'The screams were blood-curdling': Before Cameron Williams died at Waupun, prisoners say he begged staff for help

For two months, Cameron Williams lived in solitary confinement in a tiny cell at Waupun Correctional Institution.

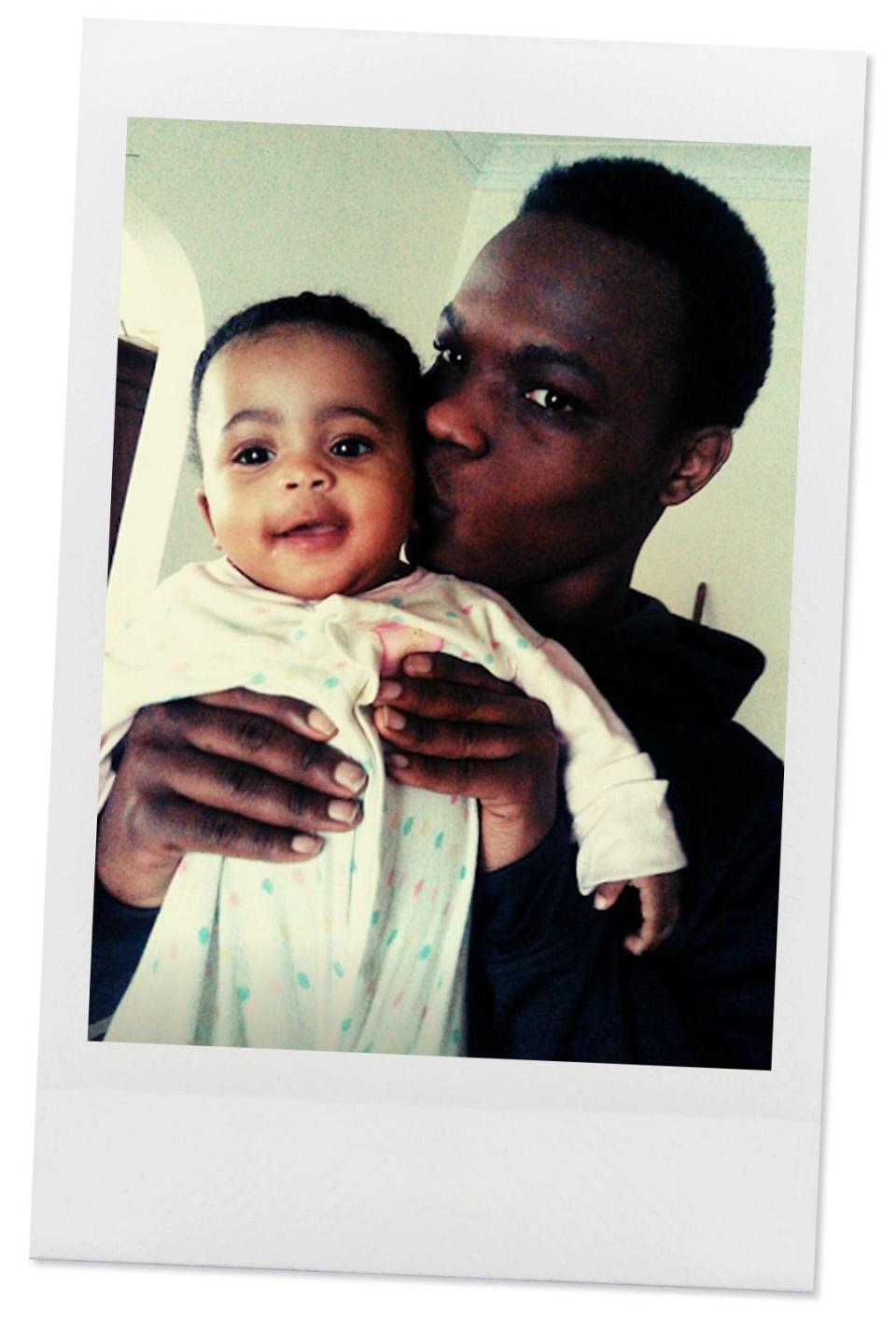

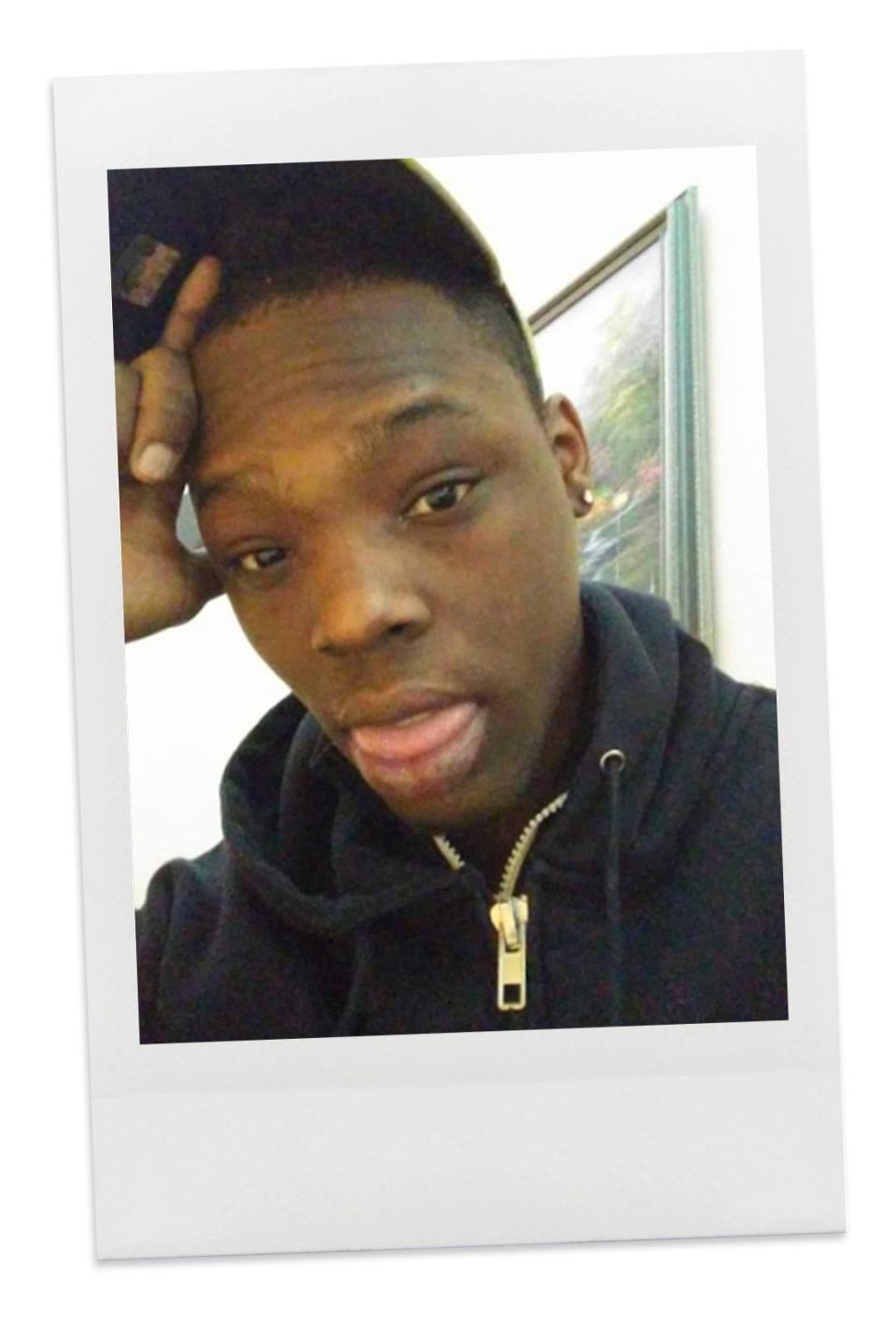

There, others incarcerated in the same housing unit said the 24-year-old often entertained them by talking and singing all day.

But last October, Williams began crying and begging to go to the emergency room, they said.

“The screams were blood-curdling,” Robert Ward later wrote in a letter to the Journal Sentinel. “No one came to help him.”

That evening, after many hours of screaming, Williams fell silent. For the next 36 hours, prisoners said, no one saw or heard from Williams, even at mealtimes, as they pleaded with correctional officers to check on him.

On the morning of Oct. 30, 2023, staff found Williams dead in his cell.

Williams is the third of four prisoners to die at the maximum-security facility in the past eight months. At the time, he was serving a three-year sentence for burglary — he'd pushed a woman to take her purse — and was potentially facing several more years on charges of assaulting prison staff.

Williams’ death comes at a time when the treatment of people in Wisconsin’s prisons is under close scrutiny. After the Wisconsin Department of Corrections put multiple prisons on lockdown last year, including Waupun, incarcerated people reported spending virtually 24 hours a day in tiny cells with little to no access to visitors, outdoor recreation or medical care.

Although the restrictions are gradually being lifted, incarcerated people and their advocates say the Department of Corrections has long been ill-equipped to handle the mental and physical health needs of the people in their care.

In March, more than four months after his death, the Dodge County Medical Examiner ruled Williams' death a stroke caused by "multifocal cerebral venous thrombosis," or multiple blood clots in the brain.

Dr. Diane Book, an associate professor of neurology and stroke specialist at Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, said the warning signs of this type of stroke can vary, but the most common symptom is a progressive headache over the course of many days.

“In most cases (of strokes), the symptoms are sudden and one-sided,” Book said. Williams’ "is unfortunately an unusual case,” she said. The type of stroke he died from is rare and hard to identify, Book said, but treatable if caught in time.

"Each death in our institutions is a tragedy, just as it is in the community," the Department of Corrections said in a statement, adding that the department "takes its obligation seriously to investigate and improve processes to prevent future deaths."

But the department has not released details or commented on the circumstances of the four deaths, citing health privacy laws.

Instead, the Journal Sentinel pieced together Williams’ final days through months of letters, emails and phone calls with four people held in the same unit as him. The four men allege guards ignored their repeated pleas over two to three days to check on Williams.

“He was screaming for help but nobody came,” said Davonci Hennings. “It’s just not right how they do us inmates here.”

Four months after her son’s death, Raven Anderson is left with many questions: Could her son have been saved? How long was he dead before correctional officers realized? And who was responsible?

“This wasn’t a punishment,” Anderson said. “This was torture.”

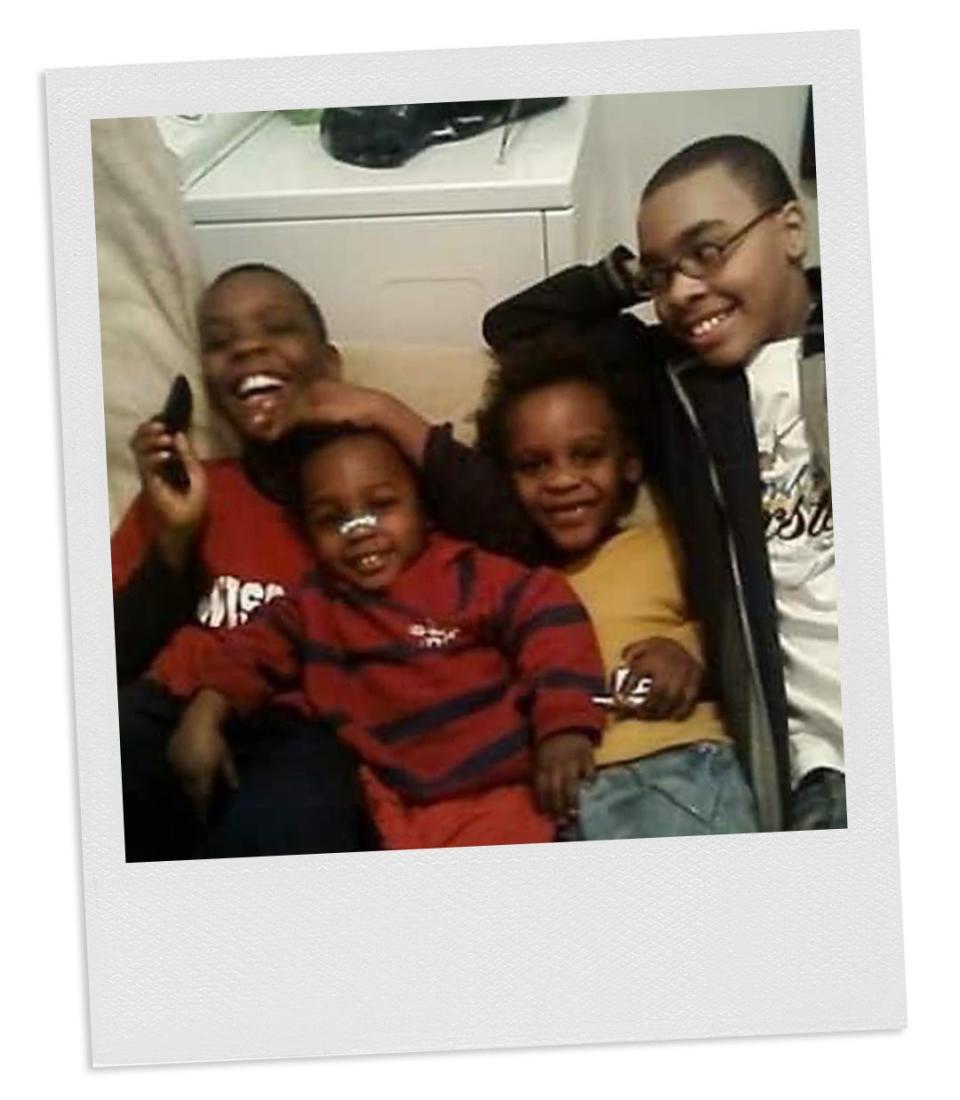

Williams’ struggle with mental health began as a young boy

Growing up in Chicago, Williams was “good in the books” but had behavioral challenges from an early age, according to family.

Medical records reviewed by the Journal Sentinel tell the story of a “very bright” boy who loved music and dreamed of going to college to become an artist. But they also describe a troubled childhood marked by domestic violence, substance abuse, stints in juvenile detention, and a history of suicidal ideation starting as early as 9 years old.When Williams was a teenager, Anderson said she sent him to live with family in Green Bay in hopes of giving him a fresh start. But between 2016 and 2017, Williams was hospitalized several times for suicide attempts both in Illinois and Wisconsin, records show.

During a stay at Winnebago Mental Health Institute at age 17, Williams was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and possible schizoaffective disorder. He was prescribed several medications, records show.

Although Williams' records suggest he was improving under the care of mental health professionals there, they also describe periodic outbursts at staff and intrusive thoughts about harming himself.

During one group music session, Williams was reported as saying: “When I sit by myself, my mind is rolling and my past comes up.”

A few months into his stay, the 17-year-old told staff: “I just want to go home.”

But not long after he left the facility, Williams was in trouble again. Following several misdemeanor offenses in Brown County, Williams was sentenced to two years in prison for robbing a woman of her purse in Green Bay in 2018.

Williams, then 19, told the judge: “I’m sorry that I wasted your time. I’m sorry that I didn’t take my medications.”

Despite his troubles, those incarcerated with Williams described him as bright and energetic.

“He was very funny (and) creative,” Hennings wrote in an email. “A good drawer, song writer.”

“He was a good kid, just a lil lost,” Ward wrote in a letter. “But we all are at some point.”

Over the next four years, as Williams cycled in and out of jails, prisons, and mental health facilities, he continued to struggle with his mental health, records show.

In 2021, during a stay at a mental health treatment center for prisoners, Williams kicked and threatened to spit on staff member, and hit one in the head with a bar of soap, according to a criminal complaint. He was charged in July 2023 with three counts of battery by a prisoner, a felony, and soon transferred to Waupun Correctional Institution, then in its fifth month of lockdown.

Within two months, he was dead.

Williams’s health began to decline in late October, prisoners say

At Waupun, Williams was soon sent to the restrictive housing unit — also known as solitary confinement, segregation, or “the hole.”

Ward and Hennings, as well as prisoners Reginaldo Etienne and Julian Blackshear, all arrived in the unit around the same time as Williams, in September 2023. There, they said they communicated with each other primarily by calling out or looking through the small windows on their cell doors.

Dant’e Cottingham, a prison reform advocate with EXPO who spent three years in solitary confinement at a different Wisconsin maximum-security prison, explained that people in solitary kept tabs on each other primarily through sound.

While it was difficult to see more than three to four cells down, prisoners could hear one another clearly, according to Cottingham.

“It’s forced on you,” he said. “You can’t do anything but hear. It's so loud.”

According to Etienne, Williams started feeling unwell around Oct. 21. Etienne, who knew Williams' family outside of prison, said Williams told him he was throwing up blood, that his vision was becoming blurry and that he was losing his hearing.

By late October 2023, Williams was placed on observation, also known as suicide watch, according to Blackshear and Hennings.

But when Williams returned from suicide watch a few days later, on Oct. 27, all four men said he appeared drastically worse.

Blackshear, who said he was about eight cells away, said Williams was “discombobulated” and “slurring his words.”

Hennings, who said he lived four cells down from Williams, described his speech as “jibber jabber.”

“(We) was used to him being the center of attention, talking/singing all day ‘til (the) point we gotta tell him to be quiet,” Hennings said. “(When) he came back, he wasn’t the same Cameron.”

The men all gave their accounts of Williams' behavior to the Journal Sentinel weeks before the medical examiner's office released its finding of cerebral venous thrombosis, a rare condition.

While the most common types of strokes are caused by a blockage of an artery, a smaller percentage are caused by bleeding — and even fewer result from clots in veins. The National Institutes of Health estimates the incidence of cerebral vein thrombosis at three to four cases per million every year.

The most common causes include infection, pregnancy, certain clotting disorders and certain medications. However, the cause is not always identifiable.

“Venous thrombosis tends to behave like a chameleon. It can look like many things and many things can look like it. That's why it's a tough diagnosis,” said Book, the stroke specialist.

As with other types of strokes, symptoms can include difficulty speaking, blurred vision, confusion, decreased consciousness, seizures, nausea or vomiting, and impaired control of the body, according to Book. But the most common symptom is a progressive headache over the course of a week or longer.

"It behaves very differently than arterial stroke," Book said. "Again, it's really a different beast."

Regardless, people suffering any kind of stroke require immediate medical help, such as the use of blood thinner or a clot-busting drug, she said.

If treated properly, most people with cerebral vein thrombosis survive.

Prisoners say Williams begged for help, but 'nobody ever came'

The men said Williams spent the next day, Oct. 28, bursting into fits of crying and pleading for help.

Ward, who said he lived three cells down from Williams, recalled him screaming out of his door that he needed to go to the emergency room, that his head was in severe pain, and that he felt like he was dying.

Blackshear, who was farther down, said he could hear Williams shouting “medical emergency.” Eventually, other prisoners joined in, he said.

“Here at Waupun, the way to sound for medical emergencies is screaming out of our rooms so the guards can run,” Blackshear said. “But nobody ever came to see him.”

According to Department of Corrections policy, security staff should contact the on-call nurse any time an incarcerated person has medical concerns. If a nurse cannot be reached, a designated supervisor should be notified. And if the person is experiencing a serious or life-threatening medical condition, they can be sent to the ER without consultation with the on-call nurse.

The Department of Corrections declined to answer questions about whether staff escalated Williams' case, per department policy..

Ion Meyn, an associate professor of law at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and former supervising attorney at the Wisconsin Innocence Project, said his experience representing incarcerated people showed him that correctional staff frequently ignore written policy.

“It’s just shocking — the kind of neglect and disregard that occurs in prison on a daily basis, regardless of whatever is written,” Meyn said. “Guards don’t follow it. They don’t.”

That night, the prisoners said, Williams fell silent.

Prisoners say they did not see or hear from Williams for more than a day

From the evening of Oct. 28 to late morning on Oct. 30 — a span of roughly 36 hours — nobody saw any movement or heard any sound from Williams’ cell, according to the four men.

During that time, they said Williams stopped responding to correctional officers.

“They kept coming to his door and asked him if he wants his meds, he don’t say nothing, and they walk off,” Hennings said. “He’s not taking his food or his (medications). Don’t you think you should say something?”

In the solitary confinement unit, food is usually offered by a correctional officer several times a day through the trap in the cell door, according to current and former incarcerated people. If the person does not get up, guards take the food with them and move on.

“Every day we kept telling the guards, ‘Look, check up on him, he’s probably dying in there, man.’ And they’d basically say, ‘Don’t worry about it, he’s good,’” Etienne said.

Etienne and others acknowledge that Williams complained frequently about medical issues and was not popular with guards.

“Cameron, he's an uppity person. He always talked s--- and whatever and stuff like that," Etienne said. "So, a lot of guards didn’t really like him like that. But that doesn’t give them a reason to excuse him or ignore him or anything.”

Around 6 a.m. on Oct. 30, Hennings said a corrections officer called out to Williams and got no response.

That same officer returned an hour later to deliver breakfast, called for Williams again without a response, and left, according to Hennings.

Around 10 a.m., he said prison staff checked Williams’ cell for a third and final time.

That’s when staff pulled Williams’ body out of his cell, Hennings said.

Etienne, Ward and Hennings said Williams’ body appeared stiff and his face was ashy and puffy. Given the state of his body, the men said they question how long he was dead before he was found. Etienne believes Williams died Saturday night, more than a day before he was officially pronounced dead.

According to Etienne, Hennings and Ward, Williams’ body was then left in the hallway as prisoners were served food.

"His voice be playing in my head," said Hennings, who said the experience traumatized him. "It's just driving me crazy from seeing the body."

That day, Anderson got a call from the Dodge County Sheriff’s Office at her home in Chicago. She said after a series of questions confirming her identity, the detective told her: “Your son was found dead in his cell today.”

Anderson still remembers the detective’s matter-of-fact tone.

“You know, just like it was nothing,” she said.

Critic says lack of communication from prison is 'heartbreakingly familiar'

Nearly five months later, Anderson remains troubled by the lack of transparency surrounding her son’s death.

The Dodge County Medical Examiner's office and the Dodge County Sheriff's Office said they are still investigating precisely when Williams died and have given no estimate of when that investigation will be finished.

The Department of Corrections, which conducts its own investigations into prisoner deaths, said its inquiry is still ongoing.

The prison's death review was completed Dec. 15 and the agency's Committee on Inmate and Youth Deaths reviewed Williams' case March 14, according to DOC spokesperson Beth Hardtke. The committee's discussions take place in closed session and its findings are not posted publicly.

The multidisciplinary committee is supposed to investigate the factors leading up to the incarcerated person's death and send recommendations for policies that need to be improved to top agency officials.

Meyn, the former Wisconsin Innocence Project supervising attorney, criticized the Department of Corrections' lack of transparency and called for outside monitoring to ensure that correctional staff are complying with laws and regulations.

“These themes unfortunately resonate and have resonated for years in terms of how prisons fail to communicate,” Meyn said. “I hear these allegations and it’s heartbreaking, but it’s also heartbreakingly familiar.”

Anderson believes her son, like many other people incarcerated in Wisconsin, was neglected and misunderstood because of his mental health disorders.

“He did have a mental illness and I don’t think that they took the time to recognize that,” Anderson said. “I want people that had acknowledgement of what was going on with my son to pay for that.”

She has retained attorney Lonnie Story, who filed a class action lawsuit against the Department of Corrections last October alleging “cruel and unusual” conditions at Waupun.

Story is also representing the family of Dean Hoffmann, the first person to die during the lockdown at Waupun. The family filed a lawsuit against the department in February alleging that correctional staff failed to administer Hoffmann his psychiatric medications in the months leading up to his suicide.

Anderson still finds her son's death hard to accept.

For months, she said the Dodge County Medical Examiner’s Office told her she could not view her son’s body due to the ongoing investigation. Anderson said the office also advised her it would not be a good idea to see it, given its condition.

When the medical examiner's office released the body, Anderson couldn't afford to have it sent to Chicago.

“I wanted his body,” Anderson said. “I wanted to have a real funeral for my son.”

Instead, her son was cremated.

Seven years after telling a staff member at Winnebago, “I just want to go home,” Williams' ashes are back in Chicago with his mom.

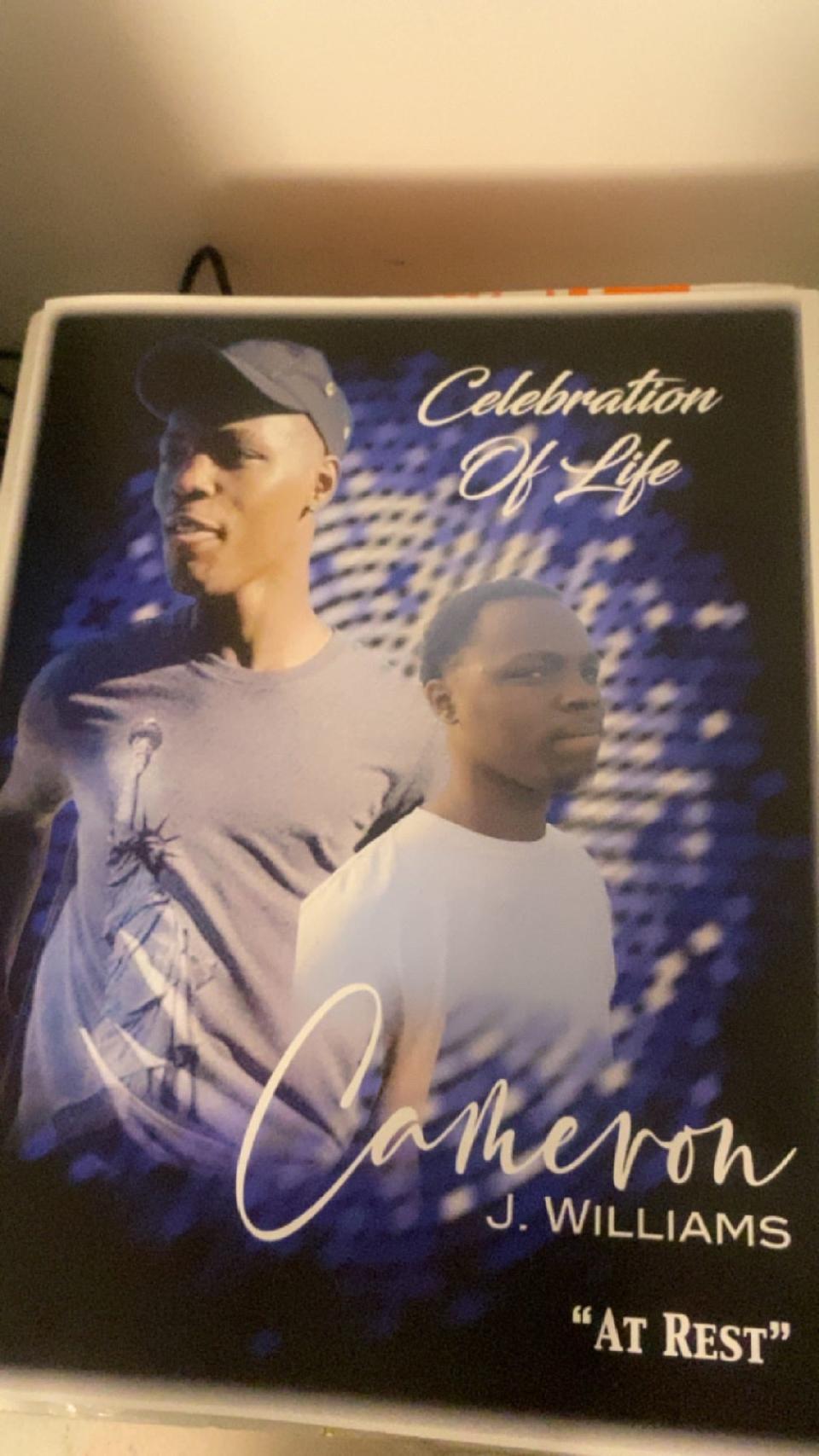

In a poster created for his celebration of life, Williams is bathed in sunlight, smiling as he looks off to his right. At the bottom, it simply reads: "At rest."

Drake Bentley can be reached at 414-391-5647 or at [email protected]. Contact Vanessa Swales at 414-308-5881 or at [email protected]. Follow her on X @Vanessa_Swales.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Before Cameron Williams died at Waupun, prisoners say he begged staff for help