Record-breaking Category 5 Hurricane Beryl wouldn't be possible without climate change

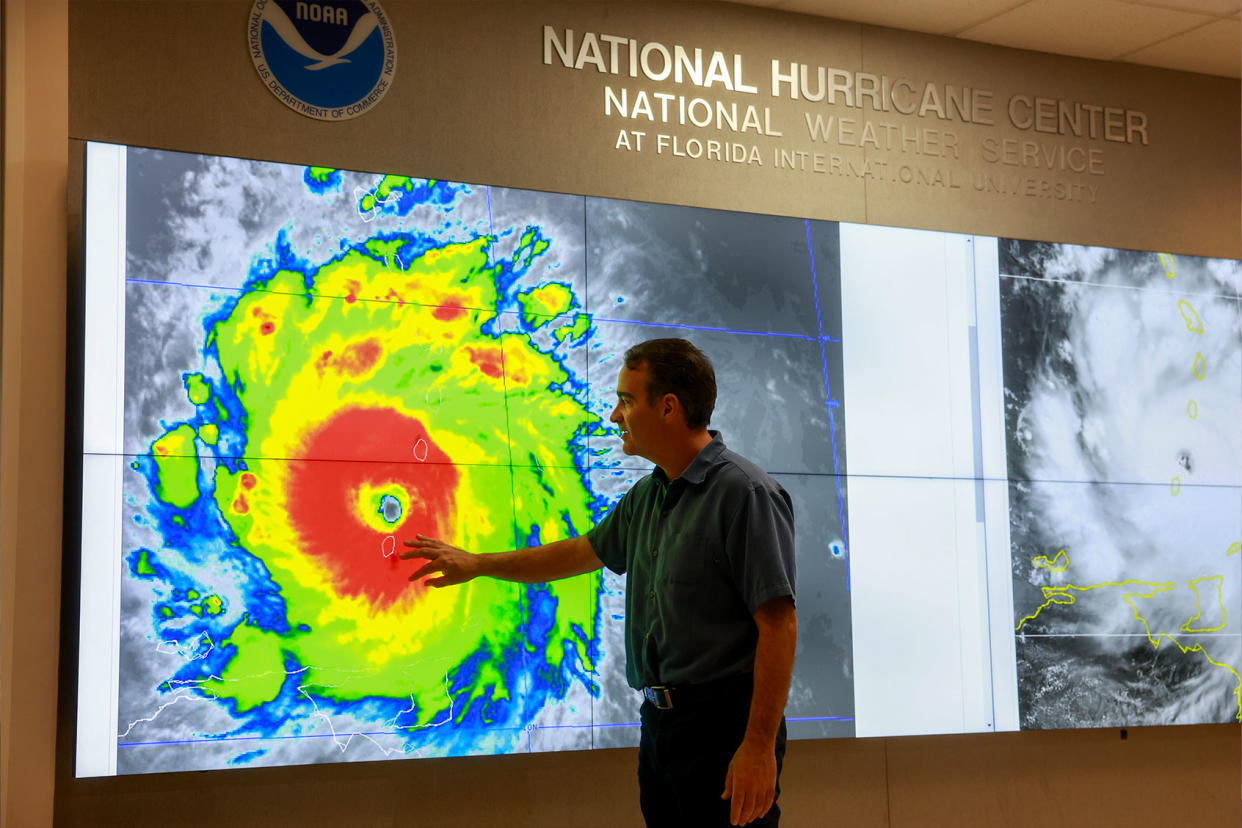

In late May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the top hurricane forecasting body in the United States, published a report forecasting the most active hurricane season yet. Now that the season has begun, Hurricane Beryl — the first named hurricane from 2024 — arrived last week, and is already breaking records for its early intensity.

It's the first Category 4 storm to be recorded in the month of June since records first began being kept in 1851. Late Monday night, Beryl strengthened to a Category 5 as its winds increased to 165 mph (270 kph), razing southeast Caribbean islands as it heads toward Jamaica, according to AP News. Experts who spoke with Salon agree on one thing: Hurricane Beryl is powered by global heating driven by burning fossil fuels.

Michael Wehner, a senior scientist in the Computational Research Division at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, told Salon that the majority of tropical cyclone experts perceive Hurricane Beryl as "a unique, unusual and record-setting storm."

"The unusually warm sea surface temperatures and the developing La Ni?a conditions play a significant role. Global warming has increased these ocean temperatures adding to the natural variability," Wehner said. "Quantifying the contribution of climate change to the intensity of this storm will require detailed calculations, which will take some time to produce."

"Climate change and, in particular, warming oceans, are fueling ever-more-powerful hurricanes, in the Atlantic and around the world," Dr. Michael E. Mann, a professor of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, told Salon. "For each 1°C of warming (which is roughly how much the oceans have warmed) we observe a roughly 12% increase in peak wind speeds, which corresponds to a roughly 40% increase in peak intensity (which is proportional to the third power of the wind speak)."

Adding that this increase is not only detectable "it’s now readily observable," Mann added that this is why "I have endorsed the creation of a new category, Category 6, for the very strongest storms we are now witnessing."

Scientific data makes it clear that this storm isn't just an anomaly, as these storms would be neither as frequent nor as intense if humans were not overheating our planet by pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

"We estimate from model simulation studies that for a 2o Celsius global warming scenario, hurricanes in the Atlantic basin will be about 3 percent more intense in terms of surface wind speeds, and about 15 percent more intense in terms of their near-storm rainfall rates," Tom Knutson, a senior scientist from GDFL and NOAA who oversees a website tracking global warming and hurricanes, told Salon.

Although these anthropogenic changes have not yet been clearly detected in observations, "many hurricane metrics have increased in the Atlantic basin observations since the 1970s and '80s — such as rapid intensification, hurricane intensities, number of major hurricanes, and so forth," Knutson said.

It is difficult to isolate the specific influence of greenhouse gas emissions compared to other variables because the different factors have played out over many decades. Despite this limitation, however, the proof is still overwhelming.

"A clear trend and anthopogenic climate change influence has been detected in global sea level and in tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures; and sea levels over the past century are clearly rising along the U.S. East Coast," Knutson said. "Rising sea levels, all other things equal, will exacerbate coastal flooding from the hurricanes that do occur."

He added, "Future changes in the frequency of Atlantic hurricanes and major hurricanes remain uncertain due to the large range of projections in modeling studies, with some studies suggesting increases and other studies suggesting decreases, for example."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Dr. Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, further elaborated on how climate change worsens storms like Hurricane Beryl.

"The fuel for a hurricane is the atmospheric moisture: as it condenses it releases latent heat (the heat that went into evaporating the water in the first place)," Trenberth said. "Warmer air can hold more moisture at a rate of about 4% per deg F. The ocean all around is much warmer than normal in part because of climate change and in part because of favorable weather patterns. The later relate to the El Ni?o over the previous year that focus the main weather action into the Pacific."

To the extent that scientists are limited in their ability to ascertain the precise extent to which global warming is causing these storms, Knutson explained that it is because monitoring technology has advanced significantly over the past half-century.

"In addition to the confounding effects of natural variability and aerosol driven changes, which make it hard to detect the greenhouse gas-induced warming influence on Atlantic hurricanes, another problem is the changing/improving ability to detect and measure hurricane intensities and annual numbers over time, especially when we try to look at the pre-satellite era before the late 1960s," Knutson said. "This makes it very difficult to explore for century-scale trends due to greenhouse warming influence. An exception is for U.S. landfalling hurricanes or major hurricanes, where the long-term record is more reliable. In that case, there is no clear trend in their number (or the fraction of hurricanes that reach major hurricane intensity) since the 1880s."

As Beryl breaks hurricane records set in 1933 and 2005 — two of the busiest hurricane seasons in modern history — climate experts anticipate that this will be only the first of many super-storms to strike the Western Hemisphere in this summer, not to mention in the future. Our rapidly-heating world is only becoming more ripe for intense hurricanes.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report "clearly states that the most intense storms will get more intense," Wehner said. "There is clear evidence since that 2021 report that this is already happening."