Operation Cobra: The untold story of how a CIA officer trained a network of agents who found the Soviet missiles in Cuba

A strong southeasterly wind was whipping the surface of the Caribbean on the night of March 11, 1962, as the sport fishing boat approached the Cuban shoreline. The 30-foot Forest Johnson Prowler was one of the strongest, fastest wooden boats available, but its engine was quiet enough to allow its three crew members to bring it to within a mile of the shore. Those sailors were some of the most experienced mariners in the CIA’s small naval force of Cuban expatriates, but even they were not allowed to see the faces of the two hooded agents who clambered over the boat’s side into a 16-foot fiberglass canoe packed with supplies.

The rough sea almost ended the agents’ mission before it began, when their canoe capsized as soon as they got in, spilling its precious cargo of men and gear into the swelling ocean. The crew scrambled to retrieve the packages, which were waterproofed cans wrapped in plastic. With the canoe righted and the gear stowed again, the two agents climbed back in and managed to stay upright. Pointing the canoe toward the coast, they paddled off into the gaping mouth of the San Diego River.

The canoe had been the idea of Tom Hewitt, the agents’ case officer in the CIA’s huge Miami station, where he waited for word of the mission. Agency rules forbade him to take part in the team’s infiltration, but he felt a deep responsibility for the pair, a principal agent whom he had trained to manage a network of subagents, and his radio operator. It would be Hewitt’s job to guide their actions from afar, now that they were back in their homeland. A 10-year veteran of the CIA, Hewitt had spent the previous six months teaching the principal agent everything he knew about how to run an effective espionage network, doing all he could to mitigate the substantial risks that the agent would have to take in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. The team’s mission was to establish a network that could be used to gather intelligence and, if necessary, to foment counterrevolution against the Castro regime. Getting rid of Castro was a high priority for the administration of President John F. Kennedy and for the CIA. Hewitt knew this was an important mission, but he could not have imagined that his team would soon play a vital role in preventing nuclear Armageddon.

When the Soviets secretly deployed medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Cuba in the summer of 1962, it set off a chain of events that almost led to nuclear war. Scores of books and thousands of articles have been written about the Cuban missile crisis, yet Tom Hewitt’s name is absent from all of them. Photos of the missile sites taken by U-2 spy aircraft in October of that year are almost always cited as the key intelligence breakthrough that gave the United States a priceless advantage during the nuclear standoff. A Google search for “Tom Hewitt and Cuban missile crisis and CIA” turns up a single reference in a book by one of his old CIA bosses that refers to his role running “road-watch” teams during the United States’ secret war in Laos later in the decade.

As the years passed, the credit for finding the Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba was given largely to the U-2, with perhaps a few passing references to agent reports. The crisis was a turning point in intelligence history, after which senior U.S. government officials increasingly placed their trust in technical intelligence from spy planes, satellites and listening stations. Until now, however, the CIA has never publicly acknowledged Hewitt’s role in the mission that first spotted evidence of the missiles. “History just forgot about it,” said Jack Downing, a retired senior CIA officer who was friends with Hewitt for almost 30 years.

Timothy Naftali, a history professor at New York University and co-author of a book on the Cuban missile crisis, “One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro and Kennedy, 1958-1964,” said the documentation on Hewitt’s achievements sheds new light on the episode. “This is a big deal,” Naftali wrote when told about Hewitt’s involvement. The new information “helps explain the nature of the intel that forced the Kennedy administration to take a risk [by flying a U-2 over Cuba] that the president had wanted to avoid,” he said. The intelligence that persuaded the administration, he said, “had to be better than good.”

This Yahoo News investigation into the role Tom Hewitt and his agents played during the missile crisis has been pieced together from interviews with the Hewitt family and CIA veterans who served with Hewitt or knew him; Tom Hewitt’s personal papers, provided by his family; declassified CIA and other U.S. government documents; official Cuban government accounts; and books and news articles. Together, they tell a story of courage, commitment and quiet professionalism that changed the course of history.

Thomas Moses Hewitt III was born prematurely in Washington, D.C., in 1923 to poverty-stricken, soon-to-divorce parents. A sickly baby, he spent more than a year in the hospital as a charity patient. After a tough childhood, he entered the Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, N.Y., in the spring of 1943, at the height of World War II. On Feb. 22, 1944, Hewitt was serving as a cadet midshipman on the SS George Cleeve, a Liberty ship that was taking scrap iron from Tunis to Hampton Roads, Va., when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat 15 miles off the coast of Algeria. Hewitt and all but one of the crew survived but were forced to abandon ship.

After the war he married Mildred “Millie” Stewart, and in 1950, joined the CIA but left after six months because of what he later termed the “confining conditions” of his job in communications. “He liked people,” Millie said in a 2009 interview. “He didn’t like sitting in a little room decoding messages.” Following a series of professional setbacks, Hewitt rejoined the CIA in 1952, this time as a paramilitary officer. Based on his Kings Point education and his wartime experience at sea, the agency made him a maritime operations instructor at its new training facility at Camp Peary, Va., known as “the Farm.” He and Millie then spent two years in Istanbul before returning to headquarters. But Tom soon got bored working on the India desk and requested reassignment to the CIA’s burgeoning Miami station. The Hewitts, now with their 1-year-old son, Tim, in tow, arrived in Miami in early 1961.

For a CIA officer looking to make his mark in the early 1960s, there was no better posting. In 1959, Fidel Castro had overthrown the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista and installed himself atop an increasingly communist regime in Havana. The Cold War was at its peak, and the Kennedy administration that took office in January 1961 was determined to be rid of the first communist government in the Western Hemisphere. As Castro’s policies squeezed the Cuban middle and upper classes, thousands of Cubans fled to Florida, many hoping to launch a counterrevolution to liberate their homeland. But the first serious effort to accomplish that goal failed in spectacular fashion in April 1961, when a brigade of CIA-trained Cuban exiles landing on a beach in southern Cuba’s Bay of Pigs was easily defeated by a vastly superior Cuban military force. The fiasco humiliated President Kennedy and his brother Robert F. Kennedy, the attorney general, and left them hungry for revenge and determined to unseat Castro. But it also left a residue of mistrust between the new administration and the CIA.

The center of U.S. anti-Castro activity was Miami, a city now teeming with Cuban exiles, who had formed dozens of counterrevolutionary groups. The CIA had established what would soon become the agency’s largest station outside its new headquarters in Langley, Va. Codenamed JMWAVE and located on land owned by the University of Miami, the station was manned by hundreds of agency employees and contractors who worked under the flimsy cover of “Zenith Technical Enterprises.”

It was from here that the CIA ran its secret war in Cuba. U.S. policy prohibited the agency from parachuting agents into Cuba, so it used a fleet of small boats — crewed mostly by Cuban exiles — to slip them onto the island. But Cuban security forces patrolled the coastline on land and at sea, and the Soviets had helped the Castro regime to install interlocking radar stations along the north coast, making it increasingly difficult to smuggle people and materiel into the country. Few CIA case officers had the experience required to conduct successful maritime operations in this environment. Tom Hewitt was one who did.

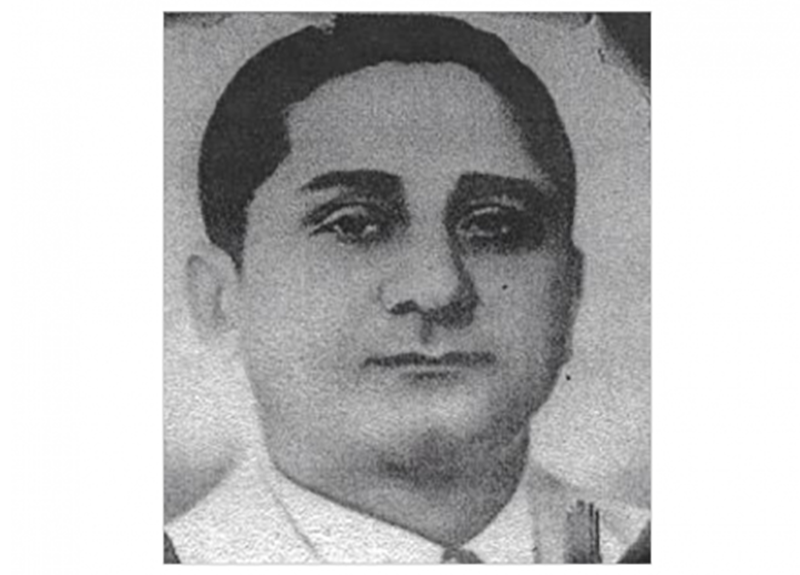

In April 1961, as the Hewitts were settling into their new home in the Miami neighborhood of Coral Gables, 51-year-old Esteban Márquez Novo was taking refuge in the Argentine Embassy in Havana. Born in Los Palacios, in western Cuba’s Pinar del Río province, to a well-to-do family, Márquez Novo was a former member of the Cuban army under Batista. With Castro’s ascent to power, the fiercely anti-communist Márquez Novo took up arms against the new government with a group of other former Batista soldiers. According to Granma, the official newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party’s Central Committee, Márquez Novo launched his revolt on Feb. 19, 1961, from the Sierra del Rosario mountains in Pinar del Río province. It was a short-lived rebellion. Castro militias soon captured several members of Márquez Novo’s group. In early April, Márquez Novo came down out of the mountains and slipped into Havana, where he sought political asylum at the Argentine Embassy.

Argentina granted his request, and after almost seven weeks in the embassy, Márquez Novo left Cuba on a flight to Caracas, Venezuela, supposedly en route to Argentina. But his plans changed after a visit to the U.S. Embassy in the Venezuelan capital. The CIA, which had been alerted to Márquez Novo’s departure from Cuba, flew him to the United States.

In Miami, Márquez Novo was met by Hewitt, who took him to a safe house where he was kept isolated for roughly two months while the CIA officer debriefed him and assessed his potential as a CIA agent to be infiltrated back into Cuba. Concluding that even in middle age, Márquez Novo was a suitable agent candidate, Hewitt formally recruited him and began an intensive six months of training in what the CIA officer later referred to as “clandestine operational procedures.” During this period, Hewitt paired Márquez Novo with another Cuban exile called Yeyo Napoleon, likely a pseudonym, who was to be his radio operator and thus had to go through much of the same training.

Hewitt — whom his agents knew only as “Otto” — took a hands-on approach to the training, something he believed was essential in order to evaluate and establish rapport with Márquez Novo, whom he called “Charlie.” Basic instruction in radio skills, weapons and secret writing was provided by specialists in those subjects with Hewitt present. But Hewitt personally conducted all other training in espionage tradecraft. Márquez Novo and Napoleon could have had no better instructor, according to Jack Downing, who served as the CIA’s deputy director for operations — the agency’s top spy — from 1997 to 1999. Not only was Hewitt “omnicompetent” when it came to “basic survival skills,” he was also “a very cool customer,” said the veteran CIA operative. “If someone said to me, ‘You’re going into this jungle, or your plane is going to be shot down over this territory, who do you want at your side?’ my first choice would be Tom. … He was the last guy that would ever panic in a flap.”

But teaching his Cuban agents the best tradecraft in the world would count for nothing unless Hewitt could successfully get them back to their homeland.

The first step in planning the infiltration was to pick a spot on the Cuban coastline where Márquez Novo and Napoleon could sneak ashore. Together with Márquez Novo, Hewitt picked a location not on Cuba’s northern coastline, which was easiest to reach from Florida, but on the southern coast of Pinar del Río province, 2 miles up the San Diego River, which emptied into the Caribbean in the Gulf of Batabanó. It was a place that Márquez Novo knew well and felt secure with, Hewitt later wrote.

But getting there would require a round trip of at least 1,400 miles, and a boat with a maximum draft of 5 feet to allow it to negotiate the shallows between a string of islands called Cayos de San Felipe and the much larger Isle of Pines. Once close to shore, Hewitt wanted Márquez Novo and Napoleon to paddle a fiberglass canoe loaded with 300 pounds of supplies up the river to the infiltration point.

When Hewitt outlined his concept to other case officers in Miami, they thought he was “crazy,” according to Rudy Enders, an agency paramilitary officer who worked closely with Hewitt in Miami, and who later ran the CIA’s Special Operations Group. The station didn’t own any boats with such a shallow draft that had anything like the range necessary for the round trip. Only one officer in Miami supported Hewitt: Enders, who, like Hewitt, was a Merchant Marine Academy graduate. “I thought it could be done easily,” the latter wrote in an unpublished account that he shared with Yahoo News.

The plan that Enders and Hewitt proposed was to use a World War II landing craft

to tow a Forest Johnson Prowler around the western tip of Cuba to within 10 miles of the Cayos de San Felipe. Even though it could only travel at 10 nautical miles per hour, the landing craft was reliable and had the range needed. The Prowler had a draft of 4.5 feet, meaning that it could safely traverse the shallows between the Cayos de San Felipe and the Isle of Pines. Close to shore, the Prowler crew could put the canoe into the water, load it with supplies and send the agents on their way.

Senior officers in the Miami station greeted Enders’s proposal with skepticism.

Hewitt and Enders needed the approval of one particular officer, Rocky Farnsworth, the station’s chief, before they could put their plan into action. Unable to get a meeting, Enders cornered him in the men’s room. “While pissing, I told him the idea would work, and if it didn’t, I’d quit,” Enders wrote. Farnsworth agreed to go forward with the plan, contingent on a successful sea test of the concept.

The test was “flawless,” according to Enders, who had designed a special harness to tow the Prowler. The operation got the green light. The case officers and the agents made final preparations. Among the supplies Hewitt was sending his team in with were two RS-1 radios, personal weapons, maps and cash.

The infiltration was to be known as Operation Cobra; the spot on the banks of the San Diego where the agents were to make landfall was Site Helen. The CIA also gave the agents cryptonyms for use in all communications: Esteban Márquez Novo was AMBANTY-1, Yeyo Napoleon was AMBANTY-2. (The AM digraph preceded all CIA Cuba-related codenames.)

Enders assembled an all-Cuban crew for the mission. The landing craft’s captain and first mate had each been professional sailors for a steamship company before the revolution. Although they had no military experience, they volunteered their services to oppose Castro, and each survived the traumatic experience of captaining a ship into the Bay of Pigs, only to have it sunk. “These relatively elderly men proved willing to take great risks for the liberation of Cuba,” said Enders. “One had to respect and admire them.”

The landing craft left Key West and rendezvoused with the Prowler at the Sand Key Lighthouse about 8 miles out to sea. From there, the three-day voyage around the western end of Cuba was uneventful, with the captain making sure he stayed in international waters throughout. But the captain’s nerve faltered as he approached the Cayos de San Felipe, and he released the Forest Johnson Prowler 10 miles farther out to sea than he was supposed to. Nonetheless, the wooden boat’s three crewmen were able to sail it to the canoe drop-off point without incident, and Márquez Novo and Napoleon paddled away. They reached the broad mouth of the San Diego river and kept going for a couple of miles before they found the right place to come ashore. After unloading the supplies and caching them near the river bank, they sank the canoe in such a fashion that it could be used again. Then Márquez Novo and Napoleon slipped away into the night.

“The operation was classic,” Enders later wrote in a letter to Millie Hewitt. “We proved the skeptics wrong.”

Márquez Novo and Napoleon immediately got to work. “The two-man team was given the mission of contacting any existing underground organization, establishing radio contact with the Miami base, developing a maritime channel for infiltration/exfiltration operations, and providing intelligence on the local situation,” Hewitt later wrote.

With his previous contacts in the anti-Castro resistance, his familiarity with the region and a large family that he used as a source of recruits, it did not take Márquez Novo long to gain traction in Pinar del Río. In the months following his infiltration, he steadily built up his network, which he named the Frente Unido Occidental (FUO), or United Western Front.

Relying heavily on the tradecraft that Tom Hewitt had drilled into him, Márquez Novo made sure that his couriers always moved cross-country, never on roads or trails, and used concealment devices on women or animals for carrying messages. The FUO persuaded sympathetic locals to employ a system of visual signals to warn its members of safety or danger by hanging different colored clothing on their clotheslines. Supplies were either buried or carefully concealed in cover.

As the network expanded beyond friends and relatives to include sources in the police and the militia, Márquez Novo communicated with his subagents via a courier answerable only to him. He checked the identities of all potential agents with the Miami station before recruiting them, and even kept Napoleon under close watch. The FUO tapped the phone lines of Castro militia and coast guard posts. Márquez Novo, who adopted the alias “Placido,” maintained a separate unit of scouts in rural districts whose job it was to lead his teams through those areas safely. The network also had a counterintelligence force that vetted recruits and investigated security breaches.

These techniques all served to make Márquez Novo’s efforts extraordinarily successful at first. “From the nucleus of the original two-man team, the operation developed into an extensive resistance/intelligence complex extending throughout Pinar del Río, with branches covering Havana and the Isle of Pines,” Hewitt wrote.

The maritime operations that allowed for the resupply of the network and the occasional exfiltration of agents for training proved key.

The first such mission occurred on May 24, 1962, when, despite a close call with a Cuban patrol craft, the CIA ran the first successful maritime resupply operation for the AMBANTY network, delivering about 1,500 pounds of weapons and miscellaneous supplies to Site Helen, the infiltration spot on the bank of the San Diego River.

Soon the network was attracting high-level attention in the U.S. government. Army Brig. Gen. Edward Lansdale, who was in charge of Operation Mongoose, the Kennedy administration’s campaign to destabilize Cuba and overthrow Castro, noted in a July 25, 1962, memo that of the 11 teams that the CIA had infiltrated into Cuba, “the most successful is the one in Pinar del Río.” But decisions being made half a world away were about to raise Márquez Novo and his agents to a position of even greater prominence.

On Aug. 1, 1962, an agent reported some very unusual events in the Pinar del Río port of Mariel. A large Soviet vessel had arrived that day under conditions of extraordinary secrecy. “No one was allowed near the vessel, not even the customs officials,” the agent reported. “Cargo unloading of the vessel began after all regular employees of the port area were sent away.”

“A large number” of what the agent thought were “Chinese, Czechs and Soviets” disembarked from the ship, although the “Chinese” were probably Soviet personnel from the USSR’s Far Eastern territories. Trucks were then hoisted aboard the boat and lowered into the holds, where they were loaded and covered with canvas before being “swung ashore in a very careful manner, as though they were made of glass.” Once ashore, the trucks were driven off under the guard of Soviet personnel. The agent then added a compelling comment: “It is probable that the trucks were loaded with rockets, nose cones for rockets, or most probably atomic bombs.”

The agent was closer than almost anyone in the CIA headquarters gave him credit for.

In the summer of 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev took a gamble that almost nobody in the West anticipated: He ordered the deployment of medium and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles to Cuba. The Soviets’ arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles did not compare with that of the United States. But medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba could make up for that shortfall by placing U.S. cities at risk. If the Soviets could get the missiles in place and operational before the United States realized what they were up to, they could present the United States with a fait accompli, giving the communist superpower enormous leverage in future negotiations by allowing it to hold American cities hostage.

But installing medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in a country separated from the Soviet Union by an ocean and a continent was not going be accomplished overnight. It required the deployment of thousands of troops, the construction of missile bases, and the deployment and installation of SA-2 anti-aircraft missiles to defend those bases. The final steps involved shipping the ballistic missiles themselves and their nuclear warheads.

The initial stages of this buildup were reported by Hewitt’s AMBANTY network in western Cuba, by agents in Las Villas and Matanzas provinces reporting to Hewitt’s close friend Gene Norwinski, and by newly arrived Cuban refugees who were cycled through a screening facility in the Miami neighborhood of Opa-locka, run jointly by the CIA and the military. An Aug. 20 memo from CIA director John McCone mentions receiving “approximately 60 reports” on “stepped up” Soviet bloc military support of Cuba.

Esteban Márquez Novo and his group were now proving their worth. An undated timeline history of the AMBANTY network written by Hewitt, and reviewed by Yahoo News, contains one line that reads simply: “Summer 1962 — Missile Crisis Building — Reporting Missile Site Preparations.”

However, as the reports from the agents in Cuba reached Langley, they ran into a wall of skepticism. There was an overriding belief among CIA analysts that the Soviets wouldn’t dare deploy ballistic missiles to Cuba, which critics later suggested made them irrationally skeptical of reports to the contrary.

Meanwhile, nervousness on the part of senior U.S. officials would soon deprive the United States of its other “eyes” on Cuba – those of the CIA’s U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. The CIA had been flying U-2s over Cuba twice a month since February 1962 without incident, but photographs taken during an Aug. 29 flight revealed the presence of at least eight SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites in the western part of the island. The SA-2 was the same type of missile that had shot down the U-2 flown by the American pilot Gary Powers over the Soviet Union in May 1960. The Soviets were deploying it to Cuba to prevent the United States from learning about the nuclear ballistic missiles that were to follow.

Wanting to avoid a repeat of the Powers incident, senior U.S. officials redrew the path of the next overflight, scheduled for Sept. 5, so that it avoided western Cuba. On Sept. 11, Kennedy signed off on a plan that would cut the next flight into four pieces and keep the U-2s from flying over western Cuba entirely. Now the only eyes on the Soviet buildup in Pinar del Río would belong to Hewitt’s agents.

But even after the Soviets began installing the SA-2s, the CIA’s analysts refused to believe that the Soviets were about to deploy medium or intermediate-range ballistic missiles. The only senior CIA official to give serious credence to that notion was the director himself. However, in late August, McCone took off to France on a honeymoon with his new bride and did not return for several weeks. Now, the one senior U.S. official who believed that the Soviets were likely to deploy ballistic missiles into Cuba was abroad as the debate played out in Langley.

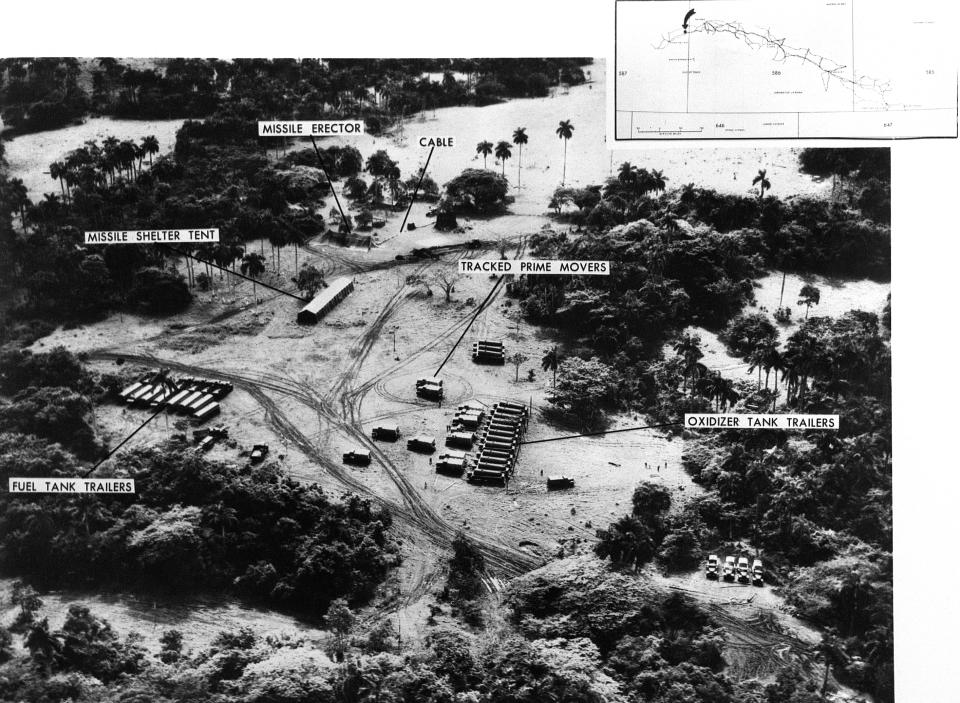

Even as the CIA’s Office of National Estimates was putting the finishing touches on a document that predicted that the Soviet Union was unlikely to deploy medium-range ballistic missiles to Cuba, the AMBANTY network was sending the message to Miami that would ultimately disprove it. The agents’ report, which the CIA circulated on Sept. 18, 1962, said that a large area in central Pinar del Río province “is heavily guarded by Soviets with the assistance of Peruvian and Colombian nationals.” In particular, the report highlighted heavy security that prevented access to the Cortina finca, or country estate, near La Güira, “where very secret and important work is in progress, believed to be concerned with missiles.” The report gave the grid locations for the four small towns that marked the boundaries of the area. “If you take a pencil and hook up these four towns with a pencil line, you find yourself with a trapezoid,” said Samuel Halpern, a CIA officer who was working on Cuba issues at Langley, in an unaired segment of an interview conducted for the 1998 CNN series “The Cold War.” “And so it became known as a trapezoid area, and that was the area we finally got the U-2 to be allowed to fly over.”

On Oct. 14, a U-2 reconnaissance plane flown by Air Force Maj. Richard Heyser traversed western Cuba, taking hundreds of photos of the area pinpointed by the AMBANTY network. By Oct. 16, those photos had been analyzed. They revealed exactly what Hewitt’s agents had reported, the presence of medium-range ballistic missiles. President Kennedy now had visual proof he could show to the rest of the world that the Soviets were deploying offensive missiles to Cuba. Crucially, he also knew the missiles were not yet operational, depriving Khrushchev of a critical advantage in any negotiations that might follow. For six days, Kennedy huddled with his advisers, considering options that ranged from a full-scale invasion of Cuba to simply accepting the Soviet deployment. On Oct. 22, the president addressed the nation, informing the American people — and the world — about the missile sites and explaining that the U.S. Navy would blockade Cuba to prevent any further buildup. For almost a week, the world held its collective breath as Kennedy and Khrushchev engaged in a contest of wills with the fate of their countries in the balance.

For Esteban Márquez Novo and the rest of the AMBANTY network, the operation was a entering a dangerous new phase. As the crisis built, according to Granma, the Cuban Communist Party newspaper, Márquez Novo was holed up with Napoleon in a safe house about 3 miles from the village of Entronque de Herradura in Pinar del Río province. In one of Hewitt’s timeline histories, there is a simple one-line entry: “Missile Crisis – Agent jumps to prominent importance.” The network also reported that month on Soviet installations on the Isle of Pines and on Soviet ships entering Mariel and Havana harbors, Hewitt wrote. The agents were taking significant risks, and according to Hewitt, one leader was arrested on Oct. 10 and sentenced to five years in prison.

On Oct. 28, Khrushchev announced on Radio Moscow that the Soviets would remove their missiles from Cuba. Kennedy quickly accepted his offer, agreeing privately to withdraw the United States’ Jupiter missiles from Turkey. Kennedy also pledged publicly not to interfere in Cuba’s internal affairs and to respect Cuba’s sovereignty and the inviolability of its borders. From their safe house, Márquez Novo and Napoleon watched the Soviet forces withdraw with their missiles. The crisis was over, but for the AMBANTY network, even darker days lay ahead.

By the fall of 1963, Márquez Novo was becoming impatient. He had built a large resistance organization, but the CIA refused his requests to undertake guerrilla warfare against the Castro regime. On Nov. 15, he sent a coded message via radio to Hewitt: “I will have to decide between on [sic] insurrection and departing Cuba. I have decided on insurrection. I hope you will help me with the weapons I need.”

Hewitt replied the next day. “As you agreed when you were here, there can be no insurrection in Cuba until it can take place simultaneously throughout Cuba. Such a total uprising is not possible at this time.” He reinforced the point with another message sent the same day: “If you insist on precipitant action before the whole plan is ready you are going to draw all the enemy forces down upon you and the people of Pinar, which will result in the complete destruction of everything you and your men have labored so hard to create. We cannot support an insurrection now. We will continue to support you and group as agreed upon.”

The size and structure of the United Western Front was becoming something of a vulnerability for Márquez Novo. His organization was created for guerrilla warfare, but all it was doing was collecting intelligence. “The two are essentially not compatible,” Rudy Enders wrote in an email to Yahoo News. “Carrying out the first objective requires bringing in large numbers that are sure to become penetrated by Cuban intelligence agents, whereas intelligence collection units are composed of small three- or four-man cells that are highly compartmented.”

Meanwhile, the KGB was helping to professionalize Castro’s security forces. The lax control that had characterized the operational environment when Márquez Novo was infiltrated had morphed by 1964 into a much more authoritarian system, according to Hewitt. Anyone who did not join the Communist Party or another mass organization immediately became suspect in the eyes of the regime. Castro’s counterintelligence organizations had developed a patient approach when investigating suspected anti-government activity and would offer people arrested on anti-government charges freedom if they agreed to become informants.

It became increasingly difficult for the CIA to infiltrate agents into Cuba, and increasingly dangerous for those who made it in.

It was inevitable that a network like the FUO, which some estimates put at up to a thousand strong, would eventually be penetrated. But the AMBANTY network made it easier than it needed to be for the regime by routinely and needlessly breaking numerous cardinal rules of espionage. In essence, according to Hewitt, the Cuban agents couldn’t keep secrets. Some agents suffered from what Hewitt termed a “compulsion to confide with any trusted friend or relative details [of] their underground activities.” They would sometimes wear or carry openly equipment that was supposed to be used “only for underground work,” he said. Agents would contact potential recruits in their own home, and people who had not been formally recruited were nevertheless brought in to assist with operations. Márquez Novo himself sometimes failed to fully assess the motivations of individuals he recruited, saddling the network with what Hewitt described as “some rather reluctant agents.”

But Hewitt was also critical of U.S. government policy toward clandestine operations in Cuba, which “blew hot and cold,” he wrote. There was, he added, “no consistent plan for developing country-wide resistance.” Without naming names, Hewitt suggested that the United States was pushing the FUO too hard. “Pressure for results for internal network very heavy from above,” he wrote. Sometimes the CIA itself was at fault, running two networks in the same geographic area, with the result that both were compromised, he added.

Márquez Novo and the CIA had been pushing their luck for two years with the AMBANTY network. In the spring of 1964, that luck began to run out. “The first indication that the net was in danger of roll-up came with the arrest of one of the agency-trained assets on 4 February 1964 in Paso Real, central Pinar del Rio,” Hewitt wrote. “The individual was apparently arrested in a routine round-up of counterrevolutionary suspects, but he was moved to Havana and eventually executed on 15 April.”

On May 15, a coal delivery man visiting a farm near San Juan y Martinez in Pinar del Río stumbled upon a buried cache of munitions and communications gear, according to Granma. He alerted the security forces, who searched a nearby hut and found a briefcase containing what the paper described as “a spy’s diary, intelligence information, instructions and messages from ‘Otto’ to ‘Placido.’”

Within 48 hours, they had arrested one of the network’s principal agents, according to Hewitt. “On the same day, BANTY-1 closed down his communications with the Miami base by informing the base that he would reopen when the local situation had been clarified,” Hewitt said. “He never came back on the air.”

By now, Cuban security forces were descending on homes and safe houses across western Cuba and the Isle of Pines, arresting hundreds of the network’s members. One of those detained, according to Granma, told his captors that “Placido” – Márquez Novo – was holed up in a tobacco house in Entronque de Herradura.

Accounts differ as to what happened next. According to Granma, on May 20, security personnel surrounded the building. Márquez Novo torched the documents he had with him rather than have them fall into his enemies’ hands, and decided to go down fighting, shooting at the security forces. When they finally forced their way inside, according to the Communist newspaper, they found Márquez Novo dead of an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound to the temple, beside a briefcase containing $10,000, 215 pesos in gold coins and almost 44,000 pesos in cash.

Márquez Novo’s niece, Aracelis Rodríguez San Román, told the story with a different twist when interviewed by the Miami Herald 10 years ago. In her version, her brother Gilberto, Márquez Novo’s nephew, who had just been reinfiltrated a week previously, had been killed in a gunfight with Cuban troops. When Márquez Novo learned of Gilberto’s death, he shot himself, Rodríguez San Román told the Herald. (Rodríguez San Román, who according to the Miami Herald was the FUO’s bookkeeper, declined to speak with Yahoo News, but her nephew Guillermo Castilla said his family was only familiar with the version of events in which Márquez Novo took his own life.)

Hewitt’s account of Márquez Novo’s demise is darker: BANTY-1 was “beaten to death” by Cuban intelligence.

One of Márquez Novo’s last radio messages to Hewitt, according to both Granma and an account by Fabián Escalante, a former senior Cuban counterintelligence official, read as follows: “Today is the second anniversary of the founding of the FUO, and I am confident that my labors during this time have been of some use to our cause. … A toast, a toast with whiskey or champagne, while I and my men dry our tears with blood-soaked handkerchiefs.”

By the time the Castro regime rolled up the AMBANTY network, the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the looming war in Southeast Asia had sapped the CIA’s Cuba project of much of its bureaucratic energy.

As the United States’ anti-Communist focus shifted to Indochina, so too did many Miami station personnel. Hewitt served in the United States’ secret war in Laos in the mid-1960s, then did a tour in Vietnam before spending his final years of service working as a CIA liaison to the Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg, N.C. There, he helped Army Col. Charles Beckwith establish Delta Force, the Army’s premier counterterrorist unit.

After a 30-year career in the shadows, Hewitt took early retirement from the CIA in 1981 to spend more time with his son, Tim, who had been seriously injured in a car accident. Tom Hewitt was never promoted to senior management at the CIA. He died of cancer in 1997 in relative obscurity, convinced until the end that the organization to which he had devoted three decades of his life had not fully recognized the most important contribution he had made during that time.

On Oct. 1, 2004, the phone rang in Millie Hewitt’s apartment in McLean, Va. A woman from the CIA protocol office was on the other end of the line. She said she was calling to tell Millie that the agency had decided to posthumously honor her late husband with the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, the agency’s highest award, for his work during the Cuban missile crisis. Millie was so shocked she thought it might have been a crank call, according to Tim’s wife, Pam. But the call was real.

About six years after Hewitt’s death, for reasons that remain unclear, Bob Wall, who had been Hewitt’s immediate supervisor in Miami and had also served with him at the Farm and in Vietnam, started a campaign to get the CIA to recognize Tom Hewitt’s role in the missile crisis. He even wrote to CIA director George Tenet urging him to give Hewitt an award. Personnel in the agency’s Latin American division began to investigate. For nine months, they pored over documents pulled from old files, gradually assembling the evidence to support Wall’s contentions.

On a cold January day in 2005, about 30 visitors gathered in a large, sterile conference room in what is known as “the old headquarters building” on the CIA campus in Langley to honor Hewitt. The guests were mostly family members and friends of the Hewitts. Only a couple of Miami station veterans were there: Bob Wall, without whom the award would not have happened, and Gene Norwinski, the case officer who had run teams of agents in central Cuba that had also reported on the presence of Soviet missiles. Usually, a senior CIA official would make the presentation. But coming so long after the events that prompted it, this was no usual award. Millie, who died in 2017, had requested that the award be made by Jack Downing, the retired senior CIA official who had been a friend of the Hewitts since 1969. Downing presented Millie with a folder containing the large bronze medal, together with a citation that in one paragraph appeared to rewrite the history of the Cuban missile crisis:

“In January 1961, Mr. Hewitt joined the Miami Station as a Paramilitary Officer in the Cuban program. Shortly thereafter he developed and ran one of the most successful operations in the history of the organization. Mr. Hewitt spotted, developed, recruited, and provided intensive paramilitary training to a team that was infiltrated into Cuba. It was this team that reported on the presence of nuclear equipment in the Pinar Del Rio Province of Cuba. Based upon the reporting from Mr. Hewitt’s team, U-2 aircraft were dispatched to the region. Their photographs confirmed the presence of nuclear capable missile equipment. The rest is history, known today as the ‘Cuban Missile Crisis.’ Public credit for the discovery of the missiles in Cuba was given to the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft in order to preserve the security of the team that Mr. Hewitt created, trained, managed, and motivated through one of the darkest periods of the Cold War. … It was his commitment to the mission, dedication, and obligation to the agents he ran in Cuba that resulted in the collection of intelligence that impacted on the course of history.”

CIA spokeswoman Sara Lichterman reiterated this message when questioned for this story by Yahoo News. “It takes the ingenuity and courage of people like Tom Hewitt — who serve not for glory or recognition, but for duty and love of country — to change the course of history,” she wrote. “We are grateful to his colleague for drawing attention to the full impact of Hewitt’s contributions, spurring the Agency to award him its highest honor, the Distinguished Intelligence Medal.”

Tom Hewitt’s son, Tim, was in high school when his father told him about his achievement during the missile crisis. “He said his team discovered the missiles, but he never got credit for it,” Tim said.

In an odd way, Hewitt’s own professionalism may have been partly to blame for the length of time that it took the CIA to recognize his exploits and those of his network. “The thing I always heard was Dad had a very secure operation,” Tim said. “That’s why it took so long to come out.”

Tom Hewitt took the need-to-know principle seriously, even when it came to Jack Downing, who as the CIA’s deputy director for operations held almost every security clearance possible by the time his friend died. “Tom, during a friendship of almost 30 years, never disclosed this operation to me,” Downing told the small crowd at Hewitt’s award ceremony at Langley.

To the last, it would appear, Tom Hewitt adhered to the motto of his alma mater, the Merchant Marine Academy: “Acta non verba” — deeds, not words.

*Lead photo caption/credits: President John F. Kennedy addresses the nation on television, Oct. 22, 1962, in Washington, D.C., announcing a naval blockade of Cuba until Soviet missiles are removed; CIA case officer Tom Hewitt; President Fidel Castro of Cuba replies to President Kennedy’s naval blockade on Cuban radio and television on Oct. 23, 1962; Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1960; foreground: Kennedy meets U.S. Army officials during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962; (background) aerial reconnaissance photo showing a missile launch site in San Cristobal, Cuba, on Oct. 23, 1962. (Photos: AP, courtesy Hewitt Family, AP(2), foreground: Corbis via Getty Images; background: Bettmann Archives via Getty Images)

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

House ‘will open up money-laundering inquiry’ into Trump-Russia ties

Will the House Progressive Caucus play ball — or hardball — with Pelosi?

PHOTOS: Furloughed federal workers protest Trump’s government shutdown