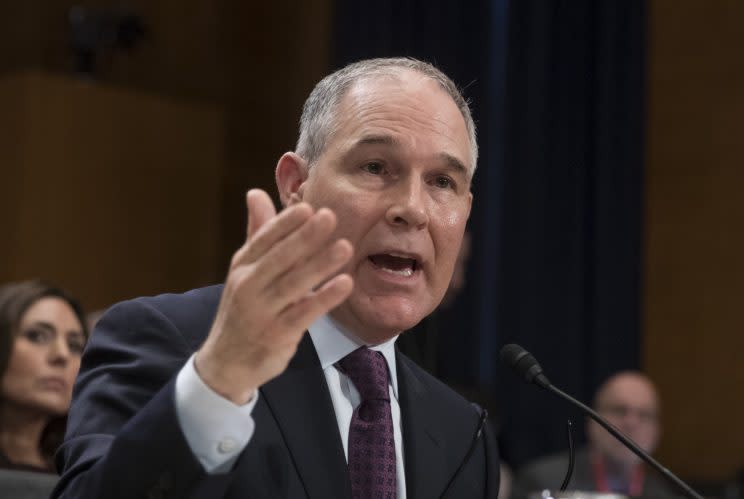

Scott Pruitt on climate change: ‘My personal opinion is immaterial’

Pressed by Democratic senators for his views on the causes of climate change, the Trump administration’s choice to run the Environmental Protection Agency insisted at his confirmation hearing Wednesday morning that his “personal opinion” was “immaterial” to how he would do his job.

Democrats on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee questioned Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt closely on his history of suing the agency he has been nominated to lead, his statements questioning mainstream climate science and his close ties to the oil and gas industries. Republicans were much friendlier, mostly lamenting the impact of regulations on fossil-fuel industry jobs, something Pruitt promised to take into account.

Coincidentally, the hearing came as two leading scientific agencies — NASA and NOAA, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration — announced that 2016 was the hottest year in history, the third consecutive year that global temperatures set a new record. Stretches of the Arctic Ocean, they said, were an astonishing 20 to 30 degrees Fahrenheit above normal.

Pruitt is part of a group of state attorney generals that is suing the EPA over the Clean Power Plan, which was first proposed in June 2014. It aims to fight anthropogenic climate change by limiting greenhouse gas emissions related to electricity generation from power plants. He has been involved in more than a dozen other lawsuits against the EPA.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., had a particularly heated exchange with Pruitt over the overwhelming scientific consensus that carbon emissions from human activities are the primary cause of the climate change that’s already had destructive consequences around the world.

“As I indicated in my opening statement, the climate is changing and human activity contributes to that in some manner,” Pruitt said.

“In some manner?” Sanders said. “97 percent of the scientists who wrote articles in peer-reviewed journals believe that human activity is the fundamental reason that we are seeing climate change. You disagree with that?”

In defiance of mainstream climate science, Pruitt insisted, “There should be more debate” over whether human activities are actually contributing to climate change. Sanders pushed back and asked Pruitt to provide an explanation as to why the climate has been changing.

“Well, senator, the job of the administrator is to carry out the statutes as passed by this body,” Pruitt said.

“Why is the climate changing?” Sanders asked again.

“Senator, in response to the CO2 issue, the administrator is constrained by statutes…” he said.

“I’m asking your personal opinion,” Sanders insisted.

“My personal opinion is immaterial,” he responded.

In disbelief, Sanders said, “Really? You are going to be the head of the agency to protect the environment, and your personal opinions about whether climate change is caused by human activity and carbon emissions is immaterial?”

“Senator, I’ve acknowledged to you that the human activity impacts,” Pruitt said.

Sanders shot back: “Impacts? The scientific community doesn’t tell us it impacts. They say, ‘It is the cause of climate change. We have to transform our energy system.’”

When asked if he believes the U.S. must change its energy system, Pruitt repeatedly dodged the question and answered along these lines: “I believe the administrator has a very important role in regulating CO2.”

In response to questions from Delaware Sen. Tom Carper, Pruitt did distance himself from President-elect Donald Trump’s pledge, as a candidate, to “get rid of EPA in almost every form.”

Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., hammered Pruitt for sending a letter principally drafted by Devon Energy in October 2011 to the EPA disputing findings that methane is about 30 times more potent as a heat-trapping gas (volume for volume) than carbon dioxide. The energy company, which had a vested interest in downplaying the devastating effect of methane, directly contributed 979 out of the letter’s 1,016 words — roughly 97 percent.

Merkley accused Pruitt of using his office as a direct extension of an oil company rather than for the health and interests of the people of Oklahoma.

Democratic senators questioned Pruitt closely on his philosophy of regulation, which the nominee described as “cooperative federalism.” For Democrats, especially those from Eastern Seaboard states downwind from the industries and utilities of the Midwest, letting states regulate their own emissions amounts to a prescription for doing nothing. Air and water pollution does not stop at state lines.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., asked Pruitt to address 14 lawsuits in which Pruitt specifically fought the EPA’s attempts to reduce air pollution. Among other issues, Pruitt challenged mercury and air toxics standards, national ambient air quality standards, carbon dioxide emissions standards from new power plants and the Clean Power Plan.

Booker, a former mayor of Newark, N.J., was particularly concerned with Pruitt’s unsuccessful lawsuit against the EPA challenging the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR). Scientists estimate that every year in the U.S. the CSAPR saves up to 34,000 lives and prevents 400,000 asthma attacks.

“The fact pattern on representing polluters is clear. You’ve worked very hard on behalf of these industries that have their profits externalized; negative externalities are their pollution,” Booker said.

Pruitt dismissed the notion that he’s a tool of the fossil-fuel industry. He said he was representing the interests of his state. But Booker accused Pruitt of standing up for polluters at the expense of Oklahomans’ health.

According to data published by the nonpartisan American Lung Association, more than 111,000 children in Oklahoma (more than 10 percent) suffer from asthma. That’s one of the highest asthma rates in the United States.

“You’ve been writing letters on behalf of polluting industries. I want to ask you, how many letters did you write to the EPA about this health crisis? If this is representative government, did you represent those children?” Booker said.

Pruitt said the state of Oklahoma would need to “have an interest” before it could bring cases on issues like cross-state pollution: “You can’t just bring a lawsuit if you don’t have standing, if there’s not some injury to the state of Oklahoma.”

Booker interjected, “Injury? Clearly, asthma is triggered and caused by air pollutants. Clearly, there is an air pollution problem. And the fact that you have not brought suits [at any level against] the industries that are causing the pollution is really problematic.”

Pruitt was introduced at the hearing by Sen. James M. Inhofe, R-Okla., who has a wide reputation as a friend of the fossil-fuel industry and a denier of climate science. He described the nominee as a “good friend” who has built a reputation for keeping the federal government in check by fighting overreach.

“Pruitt will ensure that the agency fulfills the role delegated to it by Congress — nothing more and nothing less,” Inhofe said. “Oklahoma is an energy and agriculture state, but it’s also a state that knows what it means to protect the environment while balancing competing interests.”

Inhofe made much of Pruitt’s role in helping to resolve a long-standing dispute over water rights involving Oklahoma City and two Indian tribes, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. Other Republicans also gave considerable weight to EPA’s relatively popular role in enforcing the Clean Water Act — and to jobs.

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., sided with Pruitt in his battles against the EPA. She accused the EPA of failing to take into account the devastating impact its policies would have on coal-mining jobs in her region.

“For the past eight years, the EPA has given no indication that it cares about the economic impact of its policies,” she said.

Similarly, Sen. Deb Fischer, R-Neb., said her state’s public power utilities are “grappling with how they could ever comply” with the EPA’s restrictions on carbon emissions. Nebraska farmers, she said, are waiting for new technology that’s stuck in a “broken regulatory process,” and biofuel investors face uncertainty under the Renewable Fuel Standard program, which aims to replace petroleum-based fuel with clean energy.

“As a result of the activist role the EPA played for the past eight years, families are concerned about the future of their livelihoods,” she said.

Read more from Yahoo News: