Rooming houses were once plentiful and cheap housing. Now, in RI, they're a dying breed.

WOONSOCKET — Long before Russell Archambault was born, his mother needed to escape her first marriage.

Desperate to leave her drunken husband, she wound up in a rooming house on Social Street. It was a disgusting place, infested with bedbugs and rats, she’d later tell her son.

“That always took me a little bit, how she had to live,” recalled Archambault.

Rooming houses – where tenants rent a single furnished room with no kitchen and share a bathroom – have a reputation for squalid living conditions, but they are often a refuge people with nowhere else to go. Also known as boarding houses or single-room occupancy hotels (SROs), they’re one of the cheapest forms of housing on the market.

They’re also increasingly hard to find. Woonsocket, which had 19 licensed rooming houses in 1964, is down to just four today. Pawtucket had 55 rooming houses in 1960, but there were just 15 by 1980, and city officials say they’re not aware of any in business today.

Nationwide, the number of rooming house residents shrank from 634,000 in 1960 to 330,000 a decade later. Today, the U.S. Census Bureau doesn’t track that figure at all.

Few policymakers have lamented, let alone remarked on, their slow disappearance – even as Rhode Island faces a statewide shortage of affordable housing and a steep rise in homelessness. That doesn’t surprise Archambault, who owns two of Woonsocket’s last remaining rooming houses and says that his mother’s experience inspired him to provide safe, clean and decent accommodations for low-income tenants.

“People have the perception that rooming houses are just for drunks, drug addicts and worthless people,” said Archambault, now 71. He takes issue with those assumptions: “I could take you to every room, and they’re all good, good people. There’s nothing worse with them than me.”

‘It’s comfortable here’: Life inside a Woonsocket rooming house

Ed LeBlanc lives in a small but impeccably tidy first-floor room at 233 High St., where a microwave and toaster oven sit a few feet away from his recliner and neatly made bed. Cacti, pothos and snake plants – many of which he nursed back to life after they were left behind by other tenants – line glass shelves in front of the single window.

Before moving into the rooming house four years ago, he said, he mainly slept in his car or on the dirt floor of a friend’s basement. Now he helps to manage the building.

“It’s comfortable here, very comfortable,” he said. “You just have to adapt.”

The lifestyle isn’t exactly glamorous. Tenants carry their own toilet paper and soap on trips to the bathroom. But rooms are equipped with mattresses that typically retail for $1,500, new GE compact refrigerators, and matching secondhand furniture, Archambault said as he showed a reporter around on a quiet winter afternoon.

Free Wi-Fi and cable are included with the rent, and he often provides TVs for his tenants. He maintains a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to drug use, and also bans potential fire hazards such as extension cords. A cleaner comes at least five times a week to scrub the common areas.

Archambault purchased 233 High St., which has 30 rooms, and 154 Pond St., which has 26, in the 1980s. He says he’s devoted his life to improving them – from installing fire-safe hardware to cracking down on problem tenants.

In fact, Archambault even lives in one of his own rooming houses: In 2014, after a woman with whom he’d been in a long-term relationship became seriously ill, he moved into 233 High St. It was a decision prompted by turmoil in his personal life, he said, as well as a desire to see what rooming house life was really like.

“There's not a better place to live,” he says now.

A cost-effective option from an earlier era

Rooming houses didn’t always carry a stigma. They began popping up toward the end of the 19th century, in an era when it was already common for city-dwellers to move into strangers’ homes as paying lodgers and sometimes even continue to live there after getting married and starting families of their own.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, men and women began flocking to urban areas, filling the growing number of blue- and white-collar jobs in factories and offices. Rooming houses and residential hotels offered them basic, affordable accommodations, historian Paul Groth would later document in “Living Downtown,” which traces the rise and fall of the phenomenon.

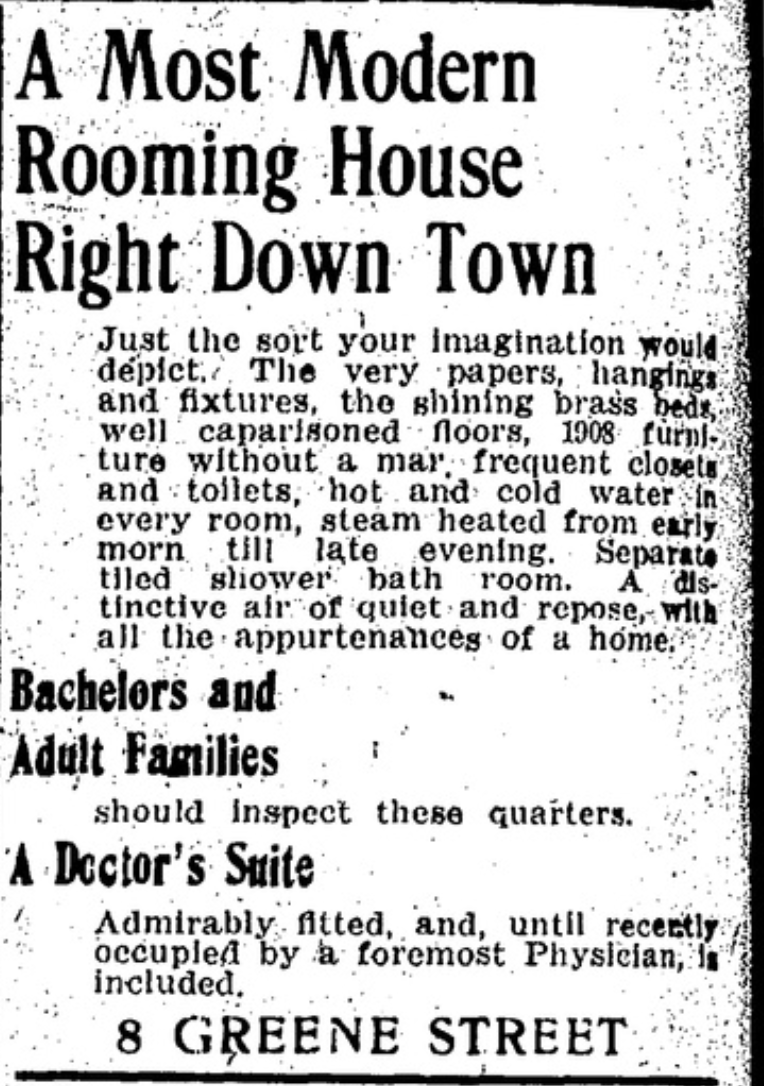

“A distinctive air of quiet and repose, with all the appurtenances of a home,” promised a 1908 ad in The Providence Journal for “A Most Modern Rooming House Right Downtown.” Aimed at “bachelors and adult families,” it touted amenities such as steam heat, “shining brass beds” and brand-new furniture “without a mar.”

By 1919, the Providence City Directory listed two full pages of boarding and rooming houses. Some were dirty, violent flophouses run by slumlords, newspaper accounts from the time indicate. But most provided respectable homes for young people striking out on their own, or professionals moving to a new city in search of work.

Today, rooming houses can still be the most convenient, cost-effective option for people whose careers bring them to an unfamiliar city. Archambault said he’s rented rooms to traveling nurse, and, once, a Hungarian doctor.

Most tenants, though, are locals who hold lower-wage jobs: There’s an Uber driver, a forklift operator, waitresses, gas station attendants and people who work at Walmart, Burlington, Burger King, Family Dollar and Stop & Shop.

In the past, Archambault said, most rooming house residents relied on Supplemental Security Income. Now, it’s common for him to rent to people who work full-time but can’t afford a place of their own.

Some tenants temporarily land at his rooming houses while they’re getting divorced or struggling financially. Others, especially those on a fixed income, are looking for a place to live out the rest of their lives.

“Sometimes it’s just a steppingstone,” LeBlanc said. “They’ll come here for a few months, get things situated, and then they can move on. And in some cases they don’t. For instance, me. I’m not moving out.”

What is it like to live in a rooming house? Cheap rent but strict rules

According to HousingWorks RI’s factbook, the average two-bedroom apartment in Woonsocket now rents for $1,403 a month

Archambault charges only about half that amount: New tenants pay $650 a month, or $150 a week, plus an additional $100 deposit when they move in. Utilities are included, aside from air conditioning, which costs an additional $15 per week (or $50 per month) in summer.

His long-term tenants pay even less than that, he said, since he tries not to raise rents for existing tenants.

Demand is high enough that Archambault doesn’t need to do much advertising – at most, he posts on Craigslist once or twice a year. Often, he said, he gets referrals from social service agencies such as Community Care Alliance.

Tenants tend to be single; Archambault says he’s had bad experiences renting to couples. No overnight guests are allowed, and LeBlanc patrols the building at night to make sure that no one’s breaking the rules.

Archambault says he conducts background checks on all tenants, but a criminal record isn’t necessarily a deal breaker. “I’ll rent to anybody that is honest with me,” he said.

Sex offenders sometimes live in his buildings, “and, you know what, they are the best tenants, because they stay clean and they keep to themselves.”

Plenty of people who walk the halls have complicated pasts, or appear to be alone in the world. Some stay for decades – quietly paying their rent, revealing little, and eventually dying in their rooms.

Often, Archambault said, that’s when their relatives finally come out of the woodwork.

“I had a guy – 15 years he was alone, never got a visitor,” he recalled. “When he died, I found out he was related to the lady across the street at the laundromat. He was a veteran. Nicest man in the world. He had no one. Everyone abandoned him.”

What happened to all the SROs?

Even at the peak of their popularity, rooming houses drew suspicion from progressive crusaders, who viewed them as unacceptably crowded, likely to spread disease, conducive to immoral behavior and responsible for declining birth rates.

But the push to eradicate them began in earnest in the 1950s as part of an urban renewal movement that sought to eliminate poverty by getting rid of the places where poor people lived.

More: Rhode Island's housing crisis is at a breaking point. How did we get here?

Rooming houses, though not yet exclusively inhabited by the down and out, were considered a form of blight and a threat to property values. The American Planning Association summed up the prevailing sentiment in a 1957 report, labeling them as “both symptoms and causes of neighborhood decay.”

In Providence, about 400 people were displaced from rooming houses in the Hayward Park neighborhood that were torn down to make room for Interstate 95 in the early 1960s. Many were elderly and had been paying $4 to $8 a month in rent. Another slum clearance project led to the demolition of an additional 50 rooming houses between Westminster, Broad and Bridgham streets.

Urban reformers had valid concerns about living conditions inside rooming houses, which could quickly become firetraps. In 1964, after three men were killed in a Woonsocket blaze, the city’s chief housing inspector determined that 17 out of 19 licensed rooming houses weren’t meeting minimum safety standards.

The problem was that once derelict rooming houses were demolished, nothing better came along to replace them. New public housing complexes were constructed, but they didn’t have enough room for everyone who’d been forced to move in the name of urban renewal.

The end result, The Providence Journal reported in 1973, was that people wound up in neighborhoods “almost as rundown as the slum they left” – while paying considerably more rent.

Zoning and gentrification took a toll

By then, municipal leaders in the state’s urban core had not only bulldozed dozens of rooming houses but also enacted zoning ordinances that effectively outlawed new ones.

Even though tenants routinely lacked cars, some communities made rooming houses subject to off-street parking requirements. Others changed their zoning ordinances so that converting large, impractical Victorian mansions into rooming houses would no longer be allowed by right.

In Providence, for instance, many of the houses lining the northern end of Benefit Street had been divided up into cheap single rooms. But by 1966, preservationists were starting to purchase historic homes in the neighborhood, and spending considerable sums to restore them.

To prevent the further spread of rooming houses, groups like the Providence Preservation Society lobbied the city to impose two-family zoning in the neighborhood. Later, Fox Point residents would push for the same changes.

“We believe rooming houses have held back development of the area,” Bayard Wharton, the president of Benefit Street Association, explained at one crowded public hearing. Other residents piled on, claiming that rooming houses were rife with narcotics and “loose and immoral” young adults.

Housing in RI: Triple-deckers were efficient housing for generations. Why did we stop building them?

Gentrification also took a toll in other ways. In desirable areas, rooming houses were snapped up by investors eager to turn them back into single-family homes, or transform them into offices for lawyers and doctors. Between 1975 and 1987, as Newport transitioned from a Navy town to a tourist destination, the city went from having more than a dozen rooming houses to just one.

In less desirable areas, meanwhile, some rooming houses became open markets for drugs and prostitution. Others, neglected by absentee landlords, fell into severe disrepair. There were suspicious fires, as well as others that were all too predictable – sparked by smoldering cigarettes, unsafe wiring or illegal cooking equipment.

Societal standards had shifted: In 1908, a private bathroom in an apartment was a luxury, but by 1988 it was expected. No longer attractive to most young professionals, rooming houses instead catered to the poorest of the poor.

“Most rooming-house residents have small incomes and are attracted by the low rents,” The Providence Journal observed in 1980. “Many are elderly. And many of the residents live alone – often with illness or alcoholism.”

Landlords cast into an unwanted role

The mass deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients in the 1960s and 1970s also had a dramatic impact on rooming houses. As Groth writes in “Living Downtown,” thousands of people were “essentially dumped” in SROs across the country, where no one was prepared to care for them.

With so many residents at the end of their rope or dealing with untreated mental illnesses, life in a rooming house could be dangerous. Simmering frustrations over something like the volume of a neighbor’s television were, in some instances, enough to provoke a violent attack.

Robert Lussier, who owns a rooming house on Hamlet Avenue in Woonsocket, says that he’s about ready to retire. One of the problems with running a rooming house, in his view, is that he can’t screen potential tenants for mental health issues.

“You’ve got people on medications that you cannot ask them about,” he said. “And then they come in, and they go crazy.”

Tenants like those need social workers and support services – and there are nonprofit SROs, such as those operated by Crossroads Rhode Island, where that kind of help is available.

Traditional rooming houses, however, were never intended to fill that role. And most landlords simply aren’t equipped to deal with tenants who are in the midst of mental health crises, or struggling with addiction.

“Managing people is the key. And caring,” Archambault said. “But it doesn’t take much to care for somebody. It just doesn’t.”

At the same, Archambault is quick to evict tenants who are noisy, messy or disruptive, in the interest of preventing conflicts. And after purchasing the Pond Street property in 1985, he went to extreme lengths to get rid of undesirable tenants, using tactics that he admits wouldn’t fly today.

When one woman with a severe drinking problem routinely failed to pay the rent, he removed the door to her room, only to return and find that she had hung a curtain in its place. It was only after he cut a hole in her wall in the middle of winter that she finally left, he said.

Another tenant, known as “Tex,” was a painter and talented pool player who drank a six-pack every day – “and that’s after he got back from the Shamrock Cafe,” Archambault recalled.

Tex “had a pocketful of money all the time,” but he always had to be chased down for the rent. One day, Archambault found himself pounding on Tex’s door again and got fed up. He cut a hole in the door with a reciprocating saw, then reached through and undid the lock.

Acting like nothing had happened, Tex greeted him warmly – “Hey Russ, come on in. How you doing?” – and handed over the rent.

“So I fell in love with him after that,” Archambault said.

Later, Tex moved into the rooming house on High Street and lived there for about a decade before he died.

“I took care of him at the end,” Archambault said. “It was quite a thing – he left me his pool stick.”

Rhode Island’s remaining rooming houses are a dying breed

Woonsocket, along with West Warwick, is one of the few places in Rhode Island where you can find old-fashioned rooming houses today. Many are still run by so-called “mom and pop” landlords, though others are now owned by opaque limited liability corporations.

Over the years, Archambault has watched the numbers shrink. In some cases, the elderly people who owned them passed away and their families weren’t interested in taking over, he said. In other cases, landlords simply couldn’t keep up with tightening regulations.

Under state law, all rooming houses need to be licensed. That means they’re subject to annual fire inspections – sprinklers need to be in every room, and even the bathrooms have to be equipped with loud fire alarms – as well as code inspections conducted by city officials.

“It’s almost like buying a boat – break out another thousand every time they come,” said Lussier, who’s been in the business for decades,

After The Station nightclub fire in 2003, officials became much stricter about enforcing the fire code, Archambault said. That required rooming house owners to make some costly upgrades – which, in his view, was a good thing.

“Everything is regulated for the tenant to be safe, which I agree with,” he said. Just last year, he pointed out, a “lousy little extension cord fire” at a four-story rooming house in New Bedford killed two people.

Occasionally, local authorities stumble upon illegal, unlicensed rooming houses – which are especially dangerous, since they aren’t undergoing fire safety inspections at all.

Last year, for instance, the Times-Gazette reported that officials in Warren had condemned a single-family home where some tenants were paying $135 a week to rent a bedroom with a padlock on the door, while others slept in a squalid basement filled with trash.

More: RI's melting pot: 100 years of shifting demographics through one street's history

It’s hard to know how many other examples are out there. Rather than disappearing, rooming houses may have simply moved underground.

In Archambault’s view, the state needs more legal, regulated rooming houses – not fewer. But he’s also the first to admit that he’s hardly the typical landlord.

After salvaging barbecue grills, wrought iron furniture and a birdbath from the scrapyard, he recently created a private courtyard so that tenants would have a tranquil place to spend time outside. Metal salvaged from a Woonsocket Napping Machine Corp. loom forms an arched entryway, while antique manhole covers and railroad wheels serve as pavers.

LeBlanc brings his coffee out there every day in warm weather, and he's trained squirrels to sit on him while he feeds them peanuts. Archambault, he said, “sees a lot of things that other people don't.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: RI rooming houses offer cheap rents and stability, if you can find one