Under Sessions, who will keep tabs on the cops?

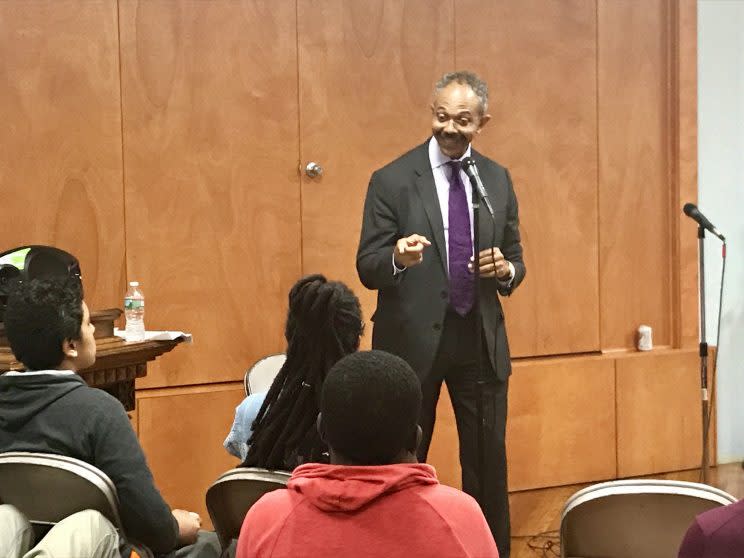

NEWARK, N.J. — Despite the torrential rain outside, Newark residents filed into St. Stephen’s Church, in the heart of the city’s multiethnic Ironbound neighborhood, last Monday night for a meeting with Peter Harvey, the federal monitor assigned to oversee the implementation of court-ordered reforms by the Newark Police Department.

Newark was one of 14 police departments to enter into consent decrees with the Department of Justice during the Obama administration as a result of investigations into unconstitutional practices by police in cities across the country. Now, that department is led by an outspoken opponent of police oversight: Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Law-enforcement agencies, local judicial systems and civil-rights advocates are all looking for signs of how the change in leadership will play out in cities under consent decrees — and in those without them as well.

In late March, Sessions issued a memo ordering a broad review of all the department’s existing investigations, training, compliance reviews and other engagements with local law enforcement agencies — including “existing or contemplated consent decrees” — to ensure that they do not undermine the Trump administration’s law and order agenda.

Harvey had been slated to discuss the findings of his first quarterly report on the Newark department’s progress. But he was met with repeated accounts of abuses at the hands of the department he was monitoring — including threats, harassment and physical assault against civilians.

“He kicked the door in, as if he was my personal enemy,” said Julio Sancho, describing an encounter with a Newark police officer who’d become aggressive after Sancho, an Ecuadorian immigrant who has lived in Newark for 17 years, questioned the officer about why he was ticketing cars across the street. With the help of an English translator, Sancho described in Spanish how the officer proceeded to physically assault him, pepper-spraying his children—the youngest of whom is 4 years old—as they yelled for him to stop.

“My children are traumatized,” said Sancho’s wife, Gloria Solano, becoming choked up as she corroborated her husband’s account.

“I don’t feel safe being protected by the police,” said Erica Lizotte, who lives with her partner, Corey Ross, and their four children, ages 5 to 12, in the Hyatt Court projects. Though the public housing complex is the setting of most of the violent crime in the city’s East Ward — including a shootout in January that killed a 16-year-old boy and injured three other teens — Lizotte said, “I would feel safer being protected by people in my neighborhood than by police.”

“The conduct you’re describing is exactly why the Newark Police Department got put under a consent decree,” said Harvey, a former New Jersey attorney general. The consent decree was the result of a three-year investigation by the Justice Department’s civil rights division, which found rampant racial profiling, unlawful stops and searches, excessive use of force, and theft, among other unconstitutional patterns and practices, in the Newark Police Department.

Despite Sessions’ assertion in his March memo ordering the review that “It is not the responsibility of the federal government to manage non-federal law enforcement agencies,” police and city officials in Newark as well as several other jurisdictions under DOJ monitoring insist they are committed to following through on their court-ordered reforms — with or without the attorney general’s support.

In New Orleans, “the current attorney general’s comments on his department’s policies don’t impact our commitment to constitutional policing and ongoing reform,” Beau Tidwell, a New Orleans Police Department spokesman, told the New Orleans Advocate following the release of Sessions’ memo.

Jonathan Aronie, the lead monitor for NOPD’s consent decree, agreed. “The consent decree is in place,” he stated at the time. “There are no changes to it.”

“I do think [the Newark police] are committed, but frankly they also have no choice,” said Dianna Houenou, policy counsel for the ACLU of New Jersey, pointing out that once a consent decree is put into effect by a federal district court, it becomes legally binding.

“Ultimately the monitor is independent and reports to the judge,” said Vanita Gupta, who ran the DOJ’s civil rights division from 2014 until President Obama left office. “The hope is that even without as rigorous Justice Department engagement, there will still be really robust enforcement.”

That’s why, Gupta said, choosing a monitor — a process now underway in Baltimore, which came under DOJ scrutiny after Freddie Gray died from injuries sustained in the back of a police van — is so important.

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson said police reforms would continue there as well, though perhaps with less stringent oversight from the DOJ. In its latest progress report, released earlier this month, the Cleveland monitoring team found CPD to be noncompliant in almost half of its consent decree duties, including the creation of a Force Review Board and a requirement that officers clearly report the justification for all stops, searches and arrests. The department was deemed partially compliant on key reform areas like the development of new policies for lawful use of force and bias-free policing.

“The Monitoring team has run out of words to capture the depth and breadth of the progress that needs to be made to cure the current inability of Cleveland residents to have complaints about city employees fairly and fully addressed in a timely manner,” read one part of the latest report.

And in Albuquerque, police Chief Gordon Eden told the local CBS affiliate that the department would carry on with the reforms it has been implementing under a consent decree since 2014. Yet Shaun Willoughby, president of the Albuquerque Police Officers Association, said he hoped the review would provide an opportunity to discuss what he called “unrealistic expectations from a law-enforcement, boots-on-the-ground perspective.”

In his latest assessment, released in April, independent monitor James Ginger reported that the Albuquerque Police Department has made progress in some areas while demonstrating “deliberate non-compliance” in several others. And despite the police chief’s earlier statement, at a hearing to discuss the report last month, Ginger said he’s observed a “palpable shift” in the attitudes of department leaders, suggesting less serious commitment to reform.

“As far as I’m concerned, these consent decree processes are really about assuaging the concerns of white, middle class residents,” said David Correia, an anti-police violence activist and professor at the University of New Mexico. Correia attended the progress hearing last month and said the DOJ attorney there was “praising APD in ways they never had before,” despite the negative tone of Ginger’s report. The DOJ representative assured the meeting that there had been no instructions from Washington to soften enforcement.

Though Correia is careful not to suggest that “it doesn’t matter if Sessions calls off the dogs,” he questions whether consent decrees can provide a real solution to longstanding, systemic police problems.

“It doesn’t change the fear of the police in Albuquerque of homeless native people who are a particular target in Albuquerque — they’re just as scared of the cops as they’ve ever been,” he said. “But it stops the newspaper from writing editorials critical of police. It stops prominent white politicians from being critical of police.”

Correia said he thinks the best things to come out of DOJ investigations are not the reforms but the reports detailing the systemic abuses and unlawful behavior. The consent decree process, he said, is “almost like a baptism where you come out of it looking squeaky clean despite the fact that no real substantive changes are made.”

One recent study on the effectiveness of consent decrees suggests the money saved by preventing future lawsuits over police violence and other misconduct is worth the steep costs most cities must incur to comply with most consent decrees. However, other surveys indicate that deeply rooted problems often linger well after the Justice Department has left town.

Last week, the independent monitor overseeing Seattle’s reforms released a report declaring that the department had been in initial compliance with all of its court ordered reforms since 2012, including new policies on use of force, stop-and-frisk, and bias-free policing, and could now petition the judge to find the city in full compliance of its consent decree.

The same day the Seattle monitor released that glowing report, two white Seattle police officers shot and killed Charleena Lyles, a pregnant black mother of four, after she’d called to report an attempted burglary at her apartment. The officers said that Lyles, who reportedly suffered from mental health problems, was wielding a knife when they opened fire on her in her home.

*****

A spokesperson for the Justice Department in New Jersey declined to comment on whether they’ve received any guidance from Washington to ease off enforcing Newark’s consent decree during the review.

Among the department’s handful of first quarter achievements was the relocation of its internal affairs unit to a nonpolice facility, intended to make citizens feel more comfortable filing complaints about officer conduct. However, according to Harvey’s report, while “NPD has begun to revise its internal affairs policies and procedures,” the department has yet to provide either a revised internal affairs policy or new training materials, which must be approved by both the independent monitor and the Justice Department as part of the consent decree.

Still, at Monday’s meeting, Harvey insisted that the Newark residents should report misconduct to the internal affairs unit, comparing it to a leaky faucet that must be tested to determine whether it’s fixed. But Harvey discovered that the relocation had made little impact on the department’s longstanding practice of responding to civilian complaints with ambivalence, hostility, and even retaliation.

While one resident said many in her neighborhood choose not to report officers for fear of retaliation, Corey Ross said he’s gone to the new internal affairs unit a number of times already with complaints about officer misconduct, only to have those fears reaffirmed.

About a month ago, Ross said two officers showed up at his front door in the middle of the night after he filed a report against them earlier that day.

“You made a report against me!” Ross yelled, re-enacting the angry officer’s arrival by banging on the chair in front of him.

“When I say he was beat up by the police, he was beat up by the police,” Ross’s partner, Erica Lizotte, said, confirming the incident. “My kids and the neighbors kids were in the hallway screaming at the police officers to get off of him.”

Lizotte said they’ve since returned to internal affairs three times to report the retaliatory attack “and nothing has been done.”

Though seemingly shocked that such practices were continuing, Harvey urged everyone to be patient and to continue to report these experiences to internal affairs.

“They are making progress,” he said, reminding the group that the consent decree will be implemented over five years. “This kind of change that we’re talking about doesn’t happen overnight.”

But, Ross wanted to know, “how do we protect ourselves when we make reports against individual officers, to ensure our safety as human beings against retaliation by police officers while change is being implemented?” Harvey didn’t really have an answer.

*****

According to this report, the Justice Department’s civil rights division has investigated a total of 69 police departments for patterns and practices of unconstitutional conduct since it was first given authority to do so by Congress in 1994, following the riots sparked by a video of Los Angeles police beating Rodney King two years before.

Twenty-four of those investigations were launched during the Obama administration, many of them prompted by high profile police killings—like those of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., Freddie Gray in Baltimore, and Laquan McDonald in Chicago—that, much like the King beating, caused long-simmering tensions to boil over into civil unrest.

But while Obama’s Justice Department may have been more committed than any of its predecessors to imposing police reform, such incidents have continued, raising questions about future reform in cities that have not already committed to consent decrees. That includes places like Minneapolis, where recently released video footage has renewed outrage over a police officer’s acquittal in last year’s shooting death of Philando Castile, and other cities where such incidents have yet to become the subject of a viral video.

While a federal judge in Baltimore rebuked Sessions’ request to delay approval of the consent decree negotiated by the DOJ and city officials before Obama left office, the new attorney general’s opposition to police oversight seems to be having an effect in Chicago, where Mayor Rahm Emanuel backed off his previous promise to sign a consent decree with then-Attorney General Loretta Lynch. Emanuel is opting instead to work with the DOJ on an agreement to implement reforms without court oversight.

Gupta, who called the move by Emanuel “woefully insufficient,” explained that “there’s a reason” only 14 of the two dozen investigations of local police departments conducted by the division since 2009 have resulted in consent decrees.

“The Justice Department never went into a jurisdiction and conducted a civil rights investigation based on one specific incident,” Gupta told Yahoo News. “The civil rights division specifically gets involved … in cases where the erosion in community-police trust was so severe that, usually, police departments were at a crisis point.”

“Chicago was that kind of place,” she said.

Emanuel insisted last week he is no less committed to following through on his promise for reform. But Gupta says the slow pace and high cost of implementing mandatory reforms in Newark — whose population is a 10th the size of Chicago’s — offers an illustration of why “consent decrees are necessary … in jurisdictions where the deficiencies were so longstanding that it really would require significant time, investment and resources to be able to build back up a constitutional police department.”

Enacting departmental change is hard under any circumstances, said Dianna Houenou, policy counsel for the ACLU of New Jersey. “So without the DOJ enforcement it’s really going to put a damper on the progress that’s made, and [it’s] also going to be really disheartening for the public to know that the top law enforcement official in the country doesn’t think there’s an issue with police brutality, with discriminatory policing and with theft by officers.”

“It’s really hard to continue trusting in a criminal justice system and law enforcement officers if you have no assurances that the people who are supposed to protect your constitutional rights — especially at the federal level — are going to do so,” she said.

*****

Even if consent decrees fall short of completely reshaping the way local police departments approach law enforcement, the simple requirement that officers be trained to treat civilians like human beings can at least lay the groundwork for a more positive relationship between police and the people they serve.

Julio Sancho has experienced the difference firsthand. Sancho has had his fair share of encounters with both the Newark and New Jersey State police, who came under their own consent decree in 1999 after a Justice Department investigation into pervasive racial profiling in traffic stops.

The latter decree, which was dissolved in 2009, hasn’t stopped Sancho from getting pulled over regularly. But while his encounters with Newark officers have been abrasive, tense, and completely devoid of pleasantries, Sancho said the state troopers are “a little more respectful,” always making the effort to ask how he’s doing before requesting to see his ID.

“They treated me with respect,” Sancho said, through the translator. And as a result, he declared, “I have respect for state police.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: