In Photos: Remembering the Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster 20 Years Later

The 28th flight of NASA’s Space Shuttle Columbia ended in disaster on February 1, 2003, while it was 27 miles above the state of Texas, marking the second catastrophic mission of NASA’s shuttle program. Twenty years later, the tragic event serves as an important reminder of the dangers posed by space exploration—and why astronaut safety should always be a priority.

A falling chunk of insulating foam weighing no more than 1.67 pounds—that’s all it took to take down the 179,000-pound Space Shuttle Columbia. The debris formed a gash in the orbiter’s left wing, compromising the Shuttle’s thermal protection system. The orbiter disintegrated during reentry on February 1, 2003, resulting in the deaths of all seven crew members on board.

Read more

These Winning Close-Up Photos Show Life That's Often Overlooked

Remembering Enterprise: The Test Shuttle That Never Flew to Space

An ensuing investigation uncovered serious faults with NASA’s safety culture, but the Shuttle’s exorbitant cost and poor safety performance signaled the beginning of the end for the program, which ended just eight years later.

The STS-107 crew

The STS-107 crew (from left to right): David Brown, Rick Husband, Laurel Clark, Kalpana Chawla, Michael Anderson, William “Willie” McCool, and Ilan Ramon, the latter from the Israeli Space Agency. STS-107 was the first Shuttle mission of 2003 and Columbia’s 28th overall. Columbia, the oldest Shuttle in the fleet at the time, was also the first Shuttle to reach space, having done so on April 12, 1981. The STS-107 mission launched from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January, 16, 2003.

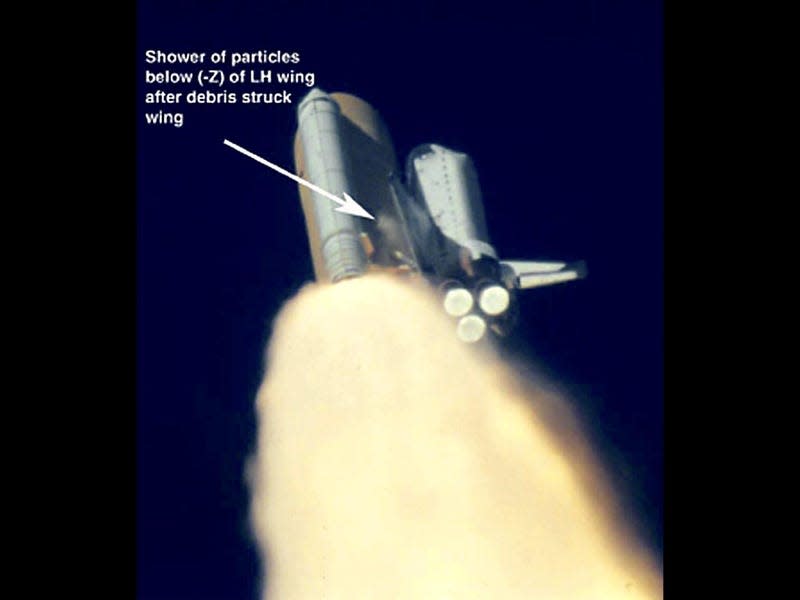

Debris strike

During launch, a piece of insulating foam came loose from the Shuttle’s External Tank (ET) and struck the underside of Columbia’s left wing, creating a shower of particles. The incident happened roughly 82 seconds into the flight, but mission engineers only came to be aware of the strike a few days later, while performing a routine analysis of launch films.

Husband and McCool were told about the debris strike on January 23, the eighth day of the mission, but were told that there was “absolutely no concern for reentry” as foam strikes had been observed on previous missions and to no ill effect. Regrettably, this assessment proved to be catastrophically wrong, as the resulting damage to the wing rendered it unable to withstand the extreme temperatures endured during atmospheric re-entry.

Working in space

The STS-107 crew posed for this amazing shot during the mission. The photo was on a roll of unprocessed film that was later recovered during searches of fallen Columbia debris. Husband, seen here holding the remote camera control, informed the crew about the debris strike. Back on Earth, engineers continued to evaluate the situation and asked for high-resolution imaging of the affected area to better evaluate the state of the Shuttle. Mission managers turned down the request. The ensuing Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) was critical of NASA’s organizational and safety culture, “finding similar faults that led to the 1986 Challenger accident,” according to the agency.

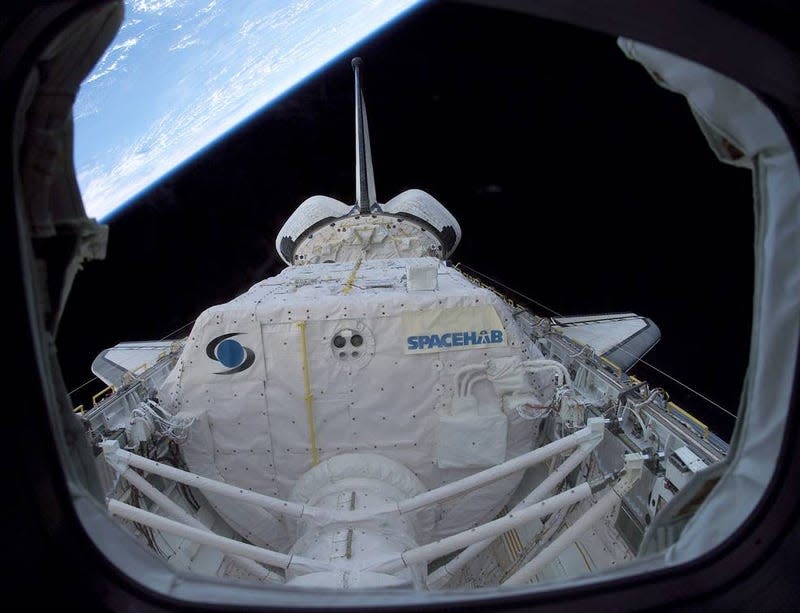

The Spacehab payload

While in space, the seven-member crew performed many of its 80 planned science experiments within the Spacehab Double Research Module located in the Shuttle’s payload bay.

At work in space

This photo shows mission specialist Kalpana Chawla and Commander Rick Husband working inside the Spacehab research module. Many of the experiments done during the STS-107 mission were applicable to future studies aboard the International Space Station, which made its debut in 1998.

Inside Spacehab

Mission specialist Laurel Clark—donning purple gloves—posed for this photo while running an experiment inside Spacehab. The Shuttle program, initiated in 1972 during the Nixon administration, was pitched as a reusable “space truck” for transporting crew, cargo, and satellites to low Earth orbit, and as a platform for conducting microgravity experiments.

At the controls

Pilot William McCool inside Columbia’s aft flight deck.

Final moments

This video still shows members of the STS-107 crew before the accident, as the Shuttle began its atmospheric reentry. During the final exchange of words, a mission controller said, “To Columbia, here is Houston...we did not copy your last message.” A few moments passed by before Husband responded with, “Roger...,” followed by an indiscernible word that got cut off. The dialogue happened at 8:59 a.m., with the Shuttle disappearing from radar screens less than a minute later.

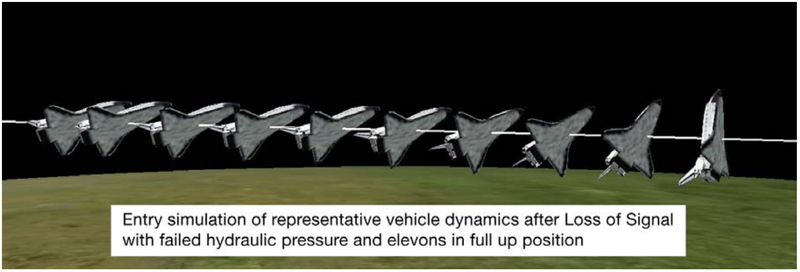

Uncontrolled ballistic trajectory

The CAIB report concluded that during re-entry, a breach in the Shuttle’s thermal protection system “allowed superheated air,” at temperatures reaching 2,760 degrees Celsius, to “penetrate through the leading edge insulation and progressively melt the aluminum structure of the left wing, resulting in a weakening of the structure until increasing aerodynamic forces caused loss of control, failure of the wing, and breakup of the orbiter.”

The Spacecraft Crew Survival Integration Investigation Team (SCSIIT) concluded that the loss of hydraulics caused Columbia to pitch upwards, as the Shuttle transitioned from “a controlled gliding trajectory into an uncontrolled ballistic trajectory,” the SCSIIT team wrote in its report.

Shedding debris

This is a profile view of the intact Shuttle prior to its destruction, as seen from Kirkland Air Force Base in New Mexico. The image shows a debris trail emanating from Columbia’s left wing.

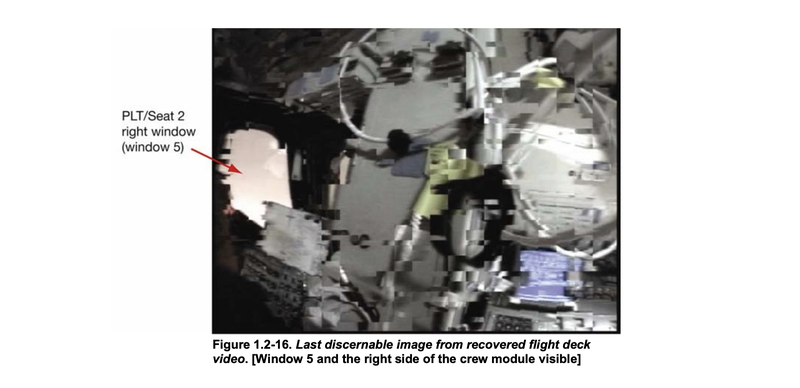

Final frame

Video taken from inside the cabin during re-entry helped the investigators to piece together a timeline of events. The frame above is the last discernible video image from the Columbia mission. The Shuttle disintegrated over the course of 24 seconds, with depressurization, along with the astronauts’ “loss of consciousness and cessation of respiration,” happening shortly after 9:00 a.m. ET, according to the SCSIIT report. The crew module was 26.5 miles (42.7 km) above the surface at the moment of its destruction.

Debris over Texas

Debris from the disintegrated 82-metric-ton Shuttle appeared above Texas, including this photo taken from Dallas. Remnants from the orbiter fell onto parts of Texas and Louisiana.

Shattered Shuttle

Another view of the Shuttle after it broke up, this one taken from Tyler, Texas. The astronauts, exposed to virtually no oxygen, depressurization, low atmospheric pressure, and hot gases, had no chance of survival. Columbia broke up over eastern Texas, 16 minutes before its scheduled landing in Florida.

Control room map

A video still of the mission control room monitor at the Johnson Space Center showed the location of Columbia when NASA lots contact with the incoming orbiter.

Fallen debris

This is a main engine powerhead from Columbia, which was recovered in Fort Polk, Louisiana.

Deadly foam

Space Shuttle program manager Ron Dittemore held a piece of insulating foam at press briefing on Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, held on February 5, 2003 at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Its ensuing report, investigators said NASA “had become complacent to the loss of foam from the [external tank], since none had led to significant issues other than postflight maintenance,” the agency said.

The reconstruction team at work

Recovered fragments belonging to Columbia were brought to Kennedy Space Center’s Reusable Launch Vehicle hanger for the ensuing investigation. In this photo, elements from the Shuttle’s left wing can be seen lying on a table in their relative position. Burn marks, deposits of molten material, missing tiles, and other signs of damage helped the reconstruction team determine how the left wing failed during reentry.

Columbia window

A recovered Columbia window lying exterior-side up inside the reconstruction hangar, March 3, 2003.

Tragic puzzle

Identified main fuselage debris were placed on a grid system inside the Florida hangar. Experiments performed during the course of the 16-day mission were not completely lost, with scientists recovering between 50% to 90% of the results, mostly due to the downlinking of data prior to the disaster. That said, an experiment containing the microscopic worms C. elegans was recovered amid the fallen debris, having survived the crash.

Foam impact tests

The CAIB conducted foam impact tests on replicas of Columbia’s left wing at the Southwest Research Institute. These tests largely replicated the damage incurred by the Shuttle during launch, forming a 16-inch-wide gash on a wing replica.

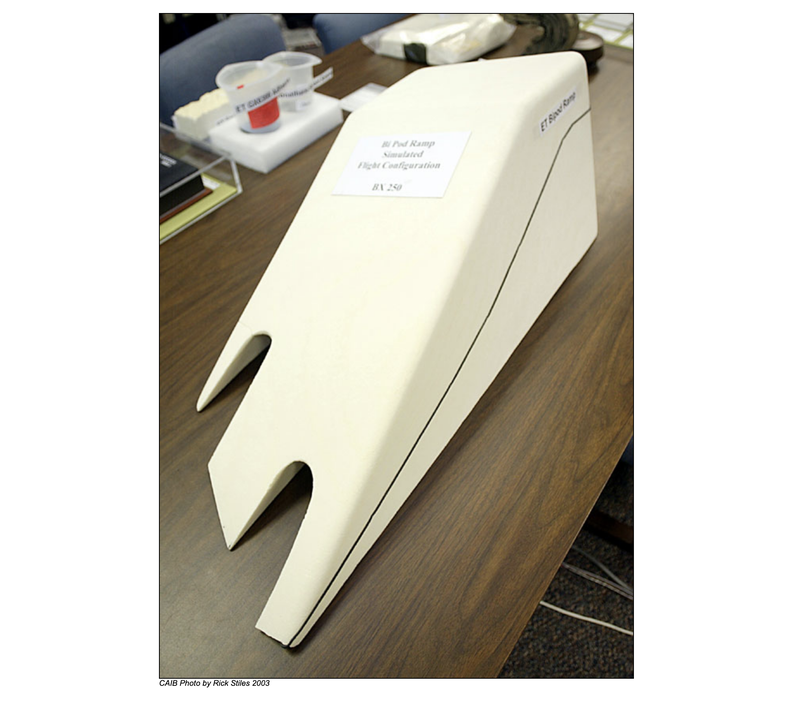

The culprit

Above is a foam model from the Shuttle’s left bipod ramp. The area above the black line is presumed to approximate the area and mass of the foam that struck Columbia’s left wing. Incredibly, the chunk weighed no more than 1.67 pounds.

As the investigators learned, damage from falling debris was a fixture of every Shuttle flight. What’s more, STS-107 marked the seventh occurrence in which falling foam was recorded. NASA engineers didn’t believe it was possible for such a low-density object to cause so much damage, but at speeds reaching more than 500 miles per hour (804 km/hr), the tumbling foam, packed with extra rotational energy, exacted considerable damage to the wing’s reinforced carbon panel.

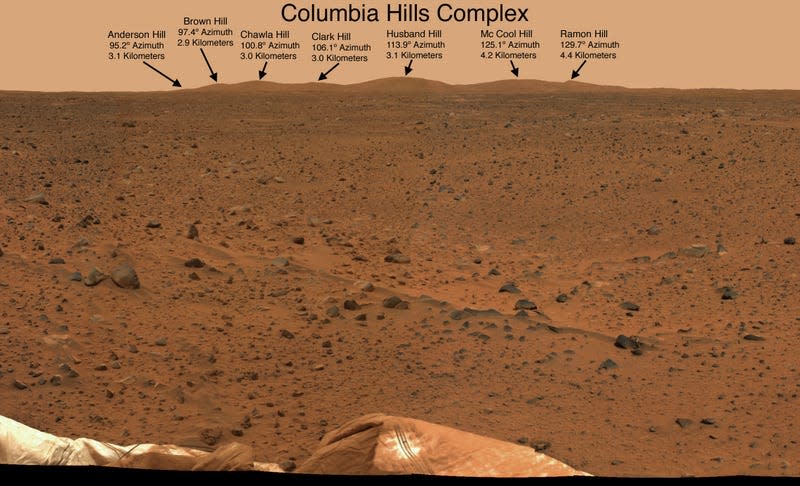

Columbia Hills on Mars

On February 2, 2004, NASA named individual peaks inside Mars’s Gusev crater in honor of the fallen astronauts. The peaks were spotted by the agency’s Spirit rover and are located around 1.9 miles (3 km) from the landing site.

NASA’s Day of Remembrance

This photo shows people attending a NASA Day of Remembrance ceremony on Thursday, January 26, 2023, in the Astronaut Tree Grove at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Evelyn Husband Thompson was speaking about her late husband, Rick Husband, at the time. Fallen astronauts from Apollo 1 and the Space Shuttle Challenger were also honored at the ceremony.

In total, 14 astronauts died during the 135 Space Transportation System missions from 1981 to 2011—a failure rate that left a mixed legacy for the now-retired Shuttle program.

More: The Space Shuttle Was a Beautiful—but Terrible—Idea

More from Gizmodo

Sign up for Gizmodo's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.