Opioid-law scandal sheds light on lobbying by industry-funded 'patient access' groups

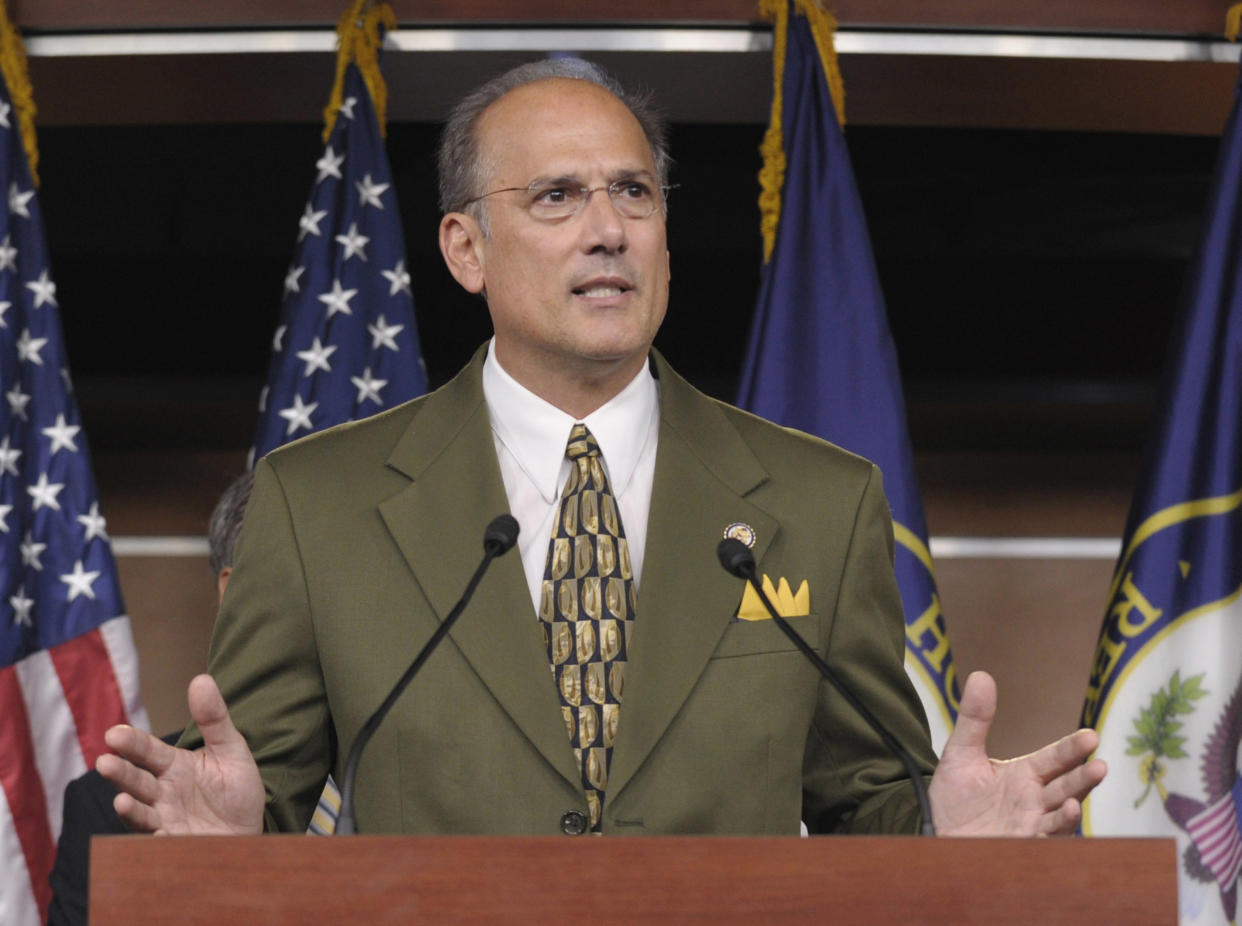

Rep. Tom Marino, President Trump’s pick for drug czar, unceremoniously withdrew his name from consideration after a public outcry over his ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including sponsoring a bill that weakened the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) ability to crack down on suspicious opioid sales. But the news stories that led him to quit also raised questions about how it could have passed through Congress with virtually no opposition and been signed into law by then President Barack Obama — an ally in the fight against opioid abuse.

The machinations of Washington are complex, but it’s hard to overstate the influence — often behind the scenes — of lobbyists. For years, the opioid industry has been funding nonprofit organizations that promote patient access to their drugs. These medical organizations pushed for Congress to approve Marino’s Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act, which serves the interests of major drug distributors and retailers.

On Jan. 26, 2015, a number of organizations nominally interested in ensuring legitimate access to pain medication wrote to Marino, Rep. Peter Welch, D-Vt., Rep. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., and Judy Chu, D-Calif., praising their fight for the now controversial legislation. They argued that the country needs need a balanced approach to the opioid abuse crisis that ensures access for pain patients while stopping drug abusers. Among the groups were the Alliance for Patient Access, which describes itself as “a national network of physicians dedicated to ensuring patient access to approved therapies and appropriate clinical care” and the American Academy of Pain Management (since renamed the Academy of Integrative Pain Management), which describes itself as an organization advancing “integrative pain care approaches” defined by the National Institute of Health.

As of June 2017, the Alliance for Patient Access’ list of associate members and financial supporters contains over two dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer and Purdue Pharma. The latter’s marketing practices have been blamed for fueling the opioid epidemic.

“Federal agencies, law enforcement, pharmaceutical industry participants and prescribers each play a role in working diligently to prevent drug abuse and diversion,” they wrote. “However, it is also imperative that legitimate patients are able to obtain their prescriptions without disruption.”

Andrew Kolodny, the co-director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University, said this argument — that legitimate pain medication patients should not pay the price for the fight against drug abuse — is how the opioid lobby has framed (and continues to frame) the issue of prescription abuse from the beginning.

“These pain organizations make the case for the opioid lobby. But if you scratch the surface, you’ll find that the pain organizations that signed the letter are receiving money from the opioid lobby,” Kolodny told Yahoo News.

Kolodny said the opioid lobby often uses “phony front groups” to support its efforts in blocking any reduction in prescribing — and uses them very effectively.

An explosive investigation by the Washington Post and “60 Minutes” released Sunday revealed that Marino had accepted large donations from the pharamceutical industry while pressing for the legislation that they favored.

The next day, Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill, the top-ranking Democrat on the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, announced that she would introduce legislation to repeal the law.

Adriane Fugh-Berman, a professor of pharmacology at Georgetown University Medical Center, said that the pharmaceutical industry creates or co-opts nonprofits to use as their mouthpieces. This is called “third-party strategy”: removing the drug industry’s fingerprints to make their marketing look like education or grassroots advocacy. She said by paying off groups, Big Pharma ensures their espousal of market-friendly opinions (such as endorsing new drugs to fight problems caused by old drugs) — and their silence on drug costs.

Fugh-Berman also directs PharmedOut, a research and education project at Georgetown that exposes the effect of drug marketing on prescribing. PharmedOut recently released a list of patient and consumer advocacy groups that do not receive payments from the pharmaceutical industry. They could only identify 10 health advocacy groups in the U.S. and six in Canada. Although Fugh-Berman acknowledges they may have missed a few (and plans to update accordingly), the number of truly independent voices is still tiny compared to the 7,685 patient advocacy groups in the U.S. None of the 19 pain organizations that signed the letter to Marino and others appears on the list.

“The voices of industry-funded groups drown out the voices of independent groups. That’s what is meant to happen,” Fugh-Berman told Yahoo News. “The industry-funded groups are undermining public health in this country.”

Fugh-Berman, who used to chair the National Women’s Health Network, cited the controversy surrounding the female-libido boosting pill flibanserin, sold under the trade name Addyi, as an example of how independent groups can differ drastically from industry-funded groups on these issues.

She said Sprout Pharmaceuticals gave money to women’s groups as part of a public relations campaign. The result was two conflicting pieces of advice to women, from groups that did, or did not, take the grants. The independent women’s groups said that viewing low libido as a disease was an invention of the pharmaceutical industry, and that the drug is actually dangerous, whereas the others called Addyi the biggest step forward in women’s health since the birth control pill.

“Unfortunately, the media represented this as a cat fight among the women’s groups,” Fugh-Berman said. “But if you actually separated it by funding, 100 percent of the groups that got money supported the drug and 100 percent that didn’t take money opposed the drug.”

On these issues, she wishes that more people would hear from the groups that can truly represent the interests of consumers or patients because they are not beholden to corporate funders.

“Those groups struggle for money. They struggle for survival,” she said.

Legitimate chronic pain organizations do exist. Kolodny noted that Pain Australia teamed up with a medical organization to keep codeine from being an over-the-counter drug.

“A legitimate pain organization would not be against efforts to address the opioid crisis or efforts to promote more cautious prescribing because opioids are lousy drugs for chronic pain,” Kolodny said.

Fugh-Berman said opioids are great medications for severe pain — such as the days after surgery or end-of-life care — but do not work well for chronic pain: they cause addiction, respiratory depression, cardiovascular disease, etc.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 91 Americans die from opioid overdose every day, and that more than a half-million died from drug overdose from 2000 to 2015.

The pharmaceutical and health products industry consistently ranks toward the top of lists of contributors to federal election campaigns. The Center for Responsive Politics reports that the industry donated $28,103,688 to congressional campaigns, with $23,215,767 going to incumbents during the 2016 election cycle. Congress has already received $6,965,956 for the 2018 elections.

Read more from Yahoo News: