Showing up to school was hard amid COVID. Why aren’t kids (or teachers) returning to class?

ALEXANDRIA, Va. – On a drizzly, blustery morning in late April, elementary school Principal Jasibi Crews helped students exit their cars, heavy-duty umbrella in hand. Most of the school’s students live nearby and can walk to campus, but given the weather, many had to be dropped off.

Crews worried her school’s attendance would take a hit because of the conditions, and by the time she returned to her computer, her inbox confirmed her concerns. One grandma cited the downpour and concerns about a fever. Others said they didn’t have a car.

Soon after that, Crews found herself dealing with another problem. Several teachers were out for the day, and one class still didn’t have a substitute in place. All of the usual backups – coaches, specialists, other support staff – were either already filling in for other duties or out themselves. As the principal sorted through emails notifying the school of kids’ absences, she fired up her walkie-talkie to troubleshoot staffing needs. It wasn’t yet 8:30 a.m.

Student attendance nationwide is nowhere close to pre-pandemic levels amid parents’ ongoing concerns about students’ health, shifting mindsets about the importance of classroom time and the often-overwhelming expectations of school. Teachers and other staff are in short supply too, further threatening to disrupt kids’ academic progress.

What’s specifically alarming educators are the high rates of students missing vast stretches of their learning time – a month, two months, even half of the school year. Chronic absenteeism – which is generally defined as missing 10% or more of the school year – has continued to dog campuses despite the full-time return to learning in person.

After COVID-19, kids still missing classes

Chronic absenteeism can significantly reduce a child’s academic performance and odds of graduation. Federal law requires schools to publish detailed chronic absenteeism data annually, and most states have policies that hold districts accountable for addressing it.

But since the pandemic hit, the problem has reached new proportions, despite the widespread return to classrooms and standard school routines. The number of students who were chronically absent last spring was double what it was before COVID-19 – 16 million up from 8 million, according to one estimate.

National data for this year isn’t yet available. But statistics out of Connecticut – the only state to publish chronic absenteeism numbers monthly during the pandemic – show little improvement in attendance. Last school year, the state’s students had an average chronic absenteeism rate of 23.7%. As of April 2023, it was 21.8%. California’s rate climbed from about 12% to 30% from 2018-19 to 2021-22. Ohio experienced a jump from roughly 17% to 30%. Mississippi has seen the highest chronic absenteeism rates ever.

Why are kids missing so much school?

Families are still in a COVID-19 mindset. The first few years of the pandemic disoriented parents, with constantly evolving policies on what to do when their children said they were sick or had any sign of illness. Especially in the beginning, the guidance was to take extreme caution – to keep kids home even if they were feeling well but had potentially been exposed to the virus.

That mindset has stuck, educators said. “When we first came back to school they were pretty strict about ‘If you’re sick, stay home,’” said Lisa Cay, a veteran third grade teacher at Sleepy Hollow Elementary in Falls Church, Virginia, who in the fall said three of her 20 students were absent on any given day.

Widespread confusion remains over the best practices in the event a kid has the sniffles or a stomachache, said Hedy Chang, founder and executive director of Attendance Works, a national advocacy organization.

Especially in communities hit hardest by COVID, the everchanging guidance prompted intense anxiety about illness. “Communities that were frontline workers are also extra careful because they have experienced a lot of trauma and death,” Chang said.

Compounding these challenges are the varying notions among families of school’s role in a child’s life, and by extension, the importance of attendance.

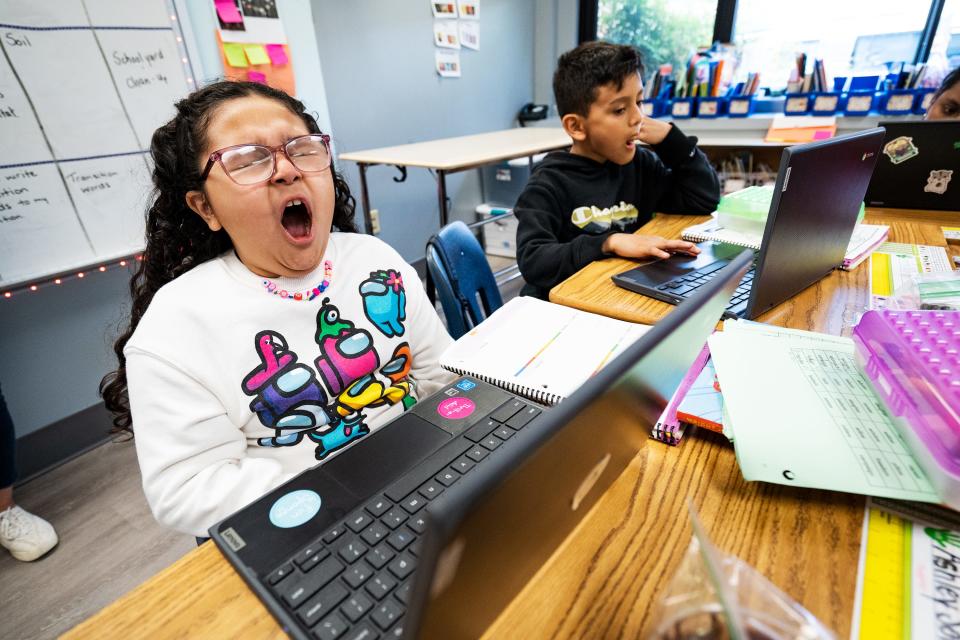

Third grader Ashley Soto, 8, rarely logged into online classes during the early days of pandemic, and although her attendance is better this year, she continues to miss school. Her mother, Maria Marenco Martinez, works cleaning homes and also has an 18-month-old and a teenager.

“My mom, she kind of sleeps sometimes – but it’s not her fault,” said Ashley, who attends school where Crews is principal. “She has to take care of three children at a time.” Ashley’s mom said she tries her best as a single parent to juggle everything, and that her three children constantly bring germs home and get each other sick.

Sleepy Hollow, in Falls Church, dug into its attendance data earlier this year. One trend the school discovered: Pronounced absenteeism on Mondays, a day many of the school’s parents – including those working in the restaurant industry – are off. “So they’re also home, and then it’s a day that they get to spend with their kids,” said Timothy Scesney, Sleepy Hollow’s assistant principal.

Health concerns and years of irregular school routines are evident at the elementary level, according to Chang. The Connecticut data, for example, show attendance has improved least – and in some cases worsened – among younger children and more among adolescents.

“Kids in the early grades, their attendance is affected both by what’s happening with them and what’s happening with their parents. If your parent’s car breaks down, if your parent has work, the kid may not get (to school),” Chang said. While absenteeism was always worst in the early grades, “the levels now are even more elevated.”

Long days harder for young kids

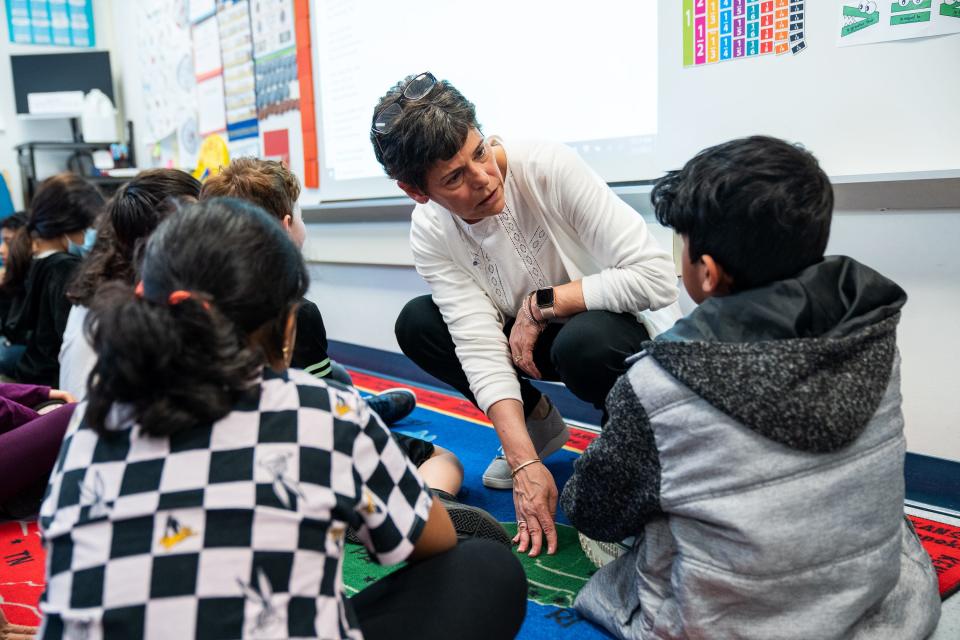

Alexandria’s Cora Kelly School for Math, Science and Technology, where Crews is principal, is doing everything it can to boost attendance.

Staff visit kids’ homes and host morning coffee get-togethers for caregivers. The school gave out alarm clocks to help kids wake up – inconsistent sleeping habits are another big problem – and thermometers so parents can check if a child who says they’re not feeling well is truly too sick to come to school.

Crews frequently reminds parents that if they’re not sure whether their child is healthy enough to attend, they can bring them in to see the school nurse. The school website features a prominent checklist to help sort out whether a kid really needs to stay home.

But according to Crews and other educators, kids’ diminished endurance has made it extra tricky to bring the numbers up.

“The hardest part of returning from the pandemic,” she said, “is stamina, getting up in the morning, getting back into the routine of coming to school.”

For the third graders in Virginia, this is their first full school year ever in a K-12 classroom. The pandemic hit in the middle of kindergarten. Virginia’s schools stayed remote for longer than most. During the 2020-21 school year – the second to have been affected by the pandemic, only 5% of Virginia students were in districts that offered “very high” levels of in-person instruction, according to a data brief.

“The other thing I think is so hard is when young kids have anxiety, what do they do? They have stomachaches,” Chang said. (Monday also tends to be a day people can feel extra anxious because of the return to the school or work week, which Sleepy Hollow’s Scesney theorizes is another reason for the school’s heightened absenteeism that day.)

Teachers also missing school days

Schools also have struggled more than ever to fill openings, regularly dealing with too few candidates for an open position to cost-of-living moves and health emergencies that necessitated reassigning and overloading existing personnel. Hard-to-fill jobs extend beyond the classroom to cafeteria workers, school psychologists and bus drivers. Missing drivers, in turn, can affect student attendance.

Some types of teachers – math, sciences, special education – were in short supply for years before the pandemic. COVID made those jobs, and thousands of others, impossible to fill, although the shortages hit districts unevenly. Urban districts, in particular, report an uptick in retirements compared with before the pandemic. One analysis of eight states found record-high departures.

Low pay and burnout – exacerbated by political pressures – have contributed to teachers leaving their jobs and to a decline in people pursuing the profession. According to a federal survey conducted last fall, nearly half of schools had at least one vacant position – about the same rate as when a similar survey was conducted last January. Schools in October had an average of two vacancies.

School districts in Connecticut and Florida are recruiting teachers from the Dominican Republic and Colombia to cover classes. Some states are tinkering with teacher licensing rules and creating new programs to attract people to teaching.

Cora Kelly has managed to fill all its positions but that isn’t the case a county over at Sleepy Hollow, where math coach Jessica Nelson found herself among the many doing something this year for which they weren’t hired. Last June, Nelson and the rest of the leadership got together – they deliberated professional development opportunities and new resources and how to shift teachers’ focus back to instruction and pedagogy after a volatile few years.

“We had this grand view of ‘We’re back, and we’re back 100%. And we’re not going to shut down. And they’re not going to tell us to go back,’” Nelson said.

But by August, a vacant fifth grade teaching position hadn’t been filled. As of June 2023, it still isn’t. A long-term substitute that the school hired to take over didn’t work out, and short-term substitutes are scarce nationwide.

So Nelson – who also serves in about half a dozen other roles, from the school’s testing coordinator to its summer programming manager – teaches the fifth grade class, with the help of the school’s literacy coach, Laura Bailey. Another teacher fills in for science.

The school has tried repeatedly to hire a teacher, but the demand for educators in the district – one of the country’s largest – far exceeds the supply.

No candidate they offered a job took them up on it.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Education dilemma: Why are kids (and teachers) missing so much school?