In Senate reelection bid, Heidi Heitkamp, a lonely North Dakota Democrat, charts her own path

DICKINSON, N.D. — For Heidi Heitkamp, a centrist Democrat and one of the Senate’s most vulnerable incumbents, the path to reelection on a recent Saturday morning ran between a car full of clowns in rainbow wigs and polka dot suits and a gigantic monster truck packed with a boisterous group of heckling Trump supporters.

“Make America Great Again! Make America Great Again!” they chanted over and over as the truck’s driver revved his engine, effectively drowning out the senator’s conversation with a voter.

Surveying the scene, clowns and all, Heitkamp smiled. “Average Saturday,” she joked.

The occasion was the annual Roughriders Day parade, one of the largest celebrations of what many here call “parade season” in North Dakota. The event, which coincides with the local rodeo, is considered a rite of passage for any serious politician — an annual test of physical endurance in a state where voters put a high value on being able to see and talk to their elected officials. The roughly 2-mile-long parade route stretches through the heart of this rural Western town, attracting thousands of people who stake out prime viewing spots well before dawn. Politicians who participate are expected to walk most — if not all — of the route, shaking hands, posing for photos and talking to voters.

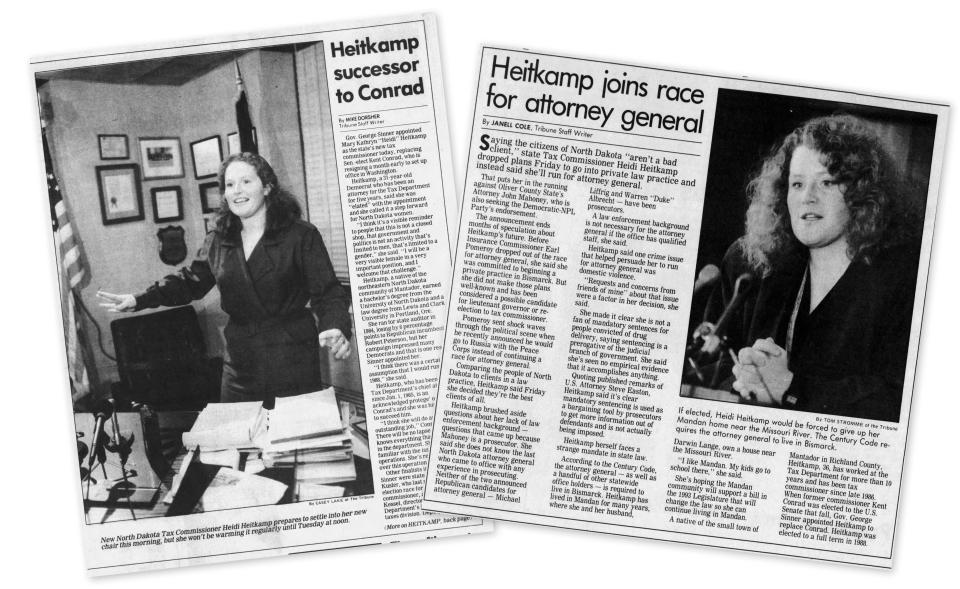

Heitkamp, a fixture of North Dakota politics for more than three decades, dating to her days as state tax commissioner in the 1980s and later as state attorney general, has been here many times before. It’s the kind of event where she’d earned her reputation as a politician who didn’t outwardly seem like a politician: a personable, no-nonsense candidate who the Associated Press recently likened to Marge Gunderson, the fictional heroine of the Coen brothers’ classic “Fargo” and the cinematic epitome of Midwest nice.

It was not an off-the-mark comparison. On the trail, Heitkamp, famous for her salt-of-the-earth demeanor and shock of wavy red hair, speaks with a distinct regional accent — a little Minnesota --with a splash of Chicago thrown in. She tends to be a hugger, a rumpled mom type so friendly and affectionate with those she’s speaking to that it’s sometimes hard to tell whether she already knows the person or just met them.

Stopping by a coffee shop before the parade, dressed in jeans and sneakers with her face free of makeup, the senator was finishing an iced coffee when a woman caught her eye.

“Stronger than battery acid, eh?” the woman said with a wink.

She was referring to Heitkamp’s recent campaign ad, which featured the senator, dressed in a mechanic’s jumpsuit, fiddling under the hood of an old pickup truck. Over the sound of a socket wrench at work, a narrator quoted Sen. Bob Corker — a moderate Republican from Tennessee — who once praised Heitkamp, his colleague on the Senate Banking Committee, as being “stronger than battery acid” during bill negotiations.

The ad concludes with Heitkamp yanking a battery out of the truck engine with her greasy gloves and declaring, “When it comes to fighting for North Dakota, I take battery acid as a compliment.” The spot, unveiled in May, had been playing nonstop on local television in recent weeks — going up against waves of attack ads run by her Republican opponent, Rep. Kevin Cramer — the state’s three-term congressman at large — and his allies, who have sought to portray her as a liberal stooge out of step with North Dakota voters.

In the coffee shop, Heitkamp laughed. “Do you know how many men have asked me to change their battery since that? I mean, I could,” she said. Among her myriad jobs as a kid growing up rural Mantador, population 64, was construction worker and dairy farm equipment repair person. She knows a thing or two about tools.

Somehow the conversation turned to the question of age. The woman told Heitkamp she was certain she was older than the senator, who is 62. When it turned out the woman was 58, Heitkamp was visibly shocked. “No s***? You don’t look a day older than 45,” she said earnestly. And then she grabbed the woman’s arm in an affectionate squeeze, as if the two had known each other for years, adding, “And I’m not just saying that because I want your vote.”

As Heitkamp walked out, the woman, who said she was a registered Republican but would not give her name, said simply, “I love her.”

It was the kind of interaction that encapsulates Heitkamp’s approach to winning a second term in ruby red North Dakota, where a Democrat, even one as conservative as she is, starts with an almost insurmountable disadvantage.

In a state President Trump won by nearly 36 points two years ago and where elected Democrats are scarce (the party holds just 22 of the 141 state legislative seats, and has been shut out of every statewide office except Heitkamp’s), the incumbent senator has tried to rise above the hardened political partisanship that has divided the rest of the country.

Using phases such as “sensible” and “trustworthy” — and the occasional “no bulls***” — Heitkamp presents herself as an honest-to-God, middle-of-the-road lawmaker who can, and has, worked with both sides to do right by her state and won’t be, as she puts it, “a rubber stamp for anybody.”

“One side is not always right,” Heitkamp said in an interview. “The left doesn’t always have it right. The right doesn’t always have it right.”

Her centrist pitch has been bolstered by her friendly relationship with Trump himself, who interviewed her for a job in his cabinet in late 2016 (she turned it down), and flew with her on Air Force One to North Dakota last year to tout their joint efforts to encourage the state’s booming energy industry.

At the event, held at a refinery in Mandan, a small town outside Bismarck where she has lived for more than thirty years, Trump invited Heitkamp on stage and shook her hand — ironically reaching around Cramer, who was not yet in the race, to do so. “Good woman,” he declared, a note of praise that many here have not forgotten even though he is now actively campaigning against her bid for reelection.

But more than politics, Heitkamp has tried to emphasize personality. She is self-deprecating to a fault, once marveling at how a “chubby” small-town girl like her made it to Washington. Speaking to voters, she presents herself as a person who is just like them; someone who hasn’t forgotten her modest roots. She tries to sway them into looking beyond their political party and voting for her because they actually like her.

“People here know me. Even if they don’t agree with me all the time, they know I fight for them,” she said. “I wake up every morning thinking about rural America. I’m not sure how many other people can say that and really mean it.”

It was a strategy that worked in 2012 when Heitkamp won her first term in the Senate by the narrowest of margins — 2,936 votes to be exact — defeating Rick Berg, a Republican congressman, to fill the seat being vacated by Sen. Kent Conrad, the longtime Democratic incumbent and mentor to Heitkamp, who was retiring after a quarter-century in office. The win shocked the political world in a place where most people — Democrats included — assumed Republicans would easily claim the seat given North Dakota’s surge to the right in recent years.

Six years later, Heitkamp faces perhaps steeper odds in a state that is even more conservative now. While she is no leader of the Democratic resistance against Trump — and has not been pressured to be by fellow Democrats at home or in Washington — she has been forced to walk a tightrope in her comments about the president.

On the campaign trail, Heitkamp pitches herself as both a partner to Trump — pointing out their work together on policy helped ease regulations on community banks and on energy — and a polite critic, more so lately. Among other things, she’s hit the president’s controversial trade war with China, which threatens North Dakota’s export-dependent soybean farmers and other interests in this heavily agricultural state. “There’s a lot of people here willing to say let the president work his magic,” she said, adding that she was not one of them.

(Last week, Trump, who initially suggested that farmers were “great patriots” who would be willing to make sacrifices in his trade wars, offered them a temporary $12 billion relief package, a bailout that has been criticized by farmers and members of both political parties, including Heitkamp.)

Cramer has disputed Heitkamp’s bipartisan credentials, linking her to party leaders like Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi. He has run ads reminding voters about her endorsement of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign and her support for abortion rights.

And in an attempt to challenge Heitkamp’s relationship with Trump, which has been so cozy that he publicly complained about it, the congressman has billed himself as someone who would support the president all the time — not just some of the time.

In April, Cramer, who has a reputation of making cringeworthy remarks, likened voting against legislation backed by Trump to cheating on one’s spouse. “I’ve heard her say, ‘Gee, I voted with him 55 percent of the time,’” Cramer said of Heitkamp. “Can you imagine going home and telling your wife, ‘I’ve been faithful to you 55 percent of the time?’ Are you kidding me? Being wrong half the time is not a good answer.”

While Cramer later dialed back his comments, saying his ultimate loyalty was to North Dakota, Heitkamp seized on his reluctance to publicly criticize the president on issues such as trade, suggesting he wants to “give away” the state’s Senate seat to Trump. “Can you imagine saying you want to vote 100 percent of the time with anyone?” she said.

Cramer’s seeming unwillingness to go against Trump even on trade and tariffs caused him to lose the backing of Americans for Prosperity, the influential policy and political donor group founded by the conservative Koch brothers which typically spends tens of millions of dollars to elect Republican candidates. The decision came weeks after the donor group ran a “thank you” ad praising Heitkamp for her efforts to boost community banks — a show of support that did not go unnoticed by Republicans in Washington.

There has been little public polling in the race, but a survey in June found Cramer had a narrow edge — 48 percent to Heitkamp’s 44 percent, according to Mason-Dixon, results that were within the margin of error.

Democrats need to hang on to Heitkamp’s seat if the party has any chance of regaining majority control of the U.S. Senate next year. The party needs to win two more seats in addition to defending the 26 other seats up for election, including in North Dakota. But Heitkamp downplayed the future of the party as a key issue in her race, though she did acknowledge what happens in North Dakota will have “national implications.”

“I think this race has everything to do with whether it’s possible in this kind of world to have moderates get elected,” she said. “I say to North Dakotans: If you want bipartisanship, you have to be bipartisan. … To me, good ideas don’t just come in blue or red. Good ideas come when you sit down and you actually bring ideas to the table. The question is, is there room any more in America for that kind of leadership?”

Asked if she thought there was, Heitkamp paused for a moment. “I don’t know,” she bluntly admitted. “I guess we’re going to find out.”

The first woman elected to the Senate from North Dakota, and one of the few to hold statewide office, Mary Kathryn “Heidi” Heitkamp came from humble beginnings. She grew up in Mantador, a sparsely populated community surrounded by corn and soybean fields in far southeastern North Dakota. It’s about an hour south of Fargo, where the local VFW club — which her father founded — is still the heart of town, serving as the de facto city hall, post office and local watering hole.

She was the middle child of seven kids — two boys and five girls, all born a year or less apart. Her father, a World War II veteran who didn’t graduate from high school, supported the family working seasonal jobs, including hauling fuel and doing construction work. He also worked as a janitor at the local school, where her mom served as the cook. The family was crammed into a small three-bedroom house. Her brothers shared a room, which also happened to be the laundry room, while the five girls shared another bedroom. Between them and members of the extended family who also lived in town, Heitkamp has joked, her family made up a good chunk of the town’s population.

When they were old enough, the kids went to work, taking odd jobs around town to help the family make ends meet. Still, Heitkamp describes an idyllic childhood, playing in the softball league her father founded and getting lost in books. When she was in sixth grade, she became obsessed with the television show “Perry Mason” and decided that she wanted to be a lawyer, a dream that her parents encouraged.

On the campaign trail, Heitkamp’s easygoing demeanor belies her achievements. While attending the University of North Dakota — paid for with scholarships and by working at a dairy farm — she landed two internships: one with Congress and another working for the state legislature, where she began to envision a future working in public policy. After earning a law degree from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Ore., in 1980, she briefly moved to Washington to work for the Environmental Protection Agency. She returned to North Dakota the following year, working on the staff of Kent Conrad, the state tax commissioner and future senator.

In 1984, impressed by her work ethic and policy acumen, Conrad encouraged her to run for state auditor. Heitkamp, who was only 28, initially refused. Though she was interested in politics, she saw herself as a behind-the-scenes person — “the people who would help make things work, not the person out front,” she said. But when she showed up and saw her name on a banner at the state convention, she realized she had been drafted. A few months later, she narrowly lost the race. “I thought, ‘Okay, I did it, and now I can go home, resume practicing law, and get married and start my family,’” she recalled.

But two years later, Conrad was elected to the U.S. Senate, and on his recommendation, Heitkamp was appointed by the governor to replace him as state tax commissioner. Then a newlywed — she had married Darwin Lange, a rural doctor — Heitkamp was barely 31. The appointment made her front-page news in the Bismarck Tribune, where Heitkamp, looking younger than her age, called her new job a step forward for North Dakota women. “It’s a visible reminder to people that this is not a closed shop, that government and politics is not an activity that’s limited to men,” she told the paper, vowing that she would be a “very visible female” in state government.

In 1992, she moved up the ladder — winning the first of her two terms as state attorney general, where she gained national attention for her leading role in helping negotiate the 1998 landmark settlement between the nation’s four top tobacco companies and 46 states over the recouping of tobacco-related health care costs.

In 2000, Heitkamp announced a run for governor — a race she narrowly led until the final weeks of the campaign, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Only 44 at the time, she had her right breast and surrounding lymph nodes removed a month before Election Day, but continued to campaign, citing a favorable prognosis from her doctor.

Though voters insisted her illness would not affect their vote, a subsequent whisper campaign questioning whether she would be able to balance her cancer treatments with public duties — or even live through her term if elected — surfaced as the race reached its conclusion. She lost by 11 points to Republican John Hoeven, a banking executive who was later elected to Senate, where he is now Heitkamp’s colleague.

It was a heartbreaking loss for Heitkamp, whose cancer has been in remission since. But she says she learned a lot — not only from losing the race but also from her health scare. “You can lose races and it’s not the end of the world. It will hurt, but there are other ways of being a good citizen,” she said. “It’s not always just about politics.”

Heitkamp thought her career in public life was over, and as someone who still describes her foray into politics as somewhat accidental, she was okay with it. She went home to her husband and two kids, Ali and Nathan, who were teenagers at the time. She became the director of a natural gas company, where she worked for more than a decade, and dabbled in occasional political efforts, including a ballot initiative directing the state on how it should spend the millions it received in the Big Tobacco payout.

When Conrad decided to retire from the Senate in 2012, he called his former protégé and encouraged her to run. Heitkamp wasn’t sure she wanted to. “I think people think that someone sits down and plots an entire political career, and some people do, but I’m not one of those people,” she said. But she entered the race and narrowly won, a Democrat defying the odds in a conservative state.

Six years later, she’s trying to buck the odds again, in a race that will test whether voters still have an appetite for politicians who govern from the middle. While Cramer has run ads depicting her as a wild-eyed liberal, Heitkamp has charted a largely centrist path, championed causes that are popular with her conservative constituents back home and often angered Democrats in Washington in the process.

In 2013, just weeks after she was sworn in, Heitkamp defied intense lobbying from fellow Democrats — including top members of President Barack Obama’s administration and former Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, who was critically injured in a 2011 shooting attack — and voted against legislation that would have expanded background checks on gun buyers. Her staunch resistance to other gun control legislation earned her an “A” rating in the past from the National Rifle Association, though this year the group has so far not issued a grade in the race.

And though Heitkamp publicly supported Obama, telling voters back home that she proudly voted for him, she bucked the Democratic president on some of his chief priorities, including climate change legislation. She joined with Republicans to fight increased regulation of natural gas, and broke with Obama to back two controversial oil pipeline projects — Keystone XL and Dakota Access — which she billed as crucial to energy independence and a source of jobs.

“You can oppose the road, but sometimes you need a road,” she said in an interview. “And sometimes you oppose a pipeline, but you need that pipeline. … We need energy infrastructure in this country, but maybe more importantly, there’s working people who need to be able to earn a living.” She praised Democrats for trying to tackle complex environmental issues, but she faulted her party for not always taking into consideration “the working class” whose jobs may be affected.

In her six years in Washington, Heitkamp has come to be considered such a reliable ally to Republicans that Trump tried a few times in the past year to convince her to switch parties, entreaties that she refused. But she has continued to be friendly to Trump at key moments. She pointed out in a recent campaign spot that she has voted “over half the time with President Trump,” including on White House-backed policies and nominations. “And that made a lot of people in Washington mad,” she says in the ad.

She isn’t wrong. Heitkamp angered her party when she and two other Democrats — Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Joe Donnelly of Indiana — broke ranks last year to vote for Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s first Supreme Court pick. More recently, she was one of seven Democrats who voted to confirm Mike Pompeo as Trump’s secretary of state, and one of six who voted for Gina Haspel to be CIA director. When Trump signed the bill easing regulations on community banks that he had championed with Heitkamp, she stood at his side — a photo op that Cramer publicly complained about.

In an interview with the Washington Post, Cramer called it “obscene” that Heitkamp, his opponent, had gotten prime real estate next to the president in the photo, and questioned why Trump, who had talked him into jumping into the race for Senate, was being so easy on her. “I do think there’s a little difference in that she’s a woman,” Cramer told the Post. “That’s probably part of it — that she’s a, you know, a female. He doesn’t want to be that aggressive, maybe. I don’t know.”

A few days later, Trump announced that he would campaign for Cramer in North Dakota. And in late June, he returned to the state where he had once praised Heitkamp as a “good woman” and told voters she could not be trusted.

The rally was held just hours after Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy announced he would retire. Overlooking Heitkamp’s vote to confirm Gorsuch, Trump attacked her as an ally of Schumer and Pelosi. “Heidi will vote no to any pick we make for the Supreme Court. She will be told to do so,” Trump declared.

But less than 24 hours later, Heitkamp was back at the White House at Trump’s invitation, called down to Pennsylvania Avenue as the president began to solicit advice about his Supreme Court pick. Outside the White House gate, Heitkamp filmed a video — which she posted on Twitter — calling attention to the meeting and saying she was always happy to meet with the president and “to advocate for North Dakota.”

In an interview, she dismissed Trump’s attacks — which he has not repeated since his appearance with Cramer last month — as purely “political talk.” “He’s not standing up there as president; he’s standing up there as leader of the party,” she said. “He’s got his memo from the Cramer campaign saying, ‘These are the buzzwords we want you to use.’ That shouldn’t surprise anyone.”

But Heitkamp has broken with Trump on several big issues, taking positions that Cramer is now trying to use against her. He has mentioned opposition to Republican efforts to roll back the Affordable Care Act. And last winter, she opposed Republican tax cuts —Trump’s singular legislative achievement and the main talking point for GOP incumbents ahead of the Election Day. She has defended the vote by saying she did not want to expand the country’s growing national debt.

In a recent ad, Cramer went after Heitkamp for her tax cut vote, while acknowledging her personal appeal to voters. “We all like Heidi,” he declared. “But she was wrong to oppose this tax cut.”

Most of the state is Republican territory. But Heitkamp’s appearance in Dickinson took her to the conservative heart of North Dakota — one of the most strongly Republican areas in the entire state, where Trump remains exceedingly popular.

In fact, the parade’s theme that day was borrowed directly from the president himself: “Make America Great.” The phrase was plastered on dozens of floats and vehicles carrying parade participants. And right there in the middle of it was Heitkamp, who was walking so quickly and enthusiastically that her own entourage struggled to keep up.

For nearly 2 miles, the Democratic senator, who has an arthritic knee, outmarched everyone in her entourage, including her staff of 20-somethings. Many of them scrambled to keep up with their 62-year-old boss as she zigged and zagged across the road to shake hands with spectators.

The one-term senator wore a blue and gray shirt that read “Heidi for North Dakota” on the front, but no introductions were necessary. Even in this strongly Republican town, people were crying out her name — “Heidi!” — and waving her down for selfies, including a man wearing a Trump shirt who grabbed her in a tight embrace. “Keep doing what you’re doing,” he told her. It was a moment you rarely see in a nation so bitterly divided on partisan lines.

Near the end of the parade, Heitkamp came across a young woman holding a baby who was barely 2 months old. She was a foster mother who had opened up her home to kids who needed help. Clearly moved, the senator stopped to talk to her, wanting to know more. But their conversation was soon drowned out by the revving engine of the monster truck, whose occupants began chanting, “Trump! Cramer! Trump! Cramer!”

The truck grew closer. Her aides protectively herded her back toward her entourage.

North Dakota is different kind of place, Heitkamp said that morning. It may be a conservative state that is only growing more strongly Republican electorally, but she still believes that people here could look beyond party politics at the ballot box.

North Dakotans, she said, “are more independent than what you think. If they weren’t, I wouldn’t be here.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Former Trump official: No one ‘minding the store’ at White House on cyberthreats

Voting rights advocates wary of Kavanaugh’s nomination to Supreme Court

No experience necessary? Trump and the future of the celebrity candidate

Progressive Dems try to catch some of Ocasio-Cortez’s lightning in a bottle

Photos: Former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort’s trial in Alexandria, Va.