Parents think their kids are doing well in school. More often than not, they're wrong.

LaShanta Mire’s daughter was, at least on paper, thriving at her public school in Fort Worth, Texas. Her grades were good. The then-second grader was ostensibly learning to read and was performing at the level expected of kids her age.

But the child’s assessments told a different story: She did not yet know how to read. She was missing out on crucial content. She wasn’t performing at grade level.

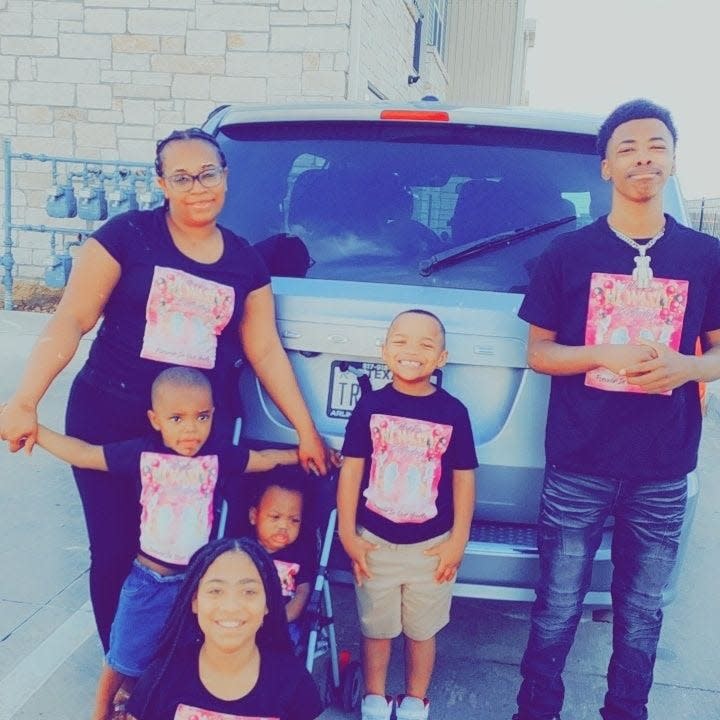

Mire, like possibly millions of parents across the U.S., received flawed information about her daughter and her two other school-age children. After realizing there was a mismatch between her perceptions and the realities of how her child was faring academically, the single mother of five took it upon herself to find a parents group to help her navigate school bureaucracies, engage with educators and seek information such as test scores. As soon as she got the information she needed, Mire transferred the three oldest children to new schools last fall.

Now they’re getting grades that offer a more accurate – if sometimes disappointing – picture of their achievement. “I felt like I was failing my child because the school was failing her,” Mire said of her now-9-year-old daughter. Her new school, she said, “doesn’t just give you (good) grades. … You have to earn them.”

Mire's daughter is among a generation of children who missed lots of class time and lost significant academic ground during the pandemic. Four years after the onset of COVID-19, schools are still struggling to catch kids up. They’re also struggling to get young people to show up. Chronic absenteeism – when students miss at least 10% of the school year – remains rampant and in some cases has gotten worse.

Yet schools aren’t adequately communicating these challenges to families and often, in fact, mistakenly communicate that all is well. Research suggests parents are getting limited, if not inaccurate, messages about their kids’ performance.

New survey findings, shared exclusively with USA TODAY, underscore the problem: Nearly half of parents say they want better communication from their kids’ schools – especially about attendance.

One-third of parents do not feel well informed about their children’s academic progress and school success, according to the survey from a K-12 communication and data analytics platform called SchoolStatus. The survey among roughly 1,050 parents and caregivers of children 6 to 18 complements separate polls that asked parents about their kids’ performance since the pandemic. The latest findings illustrate the stubborn disconnect between families and schools when experts say it’s crucial they be in sync.

“It’s crazy that schools have all this data and parents don’t,” said Russ Davis, founder of SchoolStatus. “Parents assume no news is good news” – but that’s seldom the case.

Distracted students, stressed teachers: What an American school day looks like post-COVID

Amid widespread grade inflation, parents demand better information

Nearly half (45%) of the respondents in the SchoolStatus survey said communication wasn’t frequent enough, and a similar percentage said they didn’t get messages about the importance of attendance until after their kids missed school.

The findings about a gaping disconnect are more glaring given growing evidence that chronic absenteeism can take an immense toll on learning for all students and that proactive communication with parents about their kids’ attendance patterns and the benefits of class time can markedly reduce absences.

Most parents said they got some updates about their children’s academic progress, but fewer than a quarter said they received information and resources to support learning at home.

“There’s a real erosion of connection between school and home,” said Kara Stern, the director of education and engagement at SchoolStatus. The survey findings, she said, “can be summed up into one sentence: Parents want to know.” And they want to know not just what their kids’ grades are but also how those students are progressing and where they’re lagging – and how to take action when needed.

Other research also shows a gap between students’ marks on their report cards and those on standardized assessments.

Grade inflation is nothing new: Schools have long tended to overstate how well kids are faring, said Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University who studies education. But it has become an especially popular tactic in the COVID-19 era and its aftermath as schools work hard “to say, ‘We’re back up to where we were before,’” he said.

Research conducted by Gallup in partnership with Learning Heroes, a nonprofit that supports family engagement, has shown that nearly 9 in 10 parents believe their children are performing at or above grade level.

But other measures indicate the rate of students achieving what’s expected for their age group is far lower. Few parents in the Gallup and Learning Heroes survey were aware their children were behind. More than a third of the small percentage who said their kids were below grade level believed their students received mostly Bs or higher. Nearly 2 in 3 parents cited report cards as an important source of information about whether their kids were at grade level.

Parents are desperate for accurate information, no matter how demoralizing. As Mire, the mother who relocated her children, put it, “I just need my babies to do better.”

‘After the fact is too late’

Thomas Kane, a Harvard University scholar researching COVID-19 learning loss, said accurate information also needs to arrive swiftly. Parents should be able to act on that information – by signing their children up for summer school or intensive tutoring, for example – before the resources are no longer available.

Shareeda Jones, another single mother of five, had an experience similar to Mire's. She also wasn’t informed until recently that her fifth grade daughter was reading at a second grade level. The Washington, D.C., public schooler is doing daily phonics lessons and trying to catch up, but Jones worries she has already lost precious time. She now faces the prospect of being held back.

Parents such as Jones – a product of Washington's public schools who felt she was pigeonholed into special education – care deeply about ensuring their children are spared any of the educational neglect they experienced. “A lot of us just don’t understand how to care, don’t know where to look to care,” Jones said. But she said getting the information she needed to intervene after the fact was too late.

Jones managed to find a summer program for her daughter last year but realized a few weeks in that she wasn’t learning much. She has pleaded with the school: “Help me help you all to help my child.”

Kane’s research on pandemic learning has shown that kids in the past school year made up about one-third of their pandemic-era math losses and one-quarter of their reading losses. That, in some ways, was “a remarkable achievement” given that it required learning at a faster pace than normal. But even if students have continued that pace this school year, they still won’t have recovered all their learning when summer comes. The unprecedented infusion of COVID-19 relief funding schools received – which supported massive interventions including summer school and tutoring – expires this fall.

“We’ve got to get as many students as possible signed up for summer learning, and that means making sure parents are aware their kids are behind grade level,” Kane said. “Somehow, somewhere, the message is not getting through.”

Who’s to blame for the communication gap?

Few, if any, teachers intend to set up students for failure or mislead families.

The communication mismatch partly stems from the public’s fatigue over pandemic learning losses. Even when they hear about the dire circumstances schools are facing since COVID-19, many parents are inclined to believe the narrative doesn’t apply to their kids. “They see stories about how achievement has gone down and (think), ‘It must be those other guys,’” Hanushek said. Separate research has shown parents often give the nation’s K-12 system mediocre or bad grades but assign high marks to their children’s schools.

Attending school was hard during COVID Why aren’t kids (or teachers) returning to class?

Beyond that, experts say, systemic challenges are at play. Educators are expected to track, compile and analyze overwhelming amounts of data, often using a patchwork of systems.

“This is not about a failure of teachers,” said SchoolStatus’s Stern. “We’re talking about a failure of systems, about teachers being so overburdened and so overwhelmed and systems being so inefficient that nobody can keep up.”

The SchoolStatus platform, which compiles all kinds of data into one place and sends it in customized messages to parents, is one solution to those systemic failures, she and founder Davis said.

Either way, Hanushek says, families need a wake-up call – and facing this urgent gap would benefit the nation’s economy. One of his studies found that recent achievement declines among students in the COVID-19 generation could result in them earning 6% less in their lifetime than other Americans.

“The schools are saying, ‘Well, we’re working to get back to where we were, but things are coming along,’” Hanushek said. Such a sanguine approach, he said, often means students don’t get the opportunity to catch up to where they should be. And if that doesn’t happen, “They’re going to be saddled with these losses forever."

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or [email protected]. Follow her on X at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Report cards don't reflect reality: Parents seeking more from schools