Red tape traps teenagers seeking refuge in U.S.

Like most teenagers in the United States, Luis looked forward to his 18th birthday. Unlike most teens, Luis’s excitement was not about being able to vote or buy cigarettes or other American rites of passage associated with turning 18, but about the prospect of being released from custody and reunited with his family.

A little more than two months before his birthday, Luis, whose name has been changed to protect his identity because he is currently seeking asylum, arrived at the southern U.S. border after a long and dangerous journey through Mexico. His father had never been a part of his life, so when his mother fell ill and went to live in a church without him, Luis decided to leave his Guatemalan village, which had become ruled by violence, and seek work in Mexico. But not long after arriving in Chiapas, Luis met someone who told him that if he had family in the U.S., he should go there. Luis knew he had relatives in Atlanta and, though he had no idea how to get there, he set out on a journey to find them.

After turning himself in at the border, he was placed in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is tasked with the care of unaccompanied immigrant children. He was put on a plane and taken to live in a shelter-like facility in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., where a caseworker began collecting the paperwork necessary to request Luis’s reunification with his relatives in Atlanta.

With his 18th birthday looming, his caseworker told Luis they would have to get the documents submitted as quickly as possible, warning that if he wasn’t released before his birthday he could be sent to an adult detention center. The prospect of this made Luis start to panic but, he said, his caseworker insisted that he needn’t worry. “’We have time,’” he recalled her telling him.

So they proceeded to gather the paperwork and submit a request to ORR for Luis to be released to live with his brother-in-law in Georgia. As far as Luis knew, there weren’t any issues and, by the eve of his birthday, he says, the caseworker told him there was a plane ticket to Atlanta ready for him to leave that night. They were just waiting on a response from the government as to whether it was going to approve his case.

“I was happy because I was ready to leave,” Luis recalled. “I got ready with all of my clothes, my backpack…,” but as Luis and his caseworker made their way to the facility’s exit, she revealed to him some devastating news: His case had been denied.

Terrified and confused, Luis racked his brain for what he had done to suddenly deserve being treated like a criminal.

“All I did was turn 18,” he said.

Luis is part of a growing trend, observed in recent months by legal advocates and social service providers who work with ORR, of unaccompanied immigrant teens — most of them fleeing violence at home in Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador — being handcuffed, shackled and thrown into adult ICE detention, literally before dawn on their 18th birthdays. Most were in the process of pursuing asylum or other legal forms of refuge in the U.S.

Those directly affected by these changes constitute a relatively small but highly vulnerable population of young people known, in the parlance of the U.S. government, as Unaccompanied Alien Children, or UACs.

These are, generally speaking, foreign-born girls and boys under the age of 18 who have been caught — or, in many cases, turned themselves over to Customs and Border Protection — after entering the country illegally without a parent or guardian; hence the label “unaccompanied.” They are the victims of the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants generally, and in particular its focus on the violent MS-13 gang, which recruits teenagers from Central America.

The overwhelming majority of UACs who have arrived since 2014 have come from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, countries racked by poverty, corruption and brutal gang violence. Their journeys to the U.S. through Mexico often involve exploitation or abuse at the hands of traffickers.

The UACs might qualify for asylum in the U.S., but their status is complicated by the fact that they crossed the border illegally. Federal statutes and court rulings have established legal guidelines for how to treat this population of young people who’ve entered the country illegally but express fears of returning home.

A 1997 federal court decision known as the Flores Agreement required the government to release such children “without unnecessary delay” and make “prompt and continuous efforts” to reunify them with family in the U.S. while they make their legal case to stay.

Back then, the care of immigrant children was the responsibility of the Immigration Naturalization Service (INS). But in the aftermath of 9/11, the INS was dismantled, and most immigration and enforcement agencies were reshuffled into the newly established Department of Homeland Security. Not included under this broad new DHS umbrella, however, were the so-called UACs. With the passage of the Homeland Security Act in 2002, Congress incorporated the principles of the Flores Agreement and determined that custody should fall under the purview of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Congress’ concern for the welfare of these children was further codified by the 2008 passage of the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), which granted immigrant kids the right to legal protections while in ORR custody, and mandated that the agency ensure that children in its care are “promptly placed in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child.”

But the priorities that shaped the treatment of immigrant children over the past two decades have been subordinated to the Trump administration’s hard-line approach to immigration. In speeches, President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have singled out minors from Central America as threats who take advantage of “loopholes” in immigration laws to infiltrate the U.S. and commit crimes.

Approximately 150,000 Central American teens and children have been caught crossing the border and referred to ORR since 2014.

The Department of Justice estimates that there are currently 10,000 active MS-13 members across 40 U.S. states, a figure that has remained relatively stable since at least 2006, with the highest concentrations in New York, Virginia and the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. (Though the gang now has a much larger presence in Central America, it was actually established in Los Angeles in the 1980s by teens whose parents had fled a deadly civil war in El Salvador.)

Police in New York’s Suffolk County have attributed 27 murders to MS-13 members since 2013; the parents of two teenage victims from the heavily Hispanic town of Brentwood, on Long Island, were saluted by President Trump in January’s State of the Union. A recent report by the Washington Post suggests that the surge in unaccompanied minors from Central America has helped fuel recent violence by MS-13, as members target these vulnerable recent arrivals for recruitment.

But even ORR, in its own memo to the White House Domestic Policy Council, admitted that “the great majority of UAC in ORR custody do not pose a safety risk to the public and are not affiliated with gangs. Many UAC come to the United States to escape violence and gangs in their home communities.”

The same memo refers to a June 9, 2017, ORR review of the teenagers in its “secure” and “staff secure” facilities — the small number who have been determined to pose a potential risk to the community, or to themselves, or of fleeing custody. “From that review, ORR determined that of the 138 UAC in those facilities on June 9, 35 were voluntarily involved with gangs. Four additional UAC had reported that they had been forced into gang participation. In the context of the nearly 2,400 UAC in ORR custody on that date, this means that gang members were approximately 1.6% of all UAC in care.”

Nevertheless, a number of procedural changes at ORR, together with ICE’s enforcement policies, are creating what critics call an inescapable cycle of prolonged detention.

As an ORR spokesperson noted in a statement to Yahoo News, unaccompanied youths technically fall under DHS jurisdiction as soon as they turn 18. Still, legal advocates and social service providers who work with ORR say that in prior years ICE exercised discretion in how to treat them and would often sign off on alternatives proposed by lawyers or caseworkers in anticipation of their milestone birthday.

Under those agreements, 18-year-olds who were not deemed dangerous or a flight risk could be released on their own recognizance, or to family members, or placed in some kind of group housing, either with an ankle bracelet or with orders to check in at an ICE office regularly until their case has been resolved in court. A source in DHS who did not want to be identified confirmed that this had been the policy under previous administrations.

These so-called post-18 plans are still being prepared and proposed for clients who are on track to age out of ORR care, but advocates for the children say ICE is no longer considering them as an option.

The DHS source did not know how many teens have been taken directly into adult detention upon turning 18 under the current administration, nor could the source point to a specific policy change with regard to how ICE handles such cases. A February 2017 memo issued by then-Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly eliminated ICE’s prior list of enforcement priorities established by Kelly’s predecessor, Jeh Johnson, encouraging ICE agents to focus enforcement resources on certain categories of undocumented immigrants, including convicted violent criminals and recent border crossers.

By eliminating these priorities, Kelly implemented a new era of indiscriminate immigration enforcement, pursuing anyone and everyone who is in the country illegally, regardless of circumstance.

“I think Kelly and Trump were just in such a hurry to arrest everyone that they maybe didn’t think of the implications on these kids,” said the DHS source.

A class action lawsuit filed last week by the National Immigrant Justice Center accuses ICE of automatically transferring 18-year-olds from ORR to ICE custody without considering potential alternatives to detention. The suit argues that by failing to consider the least restrictive option available in the best interest of the child, ICE was violating a 2013 amendment to the TVPRA that extended such requirements to kids who turn 18 while in ORR custody.

Meanwhile, advocates suspect ORR is slowing the process of releasing children into the “least restrictive” situation, as required by law, so that more of them are aging out into ICE custody.

The ORR declined to provide Yahoo News with recent data on the number of immigrant teens in its custody who’ve been transferred immediately to adult ICE detention upon turning 18. It did, however, reveal the portion of unaccompanied children who’ve “aged out” of ORR custody in general, which, although small, demonstrates a clear upward trend from 1 percent in 2014 to 2.4 percent in 2017, increasing incrementally each year.

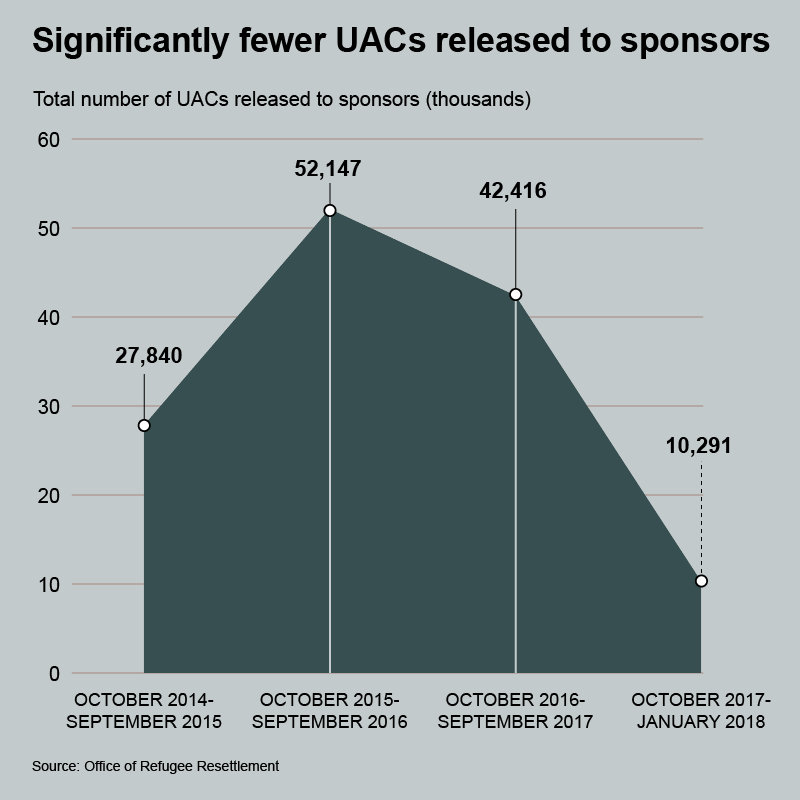

At the same time, according to data published on the agency’s website, the number of unaccompanied minors in ORR custody who’ve been reunified with a sponsor has decreased significantly across almost every state since October 2016.

One possible explanation is that family members, who may be undocumented themselves, are reluctant to come to the attention of DHS by volunteering as sponsors.

Arguably, though, the biggest effects on the reunification process stem from a series of policy and procedural changes implemented at ORR under the banner of what Director Scott Lloyd dubbed the agency’s new Community Safety Initiative. According to an August 2017 memo to the White House Domestic Policy Council, the initiative was created in response to “public and congressional concerns about the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, Central American street gang in American communities, and the involvement in that gang of some individuals who were previously in the ORR UAC Program.”

Among the changes imposed under the Community Safety Initiative was a new requirement that either Lloyd or his deputy director, Jonathan White, personally review and approve all requests for release of any UAC who, at any point during their time in ORR custody, had been housed in secure or staff-secure facilities.

At any one time, that is a small fraction of the total number of UACs in ORR custody; the great majority are in “shelter-level” residences. But the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit last month against Lloyd and others claiming that, under Lloyd’s leadership, “the process of reunifying the children in the plaintiff class”— that is, those who have at any point been placed in a secure or staff-secure facility, even if their stay there was ultimately deemed unnecessary and they were moved back to a less secure facility — “has ground to a virtual halt, trapping these children in highly restrictive government-controlled facilities.” (PDF)

The suit focuses specifically on New York, but the same trends have been observed by legal and social service providers that work with ORR around the country.

Nithya Nathan-Pineau is an attorney and senior program director for the Capital Area Immigrants’ Rights Coalition’s Detained Immigrant Children’s Program, which provides legal services to children in ORR custody in the Washington, D.C. area. Because two of the three facilities in the country that provide secure detention for kids in ORR custody are located in the D.C. area (the third is in Northern California), Nathan-Pineau and her colleagues are well suited to observe trends within that population. Before the NYCLU filed its lawsuit, she described similar scenarios of stalled cases and seemingly interminable detention.

“We have kids who’ve been trying for over a year to reunify with biological parents, and they’re sitting in secure detention,” she told Yahoo News. “I’m seeing more kids moving up to that higher level of security and not moving, and essentially getting stuck in secure or staff-secure. They may move between those levels, but we’re not seeing kids really get released to sponsors.”

In fact, she added, “we haven’t seen a reunification out of secure detention in over a year.”

Increasingly, allegations of gang affiliation — often based on information children disclose upon entering ORR custody, such as having been forcibly recruited or victimized by gangs either at home or along their journey to the U.S. — are leading to more secure and staff-secure placements, albeit often temporarily.

To bolster its new gang focus, the Community Safety Initiative calls for working with law enforcement to train residential facility staff and ORR-contracted social service providers who work with teens before and after release on how to identify gang affiliations, including cues such as clothing.

Someone who attended one of these training sessions and spoke to Yahoo News on condition of anonymity said the guidelines “felt a little bit more like profiling.” The potential for mistakes was, this person said, “deeply troubling,” because a misidentification could keep a teenager locked up for years.

As part of the intake process at ORR facilities, children have traditionally been encouraged to share all the details of their journey in order that those who may have been victims of trafficking or have otherwise fled particularly dangerous situations may be identified. Now, this person said, that information is being used against them, as staff are labeling kids as gang-affiliated at the mere mention of a gang, no matter the context.

“They may have been a victim of trafficking or may have known somebody who was in a gang,” but now “a staff member who attends one of these trainings where you have very limited information being presented by DHS, they can then designate that child as gang-affiliated and they go straight to secure. That was never a policy before.”

Such placements are subject to review, but “once they’ve gone to secure they cannot be released without their case being approved by [ORR] headquarters,” the source said, where their requests for release are languishing, unanswered.

“That is really devastating because kids who pose no threat and may have been the victims of horrific trafficking for years are now having their cases held up, and they’re not able to reunify in a safe environment because of these policy changes.”

Even detainees who aren’t flagged for secure facilities are spending more time in custody than before, says Nathan-Pineau, noting that ORR’s average stay in shelter-level custody was previously around 30 days. According to statistics posted to the ORR website, the average length of stay in shelter and transitional foster care during fiscal year 2017 was 41 days.

Robert Carey, who served as ORR director under President Barack Obama from April 2015 to January 2017, questioned whether the ORR’s new policies signaled a shift in the agency’s role toward more of a focus on law enforcement.

“My question is, does that really belong in child service agency?” he asked.

Carey also expressed concern about the trend toward transferring unaccompanied teens from ORR custody to adult detention as soon as they turn 18.

“Many of these children have been victims of violence and sexual exploitation, so to put them in an adult detention facility is an end to be avoided, not pursued, and not to be done lightly,” he said.

“Those policies are, to me, extremely politicized,” said Diane Eikenberry, associate director of policy with the National Immigrant Justice Center. “It’s not about the best interest of the kid. It’s a messaging tool for the political appointees to say to the White House, ‘We’ve got your back.’”

Eikenberry argued that prolonged detention — whether by ORR or ICE — undercut the “decades of recognition that it is inhumane to throw children in jail.”

So far, the clearest result prolonged detention appears to be having is deterring those who’ve already made the dangerous journey here from continuing to pursue legal claims of asylum.

“It’s really discouraging to see that because we believe that people have the right to seek asylum,” said Nathan-Pineau. “It’s not illegal to come to the United States to seek asylum. It’s never been illegal, and it shouldn’t be considered to be illegal now.”

Before he was taken into ICE custody, Luis said, his caseworker told him he’d have two options: “You can pay a lawyer and fight your case, or you can sign an order of deportation and go back to your country.”

“I was scared,” he told Yahoo News. “I didn’t want to go back to Guatemala, but I didn’t want to go to jail.”

Luis chose to fight his case and was taken to New Jersey’s Bergen County jail, which is contracted by ICE to house immigrant detainees. He was given an orange shirt and matching pants with the word “Prisoner” printed in big, black letters down one of the legs, and locked in a cell with an older man from Africa who Luis said initially shared his food with him and then angrily accused him of stealing it.

“The days inside passed very slowly,” Luis recalled. “There’s nothing to do; they don’t let you out, and the truth is, I didn’t know if it was night or day because you’re just totally enclosed.”

For the first few weeks, he didn’t have any communication with the outside world — including his family. He was allowed to make one free phone call when he first arrived, but when he called his relatives in Atlanta no one answered. He had no money for additional calls, so no one knew where he was. About two weeks in, Luis says he was given the option to work in the kitchen, and about a week later he was paid.

After more than two months behind bars, Luis was finally taken from the jail --— clad in his orange prisoner clothes, his wrists cuffed and shackled to a chain around his waist — to a courthouse in Manhattan for his first appearance in front of an immigration judge. He met with Alex Lampert, an attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services (BDS), part of a state-funded network of legal aid groups in New York that offer free representation in immigration court. The program, known as the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, or NYIFUP, was the first of its kind in the country.

Though a number of cities have similar local initiatives, New York has the only statewide program. So for unaccompanied teens in most other parts of the country, being transferred to adult ICE detention also means losing access to the legal services previously provided to them as minors in ORR custody.

With Lampert’s help, Luis was released on bond after three months of detention and is now currently living with a pastor in the Bronx. He has successfully petitioned for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, a legal classification available to certain undocumented immigrants under the age of 21 who’ve been abused, neglected or abandoned by one or both parents and for whom returning to their home country is not in their best interest. SIJS status will enable Luis eventually to petition the government for a green card.

In the meantime, Lampert added, he also has an asylum application pending.

Between his time ORR and ICE, Luis was in custody for approximately five months after he arrived in the United States. Still, he is lucky to now be pursuing these legal avenues for relief from outside the confines of detention.

“The detention itself is very coercive, by design or at least, by effect,” said Lampert, noting that, for many teens, as well as adults, the barriers imposed by being locked up make even cases that could easily be won outside detention almost impossible to pursue from behind bars.

On a recent Thursday last month, a teenage girl from Guatemala was shuffled into one of the immigration courtrooms in Manhattan for her first appearance before a judge since entering the United States seven months earlier. Her entire time in the country had been spent in custody, first by ORR for four months, followed by another three months in ICE detention. Her brown, layered hair fell slightly in front of wide eyes that darted around the courtroom as she waited for her turn to approach the bench. When her name was finally called, she stood no more than 5 feet tall and could barely raise her right hand from the shackle affixed to her waist.

Her lawyer, another attorney with BDS who declined to provide more details about the girl’s case, told the judge that her client wanted out of detention, and would accept an order of removal back to Guatemala. The judge asked both the attorney and the girl a series of questions that ended when, with the help of a Spanish interpreter, the girl told the judge definitively, “I just want the deportation order.”

And with that, in under 10 minutes, her prolonged detention in the United States was effectively over and she would soon be sent back to the country she’d fled seven months before.

Editor’s Note: This story initially cited data inaccurately claiming that “In October 2016, CBP referred 66,708 unaccompanied minors to ORR care — which is close to the number of kids referred to ORR during the height of the 2014 surge. Those numbers dipped dramatically during the first few months of 2017, reaching a low of 15,766 in April of that year, but have steadily started to climb back up to rates comparable with previous years, ranging between 34,000 and just over 40,000 each month since October.” Those numbers, since removed, reflected the total number of undocumented people apprehended at the Southwest border during that time period.

Read more from Yahoo News: