Resistance Report: The fight against the Dakota Access pipeline came to Washington with the Native Nations Rise march

WASHINGTON — They came from across the United States, and from as far away as Mexico and Canada.

Comanche, Apache, Navajo, Pueblo, and Sioux; Cree, Ojibwe, Chippewa, Aztec and California tribal nations were all represented.

Miss Standing Rock H.S., in braces and pale blue beaded moccasins, led the march along with other Standing Rock Sioux youth who had been a critical part of the movement against the Dakota Access pipeline. They started outside the D.C. offices of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which announced on Feb. 8 that with President Trump’s executive order smoothing the way, it will grant an easement to Energy Transfer Partners to build the final leg of the Dakota Access pipeline. The 1,172-mile crude oil pipeline will run underground half a mile from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, passing under Army Corps-owned land around the narrowest part of Lake Oahe in North Dakota, a dam-created reservoir of the Missouri River.

Numbering thousands strong, many protesters had been part of the Oceti Sakowin Camp of “water protectors” at Standing Rock before the camp was forcibly disbanded in February. Some had been involved with the fight since last April; others were newer to the movement. There was a substantial Pueblo Indian presence, a reflection of the February declaration by all 23 registered tribes in New Mexico that they stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux in opposing the project. New Mexico has the second-highest percentage of Native American residents of any state after Alaska, and tribes in New Mexico are gearing up to fight the Bureau of Land Management’s decision in January to allow fracking near Chaco Canyon’s fragile archeological sites and 1,000-year-old Pueblo ruins.

They chanted, “We can’t drink oil — Water is life!” and “Honor the treaties! Water is life!” and “Day by day, block by block, we will stand with Standing Rock!” They ululated and drummed and sang. A group of men brought tepee poles and erected a structure with swift, sure movements outside the Trump Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, where women in long skirts sewn at the encampment did a round dance about its circumference while a blond woman looked down from a hotel window. A cardboard cutout of Trump was tossed to the ground, and men and women thrust their beribboned poles onto it, smudging the cardboard surface. An Apache woman sported a giant, red Make America Great Again cap, with two mock arrows piercing it.

“Standing Rock, this monument, marks the turning point of history. It’s not only for our tribe, but for all tribes, and for America as well. Because the heart of our movement is now the heart of the resistance,” Dave Archambault II, chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, said at Lafayette Park after the marchers reached the White House.

“You know, we face a lot of obstacles and we face a lot of setbacks,” Archambault said. “But we’re not defeated. We’re not defeated. And we’re not going to be the victims. An obstacle is also an opportunity. Together, all of us, we can confront these obstacles. And we can look at these opportunities and embrace them. So together we can rise.”

“Many communities are now experiencing what we have experienced for centuries,” he added, tying the Standing Rock fight to the Trump administration’s treatment of minorities and immigrants. “Instead of striving for mutual beneficial outcomes through understanding, the new administration dictates. Instead of expanding human rights, the new administration limits human rights. Instead of inspiring, the new administration manipulates. Treaties are signed with Native American tribes, but when these treaties become inconvenient, these treaties are ignored and they’re broken. Laws that provide freedom and equal rights were also put in place for all Americans. Yet each week we see more basic human rights threatened by a distant and disengaged administration. For all American citizens today, both Native American and non-Native America, ask the question, ‘Why?’ What can possibly justify the dismissal of basic human respect?”

Yahoo News spoke with some of the attendees at the march about why they were there and what it meant for the indigenous rights movement that has gained strength through the fight over the Dakota Access pipeline.

“It’s about more than [the Dakota Access pipeline]. It’s about indigenous rights,” said Jody Gaskin, an Ojibwe from Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., who was marching with his son, Dakota Sky. “It’s about protecting the earth for our grandkids. Pipelines are just one part of it. But it’s a big part of it, you know. But it’s the pipeline that brought us together. It’s pretty cool, I think. Brought us all together like this. It’s pretty awesome.”

What happens next, then?

“We go home. Be active, take this energy back to our families,” he said. “Keep talking about it. So they’ll pick up the torch when we put it down or it’s time for us to move on. Just keeping it alive, keeping the movement alive. And it’s not even a Native thing, it’s a human thing. It’s about all of our children. What are you going to do when your grandkids come and say why didn’t you do something, you knew they were polluting the water? Why didn’t you do something, you know. So today is a chance for us to do something.”

Lorraine Shooter, 39, from Standing Rock, S.D., and Leann Eastman, from Sisseton on the Lake Traverse Reservation in S.D., wore skirts with ribbons on them, a style also worn by many of the other marchers. They are “Dakota water dresses,” Eastman explained. “For every ribbon, there’s a prayer.” The dresses, designed by her, were made at Standing Rock Camp.

Kristina Elote, 26, from Dulce, N.M., and the Jicarilla Apache Nation, wore a Trump-branded prop hat. She helped start the International Indigenous Youth Council at the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock.

When I asked Marcos Aguilar, with an Aztec dance group from Los Angeles by way of Mexico City, if the coming together of tribes seen in the march was unusual, he raised an important point about the relationship between indigenous people’s lack of control over land in the Americas and the current immigration issues in the United States.

“Unusual? Yes,” he said. “It’s not often that indigenous peoples have to suffer water cannons, 800 arrests, militarized evacuations, in order to call attention to basic human rights in the United States. Things that should have been taken for granted can no longer be taken for granted. So yes, it’s unusual for tens of thousands of native people to have to gather to call upon this country to live by its treaty rights, its treaty obligations, and also to respect the rights of indigenous people across the continent, which through its policies, economic and political, have been forced into patterns of migration or refugee status from Central America and South America now living in the United States.

“And this is all connected. Everything that happened in Standing Rock has happened in Mexico. Over and over. It’s happened in Guatemala. Over and over. It’s happened in El Salvador. Over and over. It’s happened in South America. The same moneyed interest, the same capital interests, behind those powers. So we’re calling for an end, but more than that we’re calling on ourselves for the self-recognition of our autonomy and our own sovereignty. We need to stand on our own two feet.”

“We’re out to support all the indigenous tribes. I didn’t believe there was going to be this many people here,” said Michaela Alire, 51, from Towaoc on the Ute Reservation in Southwest Colorado. “It’s good to see people come from all over, all different types of people. Not just indigenous people.”

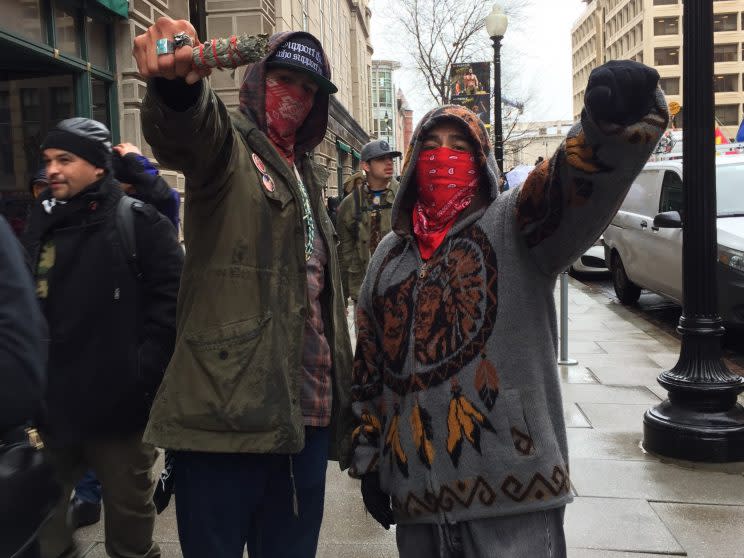

Not everyone wanted to be known. “It’s a representation of who I am, me and myself, wearing my colors. Proud to be red. Red Power. It’s who I am,” said Leroy, 33, from California, of the red bandana he wore. He and his friend Eddie, 45, both declined to give last names.