A new generation of anti-gentrification radicals are on the march in Los Angeles – and around the country

LOS ANGELES — The protest at Mariachi Plaza didn’t seem, at first, like a declaration of war.

In fact, the Feb. 7 event looked like the same sort of grassroots, anti-gentrification gathering that might have taken place in any big American city at any point over the past 10 years as higher-income transplants have increasingly colonized lower-income urban communities, remaking once marginalized neighborhoods in their own cold-brew-and-kombucha image.

But this one was different.

That’s because it was organized by Defend Boyle Heights, a coalition of scorched-earth young activists from the surrounding neighborhood — the heart of Mexican-American L.A. — who have rejected the old, peaceful forms of resistance (discussion, dialogue, policy proposals) and decided that the only sensible response is to attack and hopefully frighten off the sorts of art galleries, craft breweries and single-origin coffee shops that tend to pave the way for more powerful invaders: the real estate agents, developers and bankers whose arrival typically mark a neighborhood’s point of no return.

“Gentrification is not your next documentary topic,” the group recently wrote on its blog. Its leaders distrust the media, saying they’d “rather opt out and tell our story for ourselves,” and did not respond to interview requests.

“Gentrification is not a trend for the ‘woke wide web’ or for the detached subculture of the left to consume,” they continued. “It is a vicious, protracted attack on poor and working-class people. And we are engaging in class warfare that leaves our friends, families, and neighbors, homeless, devastated, deported or dead. So get with down friends and make s*** crack.”

By “making s*** crack” — by boycotting, protesting, disrupting, threatening and shouting in the streets — Defend Boyle Heights and its allies have notched a series of surprising victories over the past two and a half years, even as the forces of gentrification continue to make inroads in the neighborhood. A gallery closed its doors after its “staff and artists were routinely trolled online and harassed in person.” An experimental street opera was shut down after members of the Roosevelt High School band — egged on by a group of activists — used saxophones, trombones and trumpets to drown it out. A real estate bike tour promising clients access to a “charming, historic, walkable and bikeable neighborhood” was scrapped after the agent reported threats of violence. “I can’t help but hope that your 60-minute bike ride is a total disaster and that everyone who eats your artisanal treats pukes immediately,” said one message. The national (and international) media descended, with many outlets flocking to Weird Wave Coffee, a hip new shop that was immediately targeted by activists after opening last summer.

As a result, like-minded groups in other cities — Chicago, Austin, New York — have adopted the same hard-line tactics. Their ranks are small and their methods are controversial, even within the communities they purport to defend. But their members are drawn from the most politically radical, economically anxious generational cohort in recent memory — young millennials of color — and their cause has the makings of a national movement: a new, more militant war on gentrification.

***

Back at Mariachi Plaza, activists set up a long table and rows of folding chairs in front of a curved concrete stage. Black-clad skateboarders loitered on nearby benches, smoking; mothers pushed children in strollers. It was 6:30 p.m. The sun was setting. The avenues of Boyle Heights were quiet — a succession of low-slung brick storefronts with signs in Spanish (Birrieria De Don Boni, Deportes Prieto), Chicano murals from the 1970s, more recent graffiti art, and modest, pastel-hued bungalows behind low iron fences. Unlike in, say, Brooklyn, few obvious signs of gentrification intruded upon the largely working-class, largely Latino streetscape, despite at least a decade of warnings that Boyle Heights was on the brink of a big change.

Yet the plaza itself symbolized how that transformation might finally be underway: For the last year, dozens of the musicians who live in a nearby apartment building and gather there to look for gigs had been warring with their new landlord over steep rent hikes that would force them to move — an all-too-common fate in a neighborhood where more than 75 percent of residents are renters, and where the median monthly rent rose $600, from $1,950 to $2,550, between September 2016 and August 2017.

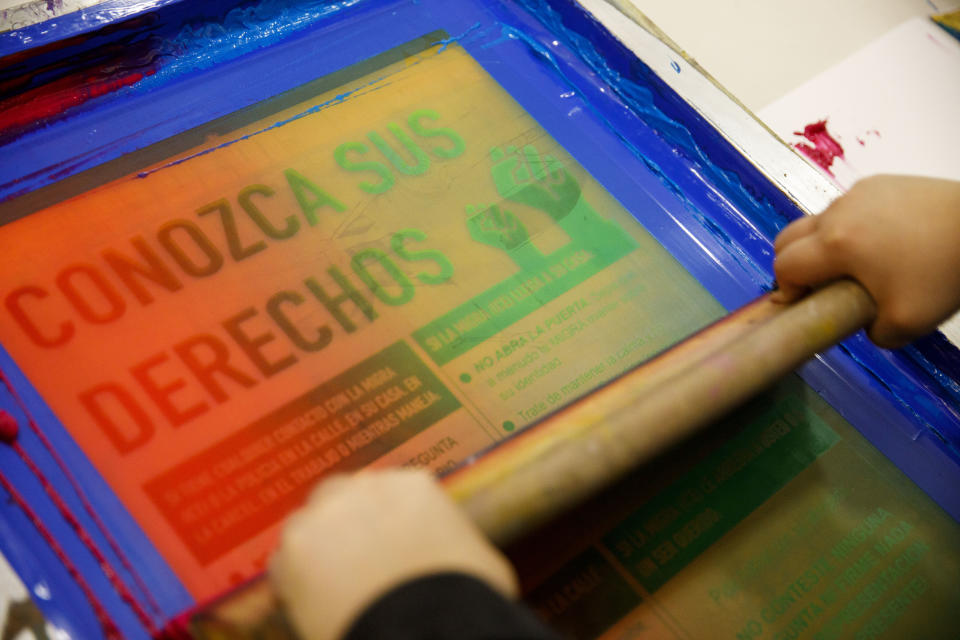

Soon, more activists began to meander into view. Some signed clipboards. Others bought T-shirts. A gray-haired woman in a loose hoodie passed out translation headsets; a man in rainbow suspenders distributed leaflets. The program began at 7 p.m.

There were four speakers: a mother of six who had won several court battles against the landlord trying to raise the rent on her East L.A. apartment; an organizer for the L.A. Tenants Union who urged listeners to support a proposed ballot measure that would overturn California’s major anti-rent-control law, a man who had led a recent rent strike at his building in Boyle Heights and an activist who spent every Sunday in Mariachi Plaza, handing out food and clothes to needy locals.

So far, familiar enough.

Yet throughout the event there were also hints that something less civil — and far more confrontational — was afoot. “F*** Hipsters,” read the shirts for sale. A few activists clutched bright red hammer-and-sickle flags. And behind the attendees stood silent men and women in black ski masks — “comrades,” said emcee Facundo Rompe, “who are here to protect us.”

Between speeches, Rompe — tall and lean, with the glasses, goatee and nom de guerre of a vintage leftist — took the mic and alluded to activities that might (or might not) transpire later that evening.

“Obviously I can’t tell you everything we’re going to do, because the cops have really big pig ears,” Rompe said as he gestured toward a pair of plainclothes officers watching from a silver car at the edge of the plaza. “But what I’ve found is that the only thing that works to stop gentrifiers is intimidation. The only thing that works is fear — the fear of harm. Because they are harming us.”

A few minutes later, the program concluded. Rompe made one last announcement.

“There’s a legal side to the struggle, and there’s a creative side to the struggle,” he said. “No one is telling you you gotta mask up — that you gotta be militant as f***. No one is telling you to do that — although,” he chuckled, “that is the right thing to do.

“So let’s take a poll,” Rompe continued. “Raise your hand if you’re anti-gentrification — and you’ll do whatever the f*** possible to stop it.”

Everyone in the plaza — about sixty people in total — raised his or her hand.

“So that means you’re down to put your body on the line?” Rompe asked.

He scanned the crowd; no hands fell.

“Cool,” he said. “Then let us show you a tour of Boyle Heights.”

***

Why are young people taking such a militant stand against gentrification? And why now?

Gentrification itself is nothing new. The term originated in a 1964 essay by Ruth Glass, a British sociologist writing about the displacement of working-class Londoners, and the transformative effect of such displacement on American cities has become one of the most well-known economic storylines of the early 21st century. In the 1960s and ’70s, cities were decimated by white flight, riots and the decline of manufacturing; in the 1980s, crime and drugs drove even more people away. But since the era of former President George W. Bush, major urban cores across the nation have been on the upswing, attracting millions of new residents. Neighborhoods from Fort Greene in Brooklyn to the Mission District in San Francisco have become wealthier — and whiter — in the process.

Anti-gentrification activism isn’t novel either. For decades, nonprofit groups nationwide — Chicago’s Pilsen Alliance, the East LA Community Corporation — have pushed back, working to rally residents around affordable housing initiatives and secure a voice in the planning process.

But Defend Boyle Heights and its ilk aren’t publishing white papers or dialoguing with developers. They are fighting in the streets.

So what’s changed?

The first thing is income inequality — “the defining challenge of our time,” as former President Barack Obama once put it — and its effect on cities in particular.

In 2016, the top 1 percent made 87 times more than the bottom 50 percent of workers, up from a 27:1 ratio in 1980, and CEOs made 271 times more, on average, than a typical employee — a 930 percent increase since 1978.

And it’s not just the 1 percent. In fact, the recent growth of the upper middle class may be even more consequential. According to a 2016 report by the Urban Institute, households with incomes of $100,000 to $350,000 made up about 13 percent of the population in 1979. Today they make up nearly 30 percent. The $100,000-plus crowd is dominating America’s economy.

They’re also clustering in cities. According to a December 2017 study from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, in San Francisco, a whopping 93 percent of new renter households between 2006 and 2016 — along with 65 percent in New York City — earned more than $100,000 a year. New rental apartment construction followed the money into cities, catering increasingly to the top end of the market, while overall the renter population remained younger with lower incomes than homeowners. Meanwhile, thanks in part to the post-economic-crisis crash in minority home-ownership rates, the overall renter population is heavily minority — 47 percent — and more likely to contain immigrants.

At the same time, poverty has been on the rise — and is hitting cities especially hard. Earlier this year, a United Nations special rapporteur concluded a 15-day investigation that discovered poverty and inequality in the U.S. at levels “shockingly at odds with [the United States’] immense wealth and its founding commitment to human rights.” Today, 1.5 million American households live in extreme poverty — nearly twice as many as 20 years ago.

The result is that major American cities have become economically polarized — playgrounds for the six-figure set, and increasingly perilous footholds for the poor, with almost no middle class left in between. A recent analysis from the National Housing Conference and the Center for Housing Policy showed that neither a teacher nor a social worker making the median national salary in their respective professions can afford the fair market rent for a two-bedroom home in the Boston, San Francisco, San Jose or Washington, D.C., metro areas. In San Francisco, the annual income now required to purchase a median-priced home is $303,000; in Las Vegas, nearly 9 out of 10 of the poorest renters spent more than 50 percent of their income on housing (a burden described in official reports as “severe”).

These are just some of the factors that led the Harvard study authors to conclude that the rental markets in America’s largest cities are “settling into a new normal where nearly half of renter households are cost burdened.”

The urban real estate market is the clearest, and most brutal, expression of this inequality — and big money is only making matters worse. The aesthetic and culinary choices of hipster millennials and Gen X parents may be the public face of gentrification, but behind all that avocado toast is a slew of changes driven by companies and holders of major capital.

Developers — often aided by the politicians they donate to — have concentrated on building homes and apartments for six-figure arrivistes, not the working-class locals they threaten to displace.

A new wave of foreign investors has also looked to the revived American city as a moneymaking opportunity. At the start of the decade, foreign investment in the New York real estate market hovered under 20 percent; by 2016, it had skyrocketed to 50 percent. Not to be outdone, Los Angeles just tied N.Y.C. for the first time as America’s top city for foreign buyers, according to a 2017 poll of major investors.

The rise of Airbnb, meanwhile, has transformed everyday homeowners and even tenants into bed-and-breakfast proprietors, ratcheting up rents in quickly gentrifying areas. According to a study by McGill University researchers, Airbnb has pushed up New York rents by as much 7 percent, with the biggest disparity in returns between white hosts and minority ones coming in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and Harlem. Today, newcomers aren’t just moving in as families; they are moving in as cottage businesses.

And it’s not just the economic conditions in cities that have changed. The political attitudes of young, lower-income, largely minority residents have also changed in response.

Millennials are, simply put, “facing the scariest financial future of any generation since the Great Depression,” as HuffPost’s Michael Hobbes recently put it. They’ve taken on at least 300 percent more student debt than their parents did. They’re about half as likely to own a home as young adults were in 1975. One in five is living in poverty. Based on current trends, many of them won’t be able to retire until they’re 75. Jobs have become gigs; college is exorbitant, starting salaries are paltry the social safety net is shredded.

And all of these trends are especially acute among the poorer, nonwhite millennials who tend to live in major cities. Between 1979 and 2014, for instance, the poverty rate among young high school-only graduates more than tripled, to 22 percent, and roughly 70 percent of black families and 71 percent of Latino families don’t have enough money saved to cover three months of living expenses.

These harsh realities aren’t lost on millennials of color — especially young men and women from gentrifying neighborhoods, where such inequities tend to be on vivid, daily display. To that end, a 2016 Harvard Institute of Politics poll found that only 42 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds now support capitalism; a third now identify as socialists. Among those who backed Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy, the number was even higher — a full 54 percent — and minorities and people without a college degree were more likely to support socialism as well.

The rise of America’s first developer-in-chief, meanwhile, has fanned the flames, creating an atmosphere of at-all-costs resistance on the left — and a newfound sense of political urgency among women and people of color, who feel particularly unwelcome in Donald Trump’s America.

Ultimately, the fight over gentrification is what the fight over income inequality in America looks like up close today: a clash between the economic forces transforming our cities and a young, diverse, debt-saddled generation that is losing faith in capitalism itself.

Not so long ago, activists sought to occupy Wall Street. Today they want to occupy the streets where they live — and where they fear they won’t be able to live for long.

***

It was nighttime now in Boyle Heights. A few minutes after Facundo Rompe issued his invitation, a core group of activists embarked on his tour. Most hid the lower half of their faces behind red bandanas. Many were carrying signs fashioned from repurposed “We Buy Houses” placards: “GENTRY GTFO”; “BE WARY OF WHITE MEN.”

“If we don’t fight, we’re guaranteed to lose,” Rompe told them. “But if we do fight, we may not win — but at least we have a chance. So why not fight?”

Among the masked marchers, several key activists were recognizable. There was Rompe, a self-described “Marxist-Leninist-Maoist” who, as a member of the Red Guards — Los Angeles and a founder of Serve the People — Los Angeles, has cited Turkey’s Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front as his inspiration. (Both the United States and the European Union classify the group as a terrorist organization.) There was Angel Luna, a Boyle Heights native and newly minted UCLA grad — double major in English literature and Chicano studies with a minor in geography — whose family was twice evicted during his childhood and who is now a “self-professed Marxist-leaning nerd liv[ing] with five roommates in a two-bedroom house” in the neighborhood, according to a recent World Magazine report. And there was Nancy Meza, another local who helped launch Defend Boyle Heights after leaving her job as a communications and marketing associate at the more conventional East LA Community Corporation in 2016.

The group walked west on East First Street, beneath the 101 freeway and toward the Los Angeles River. Both landmarks embody their neighborhood’s plight. After racial redlining policies forced Latinos east, away from the Westside’s wealthier, all-white communities, the 101 and a tangle of other freeways sliced through Boyle Heights, displacing 10,000 residents and cutting it off from the rest of the city. Likewise, the river divides the neighborhood from the Arts District — a formerly lifeless part of downtown Los Angeles that has recently been upended by gentrification. Between 2000 and 2014, rents there rose 140 percent. (In the county as a whole, the rate was much slower — a mere 25 percent.) Today, the Arts District is crowded with designer boutiques and chef-driven restaurants, and the galleries for which it was named have since forded the river in search of cheaper rents. The Sixth Street Viaduct, a $480 million, Michael Maltzan-designed bridge between the two communities, is slated to open in 2020 — and it is only expected to hasten the spillover.

“Se ama y se defiende!” the activists chanted. “El barrio no se vende!”

“What do we have?” the ringleaders shouted.

“Nothing!” their followers responded.

“What do we want?”

“Everything!”

Four police cars with flashing lights drove behind and ahead of the activists; others were parked along side streets.

“Pigs go home!” yelled the activists.

Defend Boyle Heights’ first target — the first stop on its tour — was a seemingly unlikely one: Self Help Graphics & Art, at the corner of First and South Anderson. Founded in 1970 by a Franciscan nun, the not-for-profit arts collective has long promoted the work of Chicano and Latino artists. Last summer, Self Help attempted to broker a truce between the newer galleries and the activists. It did not end well.

“In no time, the meeting went south,” the Los Angeles Times reported, “as about a dozen mostly young activists, some wearing the brown berets of their 1960s Chicano Movement forebears, barged in. One woman covered her face with a red bandana. They accused Self Help Graphics of helping to roll the Trojan horse of gentrification into Boyle Heights by supporting art galleries popping up in the neighborhood.”

To outsiders — and to many Boyle Heights residents — Self Help seems like part of the solution: a nearly 50-year-old refuge for local artists that says it wants to lift up the surrounding community. But Defend Boyle Heights sees Self Help — with its outreach to the new galleries and board members who support redevelopment and urban renewal — as part of the problem: a vendido, or sellout.

“Self Help has a board of gentrifiers!” shouted one of the march’s masked ringleaders. “We don’t want them here because we hate art. We don’t want them here because they’re f***ing displacers. F*** Self Help!”

“Self Help, get the f*** out!” the activists chanted as they rattled the organization’s locked gates and pounded on its dumpsters. “Vendidos, get the f*** out!”

The police sounded their sirens — a sign to move along.

The next stop was 356 Mission, the first of the outside galleries to set up shop in the nonresidential, light industrial zone west of Anderson. (Later arrivals have included Hollywood’s United Talent Agency, which recently opened a space where famous artists could “do business,” and the Maccarone gallery, whose proprietor bragged about the area’s edgy, “dangerous quality” in 2015, adding, “I like that we spent a fortune on security.”)

Academics are divided over whether artists really contribute to displacement; one study by the London School of Economics found that galleries tend to chase gentrification, not cause it. Last fall, Laura Owens, the mild-mannered art world star who founded 356 Mission in 2012, wrote, “The area and community surrounding 356 Mission is one about which I care deeply,” and the gallery’s homepage points out that 100 percent of its profits go to events programming: youth workshops, performances by local artists and political organizing meetings.

“L.A. has an urgent housing crisis that is facing many communities, and Boyle Heights is particularly vulnerable to rising rents and inequity,” Owens wrote. “The relationship between art and gentrification is an urgent issue for the art community to discuss and should be further explored thoughtfully and respectfully between artists, civic leaders, and most importantly the residents of the neighborhood. … [But] the issue is extremely complex and multi-layered, and doesn’t solely rest on the existence or absence of galleries.”

None of this matters to Defend Boyle Heights or its sister group, the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAD). (Popularized by a 2014 article in the Atlantic, the term “artwashing” refers to any form of gentrification in which the artistic community is tacitly complicit.) According to Angel Luna, one of the group’s leaders, “Attacking the galleries is a useful strategy because we are directly attacking the amenities that developers are trying to use to attract new people into Boyle Heights”; others point out that Owens’s dealer and business partner, Gavin Brown, is a multimillionaire who lives in a six-story brownstone in Harlem, another gentrification hotspot.

As a result, gallery-goers have been pelted with water bottles, shot with a potato gun, surrounded, chased, harassed and harangued at any number of events over the last two years — including the opening last October of Laura Owens’s mid-career retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, which Defend Boyle Heights activists traveled thousands of miles to crash.

The group’s demand is as simple as it is uncompromising: Hand over your keys and leave.

“People ask, ‘Why are y’all going after the galleries?’ said activist Nancy Meza as she stood on 356 Mission’s stoop. “Why aren’t you going after the big investors? The night that we disrupted at that fancy-ass museum — only art investors were invited. The who’s-who in the real estate market of art. That’s an example — the real estate agents and the art investors are all the same person.”

When Meza finished, the masked man who had been leading the marchers chimed in.

“356 Mission, they’re really f***ing smart,” he said. “In the past, they used to do black-queer events. People-of-color events. Empowering workshops on trans people. So f*** that identity s***. I don’t give a f*** if someone is black or brown or queer or disabled. If they’re a gentrifier, they deserve to f***ing die.”

Other activists whooped and clapped.

“And that’s the reason we’re doing this tonight,” the man continued. “Because look at us. We’re f***ing scary-looking. If gentrifiers see this, they’re going to be like, “Oh s***.”

***

Looking scary is one thing. Actually halting gentrification — not only in Boyle Heights, but in countless other at-risk neighborhoods nationwide — is something else altogether.

Can Defend Boyle Heights really make a difference?

The group is clearly grappling with that question. Before they made their way to Manhattan’s now-ritzy Meatpacking District to picket Owens’s opening, Nancy Meza and her companions stopped in Chicago and the outer boroughs of New York to listen to like-minded activists, to tour similar battlegrounds and to talk about the lessons they’ve learned in L.A.

They called it their #HoodSolidarity tour.

“We are devoting our time to building a national movement against gentrification,” they wrote in a February blog post titled “Defending Boyle Heights and f***ing s*** up: A 2017 summation and report back from our Hood Solidarity tour.” “Boyle Heights has … become a beacon of hope for other communities facing similar threats. … We are hopeful that in the coming years, with the effort necessary to sustain a movement, poor and working-class people can escalate the class war against gentrification and actually hinder and possibly reverse its effects.”

For now, “movement” is probably too grandiose a word for the anti-gentrification skirmishes spreading eastward from Boyle Heights. But they are spreading.

Last March, protesters scuffled and spouted racial epithets on the sidewalks in front of Uncle Ike’s Pot Shop in Seattle’s Central District, a historically black neighborhood that has become increasingly white (and unaffordable) in recent years. The highly profitable operation is owned by a white real estate developer and sits on a corner once ravaged by the war on drugs, making it a “perfect symbol of gentrification” — and a frequent target of activists.

In May, dozens of alleged anarchists vandalized high-end cars, tagged new upscale buildings and left behind a “Gentrification Is Death, Revolt Is Life” banner in Philadelphia’s Olde Kensington neighborhood, where housing prices have shot up roughly 50 percent since 2014. (Philadelphia ranks first among the 10 largest cities in the U.S. for the number of families living in poverty, with 25.7 percent.)

And in November, and again this January, an anonymous band of “spirits in the night” smashed the windows of Sock Fancy, a self-described “awesomely random sock shop” in the Cabbagetown section of Atlanta.

“While more and more shops, boutiques, coffee shops and condos are built in this former working-class neighborhood, rent prices sky rocket and those who are less fortunate are forced to move elsewhere,” they wrote in an online statement. “With this small action we hope to send a firm statement to all gentrifying businesses that have their sights set on Atlanta: You will not be welcomed here. You will be run the f*** out. Trust us, you ain’t seen nothin yet.”

Perhaps the best places to look for signs of growing national momentum, however, are Chicago and Austin, Texas. There, sympathetic activists have formed satellite groups of sorts — autonomous cells inspired by what’s happening in L.A., if not directly connected to it.

In Austin — now home to three of the five most expensive zip codes in Texas — a collective called Defend Our Hoodz has focused its fire on the Blue Cat Café, a vegan eatery with more than 200 felines available for adoption. For eight years, the site at the corner of Navasota and Cesar Chavez streets was home to Jumpolin, a beloved, family-owned pi?ata shop. But in February 2015, the store was suddenly demolished on the orders of the landowners, sparking community outrage. Since late 2015, when the Blue Cat took Jumpolin’s place, Defend Our Hoodz and other activists have staged dozens of protests; at one point sprayed “You Gentrified Scum” on the side of the building and glued its doors shut. A recent clash, with white nationalist counterprotesters, ended with stun guns, slurs, arrests, blows and at least one man bloodied on the ground.

“[We want to] tell Austin and anyone coming into our communities that we do not accept the continued erasure of our working class black and brown neighborhoods of the east side,” Defend Our Hoodz wrote on Facebook.

Meanwhile, in Chicago’s Pilsen area, a longtime Latino enclave now facing the same pressures as Boyle Heights, an “art-focused” effort called ChiResists has been “transitioning to help people in the neighborhood” after launching in 2016 to fight the installation of the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock. Last October they co-hosted a free event, Boyle Heights to Pilsen: A Teach In on Resisting Gentrification, at the National Museum of Mexican Art; members of Defend Boyle Heights dropped by on their way to New York. Afterward, both groups wandered the streets of Pilsen and wound up outside S.K.Y. — a new “contemporary American” restaurant with glowing Edison bulbs, $9 black truffle croquettes and $24 foie gras bibimbap — where they confronted general manager Charles Ford.

“You’ve inserted yourself into a community that doesn’t want you, without talking to us first,” one activist said. “It’s national news that Pilsen is fighting gentrification, and you still” went there.

“Is there anything we can do to help?” Ford asked.

“Get the f*** out!” someone shouted.

After three minutes of obscenities, Ford reached for his phone and dialed 911. The next day, S.K.Y. and a nearby restaurant named Dusek’s had been defaced by anonymous taggers: “YT PPL OUTTA PILSEN.” On Facebook, ChiResists posted two photos: one of the graffiti on Dusek’s, and another of a family being evicted in Logan Square.

“When ppl care more about graffiti than they care about the economic instability and displacement created by gentrification,” the caption read.

In Pilsen or East Austin or Boyle Heights, it’s easy to find locals, young or old, who are concerned about gentrification but confused by, or just plain opposed to, these new, more aggressive tactics. And if you ask experts who have been studying the phenomenon — or the more conventional activists who have been battling it for decades — they always respond the same way. Gentrification is a huge, even global, force, they say. Resisting it in the streets isn’t sufficient. You need a seat at the table — and a plan.

“The younger generation is fed up,” explains Byron Sigcho of the Pilsen Alliance, a social-justice nonprofit that has been fighting gentrification since 1998. “The frustrations they face are real; the issues are systemic and oppressive. They’re not able to go to school, they’re not able to find a good job. I understand their anger. But real issues need real solutions. We need to push for rent control, for affordable housing, for community benefit agreements, for policy change at the urban development level. We can’t just inflate the same divides we criticize.”

Sigcho and company aren’t wrong. But so what? say groups like Defend Boyle Heights. Activists have been floating these ideas since before we were born — and gentrification is only getting worse. Now’s the time to “make s*** crack.” We can put it back together later.

It isn’t impossible to imagine a model for fighting gentrification that unites the hardliners, the more mainstream activists and the broader community. The mariachis of Boyle Heights are a good example. When their new landlord, Frank “B.J.” Turner, raised rents on a handful of long-term tenants by 60 percent and 80 percent and rebranded the building “Mariachi Crossing” — trading on their cultural cachet to attract wealthier tenants looking for a “vibrant” neighborhood and a quick Metro ride downtown — the mariachis and other residents launched a rent strike. It lasted nine months. Turner finally backed down and agreed to meet with the tenants after members of various groups — the Los Angeles Tenants Union, Union de Vecinos, the Democratic Socialists of America — Los Angeles, Ground Game LA — spent last fall occupying the sidewalk in front of his house in Rancho Park.

A deal was announced in February: a 14 percent rent increase; new, good-faith negotiations in 2021;, and all necessary repairs. The mariachis had won. And while Defend Boyle Heights, BHAAD and other militant groups supported the strike, the tenants themselves thanked many other allies as well, including “lawyers from the Los Angeles Center for Community Law and Action for steering [them] through a complex legal system, Councilmember José Huizar, lawyer Richard Daggenhurst, and their own neighbors for having been willing to put the larger community’s needs ahead of their own.”

Whatever comes next, conflicts over housing, commerce and culture won’t subside anytime soon, especially in cities where the vast majority of young people come from disadvantaged minority groups. Nationwide, the majority of babies born since 2015 are racial or ethnic minorities, and today’s young people are also substantially more minority than older, more prosperous generations. That creates new fault lines in today’s intergenerational fights over gentrification — fault lines that run deep in cities. Los Angeles is only 29 percent non-Hispanic white to start with; among younger Angelenos, that fraction is even smaller.

Also complicating the picture: American young people are increasingly living with their parents, which is to say not moving away from communities of origin and starting their own households. More than half of younger millennials have yet to leave the nest, and black and Hispanic young people are more likely to stay put than whites. Not only are they less upwardly mobile — they are less mobile, period.

Ultimately that means they’re still around to notice and object to newcomers who move into their neighborhoods, and primed to resent privileged peers who can start independent lives thanks to their access to worlds that seem impossibly distant and opportunities that seem out of reach.

Meanwhile, the gentrifiers will keep coming. According to a 2016 analysis by University of Illinois at Chicago professor John J. Betancur and doctoral candidate Youngjun Kim, about 10,000 Latino residents have left Pilsen since 2000 — and for the most part, they haven’t been replaced by other Latinos. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Berkeley, recently found that between 2000 and 2010, more college-educated individuals moved to urban centers than to the suburbs in a majority of America’s 50 largest metro areas; they concluded that “urban revival in the 50 largest cities is accounted for almost entirely” by this trend. Examine individual-level census data more closely, and you can come up with an even clearer picture of who’s reoccupying our cities. According to economist Jed Kolko, the influx is heavily skewed toward one group in particular: “rich, young, educated whites without school-age kids.”

***

Around 9 p.m., Defend Boyle Heights arrived at its destination: Dry River Brewing, a small craft brewery and taproom on Anderson Street that specializes in esoteric sour beers, including a “persimmon-hued Calilina” that deftly “balances a robust yeast-driven aroma with a complex cereal character and just enough berry and lemongrass flavors,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

En route, the activists debated whether they should continue.

“Next time we won’t put this s*** on Facebook,” one said as he flipped off the police cars that were still following the march; another started to tag the outer wall of a warehouse but only got as far as “F*** HIPST” before he dashed away, afraid that a cop had spotted him.

“Should we keep going?” someone asked. “They’re going to be at every f***ing stop.”

The group huddled to reassess.

“We know the cops are going to be there — so we can’t fully ‘express ourselves,’” the ringleader said. “But we want to go to the f***ing brewery, ’cause the breweries are the newest gentrifiers. Our homies are going and having a beer with the f***ing gentrifiers who are displacing their parents. That s*** makes us really angry — and I think it would be proper if we could at least tell them how angry we are.”

“I say we go!” someone yelled.

“Yeah!”

As soon as Defend Boyle Heights arrived at Dry River, the chanting began.

“Hey, hey, ho, ho! These gentrifiers have got to go!”

Suddenly a metal construction sign smashed into the fa?ade of the taproom; shards of concrete flew through the front door. Inside, patrons who had been enjoying their snifters of Lady Roja beneath windows “adorned with local succulents” scrambled as chaos overtook “the rich sounds of eccentric grooves” that had been playing on the brewery’s “vintage stereo system.” (The descriptions come from Dry River’s website.) For a moment, Dry River’s “iconic, apocalyptic, barn door” slid shut, but then brewmaster Naga Reshi emerged to calm the crowd.

“Get the f*** out of Boyle Heights, you hipster!” shouted a man in a red L.A. Tenants Union sweatshirt. “Pack your s*** and get the f*** out!”

Reshi smiled serenely and pressed his palms together in a “namaste” pose.

“Get the f*** out!” the activists screamed.

A Dry River patron in a black T-shirt, a beard and a ponytail tried.

“I grew up here!” he yelled. “I grew up in Boyle Heights! This is my neighborhood too! You guys want change through violence?”

“Gentrification is violence!” a young woman replied.

“F*** you, vendido!” added a burly activist in a black hoodie. “F*** you, coconut!”

Eventually the police stepped in.

“Control your group,” one officer said. “This is your warning.”

“This is your warning!” the young woman spat back.

But for now, at least, there was nothing else to do. The evening’s mission had been accomplished. As the activists retreated, the owners and patrons of Dry River picked up their reclaimed-wood benches and replaced them on both sides of the taproom entrance. They shook their heads. The eccentric music resumed, but the groove was gone.

Farther down Anderson Street, Defend Boyle Heights could still be heard chanting.

“We’ll be back,” they called into the night. “And we’ll be bigger.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: