Profit and despair inside California's largest immigrant detention camp

ADELANTO, Calif. — On the outskirts of the high desert town of Adelanto sits a welcome sign with the words “The City With Unlimited Possibilities.” For residents of an immigration detention center located here, the sign must feel like a cruel hoax.

I visited Adelanto in mid-November, on a bright sunny day, as part of an investigation into immigration detention for the nonprofit Project on Government Oversight. One of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s largest detention camps is located in the city. More than 1,700 detainees on an average day wait to have their immigration cases heard — the length of their time in detention varies from days to months or even years. Some will be allowed to stay, some will be deported. Over the years, a few haven’t made it out alive from the facility, which is run by Florida-based GEO Group, one of the country’s biggest private prison operators.

Founded in 1915, the city of Adelanto sits amid the Inland Empire, a term local historians say developers coined to sell this region as the new hub of Southern California. It didn’t work out that way. The Inland Empire evolved into an agricultural center, but by the 1950s, most farmers had been pushed out by industrial and military development. Once factories and military bases started closing in the 1970s, the region entered a period of decline. It underwent a superficial revival in the 1990s when high housing costs pushed people out of Los Angeles and bankers and assorted hucksters lured them to the desert with cheap homes and easy credit.

Then the real-estate bubble popped in the 2000s. Residents found themselves stuck in the middle of nowhere in homes worth far less than they had paid for them.

Adelanto means “progress” in Spanish, but the town is a dead flat wasteland of trailer parks, empty lots and desert scrub. The work situation is as dreary as the parched landscape. George Air Force Base closed down about 26 years ago. Outside of the logistics industry — moving cargo into and from warehouses — waste management is the major industry. Some 34,000 live here, with about 39 percent in poverty. Median annual household income is $34,000. Adelanto ranked 254th, dead last, in a recent survey of the state’s best cities to raise a family.

The conditions that make the town the “worst place” to raise a family, according to that survey, are what makes it an ideal spot for the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, the largest immigration detention camp in California. There are two other incarceration facilities within the city limits and a massive federal penitentiary seven miles down the road in Victorville, a large federal prison where many immigrant detainees were held earlier this year before being transferred to Adelanto.

I made the 90-minute drive to Adelanto from Ontario with Jennaya Dunlap, the nonprofit Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice’s deportation defense coordinator. Dunlap and other advocates told me that most detainee complaints at Adelanto’s detention center are about medical care. “You have to wait so long to be seen you’ll get better or die first,” she said. “One young man I know had diabetes and he needed two types of insulin, but they only gave him one. He got taken to the hospital in a coma twice.”

During our drive to Adelanto, Dunlap’s phone rang constantly. She said she was hearing more reports of ICE violating detainee rights. She told me about one man who was parked in front of his house and wouldn’t get out of his car when ICE showed up to pick him up. ICE officers, she says, slashed his tires, dragged him out of his vehicle and pepper sprayed him. “He had an outstanding arrest and deportation order, but that was a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment,” she said.

Dunlap said that under President Barack Obama, ICE usually targeted people with serious offenses but now it was frequently picking up people who had old nonviolent convictions, like DUIs. Under President Trump, she said, all prior convictions, no matter how old, are grounds for detention.

She’s helping one man who took away his teenage son’s iPhone when his school called and said he’d been truant. To get even with his parents, the boy told the police his father had beaten him up. After his father was arrested, the son acknowledged that it was a false complaint and the district attorney dropped charges. But ICE picked the father up on his way to work two days later based on the arrest. “The father had no priors, but any excuse will do,” Dunlap said. “This is typical of the logic we’re seeing.”

Just as she finished telling the story, the man’s son called to say his father had been released on a $5,000 bond. She explained that the family needed to go to the downtown Los Angeles federal building, fill out paperwork at the ICE office and buy five $1,000 money orders. With luck, his father would be freed that night, but he might still soon face deportation.

As the government has sought over the past two years to expand the number of people subject to deportation, Adelanto has become a key way station in the process. In many ways, it is emblematic of the worst abuses critics say result from these policies: inadequate medical care, labor exploitation and putting profit above people. And much of this is the result of an immigration process singularly focused on deportation.

“The system has become a pipeline for removal,” Dunlap said. “If you’re Mexican and you have a prior deportation order, you’ll be in Tijuana by nightfall. If you’re Central American, you’ll get taken to Adelanto or another detention center. It may take a few days until they’ve rounded up enough people to fill a plane, but you’ll be gone soon.”

*****

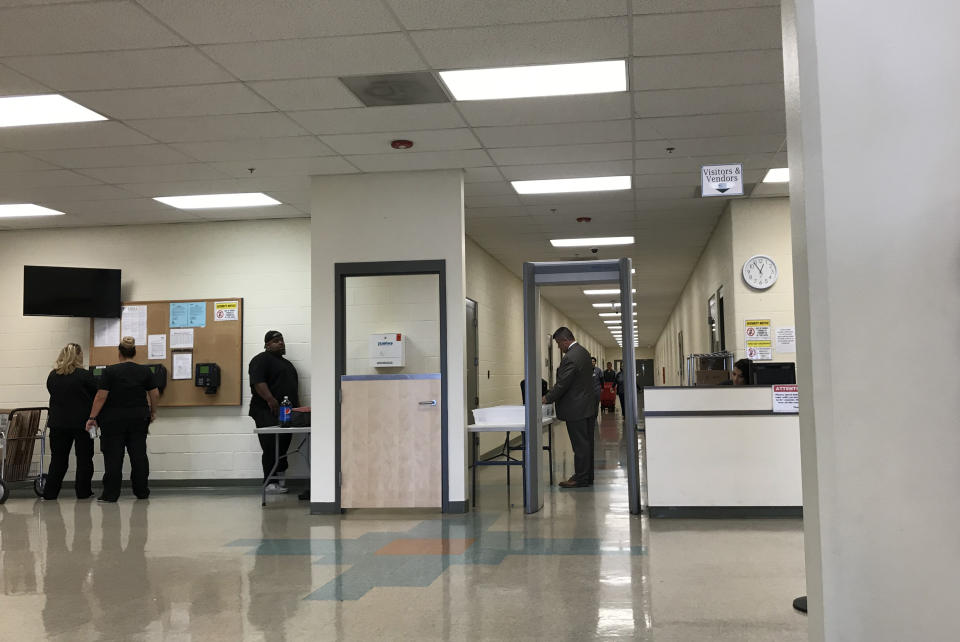

Three flags fly outside the Adelanto ICE Processing Center: The U.S. flag, the California state flag and the green, blue and white corporate banner of GEO Group, which operates the facility under a contract whose terms are not publicly disclosed. I visited the facility with Dunlap’s group, which was there to visit detainees.

Dunlap brought a list of about a dozen Adelanto detainees she advises or who have recently asked for the Inland Coalition’s help: a Brazilian soldier who recently fled his home country whom she had only talked to by phone; a Guatemalan man who had been shot twice and whose three brothers had been killed in gang violence; an Indian detainee who had recently arrived in the U.S. and whom she as yet had little information about; and three women, two from Central America and a Romany from Romania who was asking for asylum after being kidnapped and beaten there.

We checked in with a guard at the front desk and took seats in a large waiting room. It was easy to spot the lawyers wearing business suits, carrying brown accordion folders bulging with files. There were only about 10 visitors besides me and Dunlap, who prepares tax returns for immigrants in addition to her full-time job. Four were Latino men from Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Riverside who visit as part of their church work. The rest were family members of detainees. “A lot don’t come because it’s not easy to get out here,” Dunlap explained. “Many of them are afraid they’ll end up detained or deported, even if they are totally legal.”

We passed doors for a GEO training room and the Adelanto Immigration Court. Having the court at the facility means ICE doesn’t have to transfer detainees to an outside location, making it easier for the government to rapidly process cases.

At the end of the short hallway was the large visitors’ room. Alex Armando Villalobos Veliz of Honduras, 27, was waiting at a table to see me. He and his 18-year-old brother, Wilson, turned themselves in at the border, requested asylum and have been detained at Adelanto for three months. They say they fled threats of violence by a narco gang in their hometown of San Pedro Sula, reportedly one of the most violent cities on the planet. “The gang killed our cousin and told us we would be killed if we didn’t work selling drugs,” Alex said.

They may have a steep hill to climb to win asylum, even if the government accepts their story, because former Attorney General Jeff Sessions changed the standards that had allowed victims of drug cartel threats — as well as domestic violence — to win asylum. His argument was that those threats come from private individuals, not governments. (Earlier this week, a federal court struck down the Trump administration’s proposals to change the standards for immigrants fleeing gang and domestic violence.)

Alex Villalobos and I sat across from each other on blue plastic chairs at a small white table. Alex had on a blue uniform like four of the six detainees in the room. The others were in orange, including a heavily tattooed man being visited by a woman and baby, who crawled across the table between them. All detainees are in blue, orange and red uniforms — the color is determined by security risk classification, low, medium and high, respectively.

The Villalobos brothers lived with their mother in Honduras. After their cousin was murdered and they were threatened, they fled and rode atop trains until they got to the border and turned themselves in, Alex said. They were first sent to Victorville, and then transferred to Adelanto.

At Adelanto, detainees perform much of the manual labor that keeps the camp operating, at a rate of $1 a day (a recent lawsuit pending in federal court in California alleges that GEO’s $1 a day rate amounts to “systematic and unlawful wage theft”). Wilson works in the kitchen, Alex said. The brothers use their earnings to pay for phone calls to their mother and to buy food from the commissary. But Alex hasn’t been working because he broke his arm playing soccer.

Adelanto is divided into two wings and houses on average about 1,500 total detainees. The larger prison-like West Wing has four and eight-person cells, and the dormitory-like East Wing has larger cells without bars. The wings are not strictly segregated by gender (although individual housing units are), but West houses mostly men and East women.

Immigration judges — employees of the Department of Justice — hear cases in courtrooms in both wings. I visited the courtroom in the West Wing, where a photograph of a beaming Trump hung on the wall.

A list of 104 cases being heard that day was posted behind a glass panel. A single judge was hearing 10 cases that day in East, while five were overseeing 94 in West.

Russell Jauregui, a staff attorney with the San Bernardino Community Service Center, was there to represent Alex’s brother Wilson. He was sitting among a group of nine detainees in two rows, all in blue uniforms and from Latin America or South Asia. Wilson looked younger than his 18 years, and during the hearing he appeared shell-shocked.

The Villalobos brothers have a difficult case because of Sessions’s move dispensing with protections for victims of gang violence. Jauregui is arguing for asylum based on religious persecution, but today’s hearing was strictly routine. The brothers’ cases are being heard separately, and their attorney asked the judge to join them. She said she’d consider it and would decide at a later date. The whole thing was over in five minutes.

The majority of asylum seekers at Adelanto have traditionally been Mexicans and Central Americans, but a growing number of claims are filed by asylum seekers from Africa and Southwest Asia, especially Sikhs claiming religious persecution at the hands of the Indian government, said Luis Suarez, policy coordinator for the Inland Coalition and an immigrant from Mexico himself.

Detainees can get bonded out, but the price is typically steep. Bonds for people from the local community who are seeking to stay in the United States but aren’t filing for asylum can start at $1,500. That amount can easily climb sharply for asylum seekers from Africa and Asia. “Bonds are higher for people ICE considers to be flight risks, and they consider almost everyone a flight risk,” he said. “We used to have a lot of local people whose family could bail them out, but now we have a lot of people who have no roots in the community and no access to resources. They can get lost in the system.” He said one Nigerian asylum seeker had bond set at $80,000 and had been at Adelanto for two years.

In the visitors room, I also spoke with Jibirine Yaro Amadou, a muscular man in his 30s from the West African country of Cameroon. He’d met Alex at a holding cell on the U.S.-Mexico border and they were also together at Victorville. He advocates for the repressed English-speaking citizens of his country, where the majority of people, including much of the ruling elite, speak French.

Following a protest he attended, Amadou’s sister, also an activist, was killed by security forces. Then police went looking for Amadou at a friend’s house and when they didn’t find him, they killed the friend, he said. He was able to flee the country only because a local police commissioner he knew got his passport stamped and took him to the airport.

Amadou traveled to Nigeria, and then made his way to Ecuador. From there he went by bus to Colombia, where the government told him he was not welcome. He traveled by bus with about 40 Africans and after being robbed by an armed gang when going through the Darien Gap, a lawless stretch of jungle on the border of Colombia and Panama, reached Panama City. Approximately six months after fleeing his homeland, Amadou turned himself in at San Ysidro, Calif.

He was sent to Victorville — a guard there told him “I was worse than the criminals because I’d broken the worst law of all, crossing the border” — before being transferred to Adelanto.

Like many detainees, he highlights the poor food, such as still-frozen taco shells, and lack of medical attention. “I write a request to see doctor every day, but I haven’t been able to see one for six weeks,” he said. “I’ve asked for medicine, but the only thing they have given me is ibuprofen.”

Our conversation was interrupted by the staffer sitting at the front desk. He read the last names of the detainees in the room. “It’s time,” he said.

*****

The country’s booming immigration detention complex, of which Adelanto is a cog, long predates the Trump administration. Modern immigrant detention originated with the 1980 Mariel boatlift from Cuba to Florida, during which more than 100,000 Cuban refugees sought asylum in Florida. The event is often remembered as a testament to American generosity toward immigrants, but it resulted in huge numbers of refugees being detained in hastily erected camps.

The detention complex picked up steam with the Reagan-era war on drugs, which made narcotics felonies mandatory grounds for detention and deportation. It sped up with 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, when terrorism and immigration policy merged in the Clinton-era Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act.

That law expanded the number of offenses that called for mandatory detention and deportation, and made violations retroactive. As a result, if you had been convicted of a felony at any time prior to 1996, it was now grounds for deportation. It also stripped permanent residents of most protections and tossed them into the same legal category as other noncitizens.

The 9/11 attacks launched a new immigration crackdown and gave birth to ICE. The early Obama years saw more transparency and better standards at detention camps, said Silky Shah, director of the Detention Watch Network, but by the end of his administration the size of the detention complex had swelled. “That’s when we get the idea that detention equals deterrence,” Shah said.

If Trump didn’t create the immigration detention complex, he has expanded it. Violating immigration law is a civil offense, but in April 2018, the Trump administration announced a “zero-tolerance” policy that called for the criminal prosecution of anyone who enters the country illegally. That’s what led to family separations at the border as parents are detained for prosecution while their children are held in shelters, or housed with sponsors.

In the days leading up to last month’s midterm elections, the president spent $200 million to dispatch 5,800 troops to the border to confront thousands of Central Americans in a caravan still hundreds of miles away. At the U.S. border near Tijuana, members of the caravan were met with tear gas shot at them by the Border Patrol. Pictures of two young Honduran girls fleeing a cloud of 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile, a chemical agent the United States and most countries have agreed not to use in war, made its way into countless news outlets.

“Immigration has been fused with repression,” said Emilio Amaya, executive director of the San Bernardino Community Service Center, which offers legal advice to detainees in Adelanto. “We’ve gone from bad to worse.”

*****

Today, Adelanto is one of more than 200 detention facilities in a nationwide network used by ICE. The agency only owns and runs a handful of these. It allows state and local governments to operate the rest, and they subcontract with private prison firms like GEO to directly manage the facilities.

State and local governments receive a modest revenue stream in the form of a “bed tax” paid by the private prison companies. The town of Adelanto, for example, nets about $200,000 per year in bed taxes. The detention center also employs about 400 people, mostly in security jobs.

This process whereby states and cities serve as middlemen means private contractors are “effectively insulated from government scrutiny,” concluded a 2018 report by the ICE Inspector General’s office. As a result, the agency “has no assurance that it executed detention center contracts in the best interest of the Federal Government, taxpayers, or detainees.”

Adelanto opened as a state prison in 1991 and was converted to an immigration camp in 2011. Since then, about 75,000 detainees have been held there, mostly for short periods. The population is a mix of immigrants labeled as deportable by the federal government and picked up in ICE sweeps, and asylum seekers who turn themselves in at the San Ysidro Port of Entry on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Adelanto has been a gold mine for contractors. GEO Group signed a five-year deal in 2011, guaranteeing payment for a minimum of 75 percent occupancy at $99 per detainee a day. An amendment the next year sweetened the deal: ICE agreed to pay a daily rate of $111 per detainee. GEO inked a new deal with ICE in 2016, but its terms are not known. The ACLU and the Inland Coalition have been trying unsuccessfully to get the latest contract through a Freedom of Information Act request for more than a year.

(A GEO spokesman refused to disclose the terms of the current contract, saying ICE should be contacted. An ICE spokesperson advised that a Freedom of Information Act request would have to be filed to obtain the contract.)

A host of subcontractors are involved as well. Correct Care Solutions — a firm facing a deluge of lawsuits alleging wrongful deaths and denial of treatment — provides medical and dental care at Adelanto.

Keefe Supply Co. runs the commissary, where detainees pay $5 for a four-ounce package of Maxwell House coffee (or $4.10 for the equivalent amount of Keefe’s own brand). SecurTel runs phone services, charging detainees 11 cents per minute for domestic calls. Bail bond companies charge 10 percent of the price of the bond. BI Inc., a GEO subsidiary, charges bonded detainees $350 a month for ankle bracelets.

Most immigrant detainees lack significant financial or legal resources and have few political champions, since they can’t vote, and Adelanto’s remote location also poses oversight challenges. Nonetheless, the facility has been criticized for its health and safety record.

In 2011, an ICE contractor reported lengthy delays in health appraisals, according to a story in the magazine Foreign Policy. The following year, a detainee named Fernando Dominguez Valdivia died as a result of “egregious errors” by medical staff, an ICE investigation found. Another preventable death of a detainee occurred in 2015. That prompted 29 members of Congress to send a letter to ICE requesting an investigation into health and safety concerns.

From December 2016 to July 2017, five people attempted suicide at Adelanto.

Last year, three detainees died at Adelanto over the span of three months, including one from suicide. ICE investigations uncovered deficiencies in the medical care provided to two of them.

Sergio Alonso Lopez, 55, a Mexican national, vomited blood and was taken to a hospital in Victorville on April 1. He died 13 days later due to issues including cirrhosis of the liver, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypertension and a history of substance abuse. Lopez’s death report shows that when he was first admitted to Adelanto in February, he said a doctor had told him he might have cirrhosis during a previous hospital stay.

Later that month, Adelanto’s clinical director, who had given Lopez his intake physical, received laboratory test results showing abnormal liver function and possible cirrhosis, but took no action in response. Lopez’s liver problems went unaddressed until a previously scheduled appointment with a different physician on March 30 — two days before his final emergency hospitalization.

Osmar Epifanio Gonzalez-Gadba, a 32-year-old Nicaraguan, committed suicide by hanging, using his bed sheet, about three months after arriving. Gonzalez appeared “psychotic and refused to eat” and was “illogical, tangential and delusional,” according to a doctor.

Vicente Caceres-Maradiaga, a 46-year-old Honduran, died of a heart attack in an ambulance on the way to the hospital.

A Department of Homeland Security Inspector General’s report released in September — following a rare unannounced inspection — revealed “significant health and safety risks” at Adelanto. Its inspectors had found nooses made of braided bedsheets in 15 cells. The nooses were used for suicide, one detainee told DHS, adding that guards laugh at people who try to kill themselves and mock them as “suicide failures.”

Inspectors found improper use of isolation — including unwarranted shackling of detainees — and abuse by GEO guards. DHS inspectors found 14 detainees in “disciplinary segregation,” all of whom had been placed there “inappropriately” without having been found violating any rules. Some in segregation were needlessly handcuffed and shackled. One detainee in segregation was left in a wheelchair for nine days, without the ability to sleep in a bed or brush his teeth.

Mario Perez, a former Adelanto detainee from Mexico, told me that as one of the only detainees who was fluent in English, he became an advocate for others, writing up formal complaints to the camp administration, mostly about the poor medical care. “They treated almost everything as short term,” he said. “If it was really serious and there was no other options they would send you to an outside specialist or hospital, but usually they’d just give you ibuprofen.”

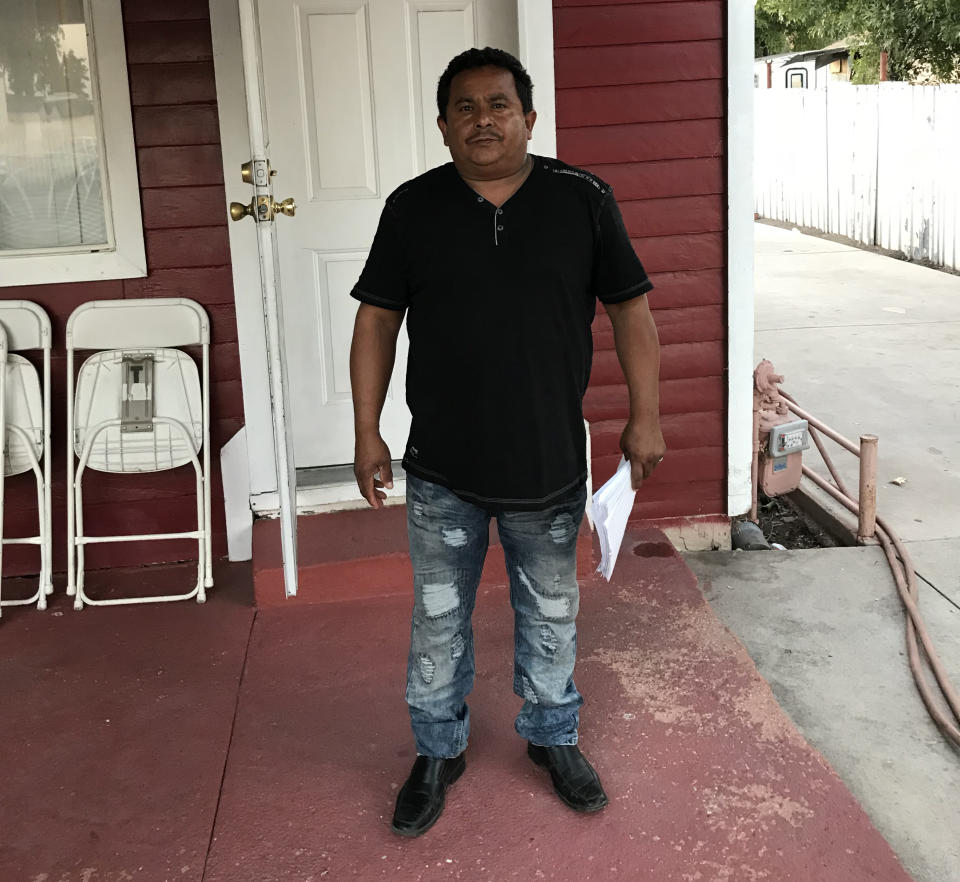

Unless it results in death, cases of poor medical care rarely make their way into public government reports, but they too can be serious. I spoke with Rufino Ortuno Benitez, who was released from Adelanto in May. Originally from Mexico, he’s been living in San Bernardino for the past 16 years.

He almost had his foot amputated as a result of botched medical care, he told me as we sat on a stained tan couch in the living room of his small wood frame house. In the next room his wife was tending to several pots and pans on the kitchen stove. The couple have four children who live with them.

A squat man wearing blue jeans and black boots, Ortuno said the sheriff’s office picked him up at his home one night in February, around 8 p.m. because he hadn’t paid a traffic ticket. He acknowledged having been involved in a traffic accident, driving without a license and having a prior DUI. After spending a night in jail, he got sent to Adelanto. “When I was taken in at the sheriff’s office, I overheard an officer calling someone and saying, ‘I have a gift for you’,” he said. “When they released me the next morning, ICE was waiting.”

Ten days after he arrived, Ortuno’s left foot became infected, a result he says of the detention center’s “filthy shower area.” He showed me a photograph taken during his detention that showed his swollen and inflamed foot, which had turned green and purple. Ortuno said he went a week without medical attention other than ibuprofen and was sent to a hospital only after cellmates threatened to protest if he wasn’t treated.

“They tried to put cuffs on my feet when I was sent to the hospital and they didn’t fit,” Ortuno said as he rifled through a stack of administrative and medical papers with the logos of GEO and Correct Care Solutions. “The doctor at the hospital told me he nearly had to cut my foot off because of that and the amount of time I went without treatment.”

To save it, the doctors grafted skin cut from Ortuno’s thigh onto his foot.

Ortuno had a landscaping job prior to being detained, but he’s still in pain and has trouble walking. He’s been out of work since he was released. He has a Feb. 7 date in immigration court, where he plans to make a plea for asylum, saying his home town in Guerrero state is dominated by violent drug traffickers. “I’m not a delinquent,” he said. “I have no grave offenses, and I’ve worked and paid taxes since I’ve been here. It’s my only chance.”

In response to questions about Adelanto, ICE sent a general statement saying the agency “is committed to providing for the welfare of all those entrusted to its custody and to ensuring all detainees are treated in a humane and professional manner.”

The “facilities that house ICE detainees must meet rigorous performance standards, which specify detailed requirements for virtually every facet of the detention environment,” ICE said in its statement. “The safety, rights and health of detainees in ICE’s care are of paramount concern and all ICE detention facilities are subject to stringent, regular inspections.”

Through DCI Group, a Beltway public relations firm, GEO Group sent a lengthy reply to questions, including on allegations of poor food and medical services. “Around-the-clock medical and mental health services are available to all detainees and medical staff on site [at Adelanto] includes 21 registered nurses, 26 licensed nurses, a physician, eight mental health specialists and two dentists,” the statement said. “The facilities we manage on behalf of ICE also deliver high-quality food services with three daily meals based on menus that address a variety of dietary preferences and needs and are reviewed and approved by a registered dietician.”

As to the Inspector General’s damning report on Adelanto, DCI group sent a response GEO Group released last October. “While we believe that a number of the findings lacked appropriate context or were based on incomplete information, we have already taken steps to remedy areas where our processes fell short of our commitment to high-quality care,” the statement read. “For the instances in which we have identified the standards were not properly met, GEO immediately worked with ICE to rectify procedures and has already implemented corrective actions”

The statement also said GEO is “conducting an in-depth review with our third-party medical services subcontractor to ensure all medical and dental care is provided at the highest quality and in a timely manner, and to hold accountable those who are not meeting these expectations.”

Correct Care Solutions, the firm providing the medical and dental care at Adelanto, did not reply to requests for comment.

*****

Vicente Caceres-Maradiaga, a 46-year-old, was the facility’s last detainee death.

The coroner’s investigation states that on entering Adelanto on May 22, 2017, Caceres-Maradiaga had severe high blood pressure, and was admitted into the detention center’s medical facility and evaluated by a doctor. After being given medication, his blood pressure readings fell, and he was released into the general population. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment three to four weeks later.

That never happened. He collapsed less than two weeks later, on May 31, 2017, while playing soccer in the facility’s exercise yard, and died en route to the hospital.

The Inland Coalition and the ACLU requested the autopsy from the local coroner’s office, but it took a year, and the help of local officials, to get it. The coroner determined that Caceres-Maradiaga died of heart disease.

ICE has yet to release its detainee death review on what happened to Caceres-Maradiaga. These reviews assess whether ICE and its contractors followed proper procedures.

His widow, Maria Isabel, says he came to the U.S. in 1999 and brought her four years later. “He always worked hard, in construction,” she said during an evening visit to the small home in North Hollywood that she shares with a friend and the couple’s 21-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter.

She moved into the house shortly after her husband’s death because she couldn’t afford rent on her own apartment. Her kids share a room, and another boarder lives in the house as well.

“It all happened so fast,” Maria Isabel recalled as we sat in the living room around 7 o’clock, after she’d returned from her job as a housekeeper. “He left the house around 6 in the morning to go to work. I left for my job and a few hours later he called to say he’d had a problem. I didn’t understand then, but that night he called from Adelanto.”

Maria Isabel said her husband had problems with the police, but she didn’t know exactly what for. (Records show he had criminal convictions for a DUI and fraud.) “He had paid bond and was doing community service and going to court every two months,” she said. “Everything was normal.”

She said they talked for a few minutes most evenings. After a few days he started complaining about shortness of breath. “He didn’t have any problems before he went in, he worked every day and he ate well,” she recalled. “Maybe it was fear or tension. I spoke to him the night before and he said they were giving him some sort of medicine but he was fine.”

When Adelanto called her, she thought it was to say her husband was coming home. Instead, she was told he was dead.

A few weeks later, Maria Isabel got a letter from Adelanto — she’s not sure if it was from GEO Group or ICE — offering condolences for the death of her husband. It’s the only official communication she’s had. “They did nothing for us,” she said. “The Honduran consulate contacted them for us and they were supposed to send his belongings, but we never received anything.”

The consulate paid for her husband’s body to be shipped to Honduras. His family buried him there.

The Project on Government Oversight’s Katherine Hawkins and Nicholas Trevino contributed reporting and research.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: