Something there is that doesn’t love a wall. Does poetry matter in the age of Trump?

In one of Aesop’s Fables, a kind woman encounters a snake that’s freezing to death. The animal begs the woman to care for it. The woman agrees. She gives the snake food and a blanket, and it recovers. Overjoyed, she hugs the snake, which bites her.

That tale inspired Al Wilson’s song “The Snake,” which caught the attention of a candidate for president. He repeatedly read the lyrics to the 1968 single on his campaign trail, posing it as a cautionary tale to warn of the dangers of foreigners entering the U.S.

That candidate became president.

While politicians are known for spinning tales, it may be surprising that President Trump, whose informal, simple speech patterns have fascinated linguists, chose to employ an allegorical tool at his rallies. But in 2016, the then-presidential-candidate read “The Snake” to his crowds several times. He spun the fable to warn of the perils of allowing Syrian refugees into the country and to argue for building a wall on the border with Mexico.

Trump knows what he’s doing. Song lyrics and poetry have gone hand in hand with politics for ages, and their effects on listeners can range from creating a sense of comfort to feeding national anxieties. As the White House rolled out its plans to reform America’s immigration system Wednesday, CNN correspondent Jim Acosta prefaced a question with a line from “The New Colossus,” the poem by Emma Lazarus inscribed in the Statue of Liberty. (“Give me your tired, your poor…”) Americans overwhelmed by a deluge of often-depressing political news have turned to poetry for relief, but at the same time, poets have turned to Trump, and his policies, as a source of (mostly negative) inspiration.

“We have voted and proven again/ we do not know one another. I am trying / so hard to understand this country, I tell you,” Alex Dimitrov wrote in “The Moon After Election Day.”

In “If They Should Come for Us,” Fatimah Asghar penned an ode to “my people” — a poem for characters such as “the sikh uncle at the airport/ who apologizes for the pat down/ the muslim man who abandons/ his car at the traffic light drops/ to his knees at the call of the azan” and “a muslim teenager/ snapback & high-tops gracing/ the subway platform.”

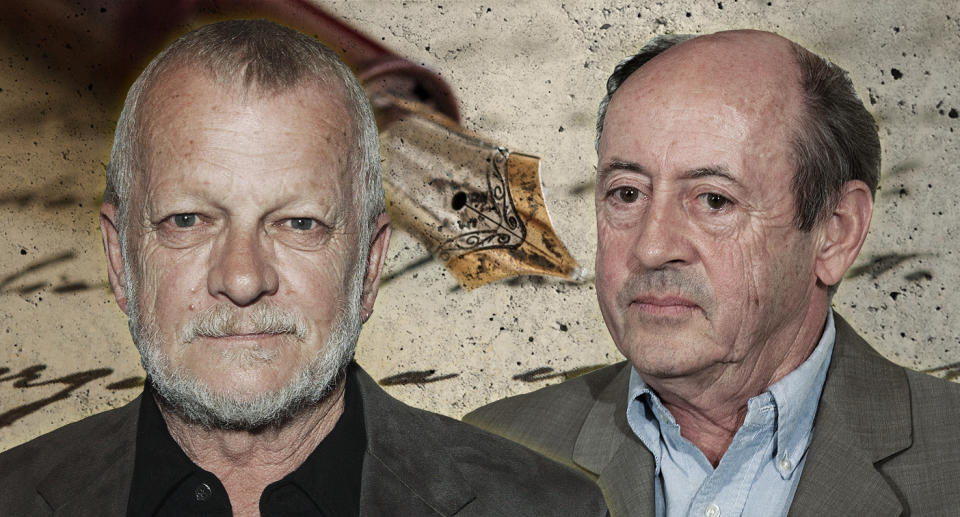

Former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky wrote in “Exile and Lightning” that people must stand against “charismatic indecency/ And sanctimonious greed. Falsehood/ Beyond shame.”

But can poetry — an art form often regarded as elite and esoteric — actually change anything in the era of Trump, who has cultivated an image as a populist?

“Truth be told, different things matter to different people,” said Amit Majmudar, the poet laureate of Ohio.

Majmudar, who edited the poetry anthology “Resistance, Rebellion, Life: 50 Poems Now,” a collection of poems intended to capture the climate after the 2016 election, freely admits that poetry is important only to a minuscule segment of the general population. A recent survey reports that only 7 percent of American adults read poetry, down by nearly half from a decade ago.

Those who write, though, have seemingly shot to the forefront of the national stage for their Trump protest poetry, similar to how poets have jumped to the front of national conversation during times of antiwar protests.

Even poets from the past, such as Robert Frost, have resurfaced in the news. The 20th-century poet wrote “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall. …/ Before I built a wall I’d ask to know/ What I was walling in or walling out” in “Mending Wall,” a poem that has been featured in several articles about Trump’s plan to construct a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

But Majmudar said that poetry and its reach haven’t changed. Rather, media coverage of poets has.

“Poets … are entering the media cycle because the media cycle is concerned with what they’re talking about,” Majmudar said. “Trump is the driver.”

Of the dozens of anthology submissions Majmudar received, not one was pro-Trump. Majmudar doesn’t find it surprising that the vast majority of poets are opposed to the president and/or his policies.

“We poets are the absolute antitheses of Trump,” Majmudar writes in the anthology’s introduction. “He lies. We speak the truth.”

For poets, writing is an act of resistance against politicians and the presidency. And for readers, poetry can be a comfort in the chaotic political climate.

“You can’t zoom through poetry; it forces you to slow down, think, concentrate, relish words and phrases. I now try to begin each day with a selection from George Herbert, Gerard Manley Hopkins, or R.S. Thomas,” author Philip Yancey wrote in the Washington Post.

Yancey’s musing — that poetry provides relief from a fast-paced world driven largely by the omnipresence of social media — has some scientific basis. Reading or writing poetry can affect a person’s health, according to Nicholas Mazza, dean emeritus and social work professor at Florida State University. Mazza, who studies the little-known field of “poetry therapy,” has found that poetry and literature have “definite” health benefits.

Writing poetry helps people feel as though they’ve gained control over difficult subjects and emotions, Mazza said. After tragic events such as the Columbine shooting or 9/11, there’s often a “national outpouring” of writing, which helps Americans cope with their grief and honor the dead and wounded.

“The writing is a safety valve,” Mazza said. “It really — sometimes it allows you an opportunity to express things you may not be able to express to another person otherwise.”

People seek therapeutic exercises like writing when they believe they have only poor choices, or no choices at all, Mazza said. The morning of Nov. 9, 2016, disbelief swept the nation, leaving many confused and anxious about what a Trump presidency could bring, and poets quickly penned their responses: “the man from TV/ is gonna be president/ he has no words/ & hair beyond simile/ you’re dead, America,” Danez Smith wrote the day following the election in “You’re Dead, America,” a poem that went viral.

Mazza studies songs and other works of literature besides poems. During the campaign and since the election, artists took advantage of Trump’s notoriety, alluding to him in lyrics. Rapper G-Eazy’s 2016 “FDT Pt. 2” includes the lyric “A Trump rally sounds like Hitler in Berlin,” and singer Fiona Apple’s 2017 release “Tiny Hands” criticizes the president’s comments about women to Billy Bush in the infamous Access Hollywood tape. (Prior to the presidential campaign most allusions to Trump simply referenced his wealth.)

Despite the outpouring of art about Trump, it’s not poetry or songs themselves that change things, Mazza said. Rather, it’s the individual experience of art that can help a person find solace.

“Poetry [existing alone] doesn’t make a difference,” Mazza said. “What I would try to point out is … [writing works by] instilling hope, restoring choice.”

In the political realm, poetry is nothing new. Before the Civil War, poets railed against slavery. In the 1960s, the Vietnam War. In the early 2000s, the Iraq War.

The Iraq War era brought one of the most high profile political gestures by a poet in recent years on a national stage. Former U.S. laureate Billy Collins publicly opposed the Iraq War during his second term as laureate, a move that put a spotlight on the often apolitical poet. Sitting laureates often remain mum on political issues, though their views are easily discerned from their work.

It started in 2003, when poet and publisher Sam Hamill rejected an invitation from first lady Laura Bush (a former librarian) to speak at a White House event celebrating the work of Emily Dickinson, Langston Hughes and Walt Whitman, during the buildup to the invasion of Iraq. The first lady cancelled the symposium out of fear that poets would turn it into a protest against the war. “It would be inappropriate to turn a literary event into a political forum,” her spokesperson said.

Hamill’s refusal inspired an online collection of antiwar poems from prominent poets.

Collins, who was invited to the event, joined dozens of other well-known writers in signing a petition urging the U.S. to avoid “an aggressive first strike against Iraq,” as war would “be unjust and result in the murder of innocents.”

“If political protest is urgent, I don’t think it needs to wait for an appropriate scene and setting and should be as disruptive as it wants to be,” Collins wrote to the Associated Press.

“I have tried to keep the West Wing and the East Wing of the White House as separate as possible because I support what Mrs. Bush has done for the causes of literacy and reading,” Collins wrote. “But as this country is being pushed into a violent confrontation, I find it increasingly difficult to maintain that separation.”

The title of poet laureate is one of the highest national honors for a poet. The laureate reports to the Library of Congress, under the legislative branch, and usually has little interaction with the executive branch and president. The full title is the U.S. Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. It comes with a $35,000 annual stipend, funded by a grant from Archer M. Huntington.

“Role is probably a good noun to use,” former laureate Pinsky said, describing the position. “People will sometimes mistakenly call it a job, and it’s just an honor, an honorary title.”

Each poet approaches the role differently, but some laureates have moved to Washington to be closer to the Library of Congress and to work with politicians. Newly named laureate Tracy K. Smith, who will assume the role in September, has vowed to work to make poetry more accessible to Americans, rather than focusing on politics.

But other poets have found themselves called to action. Trump’s presidency and policies have pushed poets to protest against his administration. In January, free expression organization PEN America hosted a literary protest at the New York Public Library, where poets read their work and then marched in protest to Trump Tower. At April’s March for Science in Washington, prominent poets read and taught poetry to help spotlight the human side of science. And several new anthologies have been published in response to the Trump presidency and current political climate.

“[Poetry is] essential to the whole democratic project,” Pinsky said. “It was traditionally part of the education of ruling classes, and in our country the ruling class is supposed to be the people, everybody.”

But does any of it matter on a national level?

Former U.S. laureate Robert Hass, Pinsky said, answers the question well. Simply, poetry takes time.

“Wordsworth had new ideas about nature: Thoreau read Wordsworth, Muir read Thoreau, Teddy Roosevelt read Muir, and we got a lot of national parks,” Hass wrote. “Took a century.”

More than a century after Roosevelt pushed for conservation programs and policies as president, Donald Trump takes the stage at a rally in Harrisburg, Penn., to mark his first 100 days in office. Though he did not employ an inaugural poet, the once-unlikely president pulls out a couple of sheets of paper. On them is “The Snake.” He asks the audience if they’ve heard it before, and if they want to hear it again. The crowd responds with roaring applause.

“I thought of it as having to do with our borders,” Trump says. “Here it is, ‘The Snake.’” The crowd quiets, and the president begins to read.

“‘I saved you,’ cried the woman,” Trump reads. “‘And you’ve bitten me, but why? You know your bite is poisonous and now I’m going to die.’ ’Oh shut up, silly woman,’ said the reptile with a grin.

“‘You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in.’”

The audience applauds, some of them stand, and the president tucks the poem inside his jacket to chants of “Build the wall.”

“Does that explain it, folks?” Trump asks of his plan to build the wall. “Does that explain it?”

Read more from Yahoo News: