School shooting survivors united by a chain of grief — and hard lessons passed on

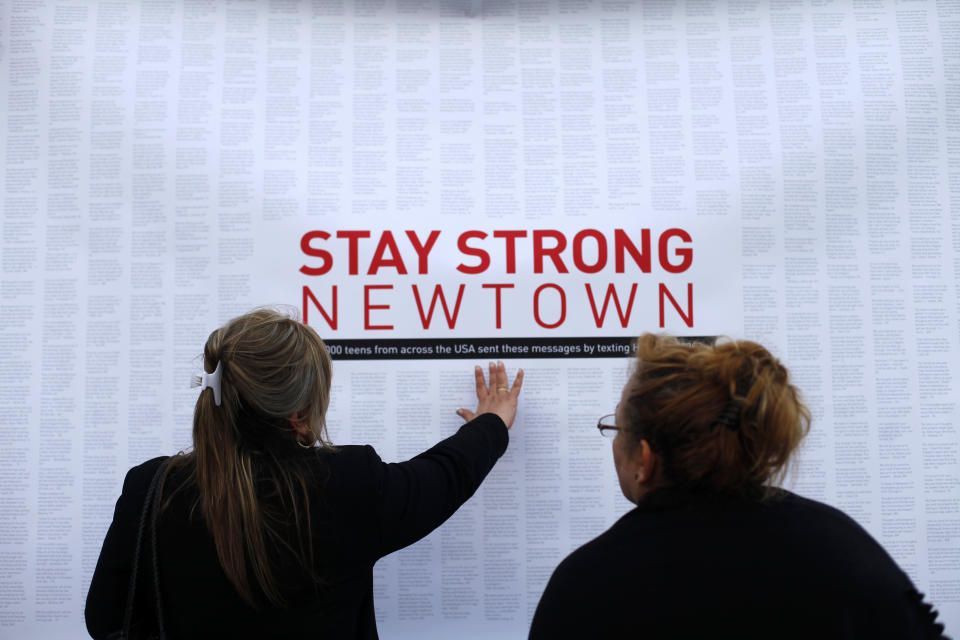

It was five years ago that a young man invaded Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., and shot and killed 20 young children and six staff members, a tragedy that indelibly scarred that small city and lives on in the collective national memory. But school shootings didn’t begin, or end, with Sandy Hook. Yahoo News looks at the aftermath of four of these tragedies and the lives they changed. In other stories, we examine how 20 years on, Jonesboro, Ark., is still traumatized by an attack carried out by two middle-school boys — and how survivors deal with the knowledge that the killers are now grown men and free from prison; at the lessons from Sandy Hook that may have helped save lives at a California school just last month; and at how the parents of a girl killed in Newtown are coping with their loss.

Holly Bailey, Dylan Stableford, Beth Greenfield and Jason Sickles contributed to this report.

_____

It happens soon after the shooting stops, often before the victims are buried and the crime tape is taken away, certainly while the parents and students and teachers are still numb, still reeling from their loss. Sometime during those raw, wrenching moments comes the first talk of healing.

“Faith, hope, love … healing,” read the banner at the memorial service in Jonesboro, Ark., for the five killed and 10 injured when an 11-year-old and a 13-year-old classmate pulled a fire alarm and picked off their victims as they marched out of their middle school in 1998.

“Healing Begins,” read the headline of the Denver Post the day after two students gunned down 14 classmates and a teacher, injuring 23 more, at Columbine High School in 1999. A month later, President Bill Clinton addressed thousands at a memorial service. “There has to be healing,” he said.

After 32 were killed and 23 were injured by a student on a rampage at Virginia Tech, President George W. Bush promised healing too. “Although it does not seem possible right now,” he said, “a day will come when Virginia Tech will return to normal.”

And hours after an intruder killed 20 first graders and staff members in Newtown, Conn., a school aide who’d witnessed the carnage told a television reporter: “We’re going to stick together and in time, we’re going to heal.”

Related slideshow: Images from Newtown >>>

Today is the fifth anniversary of that day, the fifth anniversary of that declaration. And the question thrumming beneath today’s memories and tributes is twofold: not just “Has Newtown healed?” but also “How does a community heal after this increasingly frequent kind of a loss?”

The roots of these questions are generations deep, back to a time well before Newtown, arguably before the American Revolution, when four Lenape tribe members entered the Enoch Brown schoolhouse in Pennsylvania in 1764, shooting and killing the schoolmaster, then murdering all but two of the children in the building.

And they are questions that stretch into the future, to a time well after Newtown, through the at least 104 times that shots have been fired at students and teachers since Dec. 14, 2012.

Finally, they are questions that ripple out beyond these communities, particularly as screens and cameras now bring the anguish to the nation as a whole, allowing strangers to mourn for, though not actually with, those who have suffered.

Related slideshow: Paducah, Jonesboro, Columbine and Newtown: A chain of tragedy and grief >>>

It’s not only schools where communities are ripped to shreds and left to knit the pieces back together. The lessons of the schools are also the lessons of the military bases at Fort Hood and the Washington Navy Yard, the movie theater in Aurora, Colo., the churches in Charleston, S.C., and Sutherland Springs, Texas, and the concert in Las Vegas.

But there is something singular and searing about the schools — an invasion of what is assumed to be a safe space, where the victims form a literal community, where families not only know each other, but also expect their lives to be entwined as their children grow.

And unlike many other kinds of spaces, school communities remain together, to nurse their collective wound, after the cameras have gone, after the politicians have gone to their ideological corners (“guns,” “mental health”) then departed, after the public has moved on, wearied by the seemingly constant march of death, and jaded by the gridlock and dysfunction that prevent any real change.

That’s when residents are left to figure out what healing means, and to navigate their way toward it. Their only real map is the cobbled-together wisdom of others who came before. It’s critically injured Jonesboro teacher Lynette Thetford receiving a letter from the mother of a girl who had been killed a few months earlier in a school shooting in West Paducah, Ky. It’s Columbine principal Frank DeAngelis getting a phone call from his Paducah counterpart, Bill Bond, who told him: “You don’t even know what you need right now. I was there. Take my number. When you need to talk, give me a call.” It’s Newtown helping Troutdale helping Marysville helping Roseburg helping Rancho Tehama helping Aztec. Together all these form a time-lapse of the healing process, each at a different point on a metaphorical journey, the totality of which extends across the nation and the decades.

Newtown is five years into this process. Have residents healed? If so, how? If not, when? And what lessons have they learned from others who’ve traveled the same increasingly familiar path?

_____

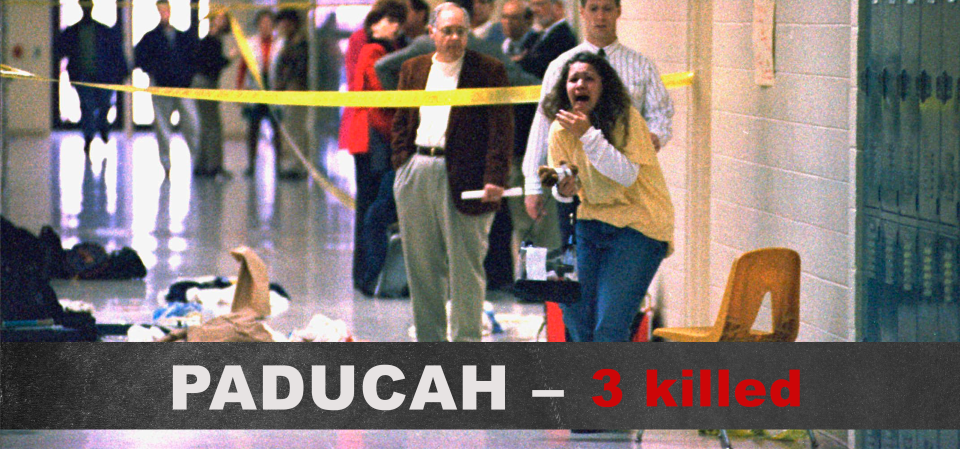

Just before 8 a.m. on Dec. 1, 1997, 14-year-old Michael Carneal walked into Heath High School in West Paducah, Ky., with several shotguns in his backpack. With a Ruger MK II .22-caliber pistol, he fired eight rounds at a group of classmates gathered in the lobby for the regular morning prayer circle. Three were killed. Five were wounded, one of them paralyzed by a bullet to the chest. Then, with one bullet still left in the chamber, Carneal put his weapon on the ground, slumped to the floor and told the approaching principal, Bill Bond: “Kill me, please kill me. I can’t believe I did that.”

With that, Paducah became the first name on the contemporary roll call of mass shootings at schools. The first of what would turn into an onslaught. The town that will always be 15 years ahead of Newtown in the healing process.

There had been a handful of others in the months beforehand — that February two had been killed and two wounded at Bethel Regional High School in Alaska; that October, three had been killed and seven wounded at Pearl High School

in Mississippi — but it was Paducah that raised the specter of a trend, a sign that something was new and very wrong.

“In my whole life, it had never crossed my mind” that someone would shoot up a school, Bond told the local NBC affiliate during an interview on the 20th anniversary earlier this month. “Now, there’s not a high school principal in the nation that … it doesn’t flick in his mind sometime every day.”

So much else that happened in Paducah would eventually become familiar pieces in the response to shootings. There were lawsuits. The parents of the victims sued the parents of the shooter, eventually settling for $42 million — money that, practically, they will never receive. Lawsuits against the manufacturers of violent and pornographic video games, movies and websites were less successful, and were eventually dismissed.

There were broken families. After 15-year-old Kayce Steger died, her parents dealt with their grief in different ways, leading them to divorce.

There was PTSD. Kayce’s mother, a nurse, could not walk into the ER of the hospital in which she works. And eventually there was the rift between those in the community who felt it was time to move on and those who felt they were being told to forget. Former students became outraged recently when they realized the memorial to their murdered classmates had been locked behind a gate rather than in a place any student could visit and reflect. Access has been restored.

There were some who forgave — most notably Missy Jenkins, who was paralyzed from the waist down that day, and who got married, had two children and is now a day treatment counselor at a nearby school. She visited her assailant in prison (he was sentenced to 25 years to life) and, she said, “I did not forgive him to make him feel better. I forgave him to make me feel better, to help me move on.”

There are others who can’t quite forgive themselves. Bond still wonders which lives he might have saved “if it had only taken eight” rather than “12 seconds” for him “to get that gun.” He stayed at Heath until the last of the survivors graduated, then crafted a career as a consultant on middle school safety. He just retired from that role, and says his last interview on the subject was the one he gave to the local news on the 20th anniversary.

He has visited 15 schools in the immediate aftermath of a shooting incident, he said, jumping on a plane sometimes within hours of the news because “I needed to go help those people. I know how bad I needed help and there wasn’t anybody who had been through it. There wasn’t anybody coming.”

_____

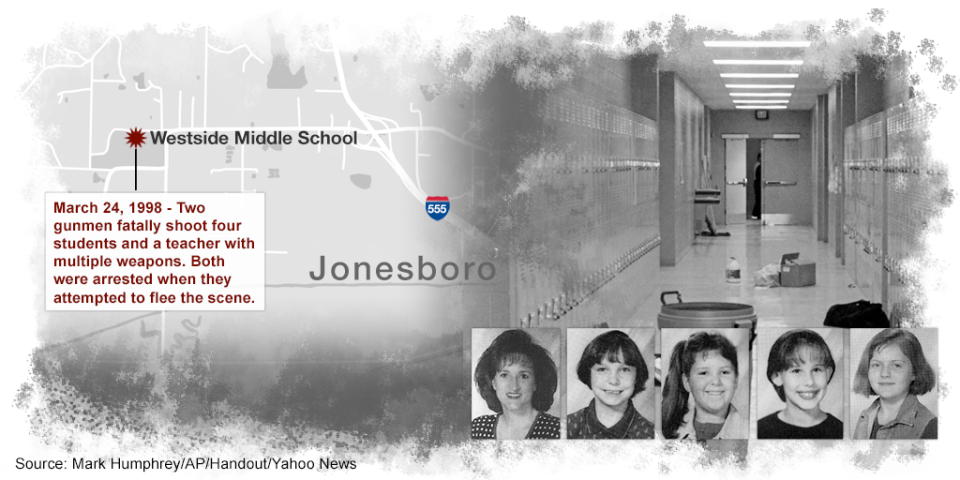

The chain of grief that originated in Paducah next appeared less than 200 miles away in Jonesboro, Ark. Karen Curtner, the 35-year-old founding principal of the two-year-old Westside Middle School, knew about the shootings the year before, but still, she first thought that the wailing alarm she was responding to on the morning of March 24, 1998, was either a malfunction or a prank.

Some of her teachers already suspected it wasn’t actually a fire; someone had seen a sixth grader, Andrew Golden, pull that alarm and dash outside. But “when the fire alarm goes off, you know what the rule is,” she recalled recently in an interview with Yahoo News. “Everybody leaves.”

Everybody did. Students and teachers were gathering on the lawn when Curtner stepped out of the building and heard the next sound. “My parents, everybody I’ve ever been around, have always been hunters,” she says. “So I knew what it was.”

What she means is that she knew it was the sound of rifle fire. What she didn’t yet realize, because it was so unthinkable, was that 11-year-old Golden had pulled the alarm in order to lure the entire school outside and that he and his 13-year-old schoolmate Mitchell Johnson were now standing in the woods and shooting guns they’d stolen from Golden’s grandfather.

Four students and a teacher were killed that day, and 10 others were wounded, many severely. While there was press coverage of Paducah, it was nothing like what happened in Jonesboro — the first time the satellite trucks descended in such numbers that there appeared to be more journalists than residents. At least one who said he was a journalist turned out to be a stalker — police found piles of newspapers in his car with Curtner’s photo circled in most of them.

With the press came national attention, some of it welcome (victims of the Oklahoma City bombing sent piles of teddy bears to comfort the students), much of it not. (There were threats against both staff and teachers from many, including one letter purportedly from the Unabomber, praising the shooters.) There were almost too many letters to read, but when the one from the mother of one of the girls killed in Paducah made its way to Thetford, “I remember just holding onto it and crying,” she says. Hearing “from someone that I felt actually understood what we were going through meant more than words could ever say.”

Garth Brooks contacted Curtner about performing a benefit concert, and Tiger Woods wanted to hold a golf tournament to raise money for the victims. Curtner said no to both because her focus was on getting her school “back to normal.” Like Paducah, “normal” for this community would prove to be a hazy and moving target. Marriages ended. Families moved. Lawsuits were filed.

Depression and survivors’ guilt settled like a fog. Brandi Varner later told a reporter that she’d spent much of her little sister’s funeral wishing she’d tried harder to get Britthney to skip school the day of the shooting, since they’d both stayed up so late watching the Oscars on TV the night before. Thetford, a social studies teacher nearly killed by a bullet to her abdomen, spent much of her time thinking about her friend Shannon Wright, the one teacher who was killed. Wright was younger than Thetford; her child was younger than Thetford’s. Why did Wright die but Thetford live? Then one day Thetford found herself saying to her mother, “I don’t understand why Shannon got to die and I had to stay here.” That’s when she sought counseling.

Life changes were made. Some of those were a response to triggers — Thetford, for one, found herself crying while searching for a video to accompany a lesson on trench warfare during WW I. She decided in that moment that she had to stop teaching social studies, because so much of the curriculum was about violence.

Some were a response to grief — Britthney’s mother and stepfather divorced, because, her mother would say later, she withdrew her love from her husband for fear of ever losing someone she loved again. Older sister Brandi, in turn, went “buck-ass crazy,” as she described it to reporter David Peisner 15 years after the shooting, by which she meant she started drinking, smoking pot and having sex. She was expelled from high school, but turned into a “super-protective” parent of her two children. When her youngest child, a daughter who looked a lot like Britthney, started school, Brandi insisted she attend the smallest possible magnet school to make it easier for her to keep track of how all the other parents stored their guns.

And some of the changes were a response to fear. Like Paducah, Jonesboro is unusual in that the shooters lived. Unlike Paducah, or any other place where there was a school shooting, these shooters were released on their 21st birthdays — Johnson in 2005, Golden in 2007. Johnson was soon re-imprisoned for carrying an unregistered gun, but has since been released and is living in Texas; Golden now lives in Missouri and has been married at least once. He changed his name to Drew Grant, and used that name to apply for a permit to carry a concealed weapon; he was denied after a standard fingerprint search.

This leaves many in Jonesboro afraid one or both will come back to finish the job. One teacher told BuzzFeed News that she’d gone so far as to move to a new house with a different phone number and change her appearance, including losing 100 pounds, so that she would be unrecognizable to her former student.

With so many feeling this much, it was almost inevitable that they would collide over time with those who felt it was time to move on. Thetford, for instance, gave interviews after many other victims had stopped, because, she said, she wanted to share the renewed faith in God that she had found in her near-death experience. Then one day she opened a letter accusing her of grandstanding and “enjoying the notoriety.” It warned her to “SHUT UP.”

_____

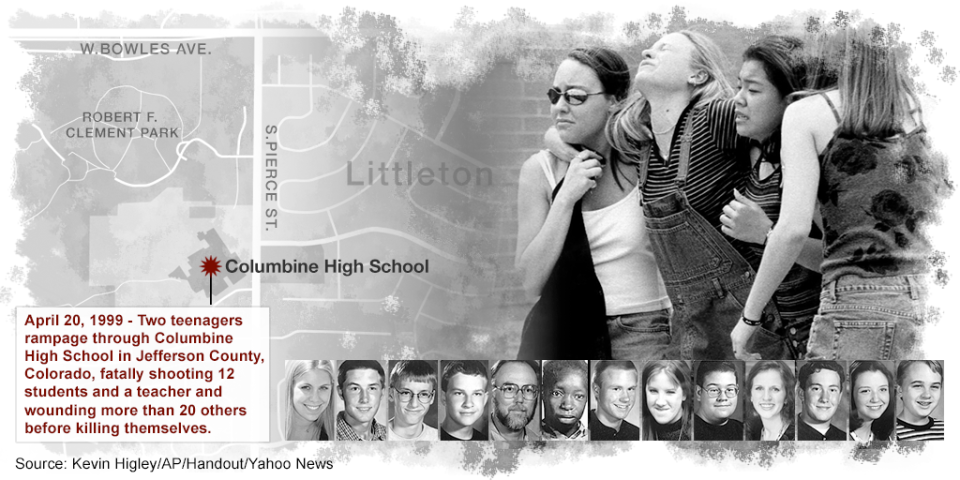

Karen Curtner first heard when a reporter called, asking for comment. “Oh, God, not again,” she said, turning on the television in her Westside Middle School office on April 20, 1999, to watch what was unfolding at Columbine High School, three states and 1,000 miles away.

Lynette Thetford, in turn, who had not yet stopped teaching social studies, was in her classroom that day, with its view of the playground where she’d been shot just over a year earlier. As other teachers came to warn her, they formed a circle, held hands, and began to pray.

There had been seven school shootings and 15 fatalities since the one in Jonesboro. Now this one, in Littleton, Colo., was being carried live on national TV. Two students went on a rampage through the building, killing 12 classmates, one teacher and then themselves.

The aftermath — the lawsuits, the failed marriages, the fights over donated money, the desire by some to just get over it already — was familiar. But Columbine caught hold of the nation’s attention like none that had come before, both because of the number of victims (at the time it was the largest school shooting in the United States) and the new 24/7 news cycle. (The Columbine graduation a month later was also carried live, by CNN.) Columbine was also the tipping point. Following Paducah, Jonesboro and others, the idea of a teenager shooting his classmates looked like a grim trend, an evil infecting America’s children. “The Monsters Next Door” read the cover of Time magazine. Newsweek asked, “Why Did They Do It?”

Gradually the spotlight dimmed, leaving the community to piece itself back together in the new shadow. Much of that fell to Frank DeAngelis, the principal of Columbine, who was still suffering the personal aftershocks of facing down the student killers. As he walked out of his office moments after the shooting began, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold were marching toward him, long guns blazing. One bullet hit a glass wall directly behind DeAngelis’s head, he said in an interview with Yahoo News. Seeing the girls’ volleyball team heading up the hallway toward the shooters, DeAngelis diverted them into a nearby closet, probably saving their lives.

The lives he didn’t save haunted him, however, and through the summer, while planning for the reopening of the school (students finished the academic year in space shared with another district high school), he was also trying not to fall apart. He kept seeing the shooters coming toward him, the killers they were juxtaposed with the boys he thought he knew — middle schoolers in their soccer uniforms, missing teeth; seemingly happy seniors, high-fiving him at the prom two weeks earlier.

He spent nights alone in his basement “with a stiff drink and my golden retriever,” unable to unsee the school’s library, where most of the victims died, with FBI markers and blood still on the floor. When he managed to sleep, it was fitful, and he often woke by 3 a.m. and went to sit in the local church until dawn.

Thrice-weekly counseling and a feeling of responsibility got him through that summer. “There wasn’t a template for rebuilding a school and holding a community together,” Bond said. “Frank built that template.”

Bond called DeAngelis to offer his support. Thetford went to Littleton during Jonesboro’s summer break to tell residents, “It won’t ever be OK, but it will get better.”

Frank Ochberg made regular visits too. A clinical professor of psychiatry at Michigan State University and a member of the team that first formulated the PTSD diagnosis, Ochberg was developing a sad subspecialty in healing after mass shootings. The students would likely do better than the adults, he counseled, because more resources and care would inevitably be focused on them and because they are more resilient.

With advice from all corners, Columbine High School reopened in August 1999. A phalanx of parents formed a line by the entrance, welcoming the students back with a show of emotional support, and physically shielding them from the press. The library was closed, though not yet torn down and rebuilt. The walls were repainted in shades that psychologists had advised were soothing. A new aquarium was there for the same reason.

Copious attention had been paid to the fire alarms. Those alarms had wailed for the entire five hours it took police officers to rescue students from their hiding places in April, and one thing learned in Jonesboro was that the sound of any alarm, but particularly that same alarm, would trigger emotional tsunamis in those who had been there that day.

DeAngelis had spent hours in meetings with alarm companies “coming up with sounds that were different to what we had used prior.” All around the country, schools had started responding to the wave of shootings by initiating lockdown drills, but those were a fraught subject at Columbine.

“We couldn’t just say we don’t have to do drills,” DeAngelis recalled. “So we did them in baby steps.” First there was a version where teachers quietly told students to stand where they would if they were evacuating for a fire. The next step was to add the sound of the alarm only after everyone had taken their places outside the building. Eventually DeAngelis would give advance warning that there would be a fire drill the next day — some parents chose to keep their children home — and would count down on the PA system to the moment the alarm went off so it wouldn’t take anyone by surprise.

For months, then years, DeAngelis found himself trying to balance the needs of those who wanted to move on with those who could not.

“There were those who felt the sooner I stop talking about it, the sooner they could heal,” he said. “A lot of people felt that if we could just get back to doing what we were doing we will be OK. I respectfully disagreed. To think you are going to forget about what happened that day just because you go back to resuming your daily activities? It’s not going to happen.”

He pledged to stay in the job until 2002, when the last class who’d been present that day had graduated. (Eventually he expanded that pledge to any student who had been in a preschool feeder school, and didn’t retire until 2014.) As happened at Paducah, Jonesboro and others, though, his staff began to leave.

“Bill Bonds warned me early on that ‘within four years 75 percent of your staff members will be gone,’” he recalled. “I said, ‘Bill, that’s not going to happen.’ What I didn’t anticipate is the impact of walking into the building each day. People who during summer break seemed to be doing well … walked back in and their blood pressure went up.” Attrition increased dramatically, and by the time DeAngelis retired, only 10 percent of the original staff was left.

Also as predicted, he said, the students did prove to be resilient. The Columbine classes of 1999 through 2002 — the students who were in the building on the day of the shooting — are still unusually close-knit, several members say.

“We get together for barbeques, we play fantasy football, most of us have kids,” Patrick Ireland, who still carries shrapnel in his brain and who had to relearn how to do practically everything, told Yahoo News. The owner of a wealth management business near Denver, his children are now 7 and 3, and “things are great,” he said. He still gets a flood of supportive texts and phone calls every April 20, “saying, ‘I’m thinking of you,’” he said. But during most ordinary days, he believes “this was one event, this was something that happened — something that we want to acknowledge and understand, but it’s not going to be the thing that defines me as a person.”

DeAngelis says the class he still worries about most is the Columbine Class of 1999 — students who graduated on May 22, a month and two days after the shooting, then dispersed to college and work. “There wasn’t support for them,” he said. “The kids and staff who returned, it was tough, but we had each other. The ones who left, they would be sitting in class and the fire alarm went off and they found themselves having a meltdown and they weren’t sure why. Or they’d be doing well and five years down the line they would lose it and the help is not there.”

In the same way, he said, he worries about mass attack victims who do not have a community — those who randomly happened to be watching “Batman” in Aurora, or a concert in Las Vegas, or even working in various offices in the World Trade Center.

Visiting Virginia Tech for the first anniversary of the shooting there, he told faculty and students, “The difference for you compared with Columbine or Paducah or Jonesboro is you had kids coming from everywhere — different states, different countries — then going back there. For Columbine, the people lived in our community; we had a sense of community. At first that creates a bigger wound, but I also think it helps with the healing.”

Watching the students heal helped DeAngelis too. Over time, he said, “I got to the point where when I was coming out of my office, I wasn’t seeing the gunmen coming. Instead I saw Lauren Townsend playing volleyball, I saw Isaiah Shoals high-fiving me, I saw Rachel Scott on the stage performing, I envisioned Danny Mauser and Kelly Fleming down at church. I saw these kids not dying in our school, but living in our school.”

As he started to heal, he also started making phone calls. “You’re not going to remember anything we talk about today,” he would say when he got a shaken community leader on the line, “but please take down my number and call me if you ever need anything.”

_____

As news poured forth from Newtown, Conn., on Dec. 14, 2012 — 151 shots fired in five minutes; 26 dead, including 20 first graders and six of their teachers at the Sandy Hook Elementary School — Coni Sanders received a call from her mother, Linda.

William “Dave” Sanders, who was Coni’s father and Linda’s husband, was the one teacher killed at Columbine, and in the 13 years since, Linda had not moved past her grief. Still living in the home near the high school, keeping the house “like a shrine” to the day her husband left it for the last time, Linda was now sobbing and shrieking in pain.

“’It’s Christmas, it’s Christmas,’” Coni, who became a forensic psychologist working with violent offenders, remembers her mother saying. “’Those babies, those babies, those babies.’”

Said Coni: “I seriously thought I was going to lose my mom.”

A few blocks away, hours to days later, Frank DeAngelis was also “having a meltdown” during a phone call. He’d been offering a shoulder to someone in Newtown when he began shaking and sweating. He grasped the medals he’s worn around his neck since 1999 — a crucifix, the Blessed Virgin — and rubbed them rhythmically to calm down. Then he continued pacing, stroking, talking.

There had been 92 school shootings between Columbine and Newtown, and with each, particularly the larger and more publicized ones, those who came before watched as those who came after became part of the “club that no one wants to join,” as DeAngelis calls it.

Jonesboro sent teddy bears to the children of Newtown — more than 6,000 of them filling two 18-wheelers — just as Oklahoma City victims had done for Westside students, some of whom still had theirs 13 years later.

A three-car caravan of former students drove to Connecticut from Red Lake, Minn., because when a 16-year-old student killed 10 and injured seven at Red Lake High School in 2005, several Columbine survivors had driven out to see them.

Those with personal experiences of school violence joined with those who had not, and soon the entire country seemed to be sending stuff to Newtown. Eventually the town assessor would recruit 580 volunteers over the months to work in a donated warehouse sorting and cataloging it all: a total of 63,780 teddy bears, 636 boxes of toys, more than 2,200 boxes of school supplies and a stunning number of boxes of tissues.

President Barack Obama came, later calling Newtown the toughest day of his presidency, and telling a packed and tearful interfaith vigil, “I am very mindful that mere words cannot match the depths of your sorrow, nor can they heal your wounded hearts.”

Vice President Joe Biden came after that, meeting privately with grieving parents, recalling the loss of his own wife and young daughter in a car crash decades earlier. Nicole Hockley, whose son Dylan was among those killed, remembers Biden’s advice to keep a daily journal, ranking each day from one to 10, “where one is the worst and a 10 is the best.”

His message, Hockley said, was “You may never have a 10 again, but over time you’re going to see that you’re getting into the fives and the sixes and sevens, and then you’re going to go backwards again and be at the low numbers, and then you’re going to move forward again. And then that’s something useful to look back over time to say, ‘I made it through.’ ”

To the earlier waves of survivors watching from afar, everything about Newtown was familiar, but also bigger. Where Paducah turned away celebrities’ offers to help, Newtown was flooded with them: Giants receiver Victor Cruz visited the family of one little boy who had been buried in the player’s jersey; Harry Connick Jr. visited the family of another victim, whose father had played in Connick’s band. James Taylor gave a concert for family members of the dead at the local church and sang “Sweet Baby James” — to a family whose son had carried that name.

Where a few parents of earlier shootings had become crusaders — Suzann Wilson lobbied for the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence after Britthney died in Jonesboro, and Tom Mauser, literally wearing the shoes of his murdered son Daniel, lobbied for local and national gun control after Columbine — Newtown raised the participation and the stakes. Obama sent Air Force One to bring families to Washington, where they walked the halls of Congress with photographs of their dead 6- and 7-year olds, lobbying for expanded background checks on firearms.

And when the measure failed, disillusionment came with a new forcefulness too. “Why wasn’t Sandy Hook the mass shooting that changed everything?” Vice News asked in a headline. Then reporter Matt Taylor answered that question: “Mass shootings are increasingly accepted — by about three quarters of us — as an essential part of American life, like fourth of July barbecues and binging on Netflix. We simply don’t see a way out, and don’t have much or any confidence that our leaders will craft one.”

The frustration, layered as it was upon recent grief, turned things ugly for a while in Newtown — another way that the community followed the same path as other places, but more so. Feelings, so close to the surface, were easily shattered. As New York magazine writer Lisa Miller wrote on the first anniversary: “There were 4,000 free tickets to a July Yankees game, an amazing boon, but 4,000 is less than a fifth of the town. NASCAR memorialized the Sandy Hook victims with a special car at the Daytona 500, and the fire chief who had stayed outside Sandy Hook Elementary that morning had the honor of unveiling it, not the police chief, who had entered the school.”

Just as stuff was becoming a surrogate for sympathy, so was money. More than $20 million was sent to Newtown from around the country, divided among 70 charities, the largest of which was the $11 million collected by the United Way. There were months of arguments between the families of those killed, the families of children who had witnessed horror and escaped, and the administrators of the United Way over whether the donations had been sent to help the victims directly or to help heal the town in general.

The fighting, in turn, spurred a backlash from those who felt the families should grieve more quietly, or more tastefully, or just move on already.

“With every shooting we’ve taken this process and we’ve fast-forwarded it,” Coni Sanders said. “We do it very quickly. Columbine stayed closed for months. The bodies weren’t removed for days. In Las Vegas it was business as usual the next night.

“I think a lot of that is by design,” she continued, speaking as a psychologist as well as a victim. “People not directly affected are overwhelmed by the number of tragedies, the number of deaths. I sometimes feel guilty because when Columbine happened there was such an outpouring. They canceled sporting events — well, except for the gun show, that went on. But stores closed. There was a special post office for all the mail we were getting. There was recognition that this wasn’t just an event, it was a change in how we existed.”

Now communities are left relatively unmoored to navigate the aftermath on their own. Those who have been there warn that at only five years in, Newtown still has a long way to go. Dave Cullen, whose seminal book, “Columbine,” came out 10 years after that shooting, and who still keeps in close contact with many survivors, noted that “those who were going to be OK were OK by 8 years or so. But lots are still not OK.”

Anniversaries, they warn, will continue to be hard. “That first year was just a constant trying to make it through, wondering how much more could you take,” Curtner said. The second year brought the realization that time did not heal quickly, and by now, with the 20th anniversary looming in March, she said, “it’s not so much today like it was the first five years or so,” but “it never goes away. It gets better, but it never goes away.

Memories, they say, will continue to be triggered by all the senses. For Thetford it’s unseasonable warmth, because the weather that day in March when she was shot felt like May. This past February the thermometer reached 70, and she left the school where she now works and drove over to Westside, just to be there.

For Coni Sanders it’s springtime noise. “One night I said to my husband ‘Oh, my God, what’s with those helicopters? Why are there so many around?’ And he said, ‘They’re always there; you just notice them in April.’”

The parents of Newtown say they are coming to understand all this — that five years is not long enough, that grieving is not binary or linear.

“There’s not going to be a point where we can put an ‘ed’ on the word ‘recover,’” said Michele Gay, mother of Josephine, who, with Alissa Parker, mother of Emilie, formed Safe and Sound Schools to promote safety in schools. “It’s always going to be an ‘ing,’” she said in an interview with Yahoo News. “We’re always going to be in process with this.”

Some of the most jarring reminders have been removed. The building where the shooting happened was completely torn down — after construction crews signed nondisclosure agreements that no photos of the interior or bits and pieces of the school ever be made public or sold. The $50 million, fresh-start of a structure that replaced it was opened to students in August of last year, filled with the latest in whimsy (indoor treehouses) and security features (bulletproof windows, doors that automatically lock from inside when closed).

But when you’ve lost a child, the parents have learned, everything becomes a reminder.

One night earlier this month, Mark Barden, whose son Daniel died at Newtown, was driving his daughter Natalie to her piano lesson when the Christmas lights along the route made him remember another ride to Natalie’s piano lesson, this one with Daniel along for the ride.

“We played Christmas music in the car with Natalie and Daniel, and I noticed Daniel was crying as we listened to one of the songs because it touched him so deeply,” Mark said. With a jolt he realized that what he was remembered had happened five years ago to the day, on Dec. 6, 2012, a week before Daniel would die.

Some families have moved away, but most have stayed. Daniel’s parents considered leaving. “Jackie was ready to be away from everything and anything that reminded her of the tragedy,” Barden said – but then they asked their surviving preteens, James and Natalie, if they wanted to move. “They were both like, ‘Why would we want to go anywhere else?’ Everything we know and love is here.’”

Dylan Hockley’s parents discussed leaving town too, but chose to stay, in part, to be near others who shared their grief. “I don’t think you can run away from your problems,” Nicole Hockley says. “There’s always going to be Christmas lights, there’s always going to be 12/14, and I think here, there is a fantastic network of support and a community that has felt the varying degrees of tragedy, and there’s an understanding here that can’t be found elsewhere. This is where we choose to live.”

Many also choose to do as others did for them, to pay it forward as others join their tearful club.

After 26 were killed during a Sunday church service in Sutherland Springs, Texas, Hockley tweeted a note of condolence to the families of the victims on behalf of Sandy Hook Promise. “Twenty-six might seem like an arbitrary number, until it’s your community,” she wrote. “When your son is one of the 26, the number will take on new meaning. When your wife is one of the 26, the number will take on new meaning. These aren’t just numbers — they are people.”

And after two students were shot by an intruder posing as a student in Aztec, N.M., last week, Sandy Hook Promise reached out to those parents as well.

Near the end of that day, while police were still inside Aztec High School, Mayor Sally Burbridge released a statement: “There will be a Prayer and Candlelight Vigil this evening … in Minium Park. Please join us in beginning the healing process for our community.”