Republican who refused to certify Georgia primary a member of election denialist group

A Republican on the Fulton county election board who refused to certify the May primary election is a member of an election denial activist network founded by Cleta Mitchell, a Trump ally who aided his efforts to overturn the election in Georgia and elsewhere.

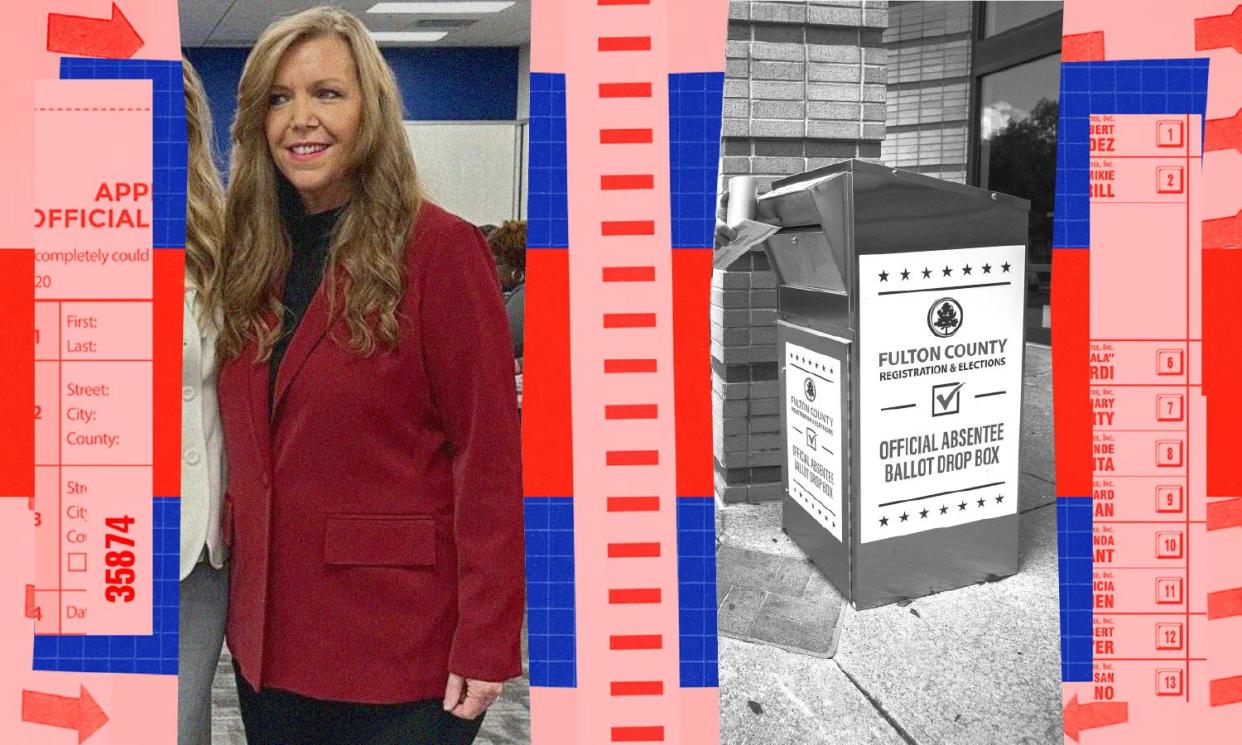

Julie Adams, who was appointed to the board in February, abstained from certifying the results of the May primary last month. Each of the other four board members, including the other Republican appointee Michael Heekin, voted for certification. No allegation of error or misconduct has been raised about the 21 May primary.

Related: Georgia elections board member denies plans to help Trump subvert election

Adams is the regional coordinator for southeastern states in the Election Integrity Network (EIN), a national group that has recruited election deniers to target local election offices. She helped start the Georgia Election Integrity Coalition after attending an EIN summit on election integrity in 2022, according to a publicly-posted biography.

She has also been affiliated with Tea Party Patriots, another election denialist group.

“Julie Adams’ role on the Fulton county election board makes as much sense as inviting a fox to a seat in the henhouse,” said Stephanie Jackson Ali, policy director at the New Georgia Project Action Fund, a left-leaning group focused on voting rights.

“Ms Adams has made clear – in her private work for the Election Integrity Network, in her recent lawsuit against the county board, and in refusing to certify the May elections – that she is not working to make elections stronger or build voter confidence. Instead, Ms Adams is beating the dead horse of fictitious stolen elections.”

She added: “We are concerned that Ms Adams and her cohorts will continue to push this narrative in November.”

Adams has been involved in efforts to promote the use of EagleAI, a software activists are using to challenge voters in Georgia and across the country. Election officials and voting rights groups have raised alarm about the software, which is also linked to Mitchell, saying it is not reliable. During a July 2023 call reviewed by the Guardian, Rick Richards, the software’s creator, said Adams would be one of the people leading the efforts to use the software in Georgia, “coordinating who does what”.

Aunna Dennis, the executive director of the Georgia chapter of Common Cause, a government watchdog group, said Adams’ refusal to certify the election was “definitely alarming”.

She said the episode showed “the dysfunction that it can create to the operations of actually ensuring fair and transparent elections” when election deniers are appointed to a board.

“It seems very tactical as well, and it does not uphold the oath of really what our election board members should be doing,” she added.

Republican officials elsewhere across the US have refused to certify elections at the local level, prompting legal action to compel them to fulfill their obligations. There is concern that such efforts this November could lead to a delay in certification of the presidential vote and create chaos after the election.

“I’m definitely concerned about what’s going to happen in November,” Dennis said. “It makes me concerned about the trend that may happen in those smaller counties where it may not be publicized and it may be far harder to find out if those things have taken place.”

Mitchell, who founded the Election Integrity Network, was on the infamous phone call in which Trump urged Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to overturn the election. A special purpose grand jury in Fulton county recommended she face criminal charges for her role in trying to overturn the election, but she was not charged.

On 22 May, the day after the legislative primary election, Adams filed a lawsuit against the Fulton county election board and the county’s election director in an effort to get access to more election information and a court order saying that boards of election members have the discretion not to certify an election. She argues that she was not allowed to do her job overseeing the election for the presidential primary in March. The suit is being supported by the America First Policy Institute, a pro-Trump group.

“It’s time to fix the problems in our elections by ensuring compliance with the law, transparency in election conduct and accuracy in results,” Adams said at the 28 May election board meeting explaining her decision not to certify. “And in my duty as a board member, I want to make sure that happens.”

Adams did not return a request for comment. An attorney for the America First Policy Institute, Mike Berry, told the Guardian in an email that its their policy that clients may not speak to the media in the absence of their attorney.

“This lawsuit simply seeks resolution of the issue of whether Fulton county can delegate [board of registration and election] member duties to an unelected bureaucrat, and whether BRE member duties are merely a rubber stamp,” Berry said. “Ms Adams seeks to perform her statutorily defined duties and she cannot do so until these issues are resolved.”

Berry did not respond to questions about Adams role with the Election Integrity Network.

Georgia’s Democratic party and the Democratic National Committee are intervening in the case. The Democratic congresswoman Nikema Williams, who represents Atlanta, said Adams’ suit is part of a broader plan to aid Trump in a potential effort to cast doubt on the November election if he doesn’t win Georgia.

“This is a transparent attempt to set the stage for that fight,” Williams said of Adams’ lawsuit. “The Democratic party of Georgia will continue to combat Trump’s efforts to undermine our democracy and ensure local elections are certified, which is required by law.”

County elections staff had been preparing for Adams’ objections to the 21 May primary, meticulously laying out stacks of election documentation at a board meeting on 28 May. Some of the documents were presented on laptops. Adams asked why they could not have been emailed to her, as she requested. The files were too large to email and too cumbersome to print, replied Nadine Williams, Fulton county’s elections director.

“It would take us over 10,000 pages to print these things,” Williams said.

After spending nearly seven hours paging through pages of voter lists, poll pad reports, tape results, memory card chain of custody reports and other documents, Adams asked for additional material – which elections administrators provided – before abstaining from the vote to certify.