The Nixon rulings at the centre of Trump’s Supreme Court immunity case

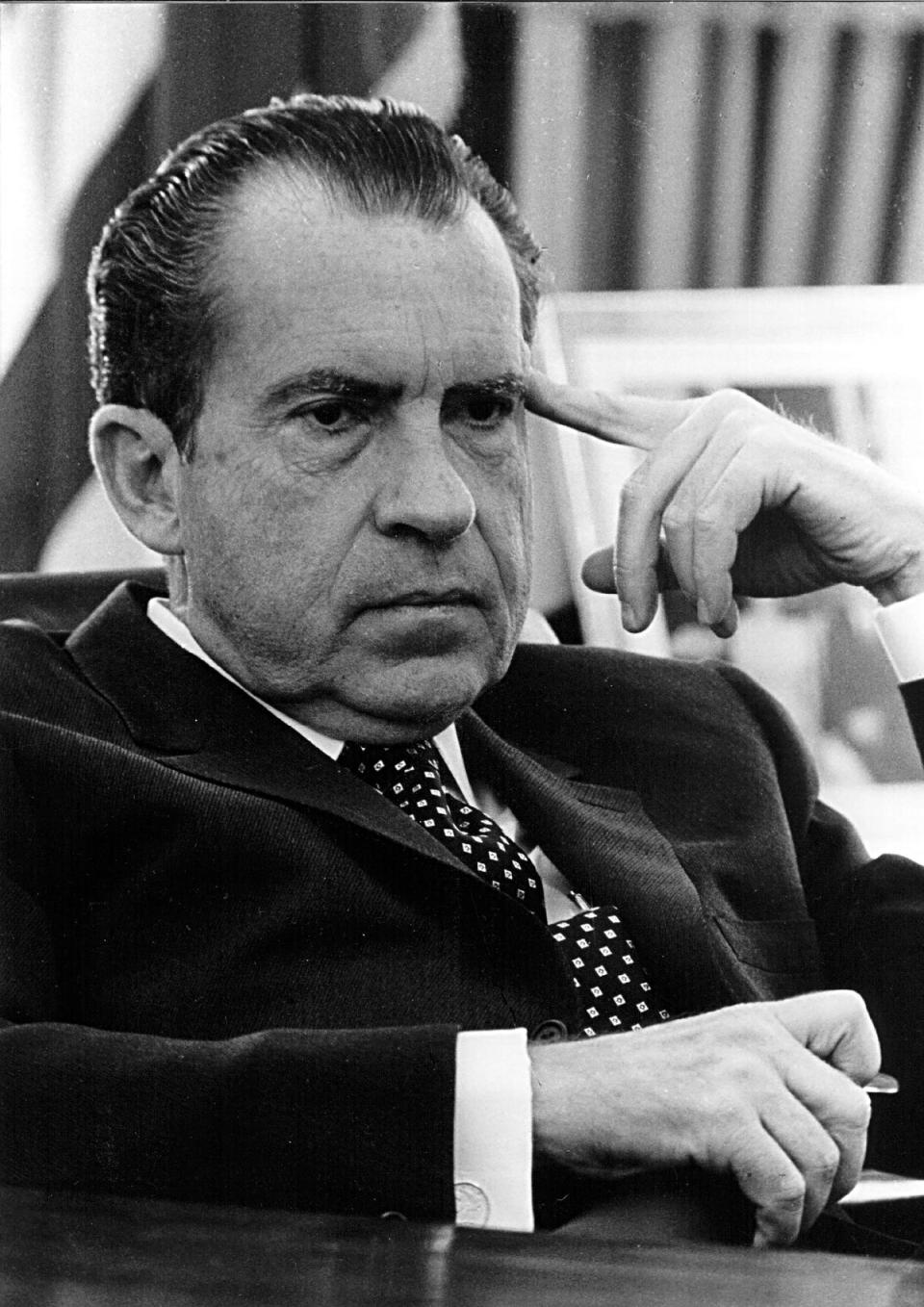

Whether or not Donald Trump has immunity from criminal prosecution will be debated by the Supreme Court justices on Thursday, and both the former president and special counsel Jack Smith have cited court cases involving former president Richard Nixon to make their points.

But the two sides are using the Nixon cases to push opposing arguments.

Mr Trump is pointing to the 1982 Supreme Court case Nixon v Fitzgerald to argue that he should be immune from prosecution on federal election interference charges.

Meanwhile, Mr Smith is using the 1974 Supreme Court case United States v Nixon to argue that he should not be.

The facts and rulings in each case involvingthe late scandal-plagued president offer a glimpse into the case involving today’s scandal-plagued former president now before the nation’s highest court.

Here is what you need to know about the cases – and how they are at the centre of Mr Trump’s presidential immunity case:

Nixon v Fitzgerald

Mr Trump’s team heavily relies on the Nixon v Fitzgerald case, where the Supreme Court ruled that presidents cannot be sued for actions they conducted while in office.

The case began in 1978 when Arthur Fitzgerald – a former contractor for the US Air Force – sued Nixon and other White House aides for damages after he lost his job after giving testimony to Congress.

Nixon appealed to a lower federal court, claiming he had immunity from civil liability. When the judges in the lower court disagreed, the former president took the case to an appeals court. That court also ruled against him.

Then, Nixon appealed the case to the Supreme Court.

Though the case was decided after Nixon left office, the court ruled in his favour, deciding that “the President’s absolute immunity extends to all acts within the ‘outer perimeter’ of his duties of office”.

In his brief to the Supreme Court, Mr Trump’s attorneys have argued he was acting within his official “outer perimeter” when he made false allegations of election fraud and asked then-vice president Mike Pence to overturn the 2020 presidential election results.

“All five classes of conduct charged in the indictment fall within that broad scope,” his lawyers argued.

As well as presidents being entitled to “absolute immunity” from civil lawsuits for actions conducted while in office, his legal team is arguing that this protection should also extend to criminal actions, in order to protect future presidents from “de facto blackmail and extortion while in office… at the hands of political opponents”.

United States v Nixon

The special counsel’s office is citing the second, better-known Nixon case in its arguments to the court.

United States v Nixon is considered a landmark decision and one that ultimately led to Nixon’s resignation in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

As part of an investigation into Watergate, the US government subpoenaed Nixon to turn over tape recordings and papers related to conversations he had with the men indicted for their part in the scandal.

Nixon asked a federal appeals court to intervene and stop the subpoena, which it declined to do.

When he then appealed all the way to the nation’s highest court, the Supreme Court justices issued a ruling that set a historic precedent for the scope of executive privilege.

“Neither the doctrine of separation of powers nor the generalized need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote in the opinion.

Nixon handed over the tapes and papers and resigned 16 days later.

But, beyond Nixon, the ruling meant that a president must comply with a criminal subpoena and that presidential privilege cannot excuse someone from the judicial process.

For Nixon, president Gerald Ford ultimately granted him a pardon – something Mr Smith points to in his brief to the court as an example of the ruling applying to Mr Trump’s situation.

Citing the case heavily, Mr Smith said that “recognition of petitioner’s immunity claim would prevent Congress from applying the criminal laws equally to all persons—including the President. His immunity claim thus contradicts bedrock principles by placing the President ‘above the law’”.