How the runaway greenhouse gas effect can destroy a planet's habitability — including Earth's

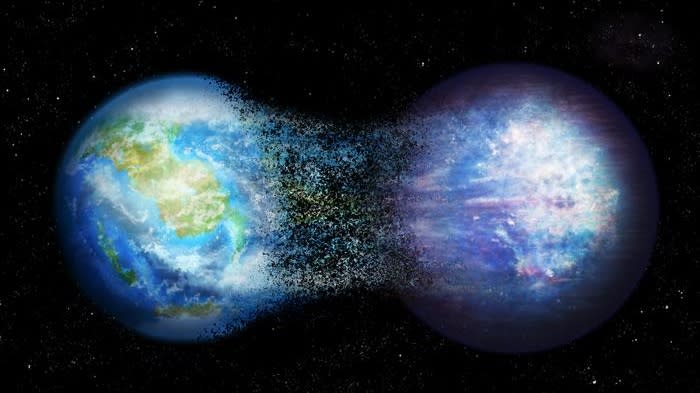

Using advanced computer simulations, scientists have shown how easily a runaway greenhouse effect can rapidly transform a habitable planet into a hellish world inhospitable to life.

Not only does this research have implications for our understanding of extrasolar planets, or "exoplanets," but it also offers insight into the human-driven climate crisis on Earth.

The team of astronomers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and CNRS laboratories of Paris and Bordeaux saw that after initial stages of a planet's climate transformation, the planet's atmosphere, structure and cloud coverage get significantly altered, such that a difficult-to-halt runaway effect starts to commence. Alarmingly, this process could be initiated here on Earth with just a slight change in solar luminosity or by a global average temperature rise of just a few tens of degrees. Even those minor changes could lead to our planet becoming totally inhospitable.

Thus, the research offers a stark climate change warning.

"Until now, other key studies in climatology have focused solely on either the temperate state before the runaway or either the inhabitable state post-runaway," Martin Turbet, CNRS scientist and team member, said in a statement. "It is the first time a team has studied the transition itself with a 3D global climate model, and has checked how the climate and the atmosphere evolve during that process."

Related: Tiny 14-inch satellite studies ‘hot Jupiter’ exoplanets evaporating into space

A critical greenhouse effect

The runaway greenhouse effect in the team's simulation can see a planet change from having a temperate, Earth-like hospitable state to one that exhibits a hellscape with surface temperatures of around 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius). That is hot enough to melt lead. These are temperatures even higher than those at the surface of Earth's famously hellish neighbor, Venus.

The cause of this runaway greenhouse effect is something very familiar: Water vapor — a major greenhouse gas. Though water vapor may not be the first greenhouse gas we think of when it comes to climate change on Earth, like more familiar greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, water vapor stops solar radiation absorbed by a planet's surface from escaping back to space. This traps heat around the world like a thermal blanket. Scientists call it the greenhouse effect.

In small doses, the greenhouse effect is useful; for instance, it stops Earth from exhibiting a temperature below the freezing point of water. But too much greenhouse-induced warming can force oceans to evaporate, putting much water vapor in the atmosphere. As you might imagine, that can cause even more greenhouse warming. It's like a feedback loop. Aha, the "runaway" greenhouse gas effect.

Venus actually provides a stark example of what can happen when a runaway greenhouse effect is kickstarted.

"There is a critical threshold for this amount of water vapor, beyond which the planet cannot cool down anymore," research leader and former University of Geneva Department of Astronomy scientist Guillaume Chaverot said. From there, everything gets carried away until the oceans end up getting fully evaporated and the temperature reaches several hundred degrees."

Warning clouds

One of the most important and surprising aspects coming out of the team's simulation was the development of an odd cloud pattern. This pattern didn’t just increase the runaway greenhouse effect but also made it irreversible.

"From the start of the transition, we can observe some very dense clouds developing in the high atmosphere," Chaverot said. "Actually, the latter does not display anymore the temperature inversion characteristic of the Earth's atmosphere and separates its two main layers: The troposphere and the stratosphere. The structure of the atmosphere is deeply altered."

As for what this means for us, with the results of the simulation in hand, the team calculated that it would take only a small increase in solar radiation and a rise in Earth's temperature of tens of degrees to trigger an apocalyptic runaway effect. If that happened, Earth would eventually become as hostile to life as its neighbor Venus presently is.

The news comes as countries attempt to limit human-driven greenhouse gases to cap Earth's overall warming to a quantity of 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050, showing how vital this effort really is.

The team isn't yet sure of the effect the release of greenhouse gases alone could have on the runaway process and whether that process can really just go "away" at the same temperatures. They also are yet to find whether an increase in solar luminosity could continue to drive the process.

"Assuming this runaway process would be started on Earth, an evaporation of only 10 meters of the oceans' surface would lead to a 1 bar increase of the atmospheric pressure at ground level," Chaverot said. "In just a few hundred years, we would reach a ground temperature of over 500 degrees Celsius. Later, we would even reach 273 bars of surface pressure and over 1,500 degrees Celsius, when all of the oceans would end up totally evaporated."

Related Stories:

— These scientists want to put a massive 'sunshade' in orbit to help fight climate change

— This ISS mission could 'open some eyes' about climate science

— NASA's new 'Greenhouse Gas Center' tracks humanity's contribution to climate change

The research is also deeply important as humanity becomes increasingly adept at spotting and studying planets around other stars, a scientific discipline that will eventually lead to us hunting for life outside the solar system.

"By studying the climate on other planets, one of our strongest motivations is to determine their potential to host life," team member and director of the University of Geneva Life in the Universe Center (LUC) émeline Bolmont said. "After the previous studies, we suspected already the existence of a water vapor threshold, but the appearance of this cloud pattern is a real surprise!"

The team’s research was published on Dec. 18 the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.