Teen was assaulted by Youth Villages staff, family and lawyer say, nonprofit denies claims

A 17-year-old girl was "body slammed" by two male counselors from Youth Villages after she refused to strip in front of them during an appointment at the Shelby County Health Department, the girl's mother said Wednesday afternoon. The teen was later brought back to the Youth Villages Bartlett campus and beaten by at least 12 counselors at that facility and would later die, her mother said.

"I sent her to Youth Villages to get help," the teen's mother, Shona Garner-White, said. "And now they're sending my baby back in a casket. Youth Villages is supposed to help my kid. I'm never supposed to bury my kid. My kid is supposed to bury me."

Youth Villages, in a statement, strongly denied that teen was beaten by 12 counselors and say that she was accompanied by two women to the health department.

That teenager, Alegend Jones, had spent the last two months in the care of Youth Villages after her mother asked the Department of Children's Services to take guardianship over Jones, though the mother would continue to have custody, to help with Jones' mental health struggles.

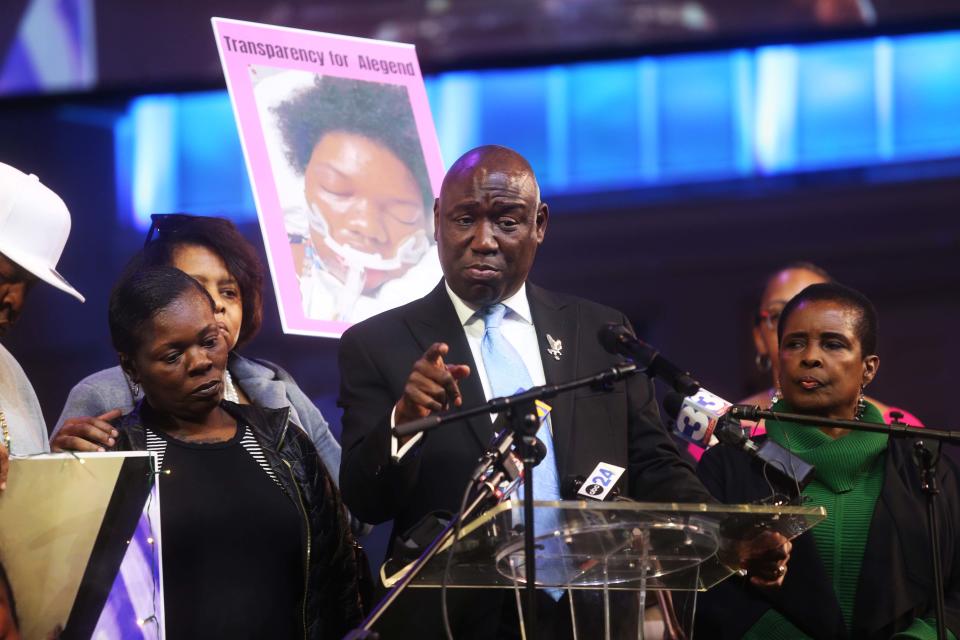

Garner-White retained notable civil rights attorney Ben Crump Tuesday, and he called a Wednesday afternoon press conference at Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church. Crump has now been retained by clients for six separate incidents in Shelby County.

Jones' death was first reported in mid November, in what Youth Villages described as an "incident" and "medical emergency" in a press release. In that release, Youth Villages said it did "not know the cause of the medical emergency" and denied that any abuses took place.

"Due to confidentiality laws involving children who receive mental and behavioral health care, we cannot discuss individual cases or health issues related to youth receiving help in our programs," Youth Villages said. "However, we can confirm that many of the statements and comments circulating on social media now are false. Specifically, there were no abusive or otherwise inappropriate interactions directed toward the young person."

Youth Villages is a nonprofit that opened its doors in Memphis to help "youth with the most severe mental, emotional and behavioral challenges" at its residential care centers.

"We are deeply saddened by this tragic event and loss of a child," Youth Villages said in its press release. "Our thoughts are with the family in this difficult time."

According to Crump, Jones was brought to the Shelby County Health Department for an appointment. The two male counselors who accompanied her from Youth Villages were in the room when Jones was told to strip. Crump said she refused, and the two men "body slammed" her.

Garner-White said Jones had been sexually assaulted as a child, and the trauma from that likely played into her refusal to take her clothes off in front of other men. That sexual assault was part of Jones' diagnosis for post-traumatic stress disorder, manic depression and bipolar disorder, her mother said.

Youth Villages, in a statement responding to Crump and Garner-Jones' allegations, said the two staff members that accompanied Jones to the health department were women.

Medical personnel, Crump added, called the police about the incident at the health department, and Jones was later taken back to a Youth Villages campus. When she got back, he said that was when counselors hit her again.

"It is alleged that over a dozen counselors at Youth Villages assaulted and battered this teenage child," Crump said Wednesday. "We don't know if there's video that captured the interactions between the counselors, who were supposed to be trained to deal with troubled youth, and the teenager — Shona's baby. But what we do know is whatever transpired ended up with the neurologists telling Shona that they believe the cause of death is that she died from a brain bleed."

Youth Villages, in that same response to the allegations, also strongly denied the allegation that there were 12 staff members who beat Jones, or took any abusive action towards her after the trip to the health department.

Garner-White said she has not spoken with anyone from Youth Villages since they told her Jones was dead.

"I reached out to Youth Villages to see if I can get my daughter's belongings. No answer," she said. "At least give me my baby's belongings. She has her daddy's necklace. Her daddy committed suicide, and Alegend took that very hard. I want to bury that in my daughter's casket. Just give me my baby's belongings, on top of the truth."

The Tennessee Department of Children's Services confirmed that they are engaged in an investigation into Jones' death.

"The Department of Children’s Services is saddened any time there is loss of life involving a youth," DCS said in an email statement. "We can confirm an investigation has commenced, and we are working alongside our law enforcement partners on this case."

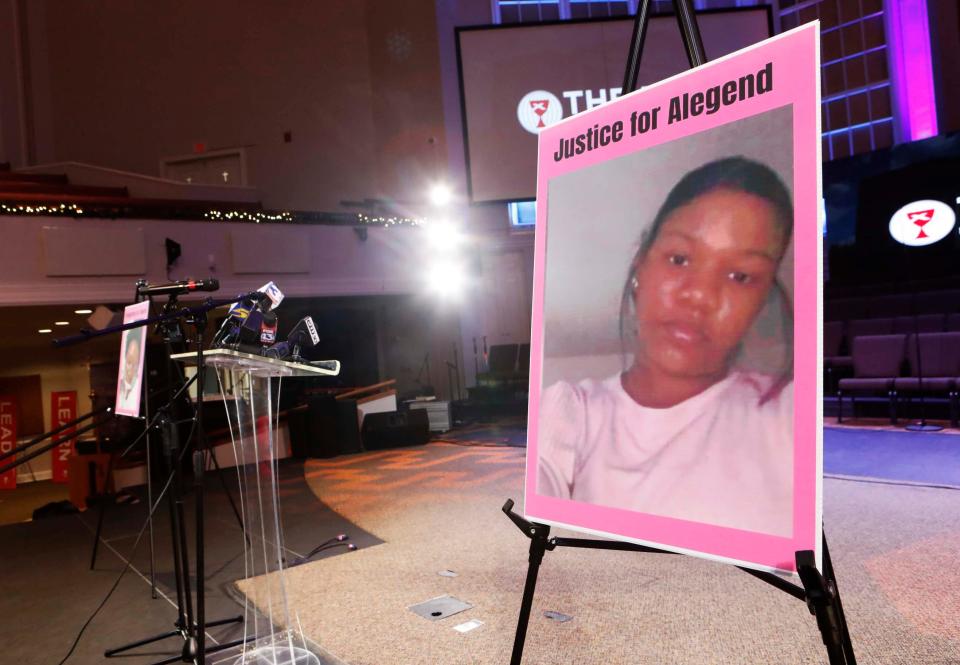

According to Garner-White, Jones had been at Youth Villages for just over two months when she died. Pictures that flanked the family and activists at the press conference Wednesday showed pictures of Jones prior to being hospitalized, and during her hospitalization. Jones' face appeared to be swollen, and she was intubated, in the hospital images.

Jones was placed on life support, but doctors proclaimed her as brain dead, and Garner-White had to "pull the plug" eventually.

"I said, 'What are y'all doing with her?' The doctor said, 'We are doing all the tests to make sure that there's no coming back from this, so when you pull that plug, nobody can say you jumped the gun,'" she said. "That's why she was on the ventilator for so long. I wasn't ready to pull the plug. But when I seen her brain coming out of her eyes, I said it's time for my baby to go. That's the type of death a mother should never have to go through."

Jones was born in Marion, Illinois, about two months early, Garner-White said. She would be released from the hospital after about two weeks of being on an incubator, during which Garner-White said her daughter "fought to live," and became a "vibrant" person.

Jones was Garner-White's sixth child out of 12, and she was "like the momma bear" with her siblings. She liked to dance. She liked music, especially NBA YoungBoy. Jones and Garner-White bonded over their shared love of food and eating.

In about 10 months, Garner-White said, Jones was slated to go into independent living and wanted to become a nurse.

"She was my child. She was my baby," Garner-White said. "At the end of the day, I don't care when people say she may have been a hellion. She was my hellion, and she deserved to give me grandkids. She deserved to go to nursing school and become what she wanted to when she got robbed of it."

Lucas Finton is a criminal justice reporter with The Commercial Appeal. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @LucasFinton.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Family says teen assaulted by Youth Villages staff, nonprofit denies claims