Supreme Court’s Colorado ballot decision exposes the lie behind conservatives’ claims of textualism

In overturning the Colorado Supreme Court’s disqualification of Donald Trump from the ballot, the Supreme Court conveniently ducked its responsibility and covered Section 3 of the 14th Amendment in about six feet of concrete. Knowing that Congress will do nothing before the election if ever, the court held that the Section wasn’t “self-executing”—Congress would have to set up rules.

It is important to note that the court majority could have stopped on the point the full bench agreed on unanimously—that a state can’t enforce this provision against federal candidates. They also wisely ignored Trump’s absurd claims that the president is not “an officer of the United States” and doesn’t take an oath to “support” the Constitution. But then, the Court majority simply tossed the whole thing into the lap of a divided Congress, ensuring it will never apply to Donald Trump. This wasn’t necessary and it was gratifying to see that four justices—Sotomayor, Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson—objected to that portion of the ruling.

On the self-executing issue, the unsigned majority “per curiam” decision is not merely evasion, but error. It rewrites Section 5 of the 14th Amendment. Where the section says that Congress may enact legislation to enforce the amendment, the court has transformed the language to say it must enact legislation. This avoids a simple command in the Constitution.

That command is categorical: It says that “[n]o person shall…hold any office…under the United States…who, having previously taken an oath…as an officer of the United States… shall have engaged in insurrection… against the same.” The clause could have easily included language tempering the disqualification with making the language effective “upon the adoption by Congress of procedures” or the like. But it does not.

The majority might console itself by saying it was reluctant to involve itself in a presidential election. Yet, by overturning the Colorado Supreme Court ruling disqualifying Trump from the ballot and leaving no route to consider it again before the next president takes office the Court did take sides—Donald Trump’s.

Yes, the justices seemed to know that the heaviest burden the court was carrying was its credibility. Starting with the narrow ground that the issue was a federal one, not a state one, was a good step. But the most credible thing to do was ignored by the majority: follow the “textualist” philosophy these justices claim as their unbending guide.

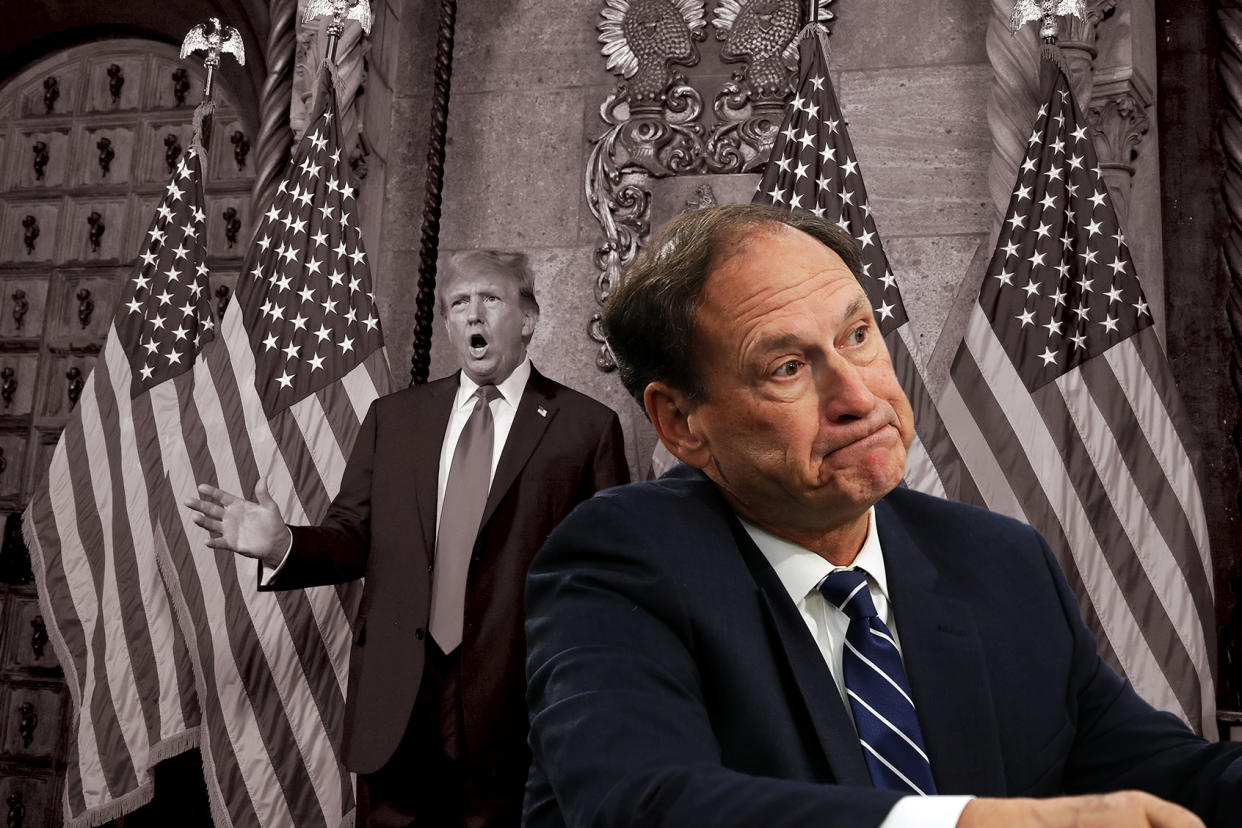

Put simply, textualists claim that judges should simply read the law and do what it says. Justice Alito emphasized in his 2022 majority opinion overturning the right to an abortion, that this means that the court cannot be affected by “how our political system or society will respond” to court rulings.

The court should have reverted to this first principle in the disqualification case. Pick up the Constitution, read it, and do what it says. If they did and believed that a president who engaged in insurrection is disqualified from the ballot, it would have had most of the job done. After all, a judge heard the case and determined that Trump did "engage in insurrection" on Jan. 6. And, interestingly, no member of the court put so much as a toe in that water. Apparently, no one on the court is willing to disagree with the lower court ruling that Trump engaged in an insurrection. It appears that the majority just doesn’t want anything to be done about it.

This means the court majority’s modesty is only skin deep. It suggests that, following Bush v. Gore, that the full court believes that it should take a modest approach to this matter and not use this extraordinary power themselves. This is at least understandable, if not legally correct. But the Court majority went further, favoring Trump and missing a chance to be modest without shielding Trump from accountability.

As two University of Virginia professors have argued, the 20th Amendment says that the question of disqualification should be judged after the election. The court could have adopted this view and additionally said that deciding whether the president-elect is disqualified is, without additional legislation, up to Congress. That would have been a modest approach that might have never required action from the court or Congress. After all, nothing would have to be done if the American people disqualify Trump themselves—by rejecting him at the ballot box.