Special Report: College Board faces rocky path after CEO pushes new vision for SAT

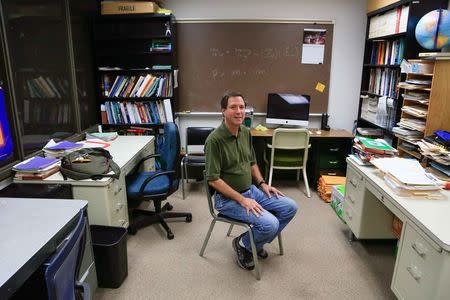

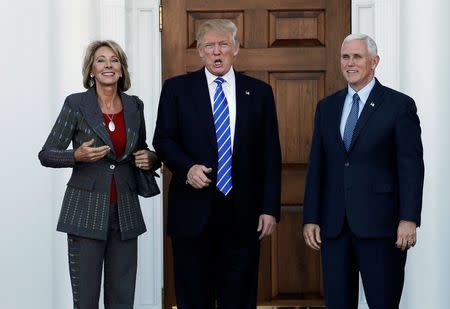

By Renee Dudley NEW YORK (Reuters) - Shortly after taking over the College Board in 2012, new CEO David Coleman circulated an internal memo laying out what he called a “beautiful vision.” It was his 7,800-word plan for transforming the organization’s signature product, the SAT college entrance exam. The path Coleman laid out was detailed, bold and idealistic - a reflection of his personality, say those who know him. Literary passages for the new SAT should be “memorable and often beautiful,” he wrote, and students should be able to take the test by computer. Finishing the redesign quickly was essential. If the overhaul were ready by March 2015, he wrote in a later email to senior employees, then the New York-based College Board could win new business and counter the most popular college entrance exam in America, the ACT. Perhaps the biggest change was the new test’s focus on the Common Core, the controversial set of learning standards that Coleman himself helped create. The new SAT, he wrote, would “show a striking alignment” to the standards, which set expectations for what American students from kindergarten through high school should learn to prepare for college or a career. The standards have been fully adopted by 42 states and the District of Columbia - and are changing how and what millions of children are taught. Redesigning the SAT to reflect the Common Core has solidified Coleman’s influence as one of the most powerful figures in education. He has emerged as “the arbiter of what America’s children should know and be able to do,” Diane Ravitch, former assistant secretary of education for President George H.W. Bush, wrote in her blog. But Coleman’s “beautiful vision” for remaking the exam soon met some harsh realities. Internal documents reviewed by Reuters show pitched battles over his timeline to create the new test and whether the push to meet the deadline could backfire. The documents, which include memos, emails and presentations, reveal persistent concerns that aligning the redesigned SAT with the Common Core would disadvantage students in states that rejected the standards or were slow to absorb them. The materials also indicate that Coleman’s own decisions delayed the organization’s effort to offer a digital version of the exam. Today, less than a year after the new SAT debuted, the College Board continues to struggle with the consequences of Coleman’s crash course to remake the SAT and its companion, the PSAT, a junior version of the exam. “It was a bad year, and I’m sorry,” Coleman said in September, at a conference of university admissions officers and high school counselors. “It is no good to have vision if you don’t deliver.” As Reuters reported in March, the College Board has struggled to stop cheating rings in Asia that exploit security weaknesses in the SAT and enable some students to gain unfair advantages on the exam. A massive security breach earlier this year exposed about 400 questions for upcoming SATs. And College Board officials went forward with the redesigned test even though they knew it was overloaded with wordy math questions, a problem that handicaps non-native English speakers and reinforces race and income disparities that Coleman has vowed to diminish. Coleman has subsequently pledged to streamline the SAT’s wordiest math questions and cut back on the reuse of tests, a practice that fuels cheating. The recent U.S. presidential election, however, could make the coming years even more challenging. President-elect Donald Trump has called the Common Core a “total disaster,” saying education must be controlled locally. He has promised to dismantle the Common Core and has selected an opponent of the standards, Betsy DeVos, to serve as secretary of education. Such high-level opposition could determine whether the course charted by Coleman helps or hurts the College Board. Several states already have backed away from the Common Core. And Ravitch, the former education official, worries that investing so much public trust in Coleman’s vision for learning and testing is risky. “All of these things were wrapped around the Common Core. That’s all unraveling,” Ravitch said in an interview. “If the SAT becomes woefully out of line with what’s happening in schools, then it’s less valuable.” Coleman, 47, declined requests to discuss his tenure. Asked what the Trump era and the selection of DeVos portend for the SAT and the College Board, Coleman sent Reuters a written statement: “Betsy DeVos is a remarkable citizen leader. She believes fiercely in our founding principles of liberty and equality of opportunity. We can’t wait to see what she does next as Secretary of Education.” Coleman appears to have the support of his organization’s Board of Trustees. Although none agreed to be interviewed for this article, the College Board released a short statement from Doug Christiansen, the chairman, lauding the CEO. “David Coleman and his team are leading the College Board through a time of remarkable, positive change in serving students and educators,” said Christiansen, who is also the dean of admissions at Vanderbilt University. Coleman’s agenda is spelled out in his internal plan to redesign the SAT and illuminated in thousands of pages of other internal documents that Reuters examined. Those documents, and interviews with people who know Coleman, provide a detailed look at his efforts to remake the College Board, an organization that has a profound impact on the lives of millions of students, parents and educators. RUSH TO REDESIGN Since taking charge, Coleman has sought to improve access to higher education by using the vast resources of the not-for-profit College Board, which had about $77 million in annual profit and $834 million in net assets in 2015. The College Board offers test-fee waivers to poor students as well as free test-preparation services through a partnership with Khan Academy, a not-for-profit educational organization. The redesign of the SAT, however, was Coleman’s most ambitious endeavor. The SAT and rival ACT are among the highest-stakes tests in American education, yardsticks used by colleges to choose among some 2 million applicants each year. To Coleman, the SAT needed to be more than a tool for universities to “do a good job of sorting people out,” said Jeff Dolven, a friend and college classmate who’s now a professor of poetry at Princeton University. “I think that Dave wants, in a sense, to change the world,” Dolven said. He sees the SAT as a means “to change the fortunes of students who deserve an education.” Coleman seemed aware of the challenges he faced. In 2012, the year he became College Board president, the ACT had just overtaken the SAT as the most popular college entrance exam in America. His problem wasn’t just a matter of students preferring the ACT over the SAT. Some universities were turning against standardized testing itself. A growing number have made the tests optional for applicants. One was Bennington College in Vermont, a liberal arts school that concluded test scores were an overrated indicator of future academic performance. Bennington chose to go “test optional” in 2006 - a decision made by Coleman’s own mother, Elizabeth, who served 25 years as the college’s president. “Probably it’s a good idea not to talk about this stuff,” Elizabeth Coleman said when contacted by Reuters. “I’m his mother. One of the wise things for a mother to do is to stay out of it.” A Rhodes Scholar with degrees from Yale, Oxford and Cambridge universities, David Coleman worked as a McKinsey & Co consultant. He went on to found an education technology company, which McGraw-Hill Education later acquired for millions of dollars, and started a nonprofit that developed the Common Core. Coleman had established himself as one of the most dynamic voices in education. But he had never managed anything as sprawling as the College Board, which pays him nearly $900,000 a year in salary and benefits and has about a dozen separate offices. “Going from an organization of approximately 22 people to one of 1,400 has been a little bit jarring,” Coleman said during a panel discussion at the Brookings Institution in November 2012, the month after he became College Board president. “To them or to you?” the moderator asked. An early sign of the difficulties that lay ahead came in February 2013, about a month after he sent around his plan for redesigning the SAT. That’s when Hal Higginbotham, a College Board senior vice president, delivered the new CEO a 14-page, footnoted memo. Coleman had called his manifesto a “beautiful vision” for redesigning the SAT. Higginbotham, who joined the organization while Coleman was still a teenager, titled his rejoinder “Towards a Meaningful and Successful Revision to the SAT.” In his memo, Higginbotham voiced support for Coleman’s overarching mission: creating an SAT that both predicts how well students will do in college (the test’s traditional role) and assesses their mastery of the Common Core. But he also schooled his new boss on the realities of building a standardized test. In the past, the College Board has needed about two years - and the help of outside contractors - just to develop new questions for an existing generation of the SAT. Coleman wanted the College Board to “create a new test from scratch” and handle most of the work itself, all in the same two-year time frame, Higginbotham wrote. “There is no reason (aside from eternal hope) to believe that a March 2015 date is achievable,” Higginbotham wrote, “and indeed there is every reason to conclude it is beyond the organization’s grasp.” Higginbotham proposed a 2017 launch for the new exam - two years later than Coleman wanted. Citing a non-disclosure agreement, Higginbotham declined to comment. He no longer works at the College Board. Other senior employees involved in a much simpler SAT redesign in 2005 also warned Coleman against moving too fast. One was the man in charge of research and development, Wayne Camara. Camara resigned in August 2013 to join the rival ACT after 19 years with the College Board. In his resignation letter, he told Coleman that the CEO’s “top-down prescription” for the redesign could jeopardize the validity of the exam. In the email introducing his vision memo, Coleman wrote that his ideas were “as always open to challenge, revision – and substantial improvement.” Camara’s resignation letter seems to dispute that. “I do not believe we had an opportunity to challenge or test many of these constraints or requirements before they were mandated,” Camara wrote of Coleman’s plans for the exam. “We also have no data to evaluate the new constructs, items or scores at this time.” Camara declined to comment on the resignation letter. PRESCIENT WARNINGS Coleman stuck to his release date. A PowerPoint presentation from that time refers to the new SAT launch as the “March 2015 imperative.” On August 18, 2013, less than two weeks after receiving Camara’s resignation, Coleman explained the urgency to College Board executives. Dozens of states were implementing the Common Core and were in the market for tests to evaluate student mastery of the new standards. The SAT, ACT and others were vying for that business. “The simple reason we must deliver the revised SAT by 2015 is that key states will make decisions about whether to adopt the ACT or another college ready measure in 2015,” he wrote. “If we are not part of that ecosystem, the reach of the SAT will be dramatically reduced.” By October 2013, however, an outside consultant was also questioning whether the College Board could meet Coleman’s deadline. The consultant, Gartner Inc, categorized the time frame as a “high risk” issue for the College Board. In the following weeks, senior College Board executives began discussing whether to delay the launch by a year, until March 2016. Amid the mounting difficulties, the College Board opted to postpone. Still, the timetable remained ambitious for a top-to-bottom redesign, and the warnings of Higginbotham, Camara and the consultant proved prophetic. As Reuters reported in September, the College Board released the exam even though the organization failed to meet its own design specifications for the test’s math section. It also failed to properly secure questions for the new test, leading to the breach earlier this year that has left 400 questions for upcoming SATs in limbo. In response to the breach, the College Board said it was taking "the test forms with stolen content off of the SAT administration schedule." But by withholding those questions, the organization depleted its already limited inventory of useable exams. As a result, it has fallen back on a practice that enables cheating: using previously administered versions of the test. Since the redesigned SAT was first given in March, the College Board already has recycled past versions of the new exam, both abroad and in the United States. As Reuters reported, that means a student could take the same version of the SAT twice, giving the test-taker a valuable advantage. After reading the story, a mother in Pennsylvania contacted Reuters to report that this happened to her son. He took the SAT in March and again in May. He knew he got a particular math problem wrong on the first test and researched how to answer it. To his surprise, she said, the May test repeated a number of reading and math questions used in March - including the one he had botched. He got it right the second time, and boosted his overall score on the SAT from 1280 to 1330 out of a possible 1600, she said. As part of his plan, Coleman wanted to enable students to take the new test online, not just on paper. Digitizing the SAT would cut administrative and scoring costs, he wrote in his vision memo. Before Coleman arrived, the College Board had been developing digital testing for more than two years, internal memos show. Offering tests online was complex, veterans warned Coleman. It would require extra research and logistical chores, such as arranging computers for exam-takers. Moreover, creating a digital SAT by March 2015 “is almost certainly not achievable,” Higginbotham wrote in his note to Coleman, “and definitely not in a responsible manner adhering to good measurement practice.” Coleman pressed on. In early 2013, he scuttled the College Board’s internal digital project and brought in an outsider to lead the effort: Mark Luetzelschwab, who had helped run an education technology company called Agilix. That July, Luetzelschwab touted how his former company would help execute the digital undertaking, documents show. Using Agilix software, the College Board would meet its goals “faster, cheaper, and (with) less risk than building” a digital platform internally, he wrote in an email to Jeremy Singer, Coleman’s new chief operating officer. Coleman’s team worked out a deal with Luetzelschwab’s old firm: a no-bid contract for as much as $30 million, documents show. Other top College Board officials protested. Three College Board technical specialists warned in detailed memos that Agilix lacked the expertise to deliver the technology it promised. Lawyers didn’t like the deal, either. General counsel Neil Lane urged Singer to abandon talks with Agilix; Lane viewed the large no-bid contract as a conflict of interest, according to emails. Another lawyer, John Newman, circulated a memo arguing that a contract with Agilix could be seen by the Internal Revenue Service as an illegal diversion of funds by creating a “private benefit” for Agilix. That, Newman believed, could jeopardize the organization’s tax-exempt status. Coleman stood firm. The College Board signed the deal in late 2013 and provided Agilix with a $3 million upfront payment, according to a document. Lane, who currently is a special counsel at the College Board, declined to comment. Newman no longer works for the College Board and declined to discuss his memo. Publicly, Coleman promised to roll out an online version of the test. Four months into the contract, however, Agilix had failed to deliver its first batch of work on the project, a document shows. By mid-April 2014, the College Board notified Agilix that it was in breach of contract. Agilix was fired months later. But it was allowed to keep the $3 million upfront payment, documents show. Curt Allen, the CEO of Agilix, declined to comment. Luetzelschwab, who was fired a few months later, declined to comment on his time at the College Board. The Agilix deal proved a setback. This July, ACT announced plans to roll out an online version of its test in 2017. Meanwhile, the College Board is again rebooting. In October, Coleman announced new hires to handle its digital efforts. NEW STANDARDS Coleman’s vision for the SAT prompted a broader worry that remains today. By so closely linking the exam to the Common Core, critics contend, the College Board has built an SAT that could discriminate against students whose states either have rejected or haven’t fully implemented the learning standards. Coleman himself was a central player in crafting Common Core, an initiative set up almost a decade ago by U.S. state governors and others. In 2008, Coleman’s Student Achievement Partners oversaw the development of the learning standards. By the end of 2013, 45 states and Washington D.C. adopted the Common Core. Three states later dropped out, though. They and other holdout states feared communities would lose too much control over what their kids get taught. The Core’s English Language Arts standards call on students to grapple with important readings, including hallowed U.S. documents such as the Declaration of Independence and works of American literature. Coleman’s redesigned SAT embraced the same concept. The Core’s reading standards “focus on students’ ability to read carefully and grasp information ... based on evidence in the text” - a pillar of the new SAT. And the Core’s math standards call for “greater focus on fewer topics” - another principle echoed in Coleman’s new SAT. Former College Board vice president Higginbotham was among the first to raise concerns about hitching the SAT’s future to the Common Core. In his February 2013 response to Coleman’s “beautiful vision,” Higginbotham noted that some states wouldn’t begin implementing the learning standards until the 2014-2015 school year, the same time period in which Coleman wanted to launch the redesigned SAT. It would take years for teachers and students to get fully up to speed on the new curriculum, he and others argued. “That circumstance leads me to wonder whether all students will have arrived at the starting line at the same time and whether the playing field for them will be level,” Higginbotham wrote in his memo to Coleman. Some students might be “more comfortable and competent than others in what will be presented” on a test aligned with the Common Core, he wrote. As a consequence, a Common Core-based SAT “will inadvertently favor students from those geographies that have made the most progress” with the standards, Higginbotham wrote. Such a situation “raises fundamental questions of fairness and equity.” “I sincerely wonder whether those test results will present the right basis for making decisions as to who will attend which college,” Higginbotham wrote. The eight states that haven’t fully embraced the Common Core, including Texas and Indiana, account for about 18 percent of the U.S. population. Despite the concerns, Coleman didn’t relent. The Common Core was being attacked from both left and right. Conservatives saw the standards as federal encroachment on state and local decision-making. Liberal critics said Common Core would require more standardized testing, which they opposed. In an August 2013 PowerPoint to the executive committee of the trustees, the College Board acknowledged that connecting the redesign to the Common Core was becoming a “risk.” “Don’t over-associate with Common Core,” the presentation said. “Don’t tie redesign explicitly to Common Core.” Some outside academics hired to review SAT questions for accuracy and fairness also worried about the Common Core link. They shared Higginbotham’s fear that the test would create a new group of disadvantaged students: test-takers from states that had rejected the Common Core or whose teachers weren’t ready to teach it. One concerned educator was Dan Lotesto, a lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He wrote of his concerns in an August 2014 letter to the College Board. Aligning the SAT with the Common Core standards is not “educationally sound, nor will it be fair to students for at least several years, even if all fifty states enthusiastically adopt them,” he wrote. Lotesto asked that the letter be shared with Coleman. It’s unclear whether it was. Another screener who voiced hesitation about aligning the test with the Common Core was Ann Davidian, a teacher from New York. Her views are recorded in the minutes of an April 2014 meeting of the committee that reviewed math questions for the redesigned SAT. Davidian said the College Board must “keep in mind (that) the Spring 2016 students have no Common Core background” in states such as hers. “Teachers haven’t taught this before and aren’t prepared,” she said, according to the minutes. Davidian declined to comment for this article. In a statement to Reuters, Coleman said College Board officials were mindful “that we needed to go beyond the Common Core to standards in places like Texas and Virginia to include what they found essential to college and career readiness.” The College Board also consulted with religious schools and parents who school their children at home “to make sure that no matter what set of standards they followed, their children had a fair shot on the exam.” It’s unclear how Trump’s election - and his choice of a Common Core opponent for secretary of education - might affect the SAT and the College Board. Coleman hasn’t spoken publicly about the president-elect’s views. But in September, at the conference for admissions officers and high school counselors, the CEO who had pushed the College Board to move quickly to redesign the SAT now was preaching patience. “I do seek a better future,” Coleman reassured the group. “But it’s going to take us time.” (Edited by Blake Morrison)