The RFK Jr. Experience

AURORA, Colorado—About an hour before a campaign rally for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. would get underway here on a bright Sunday afternoon in late May, fly-on-the-wall conversations offered a window into the world of the cultish independent presidential contender from the famous Democratic family.

There are two men trying to make sense of actress “Sandy” Bullock’s love life. Her ex-husband is such an “ass—” one says, wondering how the Oscar winner married him in the first place. It’s not the usual political rally pre-conversation, but it’s an example of the Hollywood-infused Kennedy campaign. Other super-Kennedy-supporters who’ve arrived early exchange comments about “medical freedom” and how mainstream doctors and Western medicine kills people.

Vaccines? The media, still others say, is out to get Kennedy, trying to weaponize his opposition to immunizations to paint him as an unacceptable weirdo.

“California is turning into a communist state and it got me sick,” declares one woman to her conversation partner before the rally gets started inside an airy factory-turned-food-hall in suburban Denver. Soured on California in part because of coronavirus vaccine mandates, the woman explains that she’s packing up and moving to Nashville.

The small groups milling about before the rally eventually grew into a standing-room-only thicket of approximately 1,500 that filed into the venue after passing through a security checkpoint. The room filled up such that the Kennedy campaign was forced, last minute, to create an outside overflow space. That’s not inconsequential. Kennedy, demonstrating an ability to attract a crowd and coalesce committed voters behind his longshot candidacy, may never threaten victory. But he could build a movement big enough to knock off one of the two White House frontrunners: President Joe Biden and presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump.

Those shuffling in included a mixture of Kennedy friends and fans from California and elsewhere supporting his underdog White House bid and otherwise enjoy the show; voters opposed to vaccine mandates, including for school age children and for diseases like measles and polio (not just COVID-19); voters who don’t like Trump any more than they like Biden and crave an authentic political outsider; and voters who, every four years, spurn the Democratic and Republican nominees in favor of hopeless third-party gadflies.

Regardless of their personal background, political motivations, age, or gender, they were bound together by their saintly reverence for Kennedy, the 70-year-old environmental lawyer and anti-vaccine activist whose family tree has produced a president, a U.S. senator, and a U.S. attorney general-turned-U.S. senator (his father, Robert F. Kennedy).

To a person, voters The Dispatch spoke with assessed Kennedy the younger to be unfailingly courageous and honest, a breath of fresh air in a campaign featuring two major party candidates whom a majority of voters claim not to want. And they all expressed confidence he can win—despite the fact that he has yet to qualify for ballots in enough states to compete for the requisite 270 Electoral College votes, and that it remains unclear he ever will.

“I love this man. He speaks the truth” said Alan Ingraham, 62, a retired firefighter from metropolitan Denver who voted for neither Biden nor Trump in 2020. “I just pick up from him that he’s telling the truth and he really cares about people.”

“I love this man. I think he’s an honorable person,” added Brigette Bustos, 46, a global communications executive from the Denver area who twice voted for Trump and has not ruled out doing so a third time despite her adoration of Kennedy. “I think America needs him. I’m just not sure that Washington deserves him.”

Kennedy himself may be on the quirky side, but his campaign rally was the picture of detailed staging and orderly advance work.

The campaign scheduled the “voter rally” in greater Denver as part of a major push to collect enough signatures to get “Bobby on the ballot” in Colorado, a state that seemingly turns a deeper hue of blue with every election since President George W. Bush won here in 2004. To date, the Kennedy campaign claims to have submitted the “necessary signatures” to obtain ballot lines in eight states worth 138 electoral votes: California, Delaware, Hawaii, Michigan, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas and Utah.

To add Colorado to that list, campaign volunteers in Kennedy 2024 T-shirts and other garb cheerfully milled about Stanley Marketplace canvassing for signatures for more than an hour before the scheduled 3 p.m. kickoff and continued the petition drive long after the rally began.

“All right guys, we’re opening the doors!” a campaign aid bellowed inside the event space just before go-time.

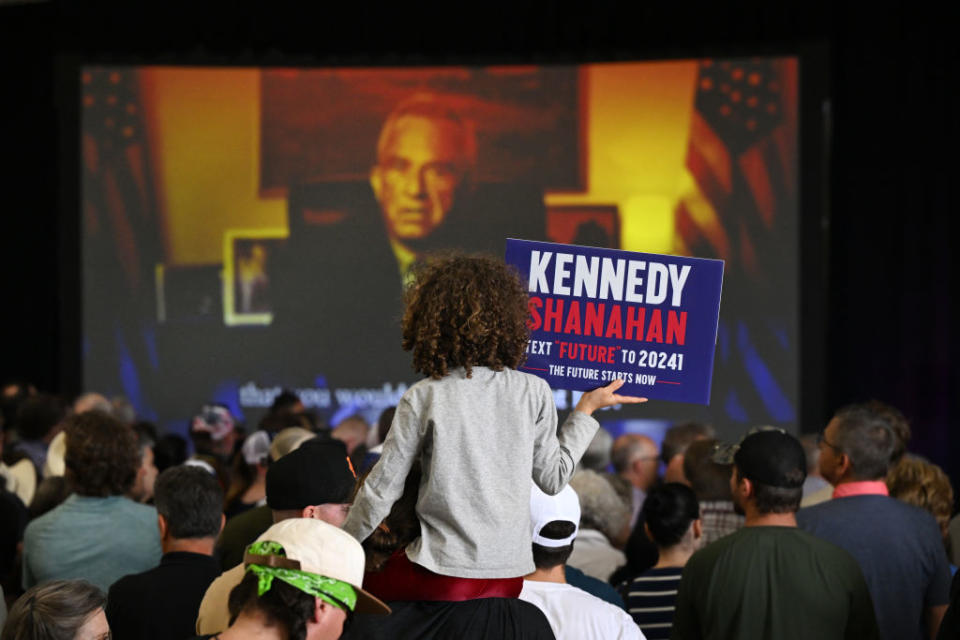

But the rally would be delayed almost an hour: A long, single-file line of rallygoers snaked to the opposite end of the food hall, in part because of strict security protocols. When they made it inside, they found staff handing out stacks of red, white, and blue “Kennedy Shanahan” signs, which made for a good visual for a clip in an upcoming campaign video. The “Shanahan” in the sign is Nicole Shanahan, Kennedy’s 38-year-old running mate. She’s a successful lawyer who collected a financial windfall as part of the settlement in her 2022 divorce from Google co-founder Sergey Brin.

In back was plenty of Kennedy campaign swag, including baseball caps, snow hats, T-shirts, and tote bags in a wide range of colors. Up front were two massive, rectangular screens that read: “Kennedy Shanhan; People Before Politics, Country Before Party.” To warm up the crowd, the screens intermittently played glossy campaign videos that leaned heavily on Kennedy family nostalgia.

Featured just as much, if not more, than Kennedy the 2024 candidate were old reels of his uncle, President John F. Kennedy, assassinated in Dallas in November 1963. And of his father, RFK, the frontrunner for Democratic presidential nomination in June 1968 when he was shot dead by Palestinian terrorist Sirhan Sirhan because of his support for Israel.

A three-piece rock cover band belted out sentimental hits like Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” and Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.” It was a solid performance, but completely unnecessary: Members of the crowd were already jovial, chit-chatting with each other and taking selfies to commemorate the moment.

Public opinion polls suggest Kennedy is poised to undercut Biden more than Trump if he can get on the ballot in enough states to legitimately compete for the White House. In a head-to-head, the former president leads the current president 46.3 percent to 45.5 percent, a margin of 0.7 percentage points, in the RealClearPolitics average of national surveys. Trump’s lead grows to 1.9 points (41.4 percent to 39.5 percent) in a five-way matchup that includes Kennedy, fellow independent contender Cornel West, and Green Party nominee Jill Stein.

Kennedy, who briefly challenged Biden for the Democratic Party’s 2024 nomination before shifting to an independent bid, is garnering 10.4 percent in the five-way average but is doing better than that in some individual national polls and battleground state surveys.

However Kennedy ends up affecting the 2024 campaign (if at all) conversations with supporters who showed up to see him in Aurora revealed that the independent candidate is attracting Americans from across the political spectrum. The Dispatch interviewed voters who lean left and backed Biden in 2020; voters who lean right and pulled the lever for Trump in 2016 and 2020; and those who voted in the two most recent presidential elections but checked the box for neither the Democratic nor Republican nominees, as is their habit.

The crowd was a collection of individualists who, in an earlier era, might have been called “hippies.”

Although mostly (but not totally) white, it was diverse in other ways. Some were young, some were old, and some were middle-aged. There was a mixture of Hollywood chic—many fashionably tattooed and others stylishly dressed (hat tip to the slender woman in silver, sequined bell bottoms). There were middle class couples from the Denver exurbs, casually attired, many with kids in tow. By the numbers, the political and racial makeup of the Kennedy coalition, such that it is, is unclear, because the data is scant.

But in one recent poll, Kennedy was drawing slightly more self-identified Democrats than Republicans, with more backing from self-identified independents than voters who claimed to affiliate with either of the two major parties. In another poll, Kennedy’s support among black voters and white voters was roughly equal, with his backing among Hispanic voters slightly higher. But his support in this survey was so minimal—low single digits—that it’s impossible to arrive at any conclusions about Kennedy’s potential or what the existing data really means.

For Hank, a 36-year-old farmer from northern New Mexico who declined to provide his last name, support for Kennedy is all about “soil health.” That focus, said Hank, who wore boots, jeans, a western-style button-down shirt, and a cowboy hat, is “going to make us a [much] stronger nation, by making sure our food is actually nutritious.”

“He’s been genuine, I think, for our Mother Earth,” he added. “That’s very important. We can’t live, we can’t argue, we can’t enjoy the good times, if we’re not all healthy and he’s the only one talking about that very important issue, it all starts back at our food security, food web and of course, that all starts in the soil.” After voting for Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson in 2016, Hank supported Trump in 2020.

A scan of the, let’s say, more colorful campaign paraphernalia worn by rallygoers included a T-shirt that read “F— Trump,” a baseball cap with the message “End DEI,” and what looked like a homemade button that said “Proudly Vegan and Covid UNvaccinated.” But whether liberal, conservative, or iconoclast, they all shared a kind of messianic faith in Kennedy’s ability to cure the myriad ills they are convinced are ailing American society—both medically and psychologically.

“He’s bringing positive changes,” said Susan Wittmann, 70, a Kennedy volunteer who lives near Boulder. She voted for Biden in 2020 and Hillary Clinton in 2016. Her top issue, as with many Kennedy acolytes, is “health freedom.” “My body, my choice,” she said. “I don’t believe the government should tell me what to do with my body.” That’s Wittmann’s view on abortion—and vaccine mandates.

When Kennedy finally arrived on stage, he received a hero’s welcome. “Bobby, Bobby, Bobby!” the crowd chanted. It was well past the time Kennedy was scheduled to appear on stage, but almost nobody had left.

Before the star of the show would deliver a 50-minute stemwinder, his underlings offered stump speeches of their own, unusual since campaign aides and advisers are typically background players who fill time when needed before the candidate speaks. But at Kennedy’s rally, key staff and advisers were featured in supporting roles and nearly stole the show.

Even as their remarks lionized the principal and promoted an agenda centered around suspicion of, and opposition to, western medicine broadly and vaccines specifically, they spent a good deal of time talking about themselves.

There was Robyn Ross, quoted in a December Washington Post story as the campaign’s research director but who introduced herself as the general counsel. She recalled her journey from general counsel of Stanley Marketplace, when the development of the food hall was in its infancy, to a top Kennedy campaign aide. Her dream all those years ago, she said, was to be Kennedy’s speechwriter. “Look at me now,” Ross said. “I’m not the speechwriter—he gave that job to somebody else. But I get to be the lawyer.”

There was senior adviser Theo Wilson, who opened his remarks with “greetings as a proud former member of the Democratic Party,” which is dominated by the “donor class” and “pharmaceutical lackeys.” The Kennedy campaign, on the other hand, would be a “retribution of the people” against the corporations that “control our government,” said Wilson, who is black. And regarding the coronavirus vaccine: “As the descendant of those who were enslaved, I have the right to say: ‘I am not for any kind of jab-Jim Crow action.’”

Then there was communications director Del Bigtree, who appeared to receive just as big of a reaction from the crowd as did Kennedy. Bigtree, a television producer by trade, talked Kennedy up by highlighting his physical prowess (not unlike a certain other presidential campaign), such as when Kennedy cruised down ski slopes at nearly 60 mph. “Swear to God,” Bigtree declared. “Think about that—a president that can do, I don’t know, what’s it? Twenty-five, 30 pullups? … Can catch a wave, anywhere in the ocean? Or, we can have people who can barely walk, or eat McDonald’s all day, every day.”

Kennedy was practically subdued compared to his warm-up acts. Clad in a silver suit, white dress shirt and dark, narrow tie—itself a throwback to the 1950s and 1960s of his family’s political heyday—the former lifelong Democrat, in his distinct, gravely voice, presented as a mild-mannered version of Trump.

There were comparisons of his physical stamina to Biden’s, claims of election rigging and media bias, allegations of Biden and Trump colluding to keep him off the debate stage, claims of manipulated polls, complaints about big business and a s0-called “war machine” conniving with Washington to rip off honest, patriotic Americans.

And there were warnings about political polarization that Kennedy catastrophized is setting the stage for a second civil war.

The White House hopeful did not exactly say “I alone can fix it.” But he sort of did. “If I get elected, everything’s going to change.”