Sea level rise could send U.S. 'climate migrants' fleeing to Austin, Atlanta

Sea level rise is typically thought of as a coastal problem, with cities from New York to San Francisco pondering new coastal defenses such as sea walls and sturdier buildings.

However, by making large swaths of the U.S. shoreline uninhabitable by the end of this century, sea level rise could reverberate far inland, too. In fact, every single U.S. state will be affected by climate change-induced sea level rise, a new study found.

SEE ALSO: This March was the second-warmest March in 137 years, because why stop now?

If the global average sea level rises by 1.8 meters, or nearly 6 feet, by 2100 — which is well within the mainstream projections from recent studies — 13.1 million Americans could migrate away from coastal areas during this time period, according to research published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

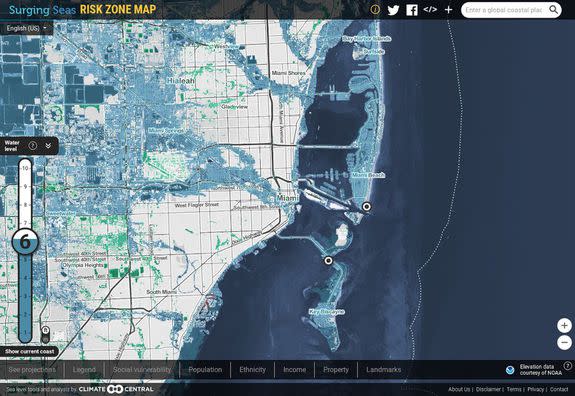

Image: climate central

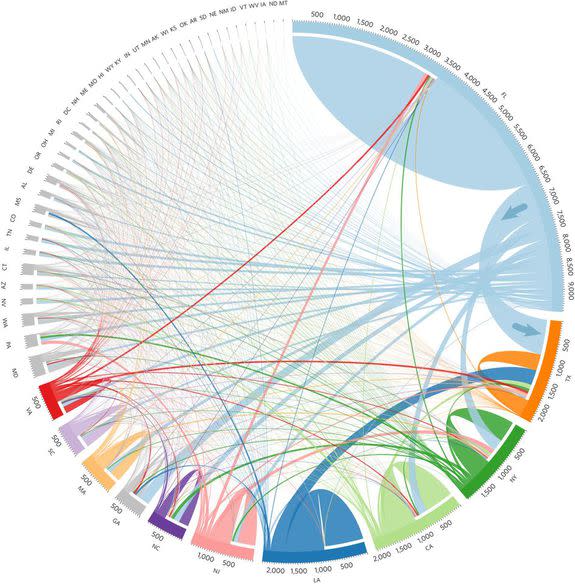

The biggest net population gain would be in Texas, which would see migrants from Louisiana, Virginia, and low-lying areas in the Lone Star State, the study found. In particular, the Austin and Round Rock area of Texas could see a net gain of as many as 820,000 people, depending how well coastal areas adapt to sea level rise.

Orlando and Atlanta are also projected to receive more than 250,000 climate migrants through 2100. Phoenix and Las Vegas, both of which are already struggling to keep up with water and electricity demand, could also see an influx of people.

The biggest population-losing cities are not that surprising: New Orleans and Miami.

In Florida, the area from West Palm Beach south to Miami is projected to lose as many as 2.5 million people by 2100 due to sea level rise-related flooding, the study found. Some 2 million people could still flee the area even if climate change adaptation measures are undertaken, such as building sea walls, raising coastal roads to prevent them from flooding regularly, keeping salt water from entering water supplies, and other projects.

Nine states could see a net population loss, including Massachusetts, South Carolina, California, Virginia, New Jersey, Louisiana, and Florida.

The study, by Matt Hauer of the University of Georgia, claims to be the first to show how climate change may reshape where people live across the country. Most sea level rise studies focus on the risk to coastal residents, but this one goes significantly further by trying to determine the inland areas that may be placed under strain when climate migrants move in droves.

"We typically think about sea level rise as a coastal issue, but if people are forced to move because their houses become inundated, the migration could affect many landlocked communities as well," Hauer said in an email.

Hauer said he was surprised that many people are projected to move from coastal areas hit hard by sea level rise to other more resilient coastal regions — such as from one part of coastal California to another, at least according to the modeling he used for the study.

Globally, climate migrants from sea level rise alone could reach as many as 180 million, the study found. When including other climate change impacts, such as drought, more severe storms, and longer-lasting and hotter heat waves, entire regions of the world, such as the Middle East and North Africa, may be virtually uninhabitable as soon as the end of the current century.

Image: Hauer, Nature Climate change 2017.

According to the new study, only wealthy households with incomes of greater than $100,000 will remain in coastal areas because they can afford to take adaptive measures to prepare for sea level rise. However, it could also be argued that poorer residents won't be able to migrate because they can't afford to resettle.

Both the study itself and an accompanying article in Nature Climate Change show that there are many uncertainties involved with trying to determine where climate migrants will go once they are displaced from coastal areas. For example, it's not clear where the best economic opportunities will be in 30 to 50 years from now, which would affect migration patterns.