‘Oppenheimer’ film draws debate over the absence of Japanese bombing victims

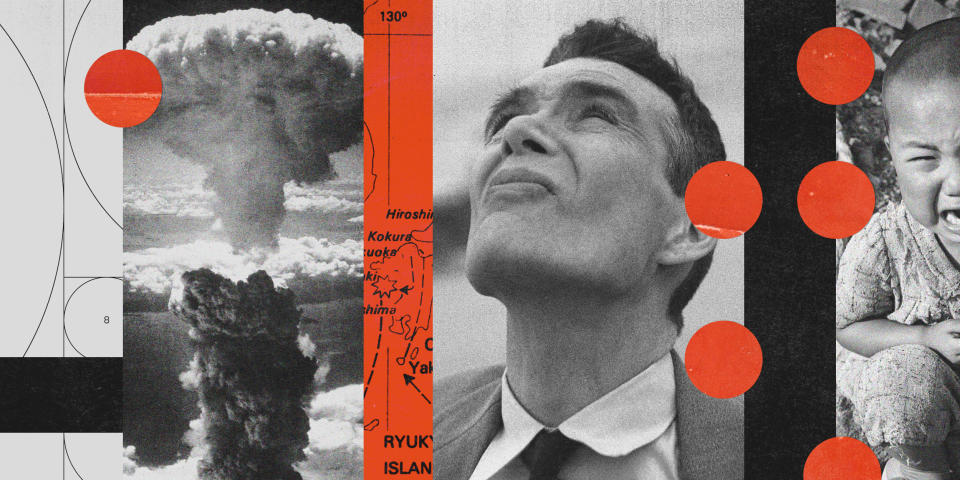

Blockbuster film “Oppenheimer,” which revolves around physicist Robert Oppenheimer and his development of the atomic bomb, has prompted discussion over the way the movie did not directly portray Japanese victims of the weapon.

Viewers are divided, with many criticizing the lack of Japanese representation as the erasure of the hundreds of thousands victims of Oppenheimer’s creation. Others, including director Christopher Nolan, argued that the film zeroes in on the scientist’s experience and perspective alone — one that is distinct and separate from the victims’.

Experts say that the issue of representation is more nuanced. They emphasized that while no one film has the responsibility to illustrate Japanese victims’ perspective, “Oppenheimer” does little to challenge the long history of glorifying the work of white men, and risks perpetuating the persistent, often reductive, portrayals of Japanese victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“I don’t think we should depend on Hollywood to tell our stories with the nuance and the depth and the care that they really deserve,” Nina Wallace, media and outreach manager at Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the stories of those of Japanese descent. “But it is true that these institutions that are in positions of power, positions of influence, put more value on stories of men like Oppenheimer, like Truman, than it does on the Asian and indigenous communities that suffered because of decisions that those men made.”

Based on the 2005 biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” the film was released Friday and follows the physicist’s ascent into his role as the director of the clandestine weapons lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico, as part of the Manhattan Project, the top-secret U.S. effort to make the first atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer’s work led to the deaths of more than 200,000 people by some estimates, as well as a generation of “hibakusha,” or survivors of the blast — many of whom continue to contend with the impacts of the bomb to this day. And the movie has largely been billed as a contemplation over the moral dilemmas facing the scientists.

However, Nolan doesn’t show the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the devastating aftermath in the cities. While there’s a scene that depicts American leaders discussing where to drop the bomb — with then-Secretary of State Henry Stimson depicted as arguing against Kyoto because of his honeymoon there — victims of the blasts never appear on screen. In another scene, Oppenheimer gives a speech and, while looking into the crowd, visualizes some of the predominantly white audience as the victims of his bomb.

Nolan said he did not illustrate the aftermath or the victims because he felt that “to depart from Oppenheimer’s experience would betray the terms of the storytelling.”

“He learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio — the same as the rest of the world,” Nolan said in a discussion with MSNBC’s Chuck Todd. “That, to me, was a shock … Everything is his experience, or my interpretation of his experience. Because as I keep reminding everyone, it’s not a documentary. It is an interpretation. That’s my job.”

Wallace said it’s not on “Oppenheimer” to show the Japanese perspective, nor should the movie be seen as a factual historical resource. Nolan, a white director, is likely not the appropriate artist to sensitively highlight the experiences of hibakusha, she said. But, experts added that doesn’t mean Nolan’s artistic decisions won’t have an impact on the American public’s view of Japanese civilians during World War II.

“Even within the realm of entertainment it’s still demoralizing and making, once again, unreal the experience of Asian people,” Brandon Shimoda, a Japanese American writer and curator of the Hiroshima Library.

Shimoda said that while the Japanese civilians and citizens are not included in the film, their absence makes a dangerous statement.

“(They) are the specter on the far side of the horizon, and therefore not entirely knowable,” Shimoda said. “What we’re meant to see when we look into the skeletal face of Oppenheimer is the distance between Oppenheimer and actual human beings.”

With its large-scale marketing and investment, the movie, which raked in $82.5 million domestically and $98 million internationally in its opening weekend, holds weight due to its massive audience, as well, Wallace said. But with a range of movies that focus on the American perspective, like 2001’s “Pearl Harbor,” there remains a further shifting of the victims’ experiences. Moreover, public education doesn’t help, providing little information or awareness around the continued health issues that victims face, she said.

“I understand how showrooms and Hollywood cannot be all-encompassing. … But I think it also points societally to the lack of nonwhite, non-U.S. initiatives or perspectives,” said Stan Shikuma, co-president of the Seattle Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. “That lack of more of a global perspective allows atrocities to continue to happen because we still dehumanize other people that we don’t know.”

Films about other perspectives, Shikuma said, often fall on the independent filmmaking community. But he emphasized that “it’s not a level playing field” and reach continues to be an issue.

“Other perspectives can be brought to film, but the funding is so uneven. Right now, millions and hundreds of millions of people will probably see this film,” he said.

To truly challenge the audience to contend with the horrors of the bombings, Shimoda said that narratives need to shift toward those who were impacted most.

“The experience and perspective of the hibakusha needs to be centered in whatever way possible,” he said. “There are people out there that are telling their stories in real time. The general white American relationship to that is to refuse those stories, and to turn instead to these dramatizations, which largely erase the people whose stories need to be told.”

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com