The ones that got away: Jonesboro's survivors — and the shooters — recall a moment of horror

It was five years ago that a young man invaded Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., and shot and killed 20 young children and six staff members, a tragedy that indelibly scarred that small city and lives on in the collective national memory. But school shootings didn’t begin, or end, with Sandy Hook. Yahoo News looks at the aftermath of four of these tragedies and the lives they changed. In this story, we examine how 20 years on, Jonesboro, Ark., is still traumatized by an attack carried out by two middle-school boys — and how survivors deal with the knowledge that the killers are now grown men and free from prison. In other stories we look at the lessons from Sandy Hook that may have helped save lives at a California school just last month and at how the parents of a girl killed in Newtown are coping with their loss.

_____

JONESBORO, Ark. — Sometimes the feeling of anguish comes out of nowhere. Maybe it’s triggered by a certain shift in the wind or when the temperature is warm but not too warm. Sometimes it’s seeing something on television that suddenly brings it all back, a memory of a horrible day that happened long ago but is as vivid as if it were yesterday.

For Lynette Thetford, it is the warmth of the early spring that has often proved to be most challenging, and for nearly two decades she has steeled herself waiting for those difficult days, bracing for the pain and memories that inevitably come rushing back no matter how much she prays to God for strength and healing, no matter how far she’s come.

Over the years, Thetford has gotten more adept at keeping it together, reliant on her strong Christian faith and protected by a cocoon of family, friends and colleagues who make sure she feels loved and safe. But last February, the darkness enveloped her when she wasn’t expecting it — an unusually mild day in the dead of the winter. It was the kind of day most people live for, especially the kids at Nettleton Junior High, where she works in the library. But in the early afternoon, Thetford felt her heart racing and her emotions plummeting. She struggled to breathe and tried not to cry. Soon she was over “the cliff,” as she put it, back in the emotional abyss.

Related slideshow: Paducah, Jonesboro, Columbine and Newtown: A chain of tragedy and grief >>>

“I wasn’t ready for it,” Thetford recalled, her voice a little shaky. “When it gets to the conditions of the air, when the weather was like it was that day — I know it’s been, like, 19 years, but I still have that relapse.”

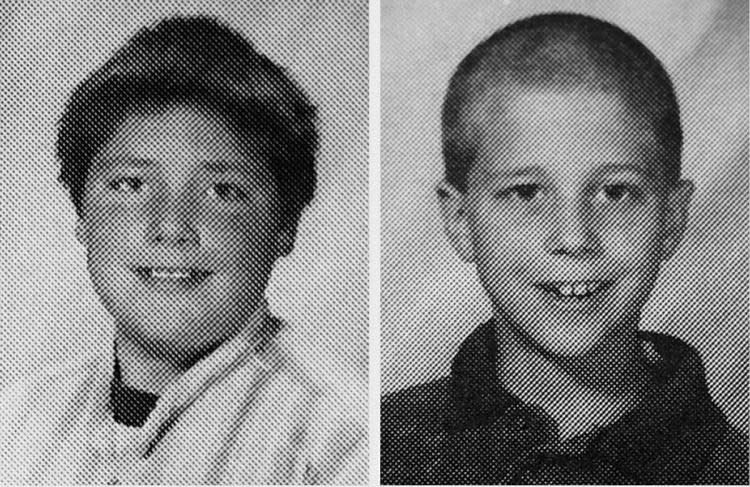

Thetford can’t help but think of another warm day, March 24, 1998, when she had walked out into the yard behind the nearby Westside Middle School, where she taught sixth-grade social studies. A fire alarm had gone off just after lunch, disrupting the beginning of fifth period. At first it wasn’t clear if it was a drill or a prank. It would turn out to be something far worse. As the students and teachers exited into the back schoolyard, gunfire rang out. From a makeshift sniper’s nest in woods behind the building, two students, Andrew Golden, 11, and Mitchell Johnson, 13, fired dozens of shots at their teachers and peers, using guns stolen that morning from Golden’s grandfather.

In a matter of minutes, the boys killed five people — four sixth-grade girls and a teacher — and injured 10 others, including Thetford, who was shot in the lower abdomen as she tried to steer those around her to safety. The bullet ripped through her intestines and severely injured the nerves that control her legs, causing her to fall forward to the ground unable to move. She was dragged to safety and kept from bleeding to death by colleagues who put pressure on her wound, but it took her months to learn how to walk again.

Related slideshow: Images from Newtown >>>

Before Columbine and Sandy Hook, before Sutherland Springs and Las Vegas and Orlando and San Bernardino and Charleston and Aurora and Virginia Tech and all the other mass shootings that have stunned and numbed the country over the past two decades, it was Jonesboro in the headlines, a small town that few outside of Arkansas had ever heard of. It was Jonesboro that horrified the nation and stripped away the innocence of teachers and students who had never imagined such evil descending on them, their school and their community.

***

What makes the Jonesboro case unique is that the shooters survived their rampage and have had the opportunity to explain but simply haven’t. Unlike other killers, such as Adam Lanza in Newtown and Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold in Columbine, Johnson and Golden didn’t turn their guns on themselves, which makes them a rarity among school shooters. The boys were apprehended as they ran away, toward a van packed with camping supplies and food for an apparent escape.

Each boy faced five counts of murder, which likely would have merited life in prison or even the death penalty had they been adults. But under Arkansas state law at the time, the two could only be charged as juveniles and held in jail only until they were 18, their records sealed. A little maneuvering allowed federal officials to add on three more years for weapons charges, keeping them in prison until they were 21.

In 2005, Johnson was released from prison after serving seven years, though he soon ran afoul of the law and briefly went back. In 2007, Golden was released and changed his name to Drew Grant — a detail uncovered only when he filed for a concealed weapons permit a year later. Arkansas State Police identified him through his fingerprints and denied the application. It wasn’t because of his criminal record — technically he didn’t have one, because the murder charges had been expunged. They rejected him because they said he wasn’t truthful on his application. Asked for his residential history, he had omitted the address of the correctional facility where he’d been locked up for years.

Because they were juveniles, their case remained largely shrouded in secrecy, and according to those close to the case, the boys declined to talk to investigators or offer any insight into what led to their deadly ambush. But they were forced to testify in a wrongful death civil case brought by the families and a hard-charging local attorney named Bobby McDaniel who was determined to seek answers from them.

In August 2017, hours of videotaped depositions of Johnson and Golden were released after a judge slapped the killers with a $150 million civil judgment — money the families do not expect to see. But they wanted the world to watch and learn from Jonesboro in hopes that their tragedy could produce lessons for other communities. According to McDaniel, they wanted do what they could to stop the tragedy from recurring and to offer something more enduring in the hopes that Jonesboro would be more than just another statistic.

“The real important aspect of this case is the why was it done, what did we learn from it, and how can we implement what we’ve learned?” McDaniel said.

In the testimony, which dates back nearly a decade, the public can hear and see the boys speaking for the first time about their crimes. The videos still offer no direct answer for the question “why?” The shooters, by then young men, largely blame each other for whose idea it was to ambush their school, as they did when they were first apprehended. Johnson claims Golden made him do it, and Golden testified that Johnson threatened to kill his family if he didn’t participate — dueling testimony that often rings hollow.

But Johnson seems more forthcoming than Golden about what led up to the shooting and what pushed him over the edge.

“I remember feeling like I was trapped, like no one understood me,” Johnson testified in 2007. “I felt cornered. I felt like I didn’t have anywhere to go, nothing to do. I thought my life, you know, was at an end. … I had a lot of people who were against me then.”

Johnson’s testimony included several dispassionate apologies to his victims. But echoing the little boy who felt the world was against him, he also sounds like a young man with his back against the wall, complaining of not being able to hold down a job because everybody knows who he is and what he did. “Society is cruel, you know, especially towards a murderer,” Johnson testified. “It’s just something I live with every day.”

Even in a churchgoing community where many believe in forgiving others as God has forgiven them, some survivors found Johnson’s comments chilling and hard to believe. The fact that he and Golden are free today disturbs and frightens many survivors. They worry about running into one or both and fret about the mindset of someone who may someday feel once again that the world is against him.

Though public records suggest both men now live out of state — Golden in Missouri and Johnson in Texas — some family members of the victims and survivors declined to speak about what happened in Jonesboro and their experience in the nearly two decades since, in part because they expressed fear of retaliation from the shooters. “Who knows what’s going on with them?” one said.

Nearly 20 years later, Thetford, who is 61, still sometimes limps, especially when she’s tired. And some days, in spite of her strong faith in God and her belief that she must have been spared for a reason, Thetford can’t help but feel tired. Tired of the guilt that never quite goes away and the shredded emotions that come with living through something that, back then, was not nearly as common as it feels today.

“I find myself glued to [the coverage],” said Karen Curtner, who was the principal at Westside during the shooting. “My husband’s like, ‘Why are you watching that? Don’t watch that.’ But what I find is … and I don’t know why I do this, but I try to figure out, I guess, some type of common denominator among all of these. That’s what I try to do. I analyze it, and I think, ‘What would cause a person to want to do that?’”

She’s not alone. Many Jonesboro survivors say they have obsessed over the details of shootings in other cities, looking at those tragedies as they still try to understand their own. Johnson and Golden have never explained exactly why they did what they did — a detail that has made finding a sense of closure much harder, if closure for something like this even really exists.

***

When it happened, the shooting ranked as one of the worst in the country’s history and the worst ever attack on a middle school, according to the FBI. Jonesboro, situated about 130 miles northeast of Little Rock, was inundated by media from all over the world, overwhelming the small city of some 50,000.

Located on the rural outskirts of town, amid rolling wooded hills that open up into flat farm fields of cotton and wheat, Westside suddenly found its parking lot crammed with satellite trucks. Producers from syndicated talk shows tried to sneak into the hospital rooms of survivors; reporters staked out funerals.

The idea that two baby-faced kids whose lives had barely begun had chosen to commit such a coldblooded and adult crime was a shocking and unimaginable concept — until a little over a year later, when Harris and Klebold, high school seniors, shot and killed 13 people and injured more than 20 others at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo.

After Columbine, Jonesboro slowly began to fade from the national spotlight. The white ribbons people tied on tree trunks in memory of the dead have long ago frayed and vanished. At Westside, where the school looks largely the same as it did 20 years ago, there is a stone bench out front carved with the date — “Mar. 24 1998” — and a small memorial in the shape of a sundial in a park area behind the building, near the sidewalks that were once stained with the blood of the fallen.

Engraved on the sundial are the victims’ names: Natalie Brooks, 12; Paige Herring, 12; Stephanie Johnson, 12; Britthney Varner, 11; and Shannon Wright, 32.

“Most of the kids who are here now have no idea what happened, what any of this means. They weren’t even alive,” a Westside teacher said on a recent Thursday afternoon after school had let out. “And to be honest, we don’t talk about it much either.”

That’s because the community has tried to move on. As at Columbine and Sandy Hook, the anniversary of the shooting was formally marked the first year or two. There was a ceremony around the flagpole in front of Westside to mark the five-year mark. Since then, the date has largely passed without mention, except for informal gatherings of family members and survivors — a decision encouraged by people who believed that moving forward was ultimately the best kind of healing for a town that had suffered so much.

But it is a tragedy that has quietly endured in ways that are not always so obvious — through the unimaginable loss still felt by parents and families of the children who were killed, the trauma and guilt that still plague the teachers, students and other survivors and other pain that has rippled in unusual ways through the community.

Everybody has a story — the responding paramedics and hospital staffers who were later diagnosed with PTSD, the counselors who tended to the victims who later needed counselors of their own to cope with what they’d heard, the teachers who walked away from the classroom forever because they couldn’t get past a sense of fear or guilt that they had been unable to protect their students from a threat that was not even near the top of the list of bad things that people here believed could happen.

“When we thought of safety back then, it was things like making sure that the playground was equipped with safety features,” said Curtner, the former Westside principal, who is now an assistant superintendent at Nettleton Public Schools, also in Jonesboro. “We never thought about people hurting other people. I guess I was naive.”

After the shooting, the parents of at least one child killed split up. Others took their surviving children and left town, trying to forge a new start in a new home and at a new school — though for some, it caused more anguish being in a community where there was no one to talk to about what they had been through. Some turned to alcohol or drugs to ease the pain. Others touched by the shooting have suffered serious health problems or died years before they were expected to, developments other survivors attribute to the enormous stress of what they went through. The children who lived through the attack are now adults with their own kids, and though many have been able to deal with the aftermath of that day much better than the grownups, some have told reporters about the fear they have felt in sending their own kids off to school, a place that no longer seems safe.

Many of the families and survivors no longer talk to reporters. Along with concerns about Johnson and Golden, some say the subject is too painful to talk about after all these years. Many are still angry at the media about how they were treated in the aftermath of the shooting. And others say they don’t want to be accused of trying to seek some kind of attention for themselves when some in the community have constantly urged them to “move on.”

After initially refusing to speak to the media or anyone else about what she had been through, in part because of survivor guilt, Thetford eventually saw the questions as a gift from God to lift the pain and burden she felt. She began speaking to reporters and at churches. After Columbine, she traveled to Littleton, where she met with survivors and others who were on the scene, including police officers, trying to ease their pain by sharing her own. As more acts of violence happened, she reached out to other victims of mass shootings, trying to offer comfort.

“I’ve written places and offered to come because when you hear about something like that, the first thing you want to do is put your arms around them and hug them,” she said. “That’s the first thing that comes to my mind is I just want to hold them and tell them it won’t ever be OK, but it’ll get better.”

***

Thetford knows she was one of the lucky ones, which comes with guilt all its own. She lived. After the hospital, she came home to her husband and her kids. And every year, it is she who takes a ski vacation with her family, who gets to hold her grandkids close and see them grow up. It is she who will finally retire this year, after nearly four decades as an educator, having refused to let one terrible day take away the job she had dreamt of doing since she was a little girl. “I count my blessings every day because I’ve been so fortunate,” Thetford said. But her life since has been anything but easy.

She still remembers the little details of that of that day, playing them over again and again in her mind. It was the second day back in class after spring break. Her husband had hit a deer with her old Monte Carlo earlier that morning, leaving a huge dent in the front. It was her dream car, and as she drove to work, she was upset. As she said hello to the secretaries in the front office, one asked her how she was doing. “The day can’t get much worse,” she replied.

Today, Thetford cringes at the remark. “I have not said that since,” she said.

Before class, she ran into her friend Shannon Wright, a sixth-grade English teacher who was one of the youngest on staff. Married with a 2-year-old son, she was showing off pictures of her family’s trip to Disney World the week before. “They were so bright and beautiful,” Thetford recalled.

When the fire alarm began blaring shortly after 12:30 p.m., a student told Thetford she thought she had seen Golden pull the alarm and run out the back door. Thetford was annoyed at the disruption. But she decided to do the drill anyway. Grabbing her grade book, she began walking her students down the hall toward the back exit. Along the way, she thought about Golden, who was one of her students. Thetford knew him and his parents well. His older sister had been in the first class she’d ever taught, and she’d also taught his brother, who was the same age as her son. Andrew, she thought, “is gonna be in so much trouble for pulling that fire alarm.”

Thetford was the first person out the back door into the warm sunshine. She began going down her class list, checking off the kids’ names. Around her, the yard was getting crowded with other students who had evacuated. That’s when she heard the first pops. It sounded like firecrackers, and she thought it was an ill-advised attempt to frighten the kids, perhaps to encourage them to take emergency drills more seriously. “What in the world is administration thinking?” Thetford thought.

Suddenly, Thetford began seeing students collapse around her, and she realized they were being shot at. Dropping her grade book, she began to frantically wave her arms. “Get down! Get down!” she screamed at those around her. Within seconds, she felt a “whoosh,” followed by horrific pain. She fell prone to the ground. On the sidewalk, she saw a little girl to her left. She had been shot in the head. “I knew she was dead,” Thetford said. Before she could come to grips with what she’d seen, she felt hands grabbing her and picking her up, taking her out of the line of fire.

Curtner came out the front door of the school. As she walked around the side of the building, she saw kids running in terror and others who were hurt and bleeding on the ground, including Thetford. She heard a series of pops.

For a second, she panicked. The school had practiced for fires, tornadoes and natural disasters. But they had never prepared for anything like this. They had no lockdown plan or security guard to protect them. “Schools were the safest place to be,” she said. “You never thought of needing anything like that. It was unheard of.”

The security doors leading back into the school were locked, a fire protection feature triggered by the alarm, so the principal began herding panicked kids and teachers toward the gym next door. Bullets were still flying, until suddenly the shooting just stopped. With little time to think, Curtner ran back to the front entrance, which was unlocked, and began racing through the classrooms grabbing giant buckets and supplies, including medical kits that they had prepared months earlier when scientists suggested a giant earthquake might hit the middle of the country.

She had no idea the crucial role those earthquake kits would play in another kind of disaster. Police and ambulances took more than 15 minutes to arrive at the school on the edge of town, and the kits were credited with saving the lives of several of the severely injured.

As ambulances arrived to transport the wounded, Curtner knew there were kids that didn’t make it. Nothing in her life had prepared her for what she saw as she ran around trying to assist. She tries not to think about it, but the images linger like a bad dream.

From the moment she began training to be a teacher, it had been drilled into her that she was responsible for keeping the kids in her care safe. If she could have stopped the bullets, she would have, but she hadn’t, and for that, she felt like a failure. But the pain and depression she would ultimately feel would only come much later. At that moment, she had the burden of taking on what needed to be done, of being the pillar of strength her kids and teachers needed.

Only when the police stopped Curtner and asked her to look through a list of students to mark who had been absent that day did she begin to wonder who had attacked her school. She wondered if it was a disgruntled parent or some mentally ill lunatic. But she checked off who had been out of school that day, a list that included Johnson and Golden.

“We’ve got these two in custody out in the car,” the officer told her, pointing to the boys’ names.

“For what?” she said.

Curtner didn’t get it, even when the officer told her Johnson and Golden had been found with the guns. And when it hit her, she couldn’t believe it. Later, people would ask her if the boys had been troublemakers, if there had been signs of instability or hints that they would become killers. Johnson had been in trouble, but nothing out of the ordinary for a boy his age. Even now, she remembers how unfailingly polite he was — always “Yes, ma’am” and “No, ma’am.” And she’d never even seen Golden in the office. “Not one time,” she said. She could not believe them capable of murder.

She knew their parents. The Goldens, who worked in the post office, had been involved with the school and seemed like good people. She was still thinking about it when Dennis Golden, Andrew’s father, rushed through the front door looking for his son.

“He thought he was coming to pick his child up. He’s like, ‘I can’t find my kid. Where’s my kid?’” Curtner recalled. “I remember them taking him in my office, and I remember the look on his face.”

Like Curtner, he was stunned.

***

The next few months were, according to Curtner, “a blur.” In a decision that perhaps wouldn’t be made today, classes resumed at Westside that Friday, three days after the shooting. The school administration, acting on the advice of counselors, had made the call in the belief that getting the kids back on a schedule would allow them to find “normalcy.”

The school had brought in high-pressure hoses to wash the blood away and tried to patch up bullet holes that had pierced the school building and the gym. They would ultimately bulldoze some of the trees where Golden and Johnson had set up their sniper’s nest and install fences designed to keep the grounds more secure, but that wouldn’t happen until later. Inside, the fire alarm had been temporarily deactivated, amid fears that a false alarm might send school into panic.

Some of the students didn’t return in those early days, but many did, even though that Friday also happened to be the day that many of the funerals were held. In every classroom, the state had assigned a counselor to encourage the kids to talk about their feelings, though many struggled to, or preferred talking only to teachers who, like them, had been there and could relate to what they were going through.

Nothing was normal. A police officer had been assigned to the building 24 hours a day, guarding what had become a macabre tourist attraction. Every day, there was more mail to open in what was an unbelievable outpouring of support. There were letters, teddy bears, school supplies and boxes of other gifts meant to help the school feel important. In classes, kids were assigned to write thank-you cards. It was just a struggle to get through each day.

“We just survived, pretty much,” Curtner said.

The following school year was trickier. Some of the teachers didn’t return — though after months of rehabilitation, Thetford did. She was happy to be back, happy to see her kids, but like every part of the journey after the shooting, it wasn’t easy. Many days, she spent time after school talking to Curtner and the other teachers in what became informal therapy sessions where they talked about the emotions and fears.

There were days when some of the staff couldn’t get out of bed because they were so depressed or full of anxiety. A few teachers admitted to thoughts of suicide. Thetford struggled with feeling guilty that she had survived while her friend Shannon Wright, who had taken two bullets while trying to shield her students, had died. And at one of her lowest points, Thetford told her mother, “I don’t understand why Shannon got to die, and I stayed here.” She was diagnosed with severe clinical depression.

That fall, the school was required to hold a fire drill. Some students and teachers decided to stay home rather than risk flashbacks. But Thetford knew she had to face her fears. Before the bell went off, she recalled how the new superintendent of the school district had approached her and grabbed her hand. “Mrs. Thetford, we’ll protect you,” he said.

“I thought, ‘No, he won’t. Nobody can protect you from things like that,’” she recalled.

While every day was a struggle, Thetford was determined to stick it out with her students. Instead of sixth-grade social studies, she was teaching the seventh graders, to allow her more contact with those who had been in school that day. She loved teaching history, she loved the school and she believed things would get easier. “To get me out of here, you’d have to blast me out,” she told a colleague.

But one day, she was pulling a clip of World War I for a lesson. She wanted to teach the kids about trench warfare, but she couldn’t bear to watch the film clip, because of the violence. How could she do her job without a visual? “I started crying,” she said. “That’s when I knew I’d have to get out of social studies.”

When the seventh-grade class that year moved on to the high school, Thetford took a job as a reading teacher at Nettleton and eventually went back to school to become a librarian. For her part, Curtner stayed with the kids, becoming principal of Westside High School, a job she kept until that class graduated. In a move that surprised her colleagues, she took a job as principal at the local high school for troubled youths. Explaining the move, she says she felt she could “make a difference.” But she also admits she felt she needed a change, and to deal with kids who had disciplinary issues felt easier than staying at Westside.

“I left that burden there,” she said. Moving to another school “took my mind off of it, and it was a saving thing for me.”

***

Frustrated by the secrecy of the juvenile court proceedings and the indication that the two boys who killed their kids would serve just a few years in prison, the victims’ families approached a prominent lawyer named Bobby McDaniel shortly after the shooting to ask if he thought there was any other avenue of justice.

Regarded as one of the best civil litigators in the state, McDaniel had made national news just two years earlier as the lawyer for Susan McDougal, one of Bill Clinton’s partners in the Whitewater land venture. McDaniel had forced the sitting president to sit for a deposition in a fraud case related to the failed real estate deal.

For him, taking the case was personal. Jonesboro was his hometown, and like everyone else he was horrified by what had happened. Nobody was in it for the money — except to prevent the boys from perhaps someday selling their stories or profiting off the crime. While the Golden family reportedly did pay an undisclosed amount of money to some of the victims’ families, what McDaniel and the parents really wanted was information. How could they stop something like this from ever happening to anyone again?

In 1998, McDaniel filed a wrongful death suit — naming Johnson and Golden as defendants, along with Sporting Goods Properties, the manufacturer of a Remington 742 rifle that was used by Johnson in the attack, arguing the gun was a risk because it didn’t have a trigger lock. While the gun company was later dropped from the case, in part because the guns were stolen, the attorney still said they had been successful, pointing to the increased presence of trigger locks that gun makers began to add to weapons amid worries of liability after what happened in Jonesboro.

“Every time you go into a gun store, every gun on a rack has a trigger lock on it. That was not the case when we filed this lawsuit,” McDaniel said.

But it took years to realize the other part of the case: trying to understand what made Johnson and Golden attack their school that day. It was nearly two years before he got to question the boys for the first time back in 2000 — testimony that was limited because they were still juveniles and Golden had filed an appeal to overturn his conviction, claiming he had been insane at the time of the shooting.

Then McDaniel had to wait again until the boys were out of prison. Because they had been held as juveniles, there was no reporting on their exact release or where they had gone. It took nearly a decade after the shooting to track them down and complete the depositions. It was another nine years before they were made public this past August — more than 19 years after the shooting.

“It was a long, long process, but as I told the families, and I maintained, the consequences of this case are gonna last lifetimes,” McDaniel said. “So what if we have to wait seven years, 10 years, 20 years. I will not abandon ship just because it’s gonna take a long time.”

The videos feel extraordinary — not so much for the answers they provide, but rather because they exist at all in a case that for years was marked by silence. It is rare to see killers speaking under oath about their crimes, even if some of the testimony offered by Johnson and Golden is hard to believe, including claims made by both that they had shot at the sky, not at people.

There are four separate videos of close to nine hours of testimony. Two of Johnson, one taken in 2000, when he was 15; and another in 2007, when he was 22 and soon to be on his way back to jail after being pulled over in a van with marijuana and an unregistered gun. (Johnson said it was a Christmas gift from a friend worried about his safety.) And two of Golden, one taken in 2000, when he was 13; and another in 2008, when he was 22. By then, Golden had changed his name to Drew Grant in an attempt to “start a new life,” he explained. McDaniel tracked him down after his failed attempt to get a concealed weapons license.

In the 2008 video, Golden appears nervous and uneasy. He talks about going to live with his sister in Missouri to change his name and start over and how he once stayed with a pastor of his parents to stay under the radar after his release. He had been taking classes at Arkansas State in Jonesboro under his new name and had been working odd jobs and relying heavily on his parents, who had bought him a truck and were paying for most of his expenses. He had gotten a single tattoo since he had left jail: a cross with the words “Roman 3:23.” When McDaniel asked which Bible verse it was, Golden mumbled, “For all who have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.”

Golden speaks of remorse, but never says he is sorry. He testified that he had never apologized or reached out to his victims on the advice of his lawyers and because he “didn’t want to stir anything up.” He delivers pages of testimony about his skills as an expert marksman, the awards he won as a child. But when asked about the shooting at Westside, he repeatedly testified he shot into the air or aimed at the gym, away from people, even though ballistics show bullets from his gun hit Thetford and killed Brooks, among others. It sparked a tense exchange with McDaniel, who, off camera, sounds increasingly incredulous.

Golden: “I didn’t ever intentionally shoot anyone.”

McDaniel: “That’s a lie, and you know it, isn’t it?”

Golden: “No, sir. I never aimed at anyone.”

McDaniel: “Oh, it’s purely coincidental that five people lay dead with bullets through their head and their hearts by pure accident, right?”

Golden: “I never intended to. I never shot at anybody. I didn’t.”

McDaniel: “Do you know what perjury is?”

But in a haunting moment, Johnson was asked during his 2007 deposition if he has read about the shootings that have come after Jonesboro, including the attack at Columbine, and what advice he might have to stop future killers like him. After a moment, he responded at length, speaking somewhat dispassionately about the warning signs to look for.

“If a person is normally active, a person is doing well in school and not having problems, and he just all the sudden clamps up, don’t want to talk, getting in trouble; obviously that’s a warning sign,” Johnson said. “Deviant behavior, running with the wrong crowd … that’s a bad thing. It is. People who are physically violent and don’t get counseling for it and don’t talk about it, don’t talk about their problems period, stuff boils over, you know.”

In the closest answer to a reason given by either one of the boys, Johnson added, “I think that was the main reason why. If there was any reason, that was the main reason why I decided to help Andrew do what he done, do we what done. I felt like I didn’t have anyone to talk to. I didn’t have anyone to open up to. I didn’t know who I could trust.”

According to public records, Johnson lives in Houston. Golden got married last year and lives outside Cape Girardeau, Mo. Neither one has ever personally apologized to their victims.

“I am incapable of expressing to you the stress, anxiety, frustration, and anger that these parents have that somebody who burglarizes a home, for example, or sells crack cocaine can get 40 years in prison, and these guys were out walking the street in virtually no time,” McDaniel said. “Just like we can’t lock up the drug problem — they tried that and it hadn’t worked — and locking these kids up for 100 years would be great at least in the eyes of the parents, but I don’t know the solution. There’s no answer that will remove their hurt, anger and frustration.”

***

On that warm day in February earlier this year, when Lynette Thetford felt all the pain and memories coming back, she excused herself from her desk at the Nettleton Junior High library and took a 15-minute drive back to Westside, down that winding road she has traveled so often over the past 20 years. She’s come here alone often or visited some of the students she lost at the cemetery up the street. But this time, she brought one of her assistants, a close friend who has seen her through dark times just like this one. She wanted to tell her the story of what happened that day.

As much as it hurts and will hurt, talking about it helps, crying about it helps. That’s what she tells other survivors of mass shootings and families who have lost loved ones. If Thetford had learned anything, it’s that keeping it all inside, bottled up, just doesn’t work.

When they got to the school, they walked down that sidewalk, where she was shot, where she saw little girls who had their whole lives before them cut down in an instant. She pointed to where the boys were, to where her friend Shannon Wright died protecting her students. She showed her the place where colleagues carried her out of the line of fire, where she lay on the ground, her colleagues plugging her wound and yelling at her to hang on.

There were so many thoughts going through her mind in those minutes after the shooting, weird ones that today she cannot explain. Was her house clean? Why had she just eaten that apple and banana for lunch instead of something better if that was going to be her last meal? As the minutes passed, she was more and more certain she was going to die right there. Wasn’t this the way it always was in the westerns she liked to watch. A bullet in the gut was deadly.

She worried about her husband and her kids and how she hadn’t been able to say goodbye to her parents. As she felt herself begin to slip out of consciousness, she saw that bright light people are always talking about. She was sure it was heaven. But something seemed to hold her back. Something in her heart told her she had to forgive whoever it was that did this to her and to her school. She had no idea who had fired those shots, but there on the ground she willed herself to forgive. She wouldn’t be a Christian if she only followed part of what Jesus said.

“I didn’t know it was the boys,” she recalled. “I was expecting big men in camo to come running around with the big guns in their hands. I never thought it was the kids. That was one of the biggest surprises.”

Thetford later woke up in the hospital. God, it seems, wasn’t done with her yet. The doctor told her she’d lost two 2-liter Coke bottles full of blood. She was lucky to be alive. Someone finally told her who had fired the guns. Andrew Golden and Mitchell Johnson. She thought of her deal with God. She had to forgive, and she had to keep forgiving.

Maybe that’s how a few weeks later she found herself comforting Golden’s parents, listening to his mother cry about how her baby was in jail downtown, so close, and she couldn’t hug him or hold him. The boy who had shot and nearly killed her. “I just cried. I cried with them,” she said.