The Supreme Court Can Repair Clarence Thomas’ Greatest Folly

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

In November the Supreme Court will take up United States v. Rahimi, a Texas case in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit ruled that the government may not disarm domestic abusers. Unless the Supreme Court reins in the 5th Circuit and restores some measure of rationality to its ever-expanding gun rights jurisprudence, the Second Amendment will now protect perpetrators of domestic violence.

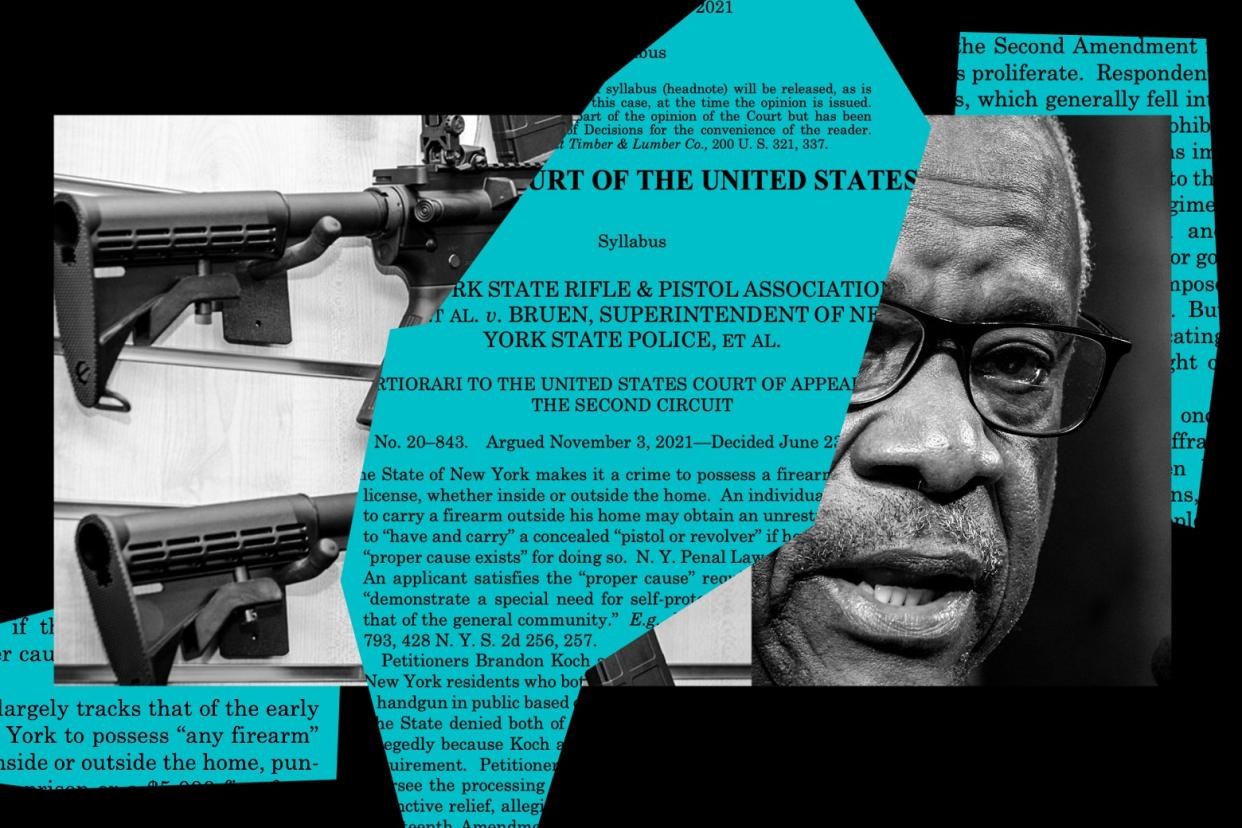

Rahimi is one of dozens of decisions decided since the Supreme Court struck down a century-old gun control law in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. The majority opinion in that case, authored by Justice Clarence Thomas, rejected the standard tools of constitutional analysis used by courts for the past century and instead substituted his own version of text, history, and tradition to determine the constitutionality of regulating firearms. Although Bruen invokes the authority of history, the version of the past it presents is almost unrecognizable to scholars familiar with the history of the founding period.

In Bruen, Thomas endorsed the questionable claim that the Second Amendment had been treated by lower courts as a “second-class” right. In reality, the Supreme Court has now bestowed on the Second Amendment a range of protections enjoyed by no other right in American law. Ironically, the current originalist version of the Second Amendment guiding the court is an invention of Thomas and has little connection to text, history, or tradition.

In Bruen, Thomas wrote that the Second Amendment issued “an unqualified command” that an individual’s right to purchase, possess, and carry firearms was to be protected in all but the narrowest circumstances. A genuine example of an unqualified command is a traffic stop sign. It is puzzling that anyone reading the text of the Second Amendment would conclude that it reads like a stop sign, but that is precisely what Thomas would have us believe: The Second Amendment bars virtually all modern laws that have tried to mitigate the ravages of gun violence. In support of his ahistorical assertion, Thomas did not cite any evidence from the founding era. (In fact, no provision of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, can accurately be described as an “unqualified command.”) No worries for Thomas. Instead, he merely offered a short footnote citing a celebrated modern First Amendment case, Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, which had nothing to do with guns or the Second Amendment. Citing the First Amendment’s protections of basic rights, including free speech and a free press, to support claims about the Second Amendment, a form of constitutional bait-and-switch, is a common tactic of gun rights advocates and their allies on the bench and in the legal academy. Thomas’ opinion, unconcerned with the inconvenient fact that guns and words have never been treated the same in American law, simply asserted that the two rights have been regulated in the same way over the long arc of American history.

Textual and historical support for treating the First and Second amendments alike, even conflating them, is in fact thin. The two amendments share little in common in terms of their language and structure. A close reading, in fact, reveals a crucial difference, which explodes Thomas’ conflation of the two. The First Amendment bars Congress from making any law “abridging the freedom of speech.” Founding-era dictionaries define abridging as a reduction or diminishment. The Second Amendment, however, states that the right to bear arms “shall not be infringed.” The same dictionaries make perfectly clear that infringed was not a synonym for abridged. Infringe meant “destroy or break.” So, while the First Amendment precludes regulation that even diminishes the rights that it protects, the Second Amendment bars destroying the right to bear arms, leaving open the possibility that the people, acting through their legislatures, could regulate that right to promote public safety and welfare. Every right mentioned in the Bill of Rights was subject to forms of regulation in the founding era, but the scope of regulation differed depending on the right. So, while the First Amendment precluded regulation that diminishes the rights it protects, the Second Amendment sets up a different metric.

Thomas’ intellectual sleight of hand, however, is easily exposed: The First Amendment case he cited to support his unqualified-command theory of the Second Amendment specifically contradicts his own approach. Rather than accept that the First Amendment is an unqualified command, Konigsberg concluded that courts ought to use the theory of interest balancing that Bruen expressly rejected.

In the months following Thomas’ opinion in Bruen, courts across the nation have struggled to implement his extremist originalist view of the Constitution. As Justice Stephen Breyer predicted in his withering dissent in Bruen, it was inevitable that courts would get history wrong. The cases decided in the wake of Bruen have vindicated his concerns—following Thomas to the letter, originalist judges have effectively weaponized their historical ignorance in the service of gun rights.

One lower court judge, following Bruen, erroneously claimed that the government could not require guns today to have serial numbers, noting that such a policy was not consistent with founding-era law. In fact, Gen. George Washington required muskets of the Continental Army to be stamped with an identifier to prevent them from being stolen, something closely analogous to the purpose of the modern law at issue in the case. Another judge reasoned that the absence of any evidence that the Founders enacted laws prohibiting guns in summer camp meant that New York was precluded from doing so today. The fact that modern-style summer camps did not exist when James Madison and the Congress wrote the Second Amendment did not seem to matter. Apparently, the judge did not ponder the absurdity of the notion that Americans living in an agrarian and predominantly rural society would have sent their kids to summer camp during an important part of the cycle of agricultural production. Second Amendment originalism in the post-Bruen period has become a parody of itself.

History fares no better in the 5th Circuit’s Rahimi decision. Rahimi is a classic example of what happens when individuals with little training in or understanding of history interpret 18th-century laws, substituting their own biases and anachronistic assumptions for real historical knowledge of early American law. One particularly problematic approach has led judges to treat silences in the historical record as evidence that regulation is not permissible. Setting aside the problems about gaps in the historical record, this approach ignores the fact that the Founders faced different types of gun-related problems and used methods of enforcement that are not easily researched in the standard sources consulted by courts.

Perhaps the most troubling feature of Thomas’ Bruen opinion is the notion that the Founders believed that limits of regulation were frozen in time as of 1791 and that subsequent generations lacked the authority to enact laws to deal with pressing social problems unanticipated by the Constitution’s framers. Thomas and the 5th Circuit’s extremist originalists appear to have forgotten the sage wisdom of James Madison, who reminded Americans, in his classic text The Federalist, that history is a source of wisdom but a flawed guide for a nation confronting new and unprecedented problems. Madison wrote that history’s guiding light was a beacon “which give warning of the course to be shunned, without pointing out that which ought to be pursued.”

The irony of Thomas’ cramped originalist vision is that it embodies a theory of legislative power that was itself rejected decisively by the Constitution’s supporters and foes in 1788. Nobody in 1791 or 1868, the years the Second and 14th amendments were enacted, respectively, believed that government was precluded from passing laws to regulate guns in order to promote public safety. Now Thomas’ radical version of originalism threatens to turn back the clock on protections for women and children because of a false history that ignores the founding generation’s most important contribution to American liberty: a Constitution flexible enough to adapt to the changing circumstances of the modern world.

If the Supreme Court evaluates Rahimi in the light of Bruen’s ahistorical approach to the past, it will compound its distortion of history and further erode public confidence in the court itself.

Despite a claim to be true to the text, Thomas has effectively rewritten the Second Amendment, positing an unqualified right that has no foundation in history, text, or tradition. The authors of the Second Amendment wisely chose not to copy the language used in the First Amendment for a reason. By prohibiting the destruction of the right to bear arms, not its regulation, the founding generation recognized that legislatures, not unelected judges, were better suited to fashioning policies to protect both the right to keep and bear arms and the equally important goal of public safety. Despite claims to the contrary, the Second Amendment does not prohibit the passage of sensible gun laws; its wording practically invites the people to do so. In contrast to Thomas, the founding generation correctly believed that without regulation, there was no liberty, only anarchy. But now reason itself, the very soul of the Founders’ enlightenment vision of law, seems to be in the crosshairs.