Is sexism what happened to Hillary?

I took my kids to New York for last November’s election, so they could experience the hum of a newsroom and help color in Yahoo’s giant red-and-blue map with chalk. The outcome devastated my 8-year-old daughter. She was excited by the idea of a Hillary Clinton presidency and had never understood why I was less so.

On the train back to Washington the next day, as I sat writing my column, I noticed that she had left off with whatever Disney show she’d been watching and was staring numbly at the passing scenery.

I leaned toward her and said quietly, “You’ll see a woman president in your lifetime. I promise.”

She looked up at me totally unsurprised, as if I had read her thoughts.

“In your lifetime, too?” she asked.

It’s hard for me to relive that exchange, even now. There was so much wrapped up in that question — not least her doubts about whether the country could ever be ready for her own limitless ambition, and how long it might take for us to really get there.

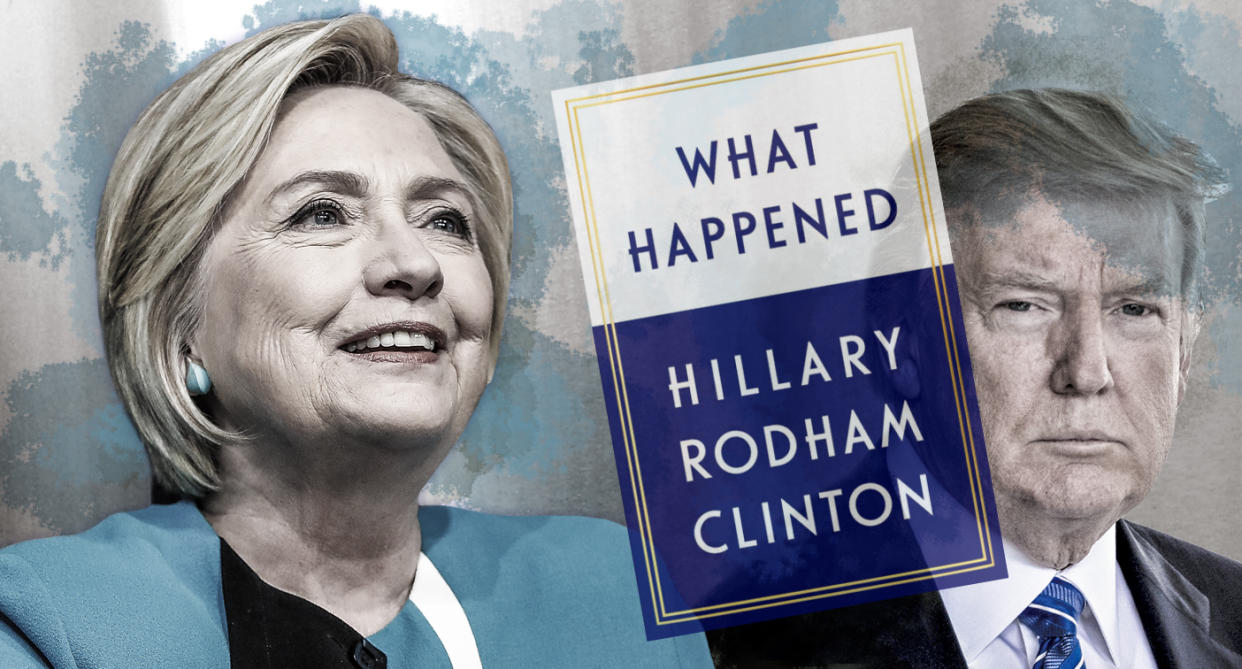

That same question runs like a treacherous current through Clinton’s much-anticipated campaign memoir, which I read this week. In general, I detest the entire genre of political memoirs, which are almost always hopelessly banal tracts published for the purpose of getting their nominal authors on TV. I expected nothing less from Clinton, who has written her share of the same.

In fact, “What Happened” is more raw and therapeutic than that. I agree with my colleague Jennifer Senior, who reviewed the book favorably for the New York Times, that this may be as close to the real Hillary as any of us are ever going to get.

As others have noted, Clinton blames a lot of other people for her loss. As ever, she is really good at declaratively stating that she takes responsibility for things that go wrong, but she doesn’t get what it actually means to take responsibility for things that go wrong.

Invariably, at an interval of what feels like every two pages, Clinton’s momentary mea culpas are followed by a “but,” and then by an explanation of why someone else — the media, the FBI, the Russians, the voters — was really at fault.

Perhaps the most consistent lament that runs through all of this, though, aside from Clinton’s inexhaustible contempt for the president who beat her, has to do with sexism embedded in the electorate and in the media, which Clinton clearly sees as the one towering obstacle she couldn’t shove aside.

“I suspect that for many of us — more than we might think — it feels somehow off to picture a woman sitting in the Oval Office or the Situation Room,” Clinton writes at one point.

And in another blunt passage: “Again, I wonder what it is about me that mystifies people, when there are so many men in politics who are far less known, scrutinized, interviewed, photographed, and tested. Yet they’re asked so much less frequently to open up, reveal themselves, prove that they’re real.”

Clinton can — and does — point to plenty of evidence to suggest that attitudes toward women skewed the election against her. Start with the fact that the winner was a pretty blatant misogynist who incessantly mocked women for their appearances and who was caught on tape boasting about his forcible advances on them.

According to data from Pew Research, Trump bested Clinton by 12 points among men, which was among the largest margins in the last 50 years. Among white voters without a college degree, Clinton lost by an astounding 39 points.

But it’s also true that a lot of recent Democratic candidates, all of them men, performed only incrementally better among these groups. And as Clinton herself notes, she also lost among white women, which at least complicates the gender argument.

To the extent that Clinton or some of her supporters see sexism as the principal answer here, then I think maybe they’re asking the wrong question. The relevant issue isn’t really whether gender matters in politics or in the society generally (it clearly does), but rather whether it’s the thing that matters most.

This is difficult for a guy to write about — I understand that. I’ll never have the personal experience with sexism that Clinton or other women in politics do. That’s just the peril of trying to understand politics from one’s own, limited perspective, which is what I’m charged to do.

History is instructive, however, when it comes to tracing the arc of systemic prejudices. I wrote about this at some length in 2008, when a lot of commentators were saying that Barack Obama couldn’t possibly win over enough working-class white voters to make him president.

When Al Smith ran for president in 1928, Catholicism was a defining (and ultimately disqualifying) trait in American politics; he was the Catholic candidate, and he lost. By the time John Kennedy ran three decades later, being Catholic was still a factor, but only a factor. Kennedy was a candidate who happened to be Catholic, and that was a different thing.

When Jesse Jackson ran in 1984 and again in 1988, he was widely viewed as the black candidate for president, and his failure was a foregone conclusion. But the door Jackson kicked ajar swung open wider for Obama 20 years later, when race was still an issue, regrettably, but no longer a defining one.

The same is true, I think, for being a woman. The congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Pat Schroeder were considered almost novelties when they ran for president (and, as Clinton notes, Schroeder was treated as a joke when she displayed the temerity to cry publicly). But Clinton entered the 2016 primaries as the establishment candidate and the overwhelming favorite, not just the female one.

Gender, while always an added challenge, never defined Clinton’s candidacy. And on the list of challenges that made Clinton a less than ideal candidate — her age, her perceived entitlement, her family history of scandal, her limited skill as a persuader — the fact that she was a woman probably hovered somewhere near the bottom.

In fact, you could make a reasonable case that, just as race actually helped Obama by giving white voters a chance to feel they were turning the page on an ugly historical chapter, gender probably benefited Clinton to some degree, too.

A lot of women who weren’t so excited by her personally were nonetheless inspired to support her candidacy anyway, because of the change she symbolized. That passion, more than anything else, probably enabled her to hold off Bernie Sanders’s ideological insurgency in the primaries.

I raise all of this, and the fury I know it will provoke among some readers, not because Clinton isn’t entitled to take away her own lessons from the 2016 election, but because I think it’s critical for Americans — and especially girls like my daughter — to get those lessons right.

And the right lesson, near as I can tell, is that if a woman can run as the overwhelming favorite of a major party, and win the nomination, and then go on to win the popular vote, then being a woman at the highest level in American politics isn’t a deal breaker anymore, or even a notable disadvantage. It’s just something else to factor in.

For Clinton, the totality of those factors was too much to overcome. But if she wasn’t the right woman for the moment, she has made it all that less remarkable for another woman to run and win.

In my lifetime, too?

The answer, I feel sure, is yes.