Project Aspire, the largest project in downtown Asheville, aims to find its footing

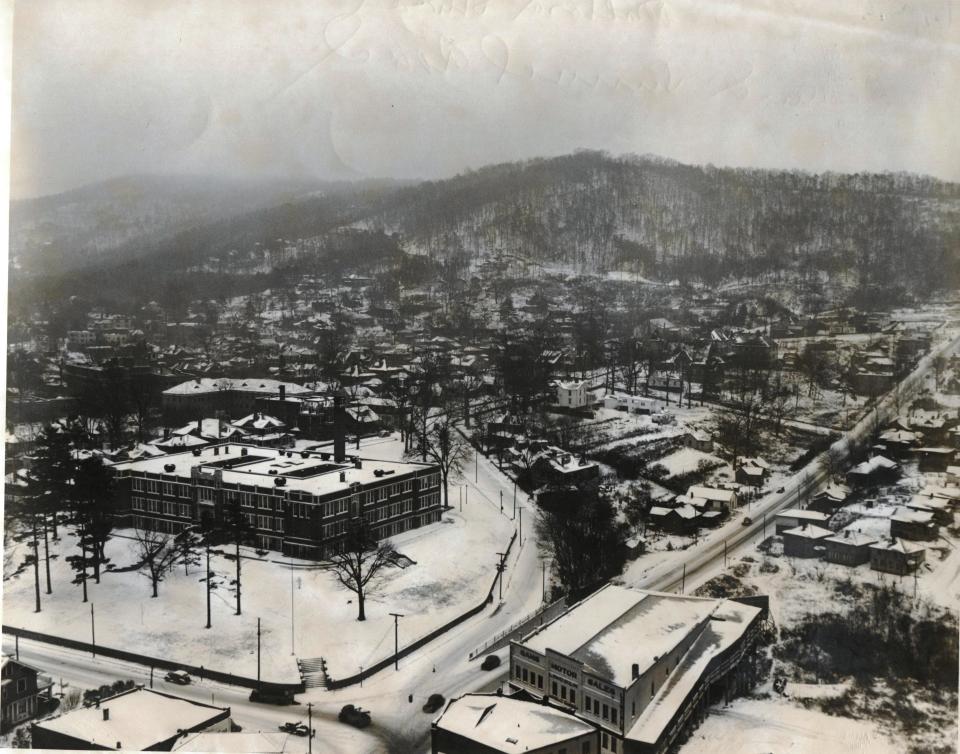

ASHEVILLE - In the northeast corner of downtown Asheville, Douglas Ellington's architecture has a commanding presence over the city skyline with the dome of the First Baptist Church and City Hall's iconic, red-tiled roof.

But that distinctive skyline could change if Project Aspire, an ambitious, sprawling, mixed-use development, is built.

In a collaborative effort between First Baptist Church of Asheville and YMCA of WNC, Project Aspire was approved by City Council late last year to redevelop 10-acres of land near the heart of downtown Asheville. The project is the largest master plan ever approved in the Central Business District, according to city staff.

If built to its proposed maximum height, two of the buildings — both projected to be 19 and 20 stories, respectively — would be the tallest in Western North Carolina.

Six months after its approval by City Council, the project is embarking on what could be a nearly 10-year process to bring affordable housing, a new YMCA building, office space and the tallest hotel in WNC to a 10-acre parcel, all of which sits next to the historically Black East End/Valley Street Community — drawing comparisons to the urban renewal projects that uprooted and displaced people in those neighborhoods decades ago.

Plans to address parking? Answer Woman: Downtown traffic impact of Project Aspire? Any plans to address issues?

A 'looming' hotel and urban renewal

Even as the project's master plan was approved in 2023, the process faced significant criticism — much of it coming from residents of the historically Black East End/Valley Street Neighborhood.

"Aspire will raise taxes on the East End community, which is another form of redlining and eminent domain and all of the negatives towards taking property from Black people," East End/Valley Street resident Kimberly Collins said during the Sept. 26 City Council meeting.

Renee White, president of the East End/Valley Street Neighborhood Association and vice chair of the Asheville-Buncombe Community Land Trust, said the neighborhood took particular issue with the height of the 20-story hotel.

White said they "certainly do not want that obstruction of view and that type of height," noting that addressing those concerns with the Greenville, South Carolina-based Furman Co. has proved difficult. She said that all of the neighborhood's meetings with the company have frustrated her.

The community was not initially told of the plan to place a hotel on the property, White said.

"I definitely don't want it to be a infighting type situation," White said of working with community organizations on Project Aspire. "It needs to be a situation where we're at the table, both sides, and that we're able to come up with some workable medians that are somewhat satisfiable to everyone involved."

"I just don't see that happening with the developer that they're currently working with," she continued.

The plot of land set aside for the hotel also raised concerns.

The First Baptist Church Building was one of fewer than than 20 buildings selected to be saved as part of the 1960's Civic Redevelopment Urban Renewal Project. The project displaced 145 families, of which 42 — or 29% — were families of color, according to Renewing Inequality, a University of Richmond web service compiling the history of urban renewal across America.

In the late '60s, the adjacent property, David Millard High School, and three houses were torn down and converted to what is now known as 1 Oak Plaza. The property was sold in 1977 to three local lawyers who converted it to an Asheville office for then Gov. Jim Hunt, according to past Citizen Times reporting.

The land eventually sold to First Baptist Church in 1994.

A collaboration 6 years in the making

While much of the development was publicly announced in early 2023, the project has been in the works for nearly six years as the YMCA and First Baptist sought to bolster their community facilities.

One morning in early February, the basketball courts, pools and day care facilities of the downtown Asheville YMCA — known as the regions flagship facility — were teeming with activity. The hallways seem more like people highways, with a stream of members coming and going — greeted with "good morning," "hello" and "how are you?"

The YMCA of Western North Carolina serves roughly 43,707 members, and the Asheville location is one of the most active in the region, despite being one of the older locations, said Paul Vest, CEO of the YMCA.

Despite multiple renovations to the 1970 facility, demands have changed, and the needs of the building are more than just gyms and locker room space — where the current layout of the building has made expansion difficult.

"We don't have really any space to do diabetes prevention, LIVESTRONG, or cancer survivorship or any of our health-related programs," Vest said from the hallway of the YMCA.

The new building would have at least 10,000 more square feet of space than the current nearly 50,000 square feet at the downtown Asheville YMCA.

Down the block, a similar discussion was taking place starting in 2018.

"You know, it was just sort of serendipitous. We kind of crossed paths and found out that we were both sort of going down the same path," said Scott Hughes, a former deacon chair at the church. "Introductions happened, and conversations began."

The Ellington-built First Baptist has expanded and undergone multiple renovations over its 97 years.

Now boasting a music school, day care facilities, a food pantry, community gathering space and acting as a temporary home base for the Asheville Symphony Orchestra, the 1927 church building is constantly active and requires maintenance.

The required upkeep is visible in the small things, such as damage to the carefully designed ceiling in the main sanctuary, said Hughes, who describes his role as "congregational liaison" to the Aspire project.

Between 2017 and 2021, the building lost over $800,000 in value, Buncombe County Property Records show.

"You're constantly having to feed it in big numbers for a facility this size, this ornate," Hughes said of maintaining the historic building.

"Everything is very expensive. So, it's going to have long-term needs, but we want to celebrate them," Hughes said.

Inverting the hotel model

After joining forces, the YMCA and First Baptist contracted the Furman Co. to help develop a project to include residential space, the new YMCA building and other amenities like a pharmacy and pediatric care center.

The project didn't just require a vote from City Council and Asheville planning boards, it required those at the church to be on board with the project, Pastor Mack Dennis said. The turnout showed interest in a project.

Furman Co. stepped in to help guide the process, both in terms of deciding to build the residential space and financing for the project.

"We were being entrusted with the mission objectives of the partners, and one of those objectives was to do something for the community benefit beyond just their doors," Furman Vice President Robert Poppleton said.

After bringing Furman on board, First Baptist made the decision to sell the 1 Oak Plaza property to a hotelier. The organizations told the Citizen Times the sale would finance elements of the housing development and help provide funds for maintenance to the 1927 church, Poppleton said.

Dennis posited: What if all new hotels in Asheville came with the motivation for new housing and backing of two Asheville based nonprofits?

"They buy the land, and they build the big thing and they make the money," Dennis said of typical developments. "And this really inverts all of that. Even the hotel piece."

Will Aspire's housing really be affordable?

Asheville's Fair Market Rent is the highest for North Carolina metros, with a one-bedroom apartment going for $1,496 a month, according to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Across North Carolina and its surrounding states, only the Atlanta and Washington D.C. metros have higher Fair Market Rents for one-bedroom apartments than Asheville.

Current project plans include the possibility of at least 130 apartments that are deemed "affordable" at 80% of area median income. In Asheville, one would have to earn $47,600 a year to qualify for an apartment at 80% AMI, according to HUD data.

"We know people are struggling with housing. They're struggling with childcare. They're struggling with being able to live well and have an integrated life," Dennis said.

However, some people remain skeptical of just how affordable the development would end up being.

According to a recent study by THRIVE Asheville, a local nonprofit, 80% AMI projects in Asheville have historically missed the median income for Asheville residents who are Black or Hispanic.

The estimated median income for Asheville's Black households is $28,628, according to the American Community Survey 2022 5-year estimate. The estimate is over $35,000 below the estimated $63,810 area median income for Asheville households.

The report's equity concerns have led to the pause of the Land Use Incentive Grant, or LUIG, an affordable housing funding tool used by the city. Two-thirds of the projects funded through LUIG have only provided affordable housing at 80% AMI.

For her part, White believes a collaboration between the Asheville-Buncombe Community Land Trust, or a similar nonprofit, could bring deeper affordability.

"Maybe doing some kind of partnership, even with the land trust, so that we can ensure that some Black people are able to move in," White said. "With that type of AMI, I mean, really? Who can afford it?"

Aspire included in reparations?

Considering the history of urban renewal, Dennis said conversations between First Baptist and East End/Valley Street Neighborhood Association have been difficult, but they have opened up new doors in the community.

"We can't fix what happened. We can't make it right, but we can still make something beautiful out of this," Dennis said. "And if early conversations are any indication, I think we have a lot of new friendships and new possibilities and opportunities to look forward to on both sides of the street."

Sitting in the sanctuary of First Baptist in January, Poppleton said Furman intends to follow a commitment to continuing community engagement.

"I hope that we have developed some level of trust from what we've already done in terms of community outreach," Poppleton said. "And, you know, projects move at the speed of trust."

In White’s view, the Aspire property, along with other urban renewal properties, should be included in discussion with the reparations commission.

The Community Reparations Commission is a city of Asheville commission established to create recommendations to repair damage caused by public and private systemic racism in the city.

"What does that look like in terms of reparations? What does that look like in terms of if that land was actually urban renewal property? Then what does it look like for them to be able to give back," White said.

More: Asheville Reparations: Members hear final 'equity audit:' 108 new recommendations

The next step? Funding

The project is facing other hurdles, chief among them is securing funding.

The estimated budget for the first phase of the project could run up to $200 million, Poppleton said, and would break ground with a parking deck. The company would likely request a public-private partnership to leverage public funding to build the parking deck, selling the project as good for business and housing, Poppleton said.

"What we are saying is this private investment will produce for the community of Asheville several new revenue streams that will feed into the community. Whether it be property taxes, or hospitality tax, or a portion of sales tax revenues," Poppleton said of the use of public funds toward the project.

To help with upfront cost on the project, the YMCA has sought funds from the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority Legacy Investment from Tourism, or LIFT, to pay for predevelopment activities.

Project Aspire has asked for $627,263 in LIFT funds, according to the Phase 1 application to the BCTDA. The project is currently in Phase 2 of the LIFT fund process, the BCTDA confirmed March 22.

Nearly every step of the way during construction and planning, the project will continue to see community and city feedback through the Design Review Committee and Planning and Zoning Commission.

Dennis, sitting in the space he often speaks from every Sunday, wondered if the project would become a model for community collaboration around the country.

Though still early days for the project, the East End/Valley Street Neighborhood Association will continue the dialogue with stakeholders.

"We've decided that we are going to sit back down with Project Aspire and look at what it looks like to get some benefits out of it for our neighborhood, for our community and especially for our Black community," White told the Citizen Times.

More: Asheville East End church saved from demolition, finds 2nd life as affordable housing

More: Downtown Asheville homeowners live amid 9 illegal Airbnb's; despite reports, no fines

Will Hofmann is the Growth and Development Reporter for the Asheville Citizen Times, part of the USA Today Network. Got a tip? Email him at [email protected]. Please help support this type of journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Project Aspire still looks to find its footing amid community concern