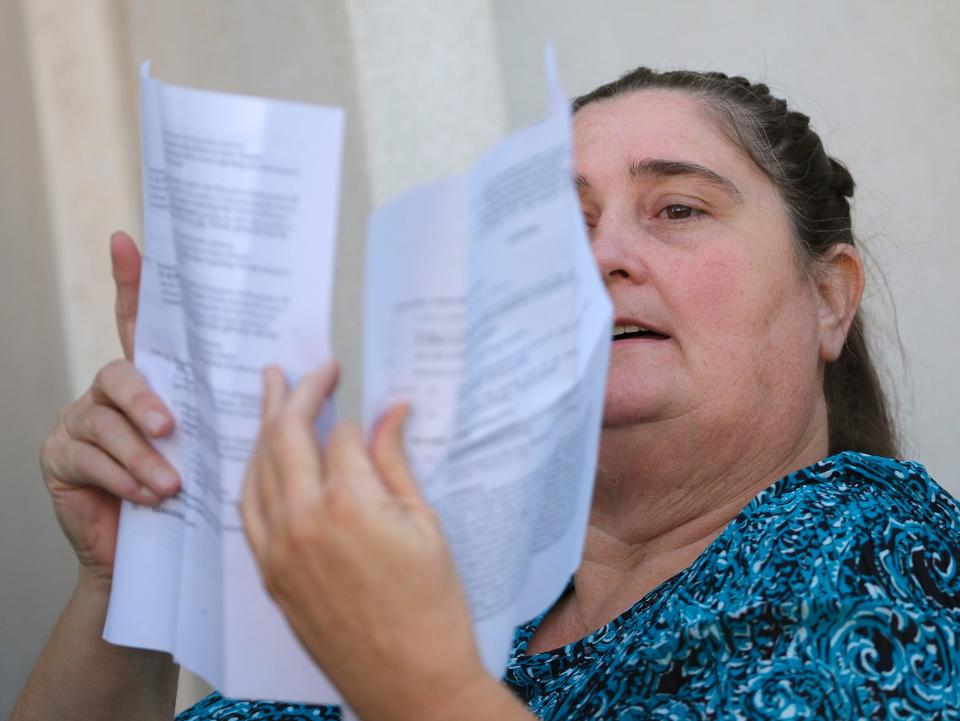

Ten years after Moore tornado killed her son, Danni Legg is still fighting for shelters in schools

MOORE — It’s said there are certain moments — and events — that define a person’s life. Weddings, promotions, ceremonies — each leave a mark and often spark a permanent change.

Danni Legg’s moment happened on May 20, 2013. That’s the day her son, Christopher, died.

Spring in Oklahoma brings rain, sun, flowers and on that particular day in May — twisters.

Early on the morning of May 20, a moderately strong cyclonic flow worked its way across the Southern Great Plains. There it collided with a cold air front from the Eastern Dakotas. By midday, the storm spawned twisters. Weather forecasters across the state went public with warnings. Early that afternoon, the National Weather Service issued tornado warnings for Grady County, western Cleveland County, northern McClain County and southern Oklahoma County.

The tornado hit Moore just as the school day was ending. The twister, later rated an EF5, one of the most rare and powerful, squatted along SW 119 and ripped apart homes and businesses. Then it attacked two schools — Plaza Towers Elementary and Briarwood Elementary. In the chaos, parents, frantic to try and get their kids, were stalled in traffic. At Briarwood, the kids were OK.

The story was different at Plaza Towers.

At Plaza Towers, the kids hunkered down, lining the halls. As the tornado shook the school, 9-year-old Christopher Legg covered his friend Megan, with his body. The walls fell.

Megan survived.

Christopher Legg and six other kids died.

“He was a hero,” his mother said, quietly. “He saved his friend.”

Many questions about tornado safety in schools, but few answers

For a while, her grief overwhelmed her. She couldn’t function. She already had planned two funerals that year — one for her mother, the other for her grandmother. The third funeral, her son’s, pushed her to the breaking point.

“I was just in survival mode,” she said. “That was it.”

Danni and her husband, Ross, had questions. She didn’t understand. Why did the school stay open when the storm warnings went out well in advance? Why shelter kids in the hall?

Why wasn’t there a storm shelter in the school?

She got few answers.

More: Moore honors 10-year anniversary of the deadly tornadoes that changed the town forever

At the same time, then-state Rep. Joe Dorman, a Democrat from Rush Springs, saw history repeating itself. Dorman is no stranger to tornadoes or the politics that seem to always follow them. He’d spent years waging a losing battle for better storm protection at mobile home parks. He advocated for better ways to protect Oklahomans from twisters. Dorman knew that in spite of Oklahoma's long history with volatile weather, no state law required storm shelters in public schools.

Losing elementary-age school kids, Dorman said, was more than he could stand. His first idea was to use a bill by then-state Rep. Ann Coody, a Republican from Lawton. Coody’s bill, which stalled in the Legislature, called for a $500 million bond issue to increase school security.

Dorman amended Coody’s bill and made his pitch. “I wanted to resurrect Ann’s bill, and instead, use the franchise tax (to underwrite the bonds),” he said. “There had been an effort to do away with the franchise tax. I said, instead of doing away with it, let’s use it for a direct benefit.”

But time was running out. It was late in the legislative session, and Dorman faced mounting opposition from House Speaker T.W. Shannon. “I was told it was too late,” he said. “We got pushback, and then leadership just flat out said this wasn’t going to happen.”

Not long after that Dorman met Danni Legg.

'People were empathetic at first'

Legg had come to the Capitol seeking commitments for new storm shelters. Initially, she was embraced because of her loss. Politicians of all stripes asked how they could help. They gave her business cards with a phone number and told her call.

They listened until she began talking about how much the shelters would cost.

“People were empathetic at first,” she said, “in the sense that a lot of people wanted to talk to me. But after the second week, it was different. I’m still at the Capitol, and I’m not going away. I want to know what their progress is. I’m asking them to give me something back. I was told ‘Well that takes money.’”

That legislative sympathy, she said, didn’t last very long. “I said, 'well, you have all these fundraisers you have all these donations coming in, take some of that money and do the right thing.'”

At the same time, there were lawsuits caused by the twister, complaints from school officials and arguments about state control of education. Few wanted to talk about the deaths of seven children. Fewer wanted to talk about money.

More: OU softball gave a girl an escape after the Moore tornado. Ten years later, their bond remains.

Danni Legg announced she supported Dorman’s bill, and the two of them kept pushing.

“The only way to do that is not sit back and complain and wait for somebody else to do something," she said. "You’ve got to step up and do it yourself. If you’re gonna wait for someone to do something for you or your family, you’re gonna be waiting for a very long time.”

After that, school officials stopped talking to Legg when she suggested spending less on football stadiums and more on kids’ safety. “I kept being told that it wasn't feasible in the state of Oklahoma," she said.

At that point, Danni Legg and Rep. Dorman tried Plan B. If the Legislature wouldn’t run a bond issue for storm shelters, the pair would use the initiative petition approach to get a $500 million bond for storm shelters.

“We filed an initiative petition under the Take Shelter Oklahoma,” Dorman said.

The plan was to reach out to public schools to get volunteers to help circulate the petition and for signatures.

“We wanted to collect signatures at Friday night football games,” he said. “Then Janet Barresi (state schools superintendent at the time) sent out notice to the schools that they were not allowed to participate using school time or on school property.”

Barresi’s opposition surprised Dorman.

Twister politics quickly derailed the petition drive, he said. Because they were prevented from collecting signatures at school events, the initiative’s supporters, despite their corps of volunteers, failed to get enough signatures to put the idea to a public vote.

For Dorman, the storm and the fight to protect school kids was the tipping point. Now in his final year as a state representative, Dorman launched a campaign for governor instead of a race for county commissioner as he had originally planned.

Danni Legg went a different direction; she became a one-woman crusade for school shelters.

“In the two years after Christopher’s death, I went to every school board meeting in the metro for two years after the tornado. Any time they had public comments, I was there,” she said.

A public vote that didn't happen, then a foundation

With no ballot initiative, Danni Legg pivoted a third time. She started a foundation in her son’s name. Instead of waiting for the schools to call, she went to them. She argued with superintendents and cajoled school board members. She talked to teachers and parents anyone who would listen.

Her foundation, A Hero’s Heart, partnered with Shelter in Place, a Utah business that specialized in storm shelters. The shelters — also ballistic proof — could be adapted to a school and built inside a classroom. The foundation raised money and leveraged a commitment by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to refund 75% of the cost back to the schools.

Danni Legg kept talking. This time, people listened.

Overcoming the opposition

The first shelters were built in Healdton, a small community northwest of Ardmore in 2014. There, Legg worked with Terry Shaw, the school’s superintendent, to put storm shelters inside elementary school classrooms. Shaw said the school installed seven shelters in the elementary school and two shelters in the junior high.

The shelters, which sit inside the classroom, resemble a space capsule. They are built from layered steel filled with materials such as Kevlar. Painted blue and white, the interiors have LED lighting, carpet and padded benches. The shelters have their own ventilation system and video monitors.

"The nice thing about these shelters is they are in the classroom," Shaw said. "If there's a storm, we can get our elementary kids in their shelter in less than a minute."

More: The Moore tornado destroyed the Orr Family Farm 10 years ago. How they endured, and rebuilt

In addition to being storm proof, Shaw said the shelters were also bulletproof in case of a school shooting incident. "We tested them using armor-piercing bullets, and we were safe," he said.

Not long after Healdton installed its shelters, school officials in the Atoka district did the same.

Today, Shaw doesn't worry as much about tornado season. Knowing he can protect the kids in his district, he said, gives him peace of mind. He's also thankful that Danni Legg keeps talking about storm shelters.

"She is a huge part of this," he said. "She's the reason the shelters are bulletproof."

Legg's A Hero's Heart foundation has built storm shelters in Oklahoma, California, Utah, Michigan, Texas and Arizona. Legg, herself, has traveled all over the country cornering politicians, business leaders, superintendents, teachers — anyone who will listen.

And, more often than not, a new shelter gets built.

“She is a force to be reckoned with,” Dorman said. “We need more people like her. She raised public awareness of the need of storm shelters. All too often, people think 'It won't happen to me.' She spoke against that."

Ten years later, she's still fighting

Ten years have passed. Danni Legg is still on the road, pushing school officials to build shelters and reminding them that the survivors of tornadoes need mental and physical health services. She tells people her story and urges parents and school officials to take steps to protect their kids. Over the past decade, she said she has visited every school district in Oklahoma.

She still watches the sky, too.

On those days when the weather turns ugly, Danni Legg gets nervous. She checks in with her family frequently. Big storms still cause her to pause and reach for the phone.

"I used to get really frightened," she said. "Now I check my weather app, and I'm on the phone in with my kids."

Her biggest fear is being able to reach her daughter at school in Sulphur. "When the weather turns bad, my first thought is about her. I call her and ask her what she needs. If I have to I drive through a storm, which I hate, I go."

She also remembers her son.

Even though it’s been a decade, Danni Legg carries Christopher's memory with her every day. She speaks of him reverently. Her voice softens, her eyes rim with tears.

"I miss him real bad. I didn't have time to get caught up in the grief," she said. "Pain is the aftermath of love. If you loved someone, you will always have the pain."

Her youngest daughter is about a year from graduation. Her oldest son in college. Soon the kids will be out of the house. There are more trips to make. More speaking engagements. She needs hip surgery. Still, she doesn’t plan to stop. The next spring might spawn a twister. The idea of another school shooting is always there.

And, she said, there are too many schools that still don’t have shelters. For better or worse, Danni Legg's life was altered permanently the day that twister struck. Still, it's a change she embraces.

“I can’t give up,” she said. “As soon as I do, something tragic may happen. That's not acceptable. I will be happy when every school in this state has storm shelters. I have to keep going. I don’t know what will happen to me if I slow down.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Mother of boy killed in Moore tornado fighting for storm shelters