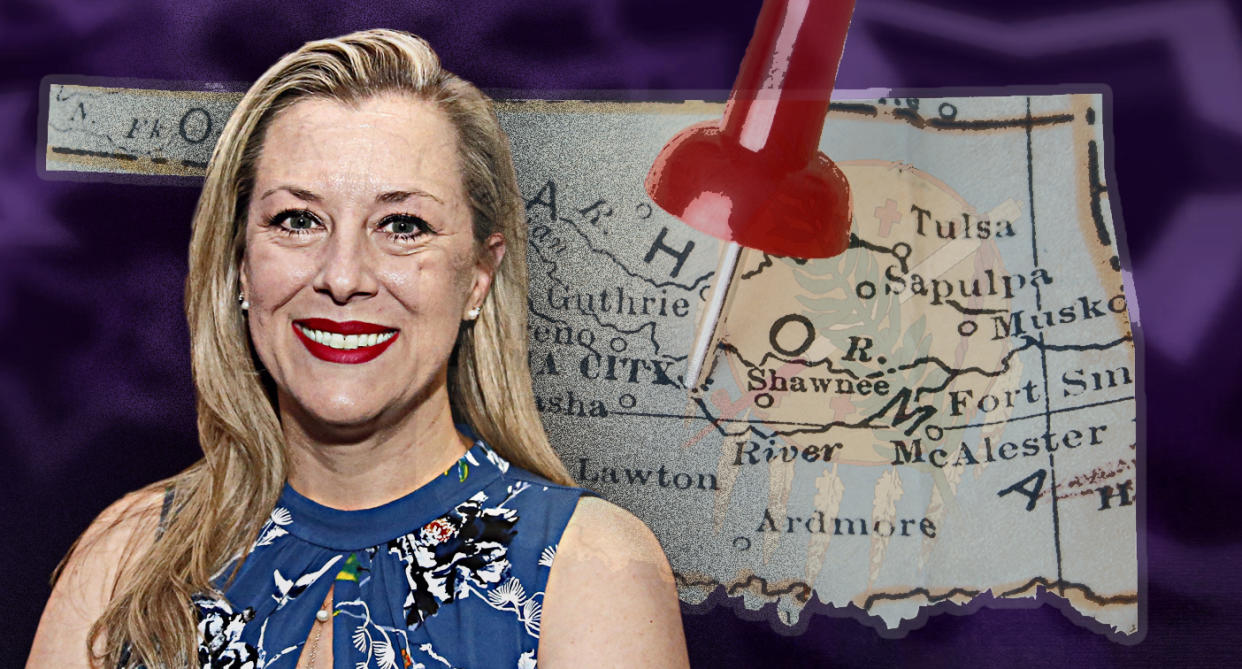

Oklahoma City: If a Democrat can make it there, she can make it anywhere

When Democrat Kendra Horn began talking to people last year about possibly running in Oklahoma’s Fifth Congressional District, the universal reaction, even from some of her friends, was bewilderment.

“Oh, honey,” someone responded sympathetically, the way they might if she announced she was having surgery. “Bless your heart.”

After all, Oklahoma was not just any red state, it was blood red — so conservative that elected Democrats had been driven into near extinction. In 2016, Donald Trump won Oklahoma by more than 36 points — a margin surpassed only by results in West Virginia and Wyoming. Republicans controlled all elected statewide offices, including the governorship and its two U.S. Senate seats. They held a supermajority in the state House and Senate, controlling more than 70 percent of the seats in each chamber.

And since 2012, the GOP had held all five of Oklahoma’s U.S. House seats. In the Fifth Congressional District — which includes part of Oklahoma City, the state capital and two heavily rural neighboring counties to the east of the city — no Democrat had won since 1974, and 2018 did not look especially promising.

Rep. Steve Russell, a decorated combat veteran who commanded an Army unit that played an integral role in capturing Saddam Hussein and who had appeared on the television show “Deadliest Warrior,” had held the seat since 2014. He had easily won two terms — defeating his Democratic opponents by 20 points or more in the last two elections — and was considered a sure thing for re-election in a district where Republicans held a significant voter registration advantage over Democrats.

But Horn, a 42-year-old Oklahoma City attorney who had spent time as a congressional press secretary before returning to her home state to work with groups that help train women to run for office, felt something was shifting in the state. She saw a more politically engaged electorate and a sense of anger at the status quo that she thought might be enough to give even a Democrat a path to victory if the candidate worked hard enough.

Others weren’t convinced.

“People thought I had lost my mind,” Horn said.

Like many Democrats who ran in 2018, she told a similar story of waking up after the 2016 election and feeling called to service. It wasn’t just Trump’s victory that was a motivator, but myriad other issues facing Oklahoma. That included a budget crisis fueled by deep tax cuts that had hit the state’s already starved education system especially hard, leading to a teacher shortage and forcing more than a quarter of Oklahoma school districts to hold classes just four days a week. The crisis led to nine-day statewide teacher strike this year in which tens of thousands of educators, parents and students marched on the capital to demand increased education funding — a degree of political protest nearly unheard of in conservative Oklahoma.

A fifth-generation Oklahoman who grew up in rural Chickasha, southwest of Oklahoma City, Horn had spent the last several years coaching women to become more civically engaged, arguing that female lawmakers could be the ones to bring more civility and compromise to a political system broken by extreme partisanship. It was women, she argued, who could make a difference. Now she looked in the mirror.

“I realized I had to take my own advice,” she said.

What happened was what some have described as the most shocking upset of the midterm elections. In a development that no one saw coming, including political forecasters who predicted up until the final hours before Election Day that the district would remain safely Republican, Horn narrowly defeated Russell — by just 3,300 votes, or 1.4 percent. She made history, and not just for turning the district blue for the first time in 44 years. In a state that ranks lowest in the nation for women in elected office, Horn became just the third woman — and the first Democratic woman — elected to Congress from Oklahoma.

But Horn’s win wasn’t the only surprise on Election Day. Up and down the ballot in Oklahoma, more than a dozen Democratic women claimed seats in what were presumed to be red districts, including four in local and state legislative races in and around Oklahoma City. Among the candidates were teachers like Carri Hicks, who ran for state Senate and won. She was just one of about two dozen educators who ran for political office this year, hoping to shape education policy in the state.

The success of Horn and other Democratic women wasn’t enough to shake the GOP hold on Oklahoma politics. Republican businessman Kevin Stitt won the state’s closely watched gubernatorial race, and the GOP added a few more seats in the state Legislature, protecting its supermajority. But how it played out has some wondering if Oklahoma’s future might be a little less bright red in future elections. Some wonder if it could be part of the shifting electoral map where districts in once reliably red states like Texas and Arizona seem to be more in play, especially for congressional candidates. At the same time though, while urban areas like Oklahoma City flipped from red to blue, rural areas went from red to even more red.

Slideshow: Oklahoma teachers go on strike and rally at State Capitol >>>

But while Republicans won, the new legislators aren’t uniformly hard-right conservatives, the faction that had dominated the statehouse in recent decades. Many of those lawmakers were ousted in the primaries — in part because their more moderate Republican colleagues had campaigned against them. Some had even dared to campaign less on social issues and more as pro-government conservatives willing to raise taxes to fix the state’s fiscal woes, including education funding.

“Philosophically, Oklahomans are conservative in their thinking,” Bill Shapard, a leading pollster who runs the nonpartisan Sooner Poll, wrote in an analysis. “But, situationally, Oklahomans are much more pragmatic. If there is a core-service funding problem and good teachers are leaving the state, Oklahomans say fix it — even if that means new taxes.”

Many credit shifting demographics for the changing political landscape, especially in Oklahoma City. Hit hard by the 1980s oil bust and later by the terror bombing of a federal office building in 1995 that killed 168 people, Oklahoma City responded with an economic redevelopment plan that transformed much of the city with new parks and sports and cultural attractions. The project helped lure an NBA team and tens of thousands of new jobs and shifted the city’s image from a sleepy town that young people sought to escape into a place they wanted to live. And like Dallas and some other Texas cities that underwent similar demographic shifts, Oklahoma City attracted new residents from more liberal states such as California, drawn by affordable home prices, a low cost of living and small business opportunities.

“Suddenly, you have more people here that are more invested and care about the community, and that’s really changed things,” said Sara Jane Rose, a California transplant who founded Sally’s List, a nonpartisan group that works to recruit, train and elect female candidates in Oklahoma.

According to Horn, the changing demographics of Oklahoma City had a dramatic impact on her race, where she found support among younger voters and women who turned out in droves to volunteer for her campaign. When she announced her candidacy in 2017, more than 350 people showed up on a sweltering July day. The event was crowded, hot, sticky — and “fantastic,” Horn recalled. “It was all these new faces, and it was beautiful. … And that’s how we did it. We changed the conversation. We changed the way campaigns were run. We changed the voices that were involved purposely and intentionally. We brought in young people. We encouraged communities that hadn’t been involved before to get involved, and they did.”

The energy wasn’t just around Horn’s campaign. Even in conservative Oklahoma, Trump’s election seemed to spark something. Women who weren’t politically active before were suddenly woke. In Edmond, a tony suburb north of Oklahoma City that is home to a large evangelical population and has tended to vote Republican, a Democratic women’s club founded in response to the 2016 election went from monthly meetings that included just a handful of women to numbers approaching 300 or more in recent months. The group became volunteers in the ground campaigns for Democratic candidates around Oklahoma City, including Horn, knocking on doors and running phone banks.

“People were excited and engaged, and it made a huge difference,” Horn said.

Not unlike Beto O’Rourke in Texas, Horn took a granular approach to winning a district that had been considered the beating heart of the state Republican Party. She launched an aggressive ground campaign, going door to door as early as last summer in rural parts of the community where politicians didn’t usually make the effort. And she attended every public forum she could, sitting next to an empty chair when Russell, the incumbent, didn’t show up. Like O’Rourke, she ran as a progressive, but also as someone willing to rise above party to find solutions — an approach embraced by many of the winning Democrats on the ballot.

“When you have one-party control for over a decade and nothing good happens, people start to question whether or not that party’s best intentions are being acted upon,” said Alyssa Fisher, a programs manager at Sally’s List. “So there has been a lot of conversation, I think, even within some of the Democrats who won, courting Republicans, saying, ‘Look, I’m not here to bring a blue wave; I’m not here to radically change to your life — I’m just trying to bring a new level of conversation to the table where we can actually take action and change all the problems that we all see are real.’”

Russell tried to nationalize the race, tying Horn to House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and “liberal mobs,” but she responded at their one and only debate that Pelosi “wasn’t on the ballot.” She focused on education funding, health care and the state’s overcrowded prisons, and successfully dodged hot-button issues like abortion and immigration. On guns, she broke with Democrats who seek to ban on assault weapons and instead argued for a compromise that would ban high-capacity magazines.

And also like O’Rourke and other red state Democrats, she didn’t outwardly go after Trump. In fact, Horn barely mentioned him at all. While Trump was an issue “for many people,” she said, his presidency was just one of myriad issues that had “woken people up.”

While Horn was boosted by Oklahoma City’s shifting demographics, she won by peeling off some of Russell’s support in more conservative rural parts of the district. And that, she said, could serve as a good example for Democrats as the party grapples not just with an identity crisis as the 2020 campaign begins in earnest but also with the question of how to win back rural America.

In the ongoing intra-party debate about positioning for 2020, she comes down on the side of pragmatic centrism — a counterweight to the Democratic socialist wing represented by someone like New York’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “We need to be able to focus on what is best for our communities, our state, our country, and then party has to come after that,” she said. “I have said for a long time we have more in common [with political opponents] than we have differences, but we have to have a conversation with other people that we may not always agree with in order to find that out.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: