Nitrate has plagued Wisconsin's groundwater for decades. Why is the problem so hard to solve?

CASCO, Wis. - When Tyler Frye purchased his home in 2020, he saw the Casco area in Kewaunee County as the perfect place for him and his fiancée to start a family. The house was new, in a just-built subdivision close to his family and the area where he grew up. He snapped it up.

Then he discovered nitrate contamination in the water.

"When I bought the house, I falsely assumed with the new well, the water would be safe," he said.

Since then, he and his fiancée, Shannon, have married, but the question over what to do about the water remains. Frye gets angry if he thinks about it too long, he said. And the couple is worried that if they have children in the house, it could put them at risk for health issues. Drinking water with elevated nitrate levels poses special risks to infants and is being increasingly linked to cancers and other diseases in adults.

"It was pretty devastating," he said. "Owning a home is the American dream. I went to college, got a degree, got a job. I sacrificed a lot to make money to buy a nicer house."

The contamination makes the worth less than Frye paid for it, so selling would be a financial hit. But keeping it means maintaining a filtration system indefinitely to lower the levels of nitrate in the water, but it still wouldn't reduce nitrate to nondetectable levels.

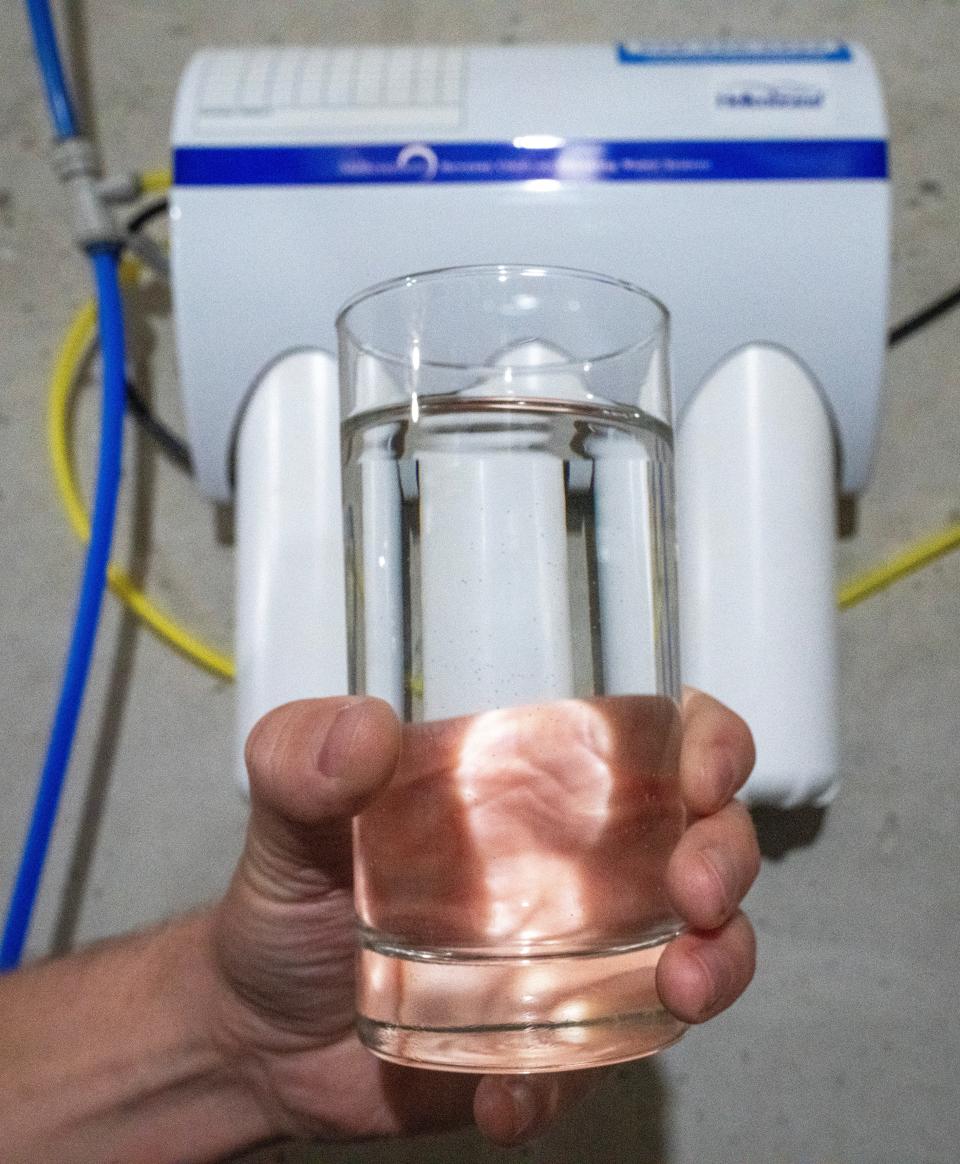

Frye bought a $1,000 reverse osmosis system, which brought the nitrate levels down from 17.4 parts per million to 3 ppm, but he's leery of having any detectable amounts of nitrate in his water.

"It's unsettling," Frye said. "And we talked about once we start having kids, we're not going to trust it to provide water for our kids."

Nitrate is the state’s most widespread contaminant of groundwater. About 10%, or 80,000, of the state’s private wells fail to meet the state drinking water standard of 10 mg/L. In heavily farmed areas, that percentage can rise upwards of 20%, according to a 2023 report to the Legislature from the state's Groundwater Coordinating Council.

The contaminant mostly comes from manure or fertilizer but can also originate from septic systems and other sources.

In the 2023 report, members of the Groundwater Coordinating Council noted that nitrate contamination has been impacting Wisconsin waters for more than 50 years. That decades-long struggle, with not much to show for its efforts, has left people fatigued and apathetic, especially as new water quality concerns like PFAS continue to emerge. PFAS, also known as "forever chemicals," are man-man compounds that are used in products like firefighting foam and water-proof clothing that are known to last for decades in the environment.

While tighter rules have been proposed, Wisconsin has largely lost steam in its regulation of nitrate, leaving more headaches for private well owners across the state. To some, the issue feels insurmountable. Some don't even want to test their water, for fear of unearthing the problem.

"Nitrate is really hard for people," Jen McNelly, formerly Portage County's water resource specialist, said in a December 2023 interview. McNelly has since departed for a position at UW-Madison’s Division of Extension. "People get exhausted talking about it, to a certain extent, because there is no easy answer and there’s no silver bullet."

Complicating matters is the role that agriculture — a critical part of Wisconsin's economy, history and culture — plays in nitrate contamination. Some farmers are reluctant to change practices unless homeowners are also willing to examine their septic systems. Others acknowledge the negative impact of nitrogen fertilizers but are hamstrung by market forces that consistently demand bigger crop yields.

Wisconsin is far from the only state struggling to remedy nitrate contamination. In Minnesota, the EPA has told the state to take more action to protect its residents. In Nebraska, owners of private wells are being urged to test their private wells to gather more data on the extent of nitrate contamination. In Oregon, private companies are offering to chip in to help with nitrate pollution, after more than 30 years of struggles.

As time goes on, though, more Wisconsinites like Frye are unable to freely drink the water that comes out of their tap. And they may not have another 50 years to wait for a solution.

Nitrate's health risks pose worries

Nitrate forms when oxygen combines with nitrogen-rich sources like fertilizer, manure or waste from septic tanks. It slips easily into groundwater by way of rain or melting snow, especially in places with shallow soil or fragmented bedrock.

1994 research from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point found that 90% of nitrogen inputs to groundwater can be traced to agriculture, with the rest coming from septic systems and lawn fertilizer. Kevin Masarik, a groundwater education specialist at UW-Stevens Point, said the breakdown of sources likely has not changed since then.

Farming remains a crucial part of Wisconsin’s economy, and applying nitrogen fertilizer can increase crop yields. The problem arises when more nitrogen is applied to the ground than the plants can take up, which means it'll get into the groundwater somehow, said Steve Elmore, program director of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources' Bureau of Drinking Water and Groundwater.

Since farmers want to maximize yield, they may add extra fertilizer as "insurance," Elmore said. But that's not the only reason. If heavy rain falls after a farmer has recently laid down fertilizer, it can be washed away.

Even if fertilizer is applied with great care toward the timing and amount, it could still leach too much nitrogen into groundwater. That's because it just takes a lot of nutrients to grow row crops, Elmore said.

Large farms, or concentrated animal feeding operations, are also a source of nitrate contamination, because of the large amounts of manure produced by the animals. The manure is typically mixed with water and stored in tanks or lagoons, then spread on farm fields, where the nitrate can sometimes run off into streams, rivers and lakes, or soak down through the soil and into groundwater.

Nitrogen can be damaging to the environment when it's washed into surface water, driving excessive algae growth and causing harm to fish and other aquatic life. But there are dangerous consequences if too much ends up in groundwater — the source of nearly 75% of Wisconsin's drinking water.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sets the maximum contaminant level for nitrate, or the amount that's considered safe for drinking water, at 10 mg/L. That level was set to protect infants from blue baby syndrome, which occurs when there's not enough oxygen in a baby's blood and can be caused by high nitrate levels in drinking water.

There's been less study of what elevated nitrate can do to adults, but some research is beginning to show broader health impacts. A 2018 review of studies of the health impacts of nitrate found that risk of illnesses like colorectal cancer, thyroid disease and neural tube defects increased even when people were ingesting nitrate in their drinking water below the maximum contaminant level.

Even though the health risks may not yet be fully understood, people are beginning to worry. Kriss Marion, a Lafayette County supervisor and clean water advocate, said she attends a lot of funerals, not unusual for an aging community. What is unusual is the number of young people in the area getting cancer and dying, too. Lafayette County is in south-central Wisconsin, one of the state's hotspots for nitrate contamination.

"A lot of conversation at funerals is about water — whether water was the reason," Marion said.

Wisconsin's nitrate problem is growing

Nitrate trends are hard to tease out. One-third of private well owners in Wisconsin have never had their well tested for nitrate, and even private wells that have been tested aren't usually sampled consistently over time. Further, extreme weather swings wrought by climate change, like floods and droughts, cause nitrate levels in groundwater to fluctuate.

But the data that are available show — and state water quality experts agree — Wisconsin is losing ground on its nitrate problem.

One way to assess nitrate trends is by looking at the levels in surface water. A large chunk of the state is covered by "groundwater-dominated" watersheds — in other words, streams and rivers that flow through the area are resupplied by groundwater. Nitrate is increasing at most of the sites where the DNR monitors surface water quality.

Elmore acknowledged that Wisconsin continues to struggle with nitrate contamination, especially in comparison to its handling of another common component of fertilizer, phosphorus. In 2010, Wisconsin enacted some of the most stringent regulations in the country to address phosphorus. DNR surface water quality monitoring shows concentrations of phosphorus are decreasing in most rivers across Wisconsin.

The DNR first launched the rulemaking process for standards regarding nitrates in groundwater in December 2019 in a bid to keep the nutrients from affecting soils and geology most vulnerable to contamination. The rulemaking process typically takes 30 months and then requires signoff from the Legislature. But the rule had to be abandoned in 2021, due to the high estimated cost to businesses.

Outside of setting rules, encouraging farmers to take up practices that protect soil health can decrease nitrogen leaching. Elmore said cover cropping, which covers and enriches the soil outside the growing season, and no-till farming, which minimizes soil disturbance, can be useful.

But making a wholesale transition to those practices can be costly to farmers. If people want to keep their drinking water safe, they could expect to pay more at the grocery store for food that was cultivated that way, Masarik suggested — similar to higher-priced grass-fed beef or organic products.

'We're not attacking farming'

Kewaunee County, where Frye lives, has become a flashpoint in Wisconsin's debate over nitrate contamination.

The karst geography, which consists of rock that easily allows contamination from the soil to sink into the groundwater, makes the area more susceptible than most other areas of the state. And with a growing concentration of mega-farms that spread large amounts of liquified manure each year, the problem isn't getting any better, despite residents' outcries.

Many of the homeowners in the county have seen contamination in their wells, requiring filtration or routine sanitation. Rhonda Spude, a resident of Algoma who grew up in the area, has had consistent levels of nitrate and bacteria in her well for years. While the nitrate level is hovering just under the state's limits, the reoccurring bacteria makes her water unsafe to drink without boiling.

For the most part, her family now just uses bottled water, which they pay for out of their own pockets.

It's frustrating because growing up in the area, there weren't any factory farms, and her family never had issues with water quality. And from Spude's perspective, it seems like the county and the state aren't doing anything to make the situation better for her and her neighbors.

"They go round and round, and it's like nobody wants to take the blame for anything," she said. "They tried to say it's not anything that's that bad. Well have you had that problem? We've been dealing with it for years."

Nancy Utesch, a resident of the city of Kewaunee, and her husband have been working on the issue for years, pushing for solutions and regulations to protect the groundwater that so many residents rely on for drinking, cooking and bathing.

The work she does to inform the community of the risks tied to water contamination constantly receives criticism, because the farms in her area produce large amounts of food.

"At a local meeting, somebody said 'You shouldn't complain with a mouthful of food.' And that's where the conversation tends to go," she said. "But we're not attacking farming. My husband and I are farmers. We own 150 acres here, we own beef cattle and have a rotational grazing system and we understand farming. But we have to find a way where farming does not mean destroying our water."

One of the largest factory farms in Kewaunee, Kinnard Farms, has faced issues related to the amount of manure spread across the county. The farm was ordered to cap the number of cows it kept, and to install monitoring wells on fields that it spread on to monitor the groundwater, following a settlement with the state. The farm last year agreed to begin treating liquid manure instead of applying it to fields, in order to avoid having to install the monitoring wells, which the farm said could become costly.

But even with the settlements, there has been contention over the high concentration of factory farms in Kewaunee, and the growing number of private wells impacted by nitrate.

When residents pointed out consistent harm, blame was shifted elsewhere – to septic systems that had to be replaced.

But the contamination still lingers.

Utesch said the thought that pollution needs to be excused because farms are providing food isn’t correct.

"It's not a good enough thing to say, 'We're feeding you so your water is now going to be poisoned,'" she said.

"What we need is a farm model that seeks the idea of growing nutrient dense food that is actually healthy for people, for the environment and cares about the water. As long as we are hell-bent on growing corn and soy, we're going to have nitrate problems."

'There is no easy answer'

In Portage County, McNelly described nitrate as "by far our single biggest drinking water issue." She estimated 22% of the county's private wells exceed the drinking water standard for nitrate.

Located in Wisconsin's Central Sands region, named for its sandy soils, Portage County is a top potato producer. Nitrogen is critical to growing potatoes and getting high yields. The advent of irrigated agriculture also made a "huge change" to the productivity of the county's farmland, McNelly said — but irrigating fields with water that's high in nitrate and adding fertilizer on top worsens contamination.

County officials began to worry about nitrate in the 1970s and 1980s, McNelly said, leading to one of the state's first groundwater management plans. But they're still struggling with it today.

While some farmers are working on reducing the amount of nitrogen that goes onto their fields, the hard evidence on nitrogen reduction practices is still being developed, she said.

In the meantime, she said she wanted people whose drinking water is polluted to be able to use it again. McNelly and others have criticized the limitations of Wisconsin's well compensation program, which offers funding to replace a contaminated well but requires that a person have livestock and a nitrate level of 40 mg/L — four times the safe drinking water standard — to be able to access the funds.

The state used ARPA funding to launch a similar program open to anyone, which McNelly said has been used "heavily" in Portage County, but when she spoke with the Journal Sentinel in December, she'd recently received an email saying the money was running out. Elmore, with the DNR, called the $10 million in ARPA funding "a very small dent" in the estimated $450 million that would be needed to replace all the state's contaminated wells.

Katy Bailey, who bought what she and her husband thought would be their forever home in Nelsonville in 2012, used those well compensation funds to install a new well before the couple sold their house last July and moved to Wisconsin Rapids. Bailey and other Nelsonville residents were profiled in a Wausau Daily Herald story in 2020 about their fears that manure from a CAFO about a mile from the small Portage County community was leaching nitrogen into their groundwater.

Bailey, her husband and her young son all have thyroid issues, one symptom health officials say may be caused by continually consuming high levels of nitrate. It was the birth of her son that Bailey said caused her to think seriously about moving away from the village that she had grown to love.

"I really do think it was the discovery of the high nitrates that really fractured the whole integrity of the community," she said.

'What do we do now?'

In south-central Wisconsin, home to some of the most heavily farmed land in the state, a study meant to assess groundwater contamination momentarily exploded into the spotlight, but has since faded into the background.

The Southwest Wisconsin Groundwater and Geology Study, or SWIGG, as it came to be known, evaluated 840 samples from residents’ private drinking wells in Grant, Iowa and Lafayette counties for nitrate, total coliform bacteria and E. coli. Some mid-study results drew fierce backlash in 2019 when news reports misconstrued a statistic showing 91% of a sample of contaminated wells contained fecal matter.

But the study’s final results, published in 2022, have languished even though they show that the nitrate contamination in wells is severe.

In Lafayette County, for example, 27% of wells tested in November 2018 and 20% tested in April 2019 had unsafe nitrate concentrations.

The researchers found that the more acres of agricultural land near a well, the more likely the well water was to have elevated nitrate levels. No such association was found with proximity to septic systems, said Joel Stokdyk, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who co-authored the study.

But fecal contamination in the samples came from both humans and animals, casting blame on septic systems.

“When (the results) did come out, they were sort of confusing enough that it made it hard for people to rally around any particular take or response,” said Marion, the Lafayette County supervisor.

That's clear in the variety of actions county officials have since tried to pursue to improve the area's groundwater. Erica Sauer, Lafayette County’s conservation, planning and zoning manager, has pushed to require manure storage facilities in the county to be constructed to minimize leakage and helped residents seal up abandoned wells so pollution can’t continue to seep into the ground. The county’s health department also set up a water testing lab for people to regularly test their well water.

Erik Heagle – Grant County’s conservation, sanitation and zoning administrator – wrote in an email that his department has focused on enforcement of septic system compliance and revamping its Farmland Preservation Program to have stricter standards on nutrient and manure spreading.

But he reported waning attention to the issue from the public.

“There is a willingness to address the issue,” Heagle wrote, “it just doesn’t seem like there is a sense of urgency about it.”

While Marion said people with polluted wells were showing up in droves to demand answers at county board meetings when the first round of study results dropped in 2019, both the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of other pressing environmental issues, like PFAS, have deflated most of that pressure.

Most of all, she hopes to see more people encouraged to regularly test their well, even though they may hope their water is perfectly fine.

"We know a lot more than we did before," she said, "but science is only as powerful as your willingness to use it."

Scott Laeser, a Lafayette County resident, organic vegetable farmer and senior working lands advisor for the Rural Climate Partnership, said he felt the nitrate findings were eclipsed by the findings about fecal contamination.

Pointing fingers about who’s more to blame for pollution distracts from the science that clearly shows a problem with nitrate contamination, one that he feels has a clear major source: agriculture. Eventually, he said, the state will have to interrogate what it grows and how it farms.

Some of that work is taking place right in Lafayette County. In 2023, Wisconsin's Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection dispersed its first grants for the Nitrogen Optimization Pilot Program to farmers across the state interested in collecting more data about their nitrogen fertilizer use.

Mike Berget, whose family grows over 10,000 acres of corn and beans and produces weaner pigs near Wiota, is one of those farmers. He's part of his local farmer-led watershed group — the Lafayette Ag Stewardship Alliance, or LASA — and he and three other farmers in the group will be testing different nitrogen rates on a rye cover crop to determine the amount that can produce a good corn yield but not leach into the soil.

LASA paid for Lafayette County's portion of the SWIGG study because farmers wanted to know what was going on, Berget said. He believes many of the tainted wells were contaminated decades ago, when farming practices were different, and thinks high fertilizer prices are causing farmers to apply less of it today.

Cutting down on nitrogen now to save money may lead farmers to stick with that reduced application, Berget said, if they see that they were able to get just as good a yield.

"Sure, we're not going to correct things overnight," he said, "but we've got to start somewhere."

Laeser would like to see more urgency from people tasked with correcting things.

"We're spinning our wheels on pollution when we recognize it's going to take time to fix this issue," Laeser said. "The people that are really getting the shaft are the ones who have contaminated water right now, and aren't getting the help they deserve."

Laura Schulte can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter at @SchulteLaura. Madeline Heim is a Report for America corps reporter who writes about environmental issues in the Mississippi River watershed and across Wisconsin. Contact her at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin nitrate contamination has put water at risk for decades

Solve the daily Crossword