of the alliance organized rallies in Pikeville, Ky., and Shelbyville, Tenn., last year, and attended the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Va. Other prominent member organizations include the segregationist League of the South and Vanguard America, the white supremacist and neo-Nazi group with which James Alex Fields was seen marching in Charlottesville before he was arrested on murder charges for allegedly driving into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing one and injuring dozens of others. Vanguard America has denied any affiliation with Fields. Heimbach told me he’s been trying to get in touch with Fields, who is currently being held in Charlottesville’s Albemarle County jail, along with a handful of other young men — described by Heimbach as “political prisoners” or “POWs” — who’ve been arrested on assault charges stemming from the violent clashes at the rally. Though Heimbach said he doesn’t know Fields personally, he wants to contact him to “let him know he’s not alone.”

Related Slideshow: Violent clashes erupt at ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville, Va. >>>

Heimbach sees himself as standing in a long tradition of revolutionary figures, citing as influences international groups like the Irish Republican Army and Hezbollah, the militant Islamist group that gained political power in Lebanon through providing social services, as well as figures from American history such as Huey Long, the populist Louisiana politician who rose to national prominence during the Great Depression by appealing to Louisiana’s poor and working class, and Father Charles Coughlin, the “radio priest” of the 1930s who presaged today’s talk radio. Originally an advocate for social justice, Coughlin later turned his broadcasts into a forum for attacking Jews, Communists and Wall Street.

“We are an independence movement,” Heimbach explained. “We believe that Washington, D.C., is an illegitimate empire that we don’t want to be a part of, so we’ve got an official party position much like the Irish Republicans, of abstention. We will run people for federal office, but we would not take our seats if we were to win, because that’s legitimizing the power structure that’s keeping us in bondage.”

Though the trip to Tennessee had turned out to be a bust, Heimbach continued to maintain that he was eager to let me see the party’s outreach activities for myself. And so I continued to press him, until finally — after returning from yet another jaunt to D.C. to join Richard Spencer, Mike Enoch, and other white nationalists in front of the White House to protest the Kate Steinle verdict — he invited me to Paoli, the small, southern Indiana town where Heimbach lives on a compound of sorts with his wife and two young sons, his father-in-law and TWP co-founder Matt Parrott and a few other comrades.

I should come to Paoli on Friday, Heimbach said, so I could meet Parrott, who would give me a behind-the-scenes look at the group’s community organizing operation in southern Indiana, including job training and addiction outreach, and introduce me to some of the people who’ve actually benefited from these programs.

From Paoli, the plan was to drive east to some as-yet-undetermined location in Ohio, where Heimbach would be joined by several party members from the region, including the Ohio state coordinator, for a retreat that would involve, among other things, a training session on recruitment, followed by door-knocking and a night of camping — weather permitting. While I was more than welcome to observe these events, there were a few activities on the agenda, such as tactical training and a discussion of the party’s ideology, to which I was expressly not invited. Still, Heimbach assured me that he had already lined up plenty of party members who would share with me their stories about how the TWP helped them learn a trade, find a job or overcome addiction.

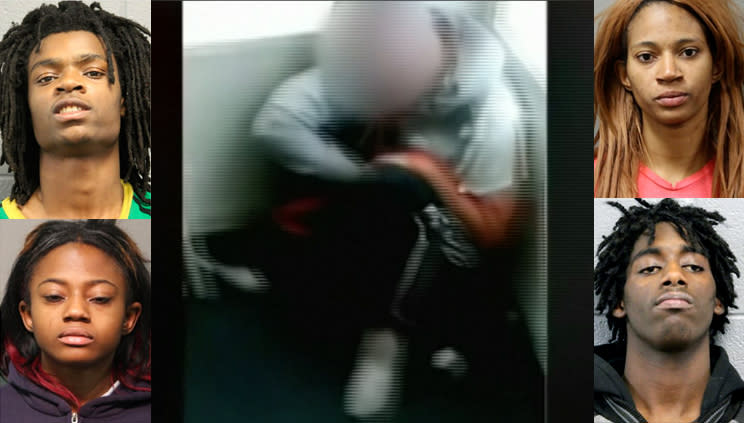

Just a day or two before I embarked on the journey to Paoli — which is about 60 miles from the closest major airport, in Louisville — Heimbach warned that the weekend retreat may be cut short so that he and his comrades could drive to Chicago that Sunday for a “flash demonstration” in Daley Plaza to protest a plea deal prosecutors had recently made with 19-year-old Brittany Covington, one of four African-American youths arrested last year on hate crime and kidnapping charges stemming from a disturbing Facebook Live video of the group abusing a mentally disabled white teen whom they’d apparently been holding captive.

The youngest and first of the four to be released from jail after nearly a year, Covington was sentenced to four years of probation, during which she is also barred from using social media — an insufficient punishment clearly motivated by race, in Heimbach’s view.

Nevertheless I set out for Indiana, and the weekend began like every other encounter I’ve had with Heimbach since I first interviewed him at Towson University in 2013: at a restaurant of his choosing — the location provided to me mere moments before we were slated to meet — where Heimbach arrived flanked by an entourage dressed all in black.

With his pudgy frame, round, bearded face and, until recently, glasses that were held together with adhesive tape, Heimbach seems like an unlikely leader of a racist movement hell-bent on dismantling the United States. But there is a darkness that belies his corny humor, and despite his polite demeanor and a slight Southern accent that was most likely not acquired during his childhood in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Poolesville, Md., he has a tendency to patronize.

The son of public school teachers whom he describes as Mitt Romney-style Republicans, Heimbach’s views on race and immigration were largely shaped by the nativist writings of Pat Buchanan, the right-wing ideologue and founder of the American Conservative magazine. By the time he entered college, Heimbach’s interest in Buchanan’s brand of paleoconservativism had led him to embrace other far-right nationalist thinkers, such as self-described “race realist” Jared Taylor. Taylor has long used his own magazine, American Renaissance, to promote widely debunked beliefs about the biological differences between racial and ethnic groups. (Heimbach met his wife at an American Renaissance conference.)

For his alternative outlook on world history, specifically Nazi-era Germany and the details of World War II, Heimbach draws heavily from the work of prominent Holocaust deniers like David Irving and Ernst Zündel.

In the handful of times I’ve sat down with Heimbach over the past five years, he has never once arrived alone. Heimbach may refer to those around him as “comrades” and members of his “family,” but before he even sits down at the table — with the others positioning themselves almost strategically around him — the hierarchy is obvious. Heimbach rarely makes an effort to introduce anyone, and just some of the men seem comfortable introducing themselves. The only one I recognize is Gunther, Heimbach’s 21-year-old bodyguard, from a previous meeting in Tennessee. Then he was quiet, with a blank expression that signaled either boredom or an attempt to look intimidating. This time, though, he was hand in hand with a young woman and decidedly more upbeat.

True to form, Heimbach led the table in prayer over chips and queso before proceeding to hold court, consuming at least one pot’s worth of free coffee refills while talking breathlessly about the scourge of immigration, multiculturalism and the impending demise of the American empire. For the most part, Heimbach’s acolytes were quiet, except to laugh at his jokes or to chime in occasionally when the conversation turned to something they’re all clearly passionate about, such as World War II and the “myth” of the Holocaust.

Attempting to keep the conversation on current events, I asked about a tweet that had been posted the week before from the TWP’s account (which has since been suspended) about Republican Roy Moore’s loss to Doug Jones in the Alabama Senate race. It read: “We had an elaborate undercover campaign throughout the entire state, just as we did with Trump. We fell short, but our members did an incredible job.”

Related slideshow: White nationalists and neo-Nazis stage ‘White Lives Matter’ rallies in Tennessee >>>

What was the “elaborate undercover campaign?” I asked.

“The media loves sensational stories,” he replied, making no apparent reference to Alabama. “If you tell a reporter 1,000 people are coming out for a demonstration, they’ll print that. You don’t really need to get 1,000 people to turn out for the demonstration.”

It was around this time I realized that notably absent was Matthew Parrott, who, based on the itinerary Heimbach had previously proposed, was the main reason for traveling to Paoli in the first place. And as Heimbach made himself comfortable, welcoming the waitress’s offer for yet another coffee refill, it became increasingly clear that there was no real intention of meeting up that night with Parrott, or anyone else for that matter.

I questioned Heimbach about the plan for the following day, and he told me they had booked a room at the public library in Vandalia, Ohio, near Dayton, from 9:30 a.m. to 11 a.m., where they would be discussing things like the TWP jobs program and cryptocurrency education — “Fiat money is so 2016,” Heimbach said. He told me later that the group was forced to move its fundraising to cryptocurrency because their credit card processing abilities were shut down after the Charlottesville rally.

The group would also engage in an ideological conversation during which, Heimbach reminded me, I would be excused but later given the opportunity to speak one-on-one with people who’ve benefited from the TWP’s outreach program.

The day was to culminate with a book burning on the property of someone who, Heimbach warned, is uncomfortable with media presence.

What about the door-knocking and community engagement, I asked. They’ll do that too, Heimbach said.

Vandalia is about a four-hour drive from Paoli, meaning we would need to be on the road by 5:30 a.m. But when my alarm went off at 4:30, there’d already been a change of plans.

“Our venue was compromised, just was made aware,” read the message Heimbach had sent me at 1:10 a.m. via Signal, an encrypted messaging service he’d been using exclusively to communicate with me. Heimbach uses the sort of language one might associate with a movie or video game character whose been tasked with a top-secret mission.

“My apologies, but sadly this comes with the territory,” he wrote, after explaining that the gathering was now being moved to “a backup venue south of Columbus, Ohio, at noon.”

It was the first in a series of cryptic messages and redirections I would receive from Heimbach and others throughout the ensuing day. The second came more than three hours after I requested an address for the new venue.

“Working on that now,” he wrote. Approximately 10 minutes later he sent another message: “Tony will have an answer at 9,” followed by a phone number with an Ohio area code. I had yet to meet or talk to anyone named Tony from the Traditionalist Worker Party, but wondered if Heimbach was referring to Tony Hovater, the subject of a recent controversial New York Times profile that, many critics said, read like a lighthearted attempt to normalize neo-Nazis.

Hovater, a co-founder of the TWP who, according to the Times piece, lives in New Carlisle, Ohio, was in fact the same Tony I’d been instructed to call, although I only learned that several hours later, when we finally met face to face. For now, he was just a monotonous voice on the phone telling me to stand by for an address, as he too was waiting to hear back from someone else who, he said, was “booking” the new venue.

At 11:20 a.m. I received a text message from Tony notifying me that the new plan was to rendezvous at 1 p.m. in the parking lot of a Walmart. From there, he wrote, “We’re going to follow a guy to a park.”

I made my way toward Lancaster, pulled into the crowded Walmart parking lot at about 10 minutes to 1 and checked my phone to find yet another message from Tony asking if I’d be OK waiting another hour. “We have a couple of people running late, including Matt,” he said.

Heimbach finally surfaced shortly after 2 p.m., accompanied by an entirely different entourage than the one he’d been with the previous night — including Tony, whom I immediately recognized from his photos in the New York Times, although now he was wearing a black jacket with the TWP emblem, a pitchfork inside a cog wheel, on his sleeve. Once again, Heimbach did not bother to introduce anyone else. The only woman in the group wore a hot-pink hoodie under her brown, bomber jacket and a floral scarf over her face, exposing only her forehead and eyes. She did not speak.

“These are the folks that were willing to be on camera,” Heimbach said, first suggesting that the official meeting, the one that was supposed to include outreach training and cryptocurrency education, would be held with a larger group later that day, then contradicting himself less than a minute later by telling me that the Ohio-based people had basically already discussed all that stuff earlier that morning.

“We just received our stand-down order for tomorrow,” said Heimbach, referring to the “flash demonstration” in Chicago. He did not elaborate on who, exactly, issues such orders, but it had apparently just been brought to his attention that Chicago’s Daley Plaza was currently occupied by the city’s annual German Christmas market.

I asked if that meant they would carry on with the original plan of going door to door in Lancaster or one of the towns nearby to introduce themselves to members of the community, to which he replied ambiguously, “We haven’t talked about that, actually, ’cause our plans have changed, like, five times.”

“Plans never survive contact with the enemy,” he continued, paraphrasing a theory of war attributed to 19th-century German Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke. “That seems to be the way with nationalist politics.”

And with that, the group piled into two cars, one leading the way to the park, the name or address of which no one was willing to share, and the other following behind me to make sure I didn’t get lost. Through the reflection in my rearview mirror, I could see Heimbach in the passenger seat behind me, sucking on an electronic cigarette, as I trailed the car ahead for about 20 miles, past acres of farmland and down a winding, narrow road through a wooded area until we reached a dead end at the entrance to the park.

The gate was locked, and I followed Heimbach and his posse over the short fence to a picnic table on the grass.

I sat down across from Heimbach and Hovater, and a few of the others filled in around us while the rest stood in a line behind the table, facing me. The woman had apparently been tasked with filming the encounter, and she held her phone with the camera pointed at me the entire time.

For the next hour I tried to extract some concrete evidence of the sophisticated social engagement and community outreach Heimbach had ostensibly invited me here to see.

The idea for this approach isn’t entirely original. “It’s not the first time a white supremacist has tried to do this kind of social-good stuff,” said Heidi Beirich, director of the Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center. At the same time, she said, “I’ve never seen a white supremacist group really do these things. They’ve said they were going to, but they haven’t really followed through.”

Ultimately, she said, “I guess it remains to be seen if Heimbach really intends to put his money and his time where his mouth is, right?”

Exactly. I’d been especially intrigued by Heimbach’s supposed plan to take on the opioid crisis as a legitimate issue impacting white working-class voters. But while he continued to make bold statements like, “The war on drugs could be won in, essentially, an afternoon if the United States government actually wanted to win it,” Heimbach offered little indication of how the TWP proposed to better solve this problem.

When I asked about the opioid initiative, he said, “Tony literally has anti-Big Pharma banners in his house for our next event.” Pressed for more details on how they actually planned to use the issue to mobilize support, Hovater stepped in, offering a plan that seemed to morph as he explained it, from working with local police to clean up dirty needles in neighborhoods with heavy drug use, to making a big show of calling on local police to clean up such neighborhoods while pledging to do so themselves once the authorities failed to meet their demands.

“The biggest thing is we need to be able to show our people what the system is unable or unwilling to do, because they could solve all these problems,” Heimbach declared. “If we can do it, then we show that we are more trustworthy than the police. This how we build a state within a state, where, in five years, 10 years, if you’re a white person in America, if you need something done in your community, you come to us first.”

It was hard to envision how the TWP planned to take on Big Pharma and solve the opioid crisis with a room full of banners and a pledge to clean up dirty needles from parks, and Heimbach himself admitted that funding has been the greatest obstacle to carrying out their lofty plans.

“Unfortunately, the ruble exchange rate is killin’ us right now,” Heimbach said, amusing himself with this characteristically cheesy yet subversive joke about the liberal outrage over supposed Russian interference in American politics.

Though Heimbach claims the TWP has close to 2,000 registered supporters (i.e., people who’ve signed up through their website to be on their emailing list), he says that only about 500 of them pay dues — both figures that are relatively impossible to verify but, based on the turnout at recent rallies, seem like they might be inflated.

Even if Heimbach’s estimates are accurate, 500 people paying $20 a month does not amount to a very big war chest, especially when a good portion of those funds seems to go toward transporting Heimbach and other comrades across the country to take part in various demonstrations, meetings, and speaking engagements. Heimbach and Hovater see great moneymaking potential in starting a welding business, which has yet to get off the ground. In the meantime, Heimbach points to the group’s Tennessee coordinator, who sells secondhand items on eBay, as an example of a TWP member who has figured out a way to earn an income.

Based on Federal Election Commission records, the TWP’s political fundraising arm has a long way to go before it will be able to compete with the hundreds of millions of dollars fueling the mainstream political parties.

According to public filings with the FEC, between July 1, 2015, and Dec. 8, 2016, the Traditionalist Worker Party National Committee raised a total of $11,551 and spent $12,733.

This, of course, was all before the TWP was forced to start soliciting bitcoins and other cryptocurrency after being shut out from mainstream fundraising platforms and credit card processors in the wake of Charlottesville. The party does seem to have gotten its 2018 fundraising off to a better start, however. According to the latest filings available from the FEC, the TWP National Committee raised a total of $9,286 from July 1, 2017 to Sept. 30, 2017. Though by comparison, the Republican National Committee took in more than $121 million during that same time period.

George Hawley, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Alabama and author of the recent book “Making Sense of the Alt-Right,” said that in his view the funding issue has always made the TWP’s community outreach plan seem “implausible.”

“In theory, the idea of gaining social support by providing useful services makes sense. That requires resources, however,” he said, noting that groups like Hezbollah and the Irish Republican Army, both of which Heimbach sites as influences for the TWP, “enjoyed significant financial assistance from the outside.”

“Perhaps Heimbach and his colleagues have some deep-pocketed sponsors that we don’t know about,” Hawley offered. “But it looks to me like a shoestring operation, and their members don’t appear to be doing any better financially than the people they would seek to assist.”

According to the FEC, 100 percent of donations to the TWP’s National Committee during the 2016 election cycle came from individuals, with the majority of “large” donors spending between $200 to $400 at a time (the maximum annual amount an individual can donate to a national party is $30,800). The party’s biggest single donation, a whopping $979, came from William Johnson, the head of the white nationalist American Freedom Party, who was selected by the Trump campaign to serve as one of its California delegates during the Republican presidential primaries. Johnson was ultimately removed from Trump’s list of California delegates after his white supremacist views were highlighted in the press, with the campaign blaming his acceptance on a “database error.”

Hawley went on to explain that, in terms of financing the broader white nationalist movement, the “TWP’s situation is not unique.”

“There are some wealthy people that support radical right causes that we know of, but they are few in number, and their contributions seem comparatively small,” he said. “There is no alt-right equivalent to the Koch brothers, so these groups are always strapped for cash.”

“We are not going to see a major alt-right think tank break ground in the Beltway anytime soon,” he continued. “Nor will the alt-right enjoy well-funded and well-organized grassroots groups equivalent to the conservative tea party.”

Until recently, ex-Trump adviser and Breitbart News chairman Steve Bannon was among the few alt-right figures who enjoyed the support of a wealthy benefactor, Rebekah Mercer. But even before Bannon was pushed out of his post as the head of Breitbart News following his break with Trump, Bannon’s plans for a nationalist revolution had already suffered several significant setbacks, including the loss of his candidate in Alabama, Roy Moore. The first major political fight in Bannon’s post-Trump war against the Republican establishment ended with the election of Alabama’s first Democratic senator in 25 years.

David Cunningham, a professor of sociology at Washington University and author of “Klansville USA: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan,” predicted that even if the TWP could make itself the voice of concern over the opioid epidemic, mainstream parties would co-opt the issue.

Groups like the TWP “tend to be more effective in their ability to call out and draw on discontent than they are to actually address any of these issues, in terms of any viable policy solutions,” he said. “Because, fundamentally, the only real base that these extremist groups have are people who see these issues through a racist lens.”

In fact, for all his talk of building community and advocating for the poor, forgotten white people in America, Heimbach made very clear that he is only interested in offering help to white people who are expressly committed to white nationalism.

“If someone was, like, anti-white and addicted to heroin, OK, not my problem,” he said. “We’d be cucking ourselves as a movement if we were going to be helping people that are opposed to the survival of our people.”

Both Heimbach and Hovater insisted that this attitude has limited neither their ability to raise interest in the movement nor to help people, repeating the same stories I’d heard before about the families they collected coats for in Kentucky, or the business owner from their North Carolina chapter who puts TWP stickers on hundreds of pounds of canned food each month and donates it to the local food bank, or the recovering addict in Indiana who now sponsors new members dealing with drug abuse. However, despite Heimbach’s repeated promises to introduce me to some of these people — or at the very least give me their names — the subjects of these supposed success stories never materialized.

The best he could offer was the testimonials of a few of the party members who’d accompanied him to the park, which really offered more insight into Heimbach’s own ability to influence certain vulnerable young men than the success of the party.

Zane, a baby-faced 18-year-old who declined to give his last name, talked about his journey from nationalist internet chatrooms to Charlottesville, where he met Heimbach and other TWP members and “ended up accidentally getting roped into … that wall of shields” pictured during the violent clashes with counterprotesters. He had such a “good time” being at the center of this chaos that he’s been actively involved with the TWP ever since, traveling around the country to participate in various other rallies and protests, and forgoing college in favor of learning how to weld at a technical training school the TWP hopes to build in Ohio.

“It doesn’t seem like it’s worth it to pay that much money to just get a degree that makes you the same as you would doing a normal, blue-collar job, like welding,” he said.

“And not be in debt the rest of your life,” Heimbach chimed in, adding that “Zane is a great example” of the people TWP is trying to target. “Eighteen years old, white kid, what are you supposed to do with your life, right? You don’t really have a lot of options.”

“Before TWP, I had no idea what was going on. No one was really there for me,” Zane continued. “But now … I can say I’m pretty confident I’m going to have a job welding and be living pretty good.”

Mark Semus, who is currently studying gunsmithing while between jobs, said he’s also eager to get involved in the welding program, “once it gets going,” and hopes that he could make a career of the trade. Semus came to the Traditionalist Worker Party about five months ago after previously being involved with another nationalist group. He said he was drawn to the TWP because it “seems to be one of the only nationalist groups that is thinking about the bigger picture, the workers, the gears of society that’s making it so this is all possible.”

Semus echoed Heimbach’s “us vs. them” language of community and family, saying his high school friends “didn’t really understand my views, so they kind of cut me off, and I found better friends.”

His family doesn’t support his beliefs either, Semus said, but “they don’t hate me for it. … Some people’s families have completely ostracized them.”

Heimbach, who says he hasn’t seen his parents since college, is one of those people.

“They told me I had to choose my politics or my family,” he explained to me after the rally in Shelbyville. “I’d rather just be normal,” he said. “I think all of us would rather just be normal. But I’m convinced that this is right.”

Either that, or he’s painted himself so far into a corner that he simply can’t back out now. Regardless, Heimbach is hardly the only one whose participation in this movement has come at a cost. At its core, the TWP is centered on the claim that American society has deprived young white people, men in particular, of the right to community and economic opportunity. But for an overwhelming majority of the group’s members I’ve talked to, it’s their affiliation with white nationalism, more than anything, that has resulted in alienation by family, friends and even employers.

As Hovater, who lost his job as a restaurant cook after the Times article, told me, “At some point you become unemployable in the movement.”

The sun began to set, and suddenly the crew at the park became eager to get moving. They had a book burning to attend — the one activity on the original agenda that managed to survive multiple changes of plans. I decided to give Heimbach one last opportunity to prove that there was more to the TWP’s outreach than what I’d seen so far, and asked him again if they were planning to go door-knocking at any point during the weekend.

“You guys wanna go door-knocking?” Heimbach asked, to no one in particular. “I’m down,” Hovater replied with a shrug. Tomorrow morning in Dayton, Heimbach offered, meet-up spot to be determined.

That was the last conversation I had with either of them. The next morning I drove to Dayton without a specific destination, calling both Heimbach and Hovater several times on the way, with no response from either. There was not going to be any door-knocking that day, and I was pretty sure there never was. On the way back from Dayton I received a call from Gunther, Heimbach’s bodyguard. He said was trying to reach Heimbach, who told him that a journalist was coming to visit their property in Paoli that day, but apparently offered few other details. Gunther thought he might have been referring to me and, since he hadn’t heard from Heimbach, was hoping I could tell him what time I’d be coming by.

Must be someone else, I told him, adding that Heimbach had actually ditched me that morning.

“Yeah, sorry to hear that,” Gunther said. “That’s prone to happen.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: