Order on family separation offers no relief for thousands already being held

By the time President Trump signed an executive order Wednesday afternoon halting the separation of families caught illegally entering the country along the southwest border — an act he and administration officials had previously insisted could only be done by Congress — at least 2,000 children had already been separated from their parents and placed in government-contracted facilities around the country.

The executive order appeared to pave the way to replace family separation with a policy of detaining entire families together, prompting a new flood of concerns from lawyers and immigrant rights advocates. But it made no mention of the families who’ve already been torn apart under the administration’s “zero tolerance” policy on border crossers, and it gave no indication there would be an effort to reunite them.

Hours after the order was signed, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, whose Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) has assumed custody of these children while their parents face criminal prosecutions for crossing the border without authorization, confirmed what many legal advocates had already surmised: Children who’d already been placed in ORR custody would remain there.

Before signing Wednesday’s executive order, Trump and others, including Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, had blamed a 1997 consent decree known as the Flores settlement for forcing them to separate families. Under Flores, which set legal standards for the detention and care of immigrant children apprehended at the border, courts have ruled that minors cannot be held in immigration detention for more than 20 days even if they’re with their parents, as the Obama administration learned when it was ordered to stop detaining families amid a surge of children and parents crossing the southwest border in 2015.

No court, however, has ever interpreted this to mean that parents and children must be separated after 20 days. Yet the Trump administration, determined to carry out the hardline policy of criminally prosecuting every adult caught illegally crossing the southwest border, refused to adhere to the previous administration’s common practice of holding parents who crossed with their children for no more than 20 days, then releasing them with a notice to appear in court. Instead, adults would be detained and processed for criminal proceedings, while minors would be turned over to the Department of Health and Human Services and placed in ORR’s program for “unaccompanied alien children.”

“What’s already been done is atrocious, and there’s no plan to fix it,” said Nithya Nathan-Pineau, an attorney and senior program director for the Detained Immigrant Children’s Program run by the Capital Area Immigrants’ Rights Coalition (CAIR). Given the distance and lack of communication between parents and kids who are detained by two different government agencies, she predicted that these families will be “separated for the foreseeable future.”

Trump’s order vowed to continue the zero tolerance policy for all unlawful border crossers, but on Thursday the Associated Press reported that federal prosecutors in McAllen, Texas, had inexplicably dropped misdemeanor charges against 17 adults who were expected to be sentenced for unlawfully entering the country. All of them had been separated from their children after crossing the border, but whether they would be released and reunited with their kids or moved to ICE detention was not immediately clear.

The Washington Post also reported Thursday that, according to an unnamed senior official, the administration is “suspending prosecutions of adults who are members of family units until ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) can accelerate resource capability to allow us to maintain custody.” A spokesperson for the Justice Department quickly disputed the Post’s story as inaccurate, tweeting that “There has been no change to the Department’s zero tolerance policy to prosecute adults who cross our border illegally instead of claiming asylum at any port of entry at the border.”

The CAIR Coalition provides legal services to immigrant kids housed in ORR-funded facilities throughout Maryland and Virginia. For the most part, those are teenagers who crossed the border on their own, often fleeing violence in places like El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, in hopes of seeking asylum in the U.S. But in recent months, the six shelter-level facilities Nathan-Pineau works with have also been receiving a steady stream of kids who’d made the journey to the border with their parents only to be separated and reclassified as “unaccompanied” upon arrival.

Nathan-Pineau said ORR actually started sending these “separated children” to Maryland and Virginia before April 19, when the zero tolerance policy was officially implemented, but the numbers started to increase significantly after the first week of May, when Attorney General Jeff Sessions vowed that his Justice Department would prosecute “100 percent” of the people who illegally cross the southwest border. Since then, she said, those Virginia and Maryland facilities, which comprise a total of 250 beds, have been receiving consistently between 8 and 15 separated kids each week, a mix of boys and girls, ranging in age from 4 or 5 to teenagers.

While the majority of these facilities are designed to accommodate teenagers, Nathan-Pineau said that two of them have what ORR calls “tender age programs,” which are meant to serve younger children, though she’s also seen “younger-than-normal kids” at facilities without these programs.

“I don’t think they have enough placements for all the kids under 12 that have been separated,” she said.

Despite the Trump administration’s efforts to conflate the children who’ve been separated from their parents with the larger population of teenagers who actually did arrive by themselves, to the case managers and legal service providers who are used to working with the latter group, the difference between the two is stark.

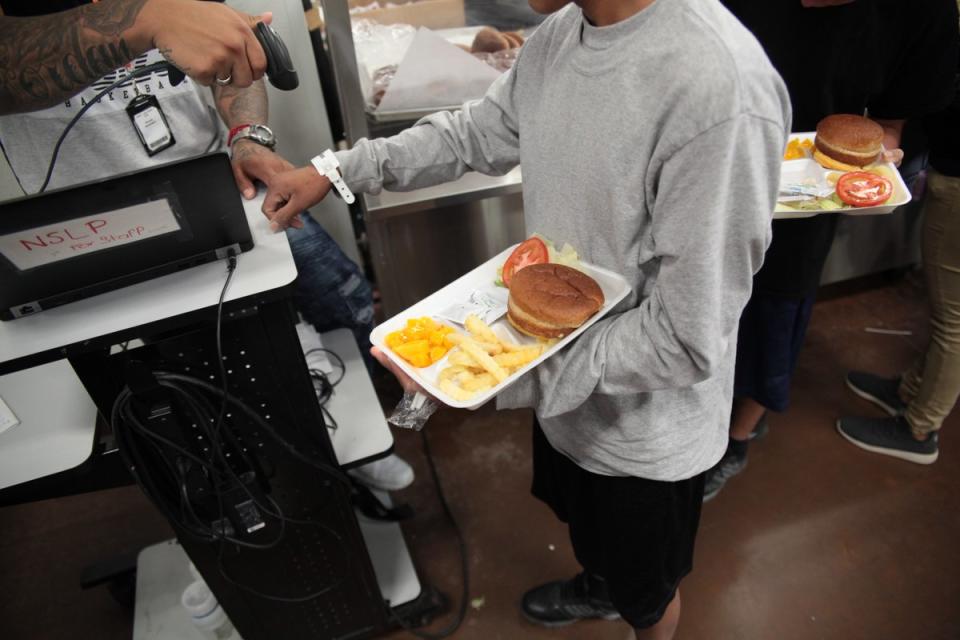

For many teenagers who fled violence and made the long, often traumatic journey to the U.S. on their own, the experience of being placed in ORR custody, where they can have regular meals and sleep on a bed with a roof over their head, is something of a temporary relief. But for those who’ve been separated from their parents, the transfer to another facility — in many cases by plane — only seems to compound the trauma they’ve experienced since arriving in this country.

“The [separated] kids are inconsolable,” said Nathan-Pineau, adding she’s observed these children “crying all the time” and exhibiting “behavioral issues.”

“They can’t even have a conversation,” she said. “This isn’t typical. It’s an extra layer of trauma that these kids are going through.”

For case managers at established ORR facilities, whose job is to try to place unaccompanied immigrant kids with parents, close relatives, or other suitable sponsors within the United States, one of the biggest hurdles to helping this new category of kids is tracking down their parents.

Typically, teens who cross the border unaccompanied come prepared with the name and contact information of a parent or relative who has already agreed to take them in and can help provide advocates with some of the information and records needed to file asylum claims. But that’s hardly the case with kids who made the journey north with their parents, and for some reason case managers are encountering a lack of communication between ORR and the Department of Homeland Security, which ostensibly could easily provide information about the parents’ whereabouts.

“The consistent question we keep getting from kids is, ‘Can you help me find my parents? Can you help me make a call to my parents?’” said Nathan-Pineau. “It’s a really heartbreaking situation, even for our staff who are used to working with traumatized kids who are recently arrived. This is something that’s at a different level.”

Nathan-Pineau worries that these hurdles will make it even harder to get the separated children released from ORR, a process that has already slowed significantly under the Trump administration.

“The practical barriers to getting these parents and kids back together given the lack of coordination are just mind-boggling,” she said, predicting that, ultimately, “More kids will be spending longer periods of time in short-term facilities, not designed for kids to live there long-term.”

The six shelter-level facilities currently housing some of these children in Maryland and Virginia are part of a network of around 100 such facilities operated through contracts with ORR in 17 states. By late May, with Sessions’s ‘zero tolerance’ border crackdown creating a sudden influx of “unaccompanied” minors, these facilities had reached 95 percent capacity.

According to Kenneth Wolfe, a spokesperson for HHS’s Association for Children and Families, “There are currently 11,799 minors in our unaccompanied alien children program.” HHS has declined to specify what portion of that population was actually unaccompanied when they crossed the border, but last week DHS officials told reporters that 1,995 minors had been taken from their parents or “”alleged adult guardians” after unlawfully crossing the southwest border between April 19 and the end of May. On Tuesday, NPR reported that border officials had separated 2,342 migrant children from their parents since early May.

In response to this government-created surge, the government has begun housing immigrant children in larger, emergency accommodations like the Homestead Temporary Shelter for Unaccompanied Children, which was first opened during the Obama administration near an Air Force Reserve base south of Miami, and a newly commissioned tent shelter in Tornillo, Texas.

Elected officials have been able to tour the temporary Tornillo facility, which HHS spokesperson Wolfe said has a current capacity of 360 teenagers, despite reports that it has the potential to accommodate 4,000. Staff at Homestead, where Wolfe said 1,204 teens are currently being housed, have been less welcoming.

This week, Sen. Bill Nelson and Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz were denied access to the Homestead facility, along with state Rep. Kionne McGhee, raising suspicions about the conditions inside the facility.

One ORR service provider who was recently allowed to tour the facility described “an overwhelming number of children” housed in narrow structures packed so tightly with bunk beds that the kids “can barely stand between bunk beds without being cramped.”

“These are not conditions that children should be living in,” this person said, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

The Associated Press reported this week that ORR is housing children under the age of 13, including infants and toddlers, in three newly repurposed “tender age” shelters in southern Texas and was planning to open another, larger facility in Houston to accommodate hundreds of these younger immigrant kids.

Some advocates worry about the potential for abuse and neglect at some of these temporary shelters. They note that standards are often relaxed in the rush to set up and staff emergency facilities and that reports of abuse against children in ORR custody have surfaced following previous influxes, including at Homestead.

“Any time you are doing things quickly, [you’re] much more likely to be sloppy. Things fall through the cracks,” said Diane Eikenberry, associate director of policy for the National Immigrant Justice Center. She added that such hurried hiring could result not just in potential predators on staff, but also “people who may not have the experience or the capacity to treat children in a way they should be treated.”

“This job of being frontline care workers for these kids has always been a difficult job — it’s always emotionally taxing for anyone,” she said. “Then you add this additional stress of extremely traumatized children who are manifesting stress in ways that are really hard to manage for anyone. Combine that with rushed implementation and fewer resources for staff and you have this terrible recipe for disaster.”

Eikenberry predicted that, under these circumstances, it’s “much more likely that these kids are going to suffer mistreatment despite the best intentions of the agency.”

HHS’s Wolfe did not respond to questions about how the agency is ensuring that members of the child care staff at emergency facilities are being properly vetted while quickly working to accommodate the large numbers of minors in ORR’s care.

But Eikenberry argued that even the most established, well-run facilities are hardly equipped to handle the trauma experienced by children who’ve been taken from their parents at the border.

“These kids are traumatized, suffering, permanently harmed because of separations,” she said. “Even extremely well-trained staff can’t fix that.”

Read more from Yahoo News: